-

Dark matter (DM) remains a major unsolved problem in modern cosmology. Astrophysical observations indicate that DM comprises more than 80% of the non-relativistic matter in the universe [1, 2]. Although numerous candidate models have been proposed to elucidate DM properties, the fundamental nature of DM remains unknown [3]. Particle DM candidates that interact weakly with ordinary matter, including weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs), WIMP-like particles, and sub-GeV particles, can annihilate or decay into standard model particles [4, 5]. These standard model particles can subsequently generate distinctive signatures, which can be probed using instruments such as radio telescopes, neutrino detectors, and cosmic-ray observatories [6−8]. As non-particle DM candidates, primordial black holes (PBHs) can generate standard model particles including photons, electron-positron pairs, and neutrinos via the process of Hawking radiation [9]. Consequently, this process may also produce observable signatures [10−16]. However, no such evidence has been found. These null detection results place stringent constraints on DM parameters (e.g., annihilation cross section, decay lifetime, and PBH mass and abundance), ruling out DM models incompatible with current observational data.

The 21 cm signal, particularly its power spectrum, provides a promising probe for DM [17−27]. Cosmic microwave background (CMB) observations place constraints on DM properties at recombination (

$ z\sim1100 $ ) [28−37], whereas cosmic rays and Lyman-α forest probe DM at low redshifts ($ z\leq6 $ ) [38−61]. However, these approaches are ineffective at probing DM during the cosmic dawn. As a sensitive probe of neutral hydrogen, the 21 cm power spectrum captures the imprints of DM during this epoch via DM's impact on the intergalactic medium (IGM), thereby bridging this observational gap. This occurs because DM particle annihilation, decay, and PBH Hawking radiation alter the thermal and ionization history of the IGM, thereby modifying the spin temperature of neutral hydrogen and affecting the brightness temperature of the 21 cm signal. The 21 cm power spectrum quantifies these brightness temperature fluctuations in three-dimensional space, thereby enabling the inference of DM properties.To date, no 21 cm power spectrum signal has been detected, whereas the next-generation radio telescopes are expected to probe this signal for the first time. Existing radio telescopes, including the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) [62, 63], Low Frequency Array (LOFAR) [64, 65], and Hydrogen Epoch of Reionization Array (HERA) [66], have thus far placed only upper limits on the 21 cm power spectrum. For example, MWA provided an upper limit of

$ (66.18\,{\rm{mK}})^2 $ at redshift$ z = 7.1 $ with scale$ k = 0.19\,\rm{h}\,{\rm{Mpc}}^{-1} $ at the 95% confidence level [62, 63], while HERA reported an upper limit on the 21 cm power spectrum of$ (30.76\,{\rm{mK}})^2 $ at the 95% confidence level at$ z = 7.9 $ with$ k = 0.19\,\rm{h}\,\rm {Mpc}^{-1} $ [66]. The strictest upper limit results from LOFAR, which is$ (68.66\,{\rm{mK}})^{2} $ at$ z= 10.1 $ with$ k = 0.076\,\rm{h}\,{\rm{Mpc}}^{-1} $ at the 95% confidence level [64, 65]. As the next-generation flagship radio telescope, the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), with its high spectral resolution and wide field of view, is expected to enable the first precise measurements of the 21 cm power spectrum. The SKA construction has made progress, and its precursor array, SKA-AA0.5, has successfully obtained its first scientific image [67]. When operational, the SKA will constrain DM annihilation, decay, and PBH Hawking radiation via their imprints on the 21 cm power spectrum, potentially providing unprecedented constraints on DM properties, thus offering new insights into its fundamental nature.In this work, we focus on the potential of the SKA to investigate DM. We first simulate the 21 cm power spectrum that incorporates the effects of DM particle annihilation, decay, and PBH Hawking radiation. We then utilize the Fisher information matrix to quantify the SKA's project sensitivity in constraining DM parameters. Finally, we propose and optimize observation strategies for the SKA to probe DM. This work is expected to provide new avenues for studying the nature of DM.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section II discusses the physical mechanisms of DM energy injection into the IGM. Section III shows the impact of energy injection on the 21 cm power spectrum. Section IV provides an introduction to the Fisher information matrix analysis. Section V quantifies the potential of the SKA for constraining the DM parameters. Section VI is the summary and discussion.

-

Dark matter (DM) remains a major unsolved problem in modern cosmology. Astrophysical observations evidence that DM comprises more than 80% of the non-relativistic matter in the universe [1, 2]. Although numerous candidate models have been proposed to elucidate DM properties, the fundamental nature of DM remains unknown [3]. Particle DM candidates that interact weakly with ordinary matter, including weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs), WIMP-like particles, and sub-GeV particles, can annihilate or decay into standard model particles [4, 5]. These standard model particles can subsequently generate distinctive signatures, which can be probed by instruments such as radio telescopes, neutrino detectors, and cosmic-ray observatories [6−8]. As non-particle DM candidates, primordial black holes (PBHs) can generate standard model particles including photons, electron-positron pairs, and neutrinos via the process of Hawking radiation [9]. Consequently, this process may also produce observable signatures [10−16]. However, no such evidence has been found. These null detection results place stringent constraints on DM parameters (e.g., annihilation cross section, decay lifetime, and PBH mass and abundance), ruling out DM models incompatible with current observational data.

The 21 cm signal, particularly its power spectrum, provides a promising probe for DM [17−27]. Cosmic microwave background (CMB) observations place constraints on DM properties at recombination (

$ z\sim1100 $ ) [28−37], while cosmic rays and Lyman-α forest probe DM at low redshifts ($ z\leq6 $ ) [38−61]. However, these approaches are ineffective at probing DM during the cosmic dawn. As a sensitive probe of neutral hydrogen, the 21 cm power spectrum captures the imprints of DM during this epoch via DM's impact on the intergalactic medium (IGM), thereby bridging this observational gap. This occurs because DM particle annihilation, decay, and PBH Hawking radiation alter the thermal and ionization history of the IGM, thereby modifying the spin temperature of neutral hydrogen and affecting the brightness temperature of the 21 cm signal. The 21 cm power spectrum quantifies these brightness temperature fluctuations in three-dimensional space, thereby enabling the inference of DM properties.To date, no 21 cm power spectrum signal has been detected, while the next-generation radio telescopes are expected to probe this signal for the first time. Existing radio telescopes, including the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) [62, 63], the the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR) [64, 65], and the the Hydrogen Epoch of Reionization Array (HERA) [66], have so far placed only upper limits on the 21 cm power spectrum. For example, MWA provided an upper limit of

$ (66.18\,{\rm{mK}})^2 $ at redshift$ z = 7.1 $ with scale$ k = 0.19\,h\,{\rm{Mpc}}^{-1} $ at the 95% confidence level [62, 63], while HERA reported an upper limit on the 21 cm power spectrum of$ (30.76\,{\rm{mK}})^2 $ at the 95% confidence level at$ z = 7.9 $ with$ k = 0.19\,h\,\rm {Mpc}^{-1} $ [66]. The strictest upper limit arises from LOFAR, which is$ (68.66\,{\rm{mK}})^{2} $ at$ z= 10.1 $ with$ k = 0.076\,h\,{\rm{Mpc}}^{-1} $ at the 95% confidence level [64, 65]. As the next-generation flagship radio telescope, the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), with its high spectral resolution and wide field of view, is expected to enable the first precise measurements of the 21 cm power spectrum. The SKA construction has made progress, and its precursor array, SKA-AA0.5, has successfully obtained its first scientific image [67]. When operational, the SKA will constrain DM annihilation, decay, and PBH Hawking radiation via their imprints on the 21 cm power spectrum, potentially providing unprecedented constraints on DM properties, thus offering new insights into its fundamental nature.In this work, we focus on the potential of the SKA to investigate DM. We first simulate the 21 cm power spectrum that incorporates the effects of DM particle annihilation, decay, and PBH Hawking radiation. We then utilize the Fisher information matrix to quantify the SKA's project sensitivity in constraining DM parameters. Finally, we propose and optimize observation strategies for the SKA to probe DM. This work is expected to provide new avenues for studying the nature of DM.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section II discusses the physical mechanisms of DM energy injection into IGM. Section III shows the impact of energy injection on the 21 cm power spectrum. Section IV provides an introduction to the Fisher information matrix analysis. Section V quantifies the potential of the SKA for constraining the DM parameters. Section VI is the summary and discussion.

-

In this section, we describe the scenarios of DM-induced exotic energy injected into the IGM. Throughout this work,

$ \rho_{{\rm{DM}}} $ encodes information on the distribution of DM, indicating$ \rho_{{\rm{DM}}}=\rho_{{\rm{DM}}}(z,{\bf{x}}) $ , with z and$ {\bf{x}} $ being the redshift and comoving position, respectively. -

In this section, we describe the scenarios of DM-induced exotic energy injected into IGM. Throughout this work,

$ \rho_{{\rm{DM}}} $ encodes information on the distribution of DM, indicating$ \rho_{{\rm{DM}}}=\rho_{{\rm{DM}}}(z,{\bf{x}}) $ with z and$ {\bf{x}} $ , respectively, being the redshift and the comoving position. -

The exotic energy can be injected into IGM due to the annihilation and decay of DM particles, denoted by χ. In this work, we consider the annihilation channels of

$ \chi\chi\rightarrow \gamma\gamma $ ,$ \chi\chi\rightarrow e^{+}e^{-} $ ,$ \chi\chi\rightarrow b\bar{b} $ , and the decay channels of$ \chi\rightarrow \gamma\gamma $ ,$ \chi\rightarrow e^{+}e^{-} $ ,$ \chi\rightarrow b\bar{b} $ . For a given channel, the primary particles can generate the secondary particles due to the hadronization process, which is simulated using$\mathrm{PYTHIA}$ [68] and$\mathrm{PPPC4DMID}$ [69]. In the following, we focus on photons and electron-positron pairs, which are either primary or secondary or both, since the exotic energy is deposited into the IGM primarily via them [70−73].In this work, we focus on the s-wave annihilation, which is characterized by zero relative orbital angular momentum, resulting in an approximately constant thermally-averaged annihilation cross-section. For this process, the energy injection rate per unit volume is given by

$ \left(\frac{{{\rm{d}}}E}{{{\rm{d}}}V{{\rm{d}}}t}\right)_{{\rm{inj}}} = f_{{\rm{ann}}}^{2} \rho^{2}_{{\rm{DM}}} c^2 \frac{\langle \sigma v \rangle}{m_{\chi}}\ , $

(1) where

$ f_{{\rm{ann}}} $ and$ m_{\chi} $ stand for the fraction and mass of DM particles that can annihilate,$ \rho_{{\rm{DM}}} $ the energy density of DM, c the speed of light, and$ \langle \sigma v \rangle $ the thermally averaged annihilation cross section for the given annihilation channel.For the decay of DM particles, we have the energy of photons and electron-positron pairs per unit volume per unit temporal interval as

$ \left(\frac{{{\rm{d}}}E}{{{\rm{d}}}V{{\rm{d}}}t}\right)_{{\rm{inj}}} =f_{{\rm{dec}}} \rho_{{\rm{DM}}} c^2 \frac{1}{\tau}\ , $

(2) where

$ f_{{\rm{dec}}} $ stands for the fraction of DM particles that can decay, and τ the lifetime of DM particles for the given decay channel.Throughout this work, we take

$ f_{{\rm{ann}}}=f_{{\rm{dec}}}=1 $ for simplicity, but can quickly recover them if necessary. -

The exotic energy can be injected into the IGM owing to the annihilation and decay of DM particles, denoted by χ. In this work, we consider the annihilation channels of

$ \chi\chi\rightarrow \gamma\gamma $ ,$ \chi\chi\rightarrow e^{+}e^{-} $ , and$ \chi\chi\rightarrow b\bar{b} $ and the decay channels of$ \chi\rightarrow \gamma\gamma $ ,$ \chi\rightarrow e^{+}e^{-} $ , and$ \chi\rightarrow b\bar{b} $ . For a given channel, the primary particles can generate the secondary particles owing to the hadronization process, which is simulated using$\mathrm{PYTHIA}$ [68] and$\mathrm{PPPC4DMID}$ [69]. In the following, we focus on photons and electron-positron pairs, which are either primary or secondary or both, since the exotic energy is deposited into the IGM primarily via them [70−73].In this work, we focus on the s-wave annihilation, which is characterized by zero relative orbital angular momentum, resulting in an approximately constant thermally averaged annihilation cross-section. For this process, the energy injection rate per unit volume is given by

$ \left(\frac{{{\rm{d}}}E}{{{\rm{d}}}V{{\rm{d}}}t}\right)_{{\rm{inj}}} = f_{{\rm{ann}}}^{2} \rho^{2}_{{\rm{DM}}} c^2 \frac{\langle \sigma v \rangle}{m_{\chi}}\ , $

(1) where

$ f_{{\rm{ann}}} $ and$ m_{\chi} $ are the fraction and mass of DM particles that can annihilate, respectively,$ \rho_{{\rm{DM}}} $ is the energy density of DM, c is the speed of light, and$ \langle \sigma v \rangle $ is the thermally averaged annihilation cross section for the given annihilation channel.For the decay of DM particles, we obtain the energy of photons and electron-positron pairs per unit volume per unit temporal interval as

$ \left(\frac{{{\rm{d}}}E}{{{\rm{d}}}V{{\rm{d}}}t}\right)_{{\rm{inj}}} =f_{{\rm{dec}}} \rho_{{\rm{DM}}} c^2 \frac{1}{\tau}\ , $

(2) where

$ f_{{\rm{dec}}} $ represents the fraction of DM particles that can decay, and τ is the lifetime of DM particles for the given decay channel.Throughout this work, we take

$ f_{{\rm{ann}}}=f_{{\rm{dec}}}=1 $ for simplicity but can quickly recover them if necessary. -

The exotic energy can also be injected into the IGM via the Hawking radiation of PBHs [9]. In this work, we focus on PBHs within the mass regime of

$ \sim10^{15}-10^{18} $ g. This mass range is of particular interest because PBHs within it can constitute a significant fraction of DM while evading existing constraints. PBHs in this mass range have not yet evaporated, and their Hawking radiation is potentially detectable, contributing to the exotic energy injection into the IGM. In this work, we consider the emission products in the form of photons and electron-positron pairs since the exotic energy is deposited into the IGM primarily via these particles [24−26].We express their energy per unit volume per unit temporal interval as

$ \begin{aligned}[b] \left(\frac{{{\rm{d}}}E}{{{\rm{d}}}V{{\rm{d}}}t}\right)_{{\rm{inj}}} =\;& \int_{0}^{5\,{{\rm{GeV}}}} \frac{{{\rm{d}}}^{2} N}{{{\rm{d}}} E {{\rm{d}}} t} \Big|_{{\rm{\gamma}}} n_{{\rm{PBH}}} E {{\rm{d}}} E \\ & + \int_{m_{{\rm{e}}}c^{2}}^{5\,{{\rm{GeV}}}} \frac{{{\rm{d}}}^{2} N}{{{\rm{d}}} E {{\rm{d}}} t}\Big|_{{\rm{e}}} n_{{\rm{PBH}}} (E - m_{{\rm{e}}} c^{2}) {{\rm{d}}} E\ , \end{aligned} $

(3) where

$ {{\rm{d}}}^2 N/({{\rm{d}}}E {{\rm{d}}}t) $ is the particle spectrum given by$\mathrm{BlackHawk}$ [74],$ m_{e} $ is the electron mass, and$ n_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ is the number density of PBHs. Here,$ n_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ is related to the PBH abundance, denoted by$ f_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ , as$ n_{{\rm{PBH}}} = \frac{f_{{\rm{PBH}}} \rho_{{\rm{DM}}} }{M_{{\rm{PBH}}}}\ , $

(4) where

$ M_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ denotes the PBH mass. Note that for simplicity, we have assumed a monochromatic mass function of PBHs, although the extended ones can be incorporated if necessary. -

The exotic energy can also be injected into the IGM via the Hawking radiation of PBHs [9]. In this work, we focus on PBHs within the mass regime of

$ \sim10^{15}-10^{18} $ g. This mass range is of particular interest because PBHs within it could constitute a significant fraction of DM while evading existing constraints. PBHs in this mass range have not yet evaporated, and their Hawking radiation is potentially detectable, contributing to the exotic energy injection into the IGM. In this work, we consider the emission products in the form of photons and electron-positron pairs, since the exotic energy is deposited into the IGM primarily via these particles [24−26].We have their energy per unit volume per unit temporal interval as

$ \begin{aligned}[b] \left(\frac{{{\rm{d}}}E}{{{\rm{d}}}V{{\rm{d}}}t}\right)_{{\rm{inj}}} =\;& \int_{0}^{5\,{{\rm{GeV}}}} \frac{{{\rm{d}}}^{2} N}{{{\rm{d}}} E {{\rm{d}}} t} \Big|_{{\rm{\gamma}}} n_{{\rm{PBH}}} E {{\rm{d}}} E \\ & + \int_{m_{{\rm{e}}}c^{2}}^{5\,{{\rm{GeV}}}} \frac{{{\rm{d}}}^{2} N}{{{\rm{d}}} E {{\rm{d}}} t}\Big|_{{\rm{e}}} n_{{\rm{PBH}}} (E - m_{{\rm{e}}} c^{2}) {{\rm{d}}} E\ , \end{aligned} $

(3) where

$ {{\rm{d}}}^2 N/({{\rm{d}}}E {{\rm{d}}}t) $ stands for the particle spectrum given by$\mathrm{BlackHawk}$ [74],$ m_{e} $ the electron mass, and$ n_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ the number density of PBHs. Here,$ n_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ is related to the PBH abundance, denoted by$ f_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ , as$ n_{{\rm{PBH}}} = \frac{f_{{\rm{PBH}}} \rho_{{\rm{DM}}} }{M_{{\rm{PBH}}}}\ , $

(4) where

$ M_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ stands for the PBH mass. It should be noted that for simplicity we have assumed a monochromatic mass function of PBHs, though the extended ones can be incorporated if necessary. -

In this section, following the conventions of Refs. [75−77], we demonstrate imprints of the injected exotic energy on the 21 cm brightness-temperature fluctuations at the cosmic dawn. We simulate the 21 cm signal using a modified version of

$\mathrm{21cmFAST}$ [78]. In this work, we modify the equations within$\mathrm{21cmFAST}$ for the gas temperature$ T_{{\rm{K}}} $ , ionization fraction$ x_{{\rm{e}}} $ , and Lyman-α coupling efficiency$ x_{\alpha} $ to incorporate the effects of exotic energy injection from DM. The modifications, detailed in Section ⅢB, account for the heating, ionization, and Lyman-α flux induced by exotic injection. We employ the$\mathrm{darkhistory}$ code [70] to compute the coefficiencies for exotic energy deposition through heating, ionization, and Lyman-α scattering, namely$ F_{{\rm{heat}}} $ ,$ F_{{\rm{HI}}} $ ,$ F_{{\rm{He}}} $ , and$ F_{{\rm{exc}}} $ , as described in Section III.B. -

In this section, following the conventions of Refs. [75−77], we demonstrate imprints of the injected exotic energy on the 21 cm brightness-temperature fluctuations at cosmic dawn. We simulate the 21 cm signal using a modified version of

$\mathrm{21cmFAST}$ [78]. In this work, we modify the equations within$\mathrm{21cmFAST}$ for the gas temperature$ T_{{\rm{K}}} $ , the ionization fraction$ x_{{\rm{e}}} $ , and the Lyman-α coupling efficiency$ x_{\alpha} $ to incorporate the effects of exotic energy injection from DM. The modifications, detailed in Section ⅢB, account for the heating, ionization, and Lyman-α flux induced by exotic injection. We employ the$\mathrm{darkhistory}$ code [70] to compute the coefficiencies for exotic energy deposition through heating, ionization, and Lyman-α scattering, namely$ F_{{\rm{heat}}} $ ,$ F_{{\rm{HI}}} $ ,$ F_{{\rm{He}}} $ , and$ F_{{\rm{exc}}} $ , as described in Section ⅢB. -

The differential brightness temperature of the 21 cm signal evaluated at the observer is defined by

$ \begin{aligned}[b] {\delta T_{b}}(\nu,{\bf{x}}) \simeq\;& 23\, x_{{\rm{HI}}}(z,{\bf{x}}) \left(\frac{0.15}{\Omega_{{\rm{m}}}}\right)^{\frac{1}{2}} \left(\frac{\Omega_{{\rm{b}}} h^{2}}{0.02}\right) \left(\frac{1+z}{10}\right)^{\frac{1}{2}} \\ & \times \left[1-\frac{T_{{\rm{CMB}}}(z)}{T_{{\rm{S}}}(z,{\bf{x}})}\right]\; {\rm{mK}}\ , \end{aligned} $

(5) where

$ \nu=\nu_{21}/(1+z) $ is the redshifted frequency of 21 cm photons,$ x_{{\rm{HI}}} $ is the neutral fraction of hydrogen,$ T_{{\rm{CMB}}} $ is the temperature of the CMB,$ T_{{\rm{S}}} $ is the spin temperature of neutral hydrogen,$ \Omega_{{\rm{m}}} $ (or$ \Omega_{{\rm{b}}} $ ) is the present-day energy-density fraction of non-relativistic (or baryonic) matter, and h is the dimensionless Hubble constant. Here,$ T_{{\rm{S}}} $ is explicitly given by$ T_{{\rm{S}}}^{-1} = \frac{T_{{\rm{CMB}}}^{-1} + x_{\alpha}T_{\alpha}^{-1} + x_{{\rm{c}}}T_{{\rm{K}}}^{-1}}{1 + x_{\alpha} + x_{{\rm{c}}}}\ , $

(6) where

$ T_{\alpha} $ is the color temperature of Lyman-α photons,$ T_{{\rm{K}}} $ is the kinetic temperature of the IGM gas,$ x_{\alpha} $ is the Lyman-α coupling coefficient, and$ x_{{\rm{c}}} $ is the collisional coupling coefficient. Owing to resonant scattering,$ T_{\alpha} $ is tightly coupled to$ T_{{\rm{K}}} $ , namely$ T_{\alpha}\simeq T_{{\rm{K}}} $ .The observable is defined as follows. We first define the fractional perturbation to the differential 21 cm brightness temperature as

$ \delta_{21}(\nu,{\bf{x}}) = \frac{\delta T_{b}(\nu,{\bf{x}})}{\overline{\delta T_{b}}(\nu)} - 1 \ , $

(7) where

$ \overline{\delta T_{b}} $ is the spatial average of$ \delta T_{b} $ . We further define the dimensionless power spectrum for$ \delta_{21} $ as$ \langle \tilde{\delta}_{21}(z,{\bf{k}}) \tilde{\delta}_{21}^{\ast}(z,{\bf{k}}') \rangle = (2\pi)^{3}\delta({\bf{k}}-{\bf{k}}')\frac{2\pi^{2}}{k^{3}}\Delta_{21}^{2}(z,k)\ , $

(8) where

$ \tilde{\delta}_{21}(z,{\bf{k}}) $ is the Fourier mode of$ \delta_{21}(\nu,{\bf{x}}) $ , with ν being replaced with$ z=\nu_{21}/\nu-1 $ and$ {\bf{k}} $ (or k) being the comoving wavevector (or wavenumber),$ \langle... \rangle $ is the ensemble average, and$ \delta({\bf{k}}-{\bf{k}}') $ is the Dirac delta function. Following the conventions of Ref. [75], we define the 21 cm power spectrum in units of temperature as$ \overline{\delta T_{b}}^{2}(z)\Delta_{{\rm{21}}}^{2}(z,k) $ , in which we have replaced ν with z once again. In the following, the above observable will be frequently referred to. -

The differential brightness temperature of the 21 cm signal evaluated at the observer is defined by

$ \begin{aligned}[b] {\delta T_{b}}(\nu,{\bf{x}}) \simeq\;& 23\, x_{{\rm{HI}}}(z,{\bf{x}}) \left(\frac{0.15}{\Omega_{{\rm{m}}}}\right)^{\frac{1}{2}} \left(\frac{\Omega_{{\rm{b}}} h^{2}}{0.02}\right) \left(\frac{1+z}{10}\right)^{\frac{1}{2}} \\ & \times \left[1-\frac{T_{{\rm{CMB}}}(z)}{T_{{\rm{S}}}(z,{\bf{x}})}\right]\; {\rm{mK}}\ , \end{aligned} $

(5) where

$ \nu=\nu_{21}/(1+z) $ is the redshifted frequency of 21 cm photons,$ x_{{\rm{HI}}} $ the neutral fraction of hydrogen,$ T_{{\rm{CMB}}} $ the temperature of the CMB,$ T_{{\rm{S}}} $ the spin temperature of neutral hydrogen,$ \Omega_{{\rm{m}}} $ (or$ \Omega_{{\rm{b}}} $ ) the present-day energy-density fraction of non-relativistic (or baryonic) matter, and h the dimensionless Hubble constant. Here,$ T_{{\rm{S}}} $ is explicitly given by$ T_{{\rm{S}}}^{-1} = \frac{T_{{\rm{CMB}}}^{-1} + x_{\alpha}T_{\alpha}^{-1} + x_{{\rm{c}}}T_{{\rm{K}}}^{-1}}{1 + x_{\alpha} + x_{{\rm{c}}}}\ , $

(6) where

$ T_{\alpha} $ stands for the color temperature of Lyman-α photons,$ T_{{\rm{K}}} $ the kinetic temperature of the IGM gas,$ x_{\alpha} $ the Lyman-α coupling coefficient, and$ x_{{\rm{c}}} $ the collisional coupling coefficient. Due to resonant scattering,$ T_{\alpha} $ is tightly coupled to$ T_{{\rm{K}}} $ , namely$ T_{\alpha}\simeq T_{{\rm{K}}} $ .The observable is defined as follows. We first define the fractional perturbation to the differential 21 cm brightness temperature as

$ \delta_{21}(\nu,{\bf{x}}) = \frac{\delta T_{b}(\nu,{\bf{x}})}{\overline{\delta T_{b}}(\nu)} - 1 \ , $

(7) where

$ \overline{\delta T_{b}} $ stands for the spatial average of$ \delta T_{b} $ . We further define the dimensionless power spectrum for$ \delta_{21} $ as$ \langle \tilde{\delta}_{21}(z,{\bf{k}}) \tilde{\delta}_{21}^{\ast}(z,{\bf{k}}') \rangle = (2\pi)^{3}\delta({\bf{k}}-{\bf{k}}')\frac{2\pi^{2}}{k^{3}}\Delta_{21}^{2}(z,k)\ , $

(8) where

$ \tilde{\delta}_{21}(z,{\bf{k}}) $ is the Fourier mode of$ \delta_{21}(\nu,{\bf{x}}) $ with ν being replaced with$ z=\nu_{21}/\nu-1 $ and$ {\bf{k}} $ (or k) being the comoving wavevector (or wavenumber),$ \langle... \rangle $ the ensemble average, and$ \delta({\bf{k}}-{\bf{k}}') $ the Dirac delta function. Following the conventions of Ref. [75], we define the 21 cm power spectrum in units of temperature as$ \overline{\delta T_{b}}^{2}(z)\Delta_{{\rm{21}}}^{2}(z,k) $ , in which we have replaced ν with z once again. In the following, the above observable would be frequently referred to. -

Once injected into IGM, the exotic energy can be deposited into IGM, thus altering the thermal and ionization histories of IGM. It can also contribute to the Lyman-α flux, altering the Lyman-α coupling coefficient. Therefore, we expect the injected exotic energy to leave imprints on the 21 cm power spectrum.

Due to energy deposition processes, the exotic energy can heat and ionize the IGM gas. The heating and ionizing rates per baryon, respectively, are given by

$ \epsilon_{{\rm{exo,{\rm{heat}}}}} = F_{{\rm{heat}}}(z) \frac{1}{n_{{\rm{b}}}} \left(\frac{{{\rm{d}}} E}{{{\rm{d}}} V {{\rm{d}}} t}\right)_{{\rm{inj}}}\ , $

(9) $ \begin{aligned}[b] \Lambda_{{\rm{exo,{\rm{ion}}}}} =\;& F_{{\rm{HI}}}(z) \frac{1}{n_{{\rm{b}}}} \frac{n_{{\rm{H}}}}{n_{{\rm{b}}}} \frac{1}{E^{{\rm{HI}}}_{{\rm{ion}}}} \left(\frac{{{\rm{d}}} E}{{{\rm{d}}} V {{\rm{d}}} t}\right)_{{\rm{inj}}} \\&+ F_{{\rm{He}}}(z) \frac{1}{n_{{\rm{b}}}} \frac{n_{{\rm{He}}}}{n_{{\rm{b}}}} \frac{1}{E^{{\rm{He}}}_{{\rm{ion}}}} \left(\frac{{{\rm{d}}} E}{{{\rm{d}}} V {{\rm{d}}} t}\right)_{{\rm{inj}}}\ . \end{aligned} $

(10) Here, we adopt the delayed energy deposition model that is integrated in

$\mathrm{Darkhistory}$ .$ F_{{\rm{heat}}} $ ,$ F_{{\rm{HI}}} $ , and$ F_{{\rm{He}}} $ represent the energy deposition efficiencies via the processes of IGM heating, hydrogen ionization, and helium ionization, respectively. These deposition efficientcies are estimated by the$\mathrm{darkhistory}$ .$ n_{{\rm{b}}} $ ,$ n_{{\rm{H}}} $ , and$ n_{{\rm{He}}} $ denote the number densities of baryons, hydrogen, and helium, respectively.$ E^{{\rm{HI}}}_{{\rm{ion}}} $ and$ E^{{\rm{He}}}_{{\rm{ion}}} $ are the ionization energies of hydrogen and helium, respectively.Considering both astrophysical processes and exotic energy, we have the heating and ionizing equations of the IGM gas as

$ \begin{aligned}[b] \frac{{{\rm{d}}} T_{{\rm{K}}}(z,{\bf{x}})}{{{\rm{d}}} z} =\;&\frac{2}{3 k_{{\rm{B}}} (1+x_{{\rm{e}}})} \frac{{{\rm{d}}} t}{{{\rm{d}}} z} (\epsilon_{{\rm{exo,{\rm{heat}}}}}+\epsilon_{{\rm{X,{\rm{heat}}}}}+\epsilon_{{\rm{IC,{\rm{heat}}}}}) \\ &+ \frac{2 T_{{\rm{K}}}}{3 n_{{\rm{b}}}} \frac{{{\rm{d}}} n_{{\rm{b}}}}{{{\rm{d}}} z} - \frac{T_{{\rm{K}}}}{1 + x_{{\rm{e}}}} \frac{{{\rm{d}}} x_{{\rm{e}}}}{{{\rm{d}}} z}\ , \end{aligned} $

(11) $ \frac{{{\rm{d}}} x_{{\rm{e}}}(z,{\bf{x}})}{{{\rm{d}}} z} = \frac{{{\rm{d}}} t}{{{\rm{d}}} z} (\Lambda_{{\rm{exo,{\rm{ion}}}}} + \Lambda_{{\rm{X,{\rm{ion}}}}} - \alpha_{{\rm{A}}} C x^{2}_{{\rm{e}}} n_{{\rm{H}}})\ . $

(12) Here,

$ T_{{\rm{K}}} $ and$ x_{{\rm{e}}}=1-x_{{\rm{HI}}} $ , respectively, represent the kinetic temperature and ionization fraction.$ k_{{\rm{B}}} $ is the Boltzmann constant. t is the cosmic time.$ \epsilon_{{\rm{X,{\rm{heat}}}}} $ and$ \epsilon_{{\rm{IC,{\rm{heat}}}}} $ , respectively, stand for the heating rates per baryon due to astrophysical X-rays and inverse-Compton scattering.$ \Lambda_{{\rm{X,{\rm{ion}}}}} $ is the ionization rate due to astrophysical X-rays.$ \alpha_{{\rm{A}}} $ denotes the case-A recombination coefficient. C is the clumping factor. We have modified the corresponding equations in$\mathrm{21cmFAST}$ .Due to the deposition, the exotic energy can also have a contribution to the Lyman-α flux, i.e.,

$ J_{\alpha,{{\rm{exo}}}} = F_{{\rm{exc}}}(z) \frac{1}{n_{{\rm{b}}}} \frac{c n_{{\rm{b}}}}{4 \pi} \frac{1}{E_{\alpha}} \frac{1}{H(z) \nu_{\alpha}}\left(\frac{{{\rm{d}}} E}{{{\rm{d}}} V {{\rm{d}}} t}\right)_{{\rm{inj}}}\ . $

(13) Here,

$ F_{{\rm{exc}}} $ represents the energy deposition efficiency via the process of hydrogen excitation. It is also given by$\mathrm{darkhistory}$ .$ E_{\alpha} $ and$ \nu_{\alpha} $ , respectively, denote the energy and frequency of Lyman-α photons.$ H(z) $ is the Hubble parameter at z.Taking into account Eq. (13), we modify the Lyman-α coupling coefficient to

$ x_{\alpha} = \frac{1.7 \times 10^{11}}{1 + z} S_{\alpha} (J_{\alpha,{{\rm{exo}}}} + J_{\alpha,{{\rm{X}}}} + J_{\alpha,\rm \star})\ . $

(14) Here,

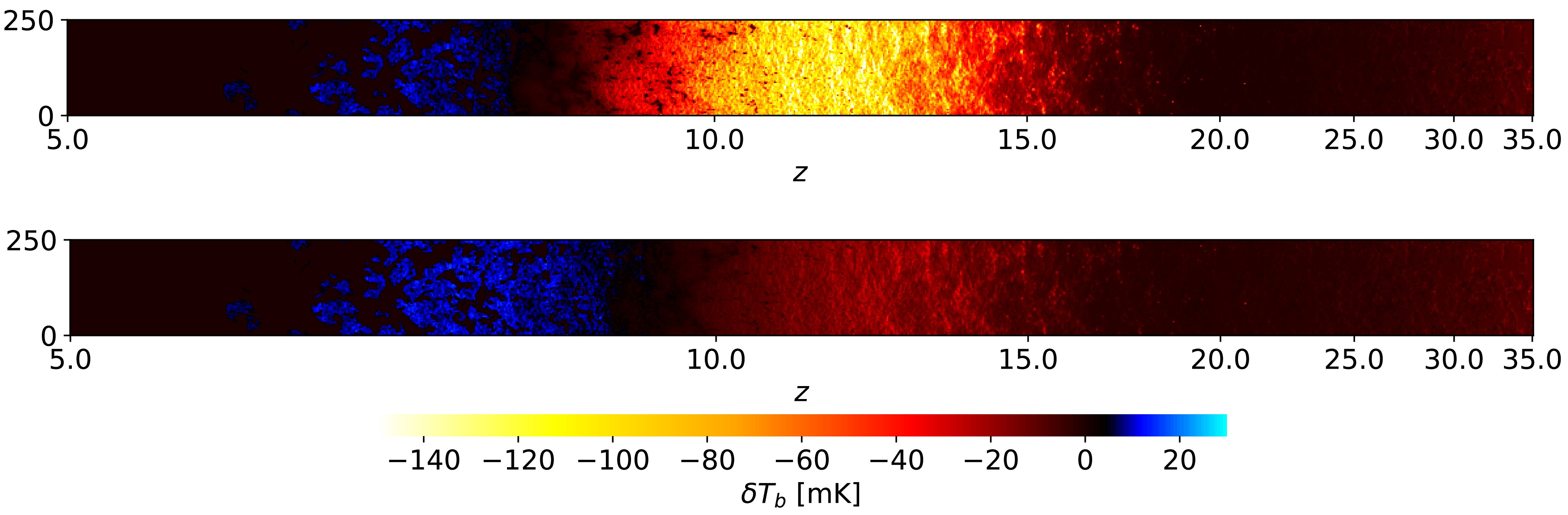

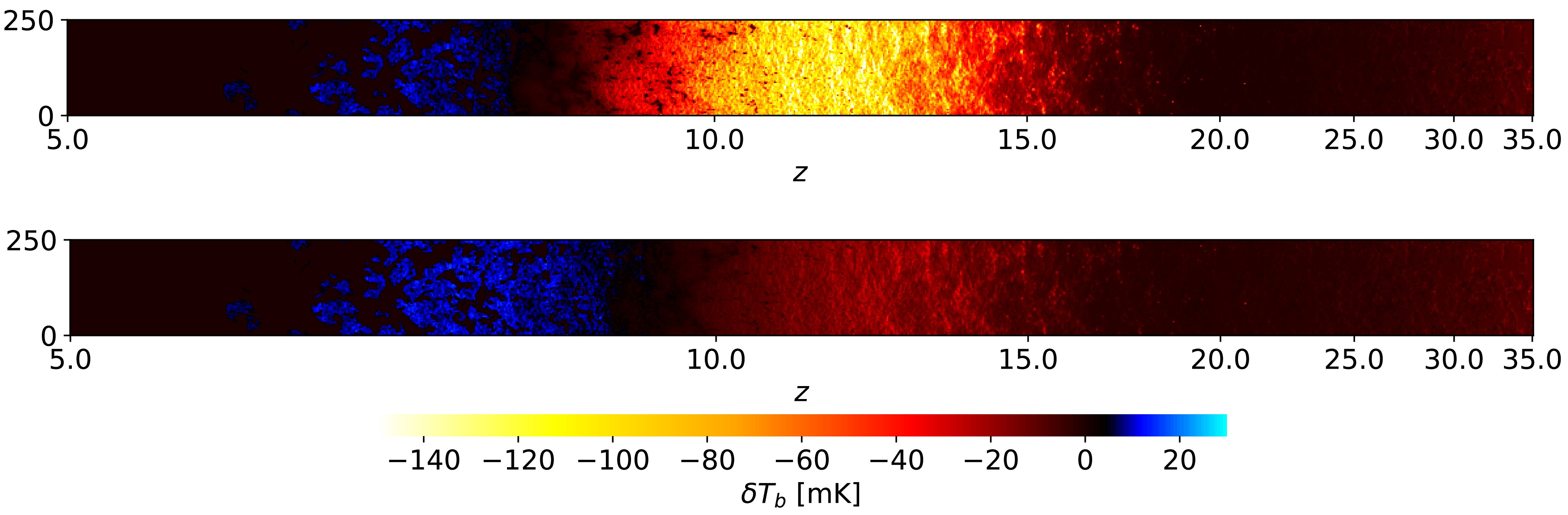

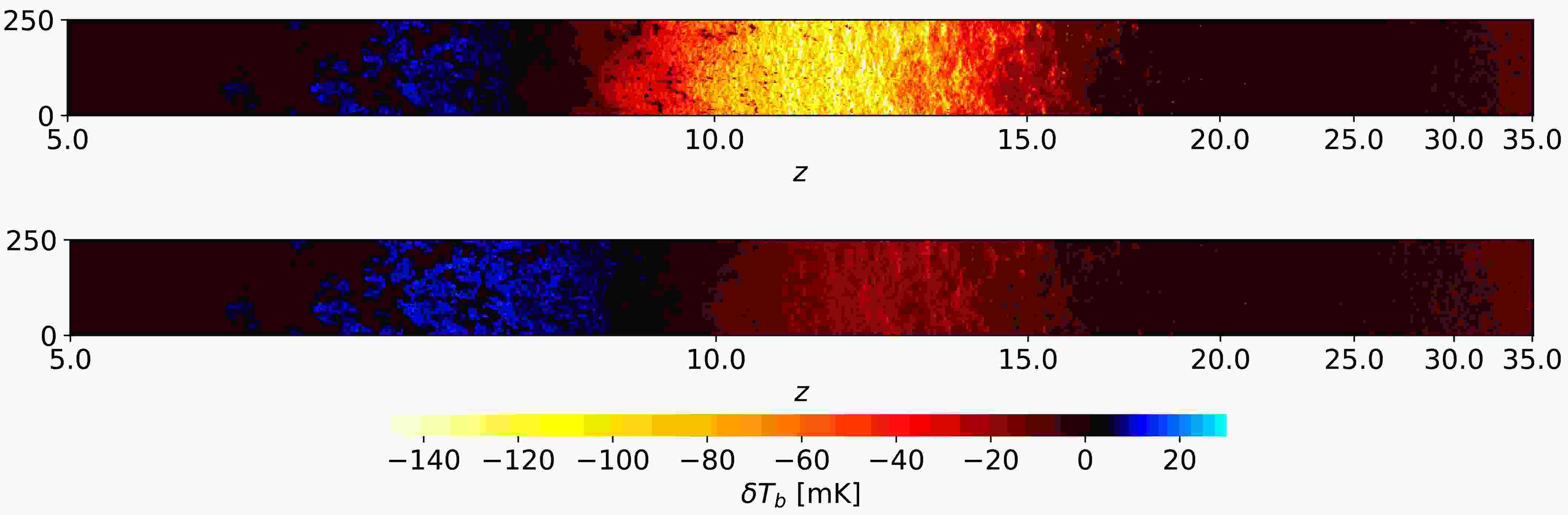

$ S_{\alpha} $ denotes a quantum-mechanical correction factor.$ J_{\alpha,{{\rm{X}}}} $ and$ J_{\alpha,\rm \star} $ , respectively, stand for the Lyman-α fluxes contributed by astrophysical X-rays and stellar emissions. We have also modified the corresponding equations in$\mathrm{21cmFAST}$ . In Fig. 1, we show the lightcone slices of our fiducial model and of a model with DM particle decay for comparison.

Figure 1. (color online) Lightcone slices of the differential brightness temperature in our

$ (250\; {{\rm{Mpc}}})^{3} $ large simulation box. The fiducial model are shown on the upper panel. The bottom panel show the slice with DM particle annihilation through$ \chi\rightarrow e^{+}e^{-} $ channel with$ m_{\chi} = 10 \; {\rm{GeV}} $ and$ \tau = 10^{27}\, s $ . -

When injected into the IGM, the exotic energy can be deposited into the IGM, thus altering its thermal and ionization histories. It can also contribute to the Lyman-α flux, altering the Lyman-α coupling coefficient. Therefore, we expect the injected exotic energy to leave imprints on the 21 cm power spectrum.

Because of energy deposition processes, the exotic energy can heat and ionize the IGM gas. The heating and ionizing rates per baryon, respectively, are given by

$ \epsilon_{{\rm{exo,{\rm{heat}}}}} = F_{{\rm{heat}}}(z) \frac{1}{n_{{\rm{b}}}} \left(\frac{{{\rm{d}}} E}{{{\rm{d}}} V {{\rm{d}}} t}\right)_{{\rm{inj}}}\ , $

(9) $ \begin{aligned}[b] \Lambda_{{\rm{exo,{\rm{ion}}}}} =\;& F_{{\rm{HI}}}(z) \frac{1}{n_{{\rm{b}}}} \frac{n_{{\rm{H}}}}{n_{{\rm{b}}}} \frac{1}{E^{{\rm{HI}}}_{{\rm{ion}}}} \left(\frac{{{\rm{d}}} E}{{{\rm{d}}} V {{\rm{d}}} t}\right)_{{\rm{inj}}} \\&+ F_{{\rm{He}}}(z) \frac{1}{n_{{\rm{b}}}} \frac{n_{{\rm{He}}}}{n_{{\rm{b}}}} \frac{1}{E^{{\rm{He}}}_{{\rm{ion}}}} \left(\frac{{{\rm{d}}} E}{{{\rm{d}}} V {{\rm{d}}} t}\right)_{{\rm{inj}}}\ . \end{aligned} $

(10) Here, we adopt the delayed energy deposition model that is integrated in

$\mathrm{Darkhistory}$ .$ F_{{\rm{heat}}} $ ,$ F_{{\rm{HI}}} $ , and$ F_{{\rm{He}}} $ represent the energy deposition efficiencies via the processes of IGM heating, hydrogen ionization, and helium ionization, respectively. These deposition efficientcies are estimated using$\mathrm{darkhistory}$ .$ n_{{\rm{b}}} $ ,$ n_{{\rm{H}}} $ , and$ n_{{\rm{He}}} $ denote the number densities of baryons, hydrogen, and helium, respectively.$ E^{{\rm{HI}}}_{{\rm{ion}}} $ and$ E^{{\rm{He}}}_{{\rm{ion}}} $ are the ionization energies of hydrogen and helium, respectively.Considering both astrophysical processes and exotic energy, we obtain the heating and ionizing equations of the IGM gas as

$ \begin{aligned}[b] \frac{{{\rm{d}}} T_{{\rm{K}}}(z,{\bf{x}})}{{{\rm{d}}} z} =\;&\frac{2}{3 k_{{\rm{B}}} (1+x_{{\rm{e}}})} \frac{{{\rm{d}}} t}{{{\rm{d}}} z} (\epsilon_{{\rm{exo,{\rm{heat}}}}}+\epsilon_{{\rm{X,{\rm{heat}}}}}+\epsilon_{{\rm{IC,{\rm{heat}}}}}) \\ &+ \frac{2 T_{{\rm{K}}}}{3 n_{{\rm{b}}}} \frac{{{\rm{d}}} n_{{\rm{b}}}}{{{\rm{d}}} z} - \frac{T_{{\rm{K}}}}{1 + x_{{\rm{e}}}} \frac{{{\rm{d}}} x_{{\rm{e}}}}{{{\rm{d}}} z}\ , \end{aligned} $

(11) $ \frac{{{\rm{d}}} x_{{\rm{e}}}(z,{\bf{x}})}{{{\rm{d}}} z} = \frac{{{\rm{d}}} t}{{{\rm{d}}} z} (\Lambda_{{\rm{exo,{\rm{ion}}}}} + \Lambda_{{\rm{X,{\rm{ion}}}}} - \alpha_{{\rm{A}}} C x^{2}_{{\rm{e}}} n_{{\rm{H}}})\ . $

(12) Here,

$ T_{{\rm{K}}} $ and$ x_{{\rm{e}}}=1-x_{{\rm{HI}}} $ represent the kinetic temperature and ionization fraction, respectively.$ k_{{\rm{B}}} $ is the Boltzmann constant. t is the cosmic time.$ \epsilon_{{\rm{X,{\rm{heat}}}}} $ and$ \epsilon_{{\rm{IC,{\rm{heat}}}}} $ are the heating rates per baryon due to astrophysical X-rays and inverse-Compton scattering, respectively.$ \Lambda_{{\rm{X,{\rm{ion}}}}} $ is the ionization rate due to astrophysical X-rays.$ \alpha_{{\rm{A}}} $ denotes the case-A recombination coefficient. C is the clumping factor. We have modified the corresponding equations in$\mathrm{21cmFAST}$ .Owing to the deposition, the exotic energy can also contribute to the Lyman-α flux, i.e.,

$ J_{\alpha,{{\rm{exo}}}} = F_{{\rm{exc}}}(z) \frac{1}{n_{{\rm{b}}}} \frac{c n_{{\rm{b}}}}{4 \pi} \frac{1}{E_{\alpha}} \frac{1}{H(z) \nu_{\alpha}}\left(\frac{{{\rm{d}}} E}{{{\rm{d}}} V {{\rm{d}}} t}\right)_{{\rm{inj}}}\ . $

(13) Here,

$ F_{{\rm{exc}}} $ represents the energy deposition efficiency via hydrogen excitation. It is also given by$\mathrm{darkhistory}$ .$ E_{\alpha} $ and$ \nu_{\alpha} $ denote the energy and frequency of Lyman-α photons, respectively.$ H(z) $ is the Hubble parameter at z.Considering Eq. (13), we modify the Lyman-α coupling coefficient to

$ x_{\alpha} = \frac{1.7 \times 10^{11}}{1 + z} S_{\alpha} (J_{\alpha,{{\rm{exo}}}} + J_{\alpha,{{\rm{X}}}} + J_{\alpha,\rm \star})\ . $

(14) Here,

$ S_{\alpha} $ denotes a quantum-mechanical correction factor.$ J_{\alpha,{{\rm{X}}}} $ and$ J_{\alpha,\rm \star} $ are the Lyman-α fluxes contributed by astrophysical X-rays and stellar emissions, respectively. We have also modified the corresponding equations in$\mathrm{21cmFAST}$ . In Fig. 1, we show the lightcone slices of our fiducial model and of a model with DM particle decay for comparison.

Figure 1. (color online) Lightcone slices of the differential brightness temperature in our

$ (250\; {{\rm{Mpc}}})^{3} $ large simulation box. The fiducial model is shown on the upper panel. The bottom panel shows the slice with DM particle decay through$ \chi\rightarrow e^{+}e^{-} $ channel with$ m_{\chi} = 10 \; {\rm{GeV}} $ and$ \tau = 10^{27}\, {\rm s}$ . -

To quantify the sensitivity of the SKA in probing DM particles and PBHs, we employ the Fisher information matrix. Assuming Gaussian posterior distributions for relevant parameters, the Fisher matrix for the 21 cm power spectrum is given by [75]

$ \begin{aligned}[b] F_{ij} =\;& \sum_{l}^{N_z}\sum_{m}^{N_k} \frac{1}{\sigma_{{\rm{tot}}}^2(z_{l},k_{m})}\frac{\partial [\overline{\delta T_{b}}^{2}(z_{l})\Delta_{21}^2(z_{l},k_{m} )]} {\partial \theta_i} \\&\times \frac{\partial [\overline{\delta T_{b}}^{2} (z_{l})\Delta_{21}^2(z_{l},k_{m} )]} {\partial \theta_j}\ . \end{aligned} $

(15) In this work, we discretize the 21 cm power spectrum into

$ N_k \times N_z $ independent bins, following Ref. [79].$ N_k $ and$ N_z $ represent the numbers of linearly discretized bins in k and z, respectively. The k range is from 0.2 to 0.9$ {{\rm{Mpc}}}^{-1} $ , and the z range is from 6 to 20.$ \sigma_{{\rm{tot}}}^2(z_{l},k_{m}) $ is the total noise for the 21 cm power spectrum in the redshift bin$ z_{l} $ and wavenumber bin$ k_{m} $ .$ \theta_{i} $ and$ \theta_{j} $ represent the i-th and j-th parameter in the parameter set.The total noise on the 21 cm power spectrum measurement arises from three key sources [80]

$ \sigma_{{\rm{tot}}}^2 \equiv \left[0.2 \overline{\delta T_{b}}^{2}\Delta_{21}^2\right]^2 + \sigma_{{\rm{poisson}}}^2 + \sigma_{{\rm{ins}}}^{2}\ , $

(16) where the first term represents a conservative 20% theoretical uncertainty in modeling the 21 cm signal [81], the second term quantifies the cosmic variance due to finite simulation volume, and the third term denotes instrumental noise dominated by the system temperature [80]. The instrumental noise is related to the square of system temperature, i.e.,

$ \sigma_{{\rm{ins}}} \propto T_{{\rm{sys}}}^{2} $ , while the system temperature can be estimated by [80]$ T_{{\rm{sys}}}(\nu) = 16.3 \times 10^6 \, {{\rm{K}}} \left(\frac{\nu}{2\, {{\rm{MHz}}}}\right)^{-2.53} \ . $

(17) In this work, we adopt this system temperature in package

$\mathrm{21cmSense}$ [80] to estimate the instrumental noise of SKA. We adopt stations in the central area of the SKA1-low (an array of 295 stations, where the diameter of each station is 35 m, distributed across a circular area with a diameter of$ 1.7 $ km), observing with a total bandwidth of$ 8\,{{\rm{MHz}}} $ and spectral resolution of$ 100\,{{\rm{kHz}}} $ , and a total integration time of 10,000 hours [82]. Marginalized uncertainty for a specific parameter$ \theta_{i} $ satisfies$ \sigma_{\theta_{i}} \geq \sqrt{(F^{-1})_{ii}} $ [83]. This suggests that the Fisher matrix provides conservative lower bounds on parameter constraints. The$ 1\sigma $ uncertainty of the parameter$ \theta_{i} $ is its standard deviation. Furthermore, the correlation between parameters$ \theta_{i} $ and$ \theta_{j} $ is quantified by the dimensionless correlation coefficient$ R_{ij} = C_{ij}/\sqrt{ C_{ii} C_{jj} } $ , where the covariance matrix$ C_{ij} $ is the inverse of the Fisher matrix$ F_{ij} $ .Our model incorporates two categories of independent parameters, which are astrophysical parameters and parameters for DM particles and PBHs. Astrophysical parameters follow the conventions of

$\mathrm{21cmFAST}$ , including$ t_{\star} $ ,$ a_{\star} $ ,$ a_{{\rm{esc}}} $ ,$ {{\rm{log}}}_{10}f_{\star} $ ,$ {{\rm{log}}}_{10}f_{{\rm{esc}}} $ , and$ {{\rm{log}}}_{10}L_{{\rm{X}}} $ , where$ t_{\star} $ is the dimensionless star formation timescale,$ a_{\star} $ represents the power-law index of stellar-to-halo mass ratio,$ a_{{\rm{esc}}} $ represents the power-law index of UV photon escape fraction,$ {{\rm{log}}}_{10}f_{\star} $ represents the stellar-to-halo mass ratio,$ {{\rm{log}}}_{10}f_{{\rm{esc}}} $ represents the UV escape fraction, and$ {{\rm{log}}}_{10}L_{{\rm{X}}} $ represents X-ray luminosity per star formation rate in unit of$ {{\rm{erg}}} \cdot yr \cdot sec^{-1} M^{-1}_{\odot} $ , where$ M_{\odot} $ stands for the solar mass. The remaining parameters correspond to DM physics.$ \langle \sigma v \rangle $ characterizes the annihilation cross section of DM particles, in units of$ {{\rm{cm}}}^{3}\; s^{-1} $ .$ \Gamma = \tau^{-1} $ represents the decay rate of DM particles, in units of$ {{\rm{s}}}^{-1} $ .$ f_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ signifies the abundance of PBHs. For the fiducial model in Fig. 2, the astrophysical parameters are set to$ t_{\star} = 0.5 $ ,$ a_{\star} = 0.5 $ ,$ a_{{\rm{esc}}} = -0.5 $ ,$ {{\rm{log}}}_{10}f_{\star} = -1.3 $ ,$ {{\rm{log}}}_{10}f_{{\rm{esc}}} = -1.0 $ , and$ {{\rm{log}}}_{10}L_{{\rm{X}}} = 40.0 $ , while the DM and PBH parameters,$ \langle \sigma v \rangle $ , Γ, and$ f_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ are set to zero.

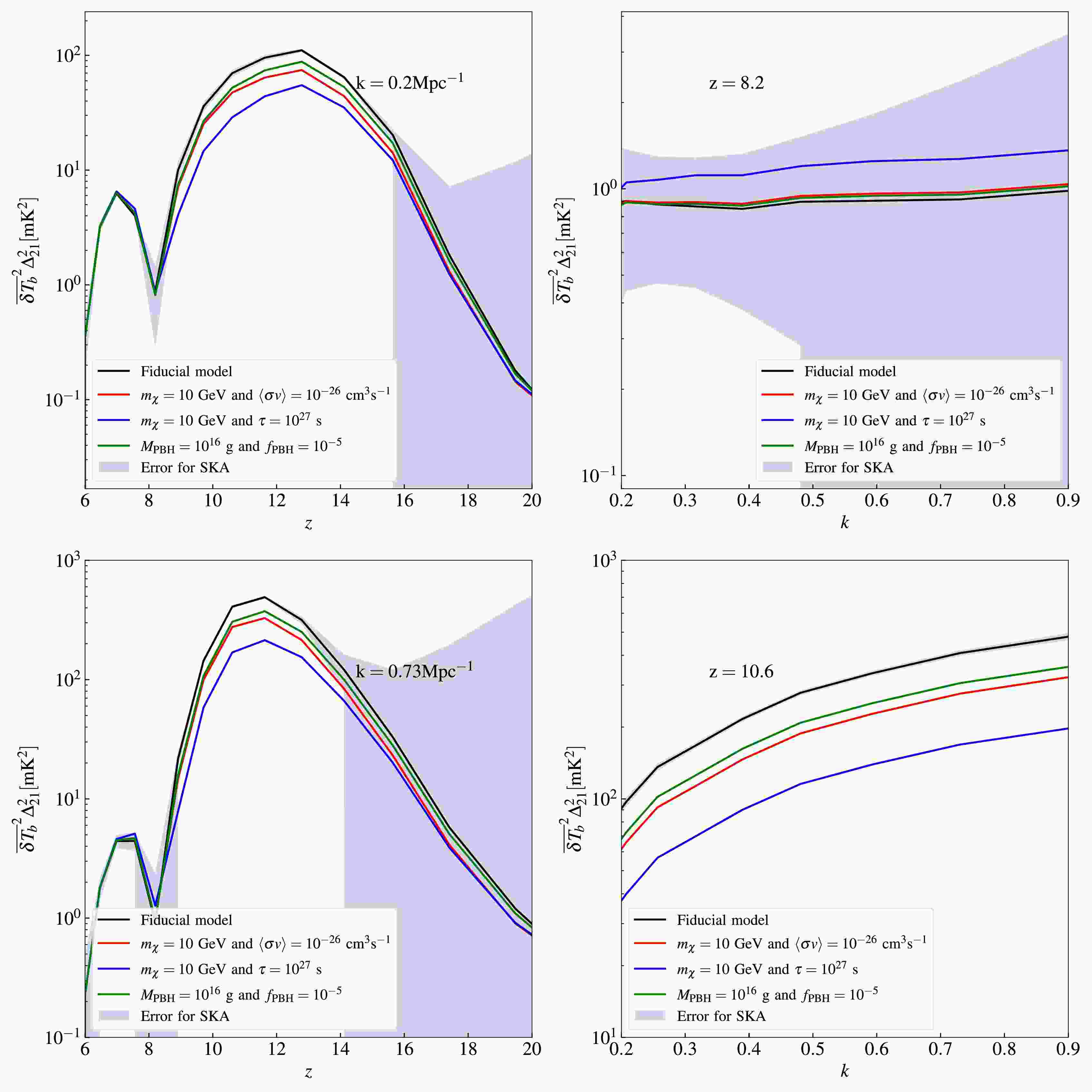

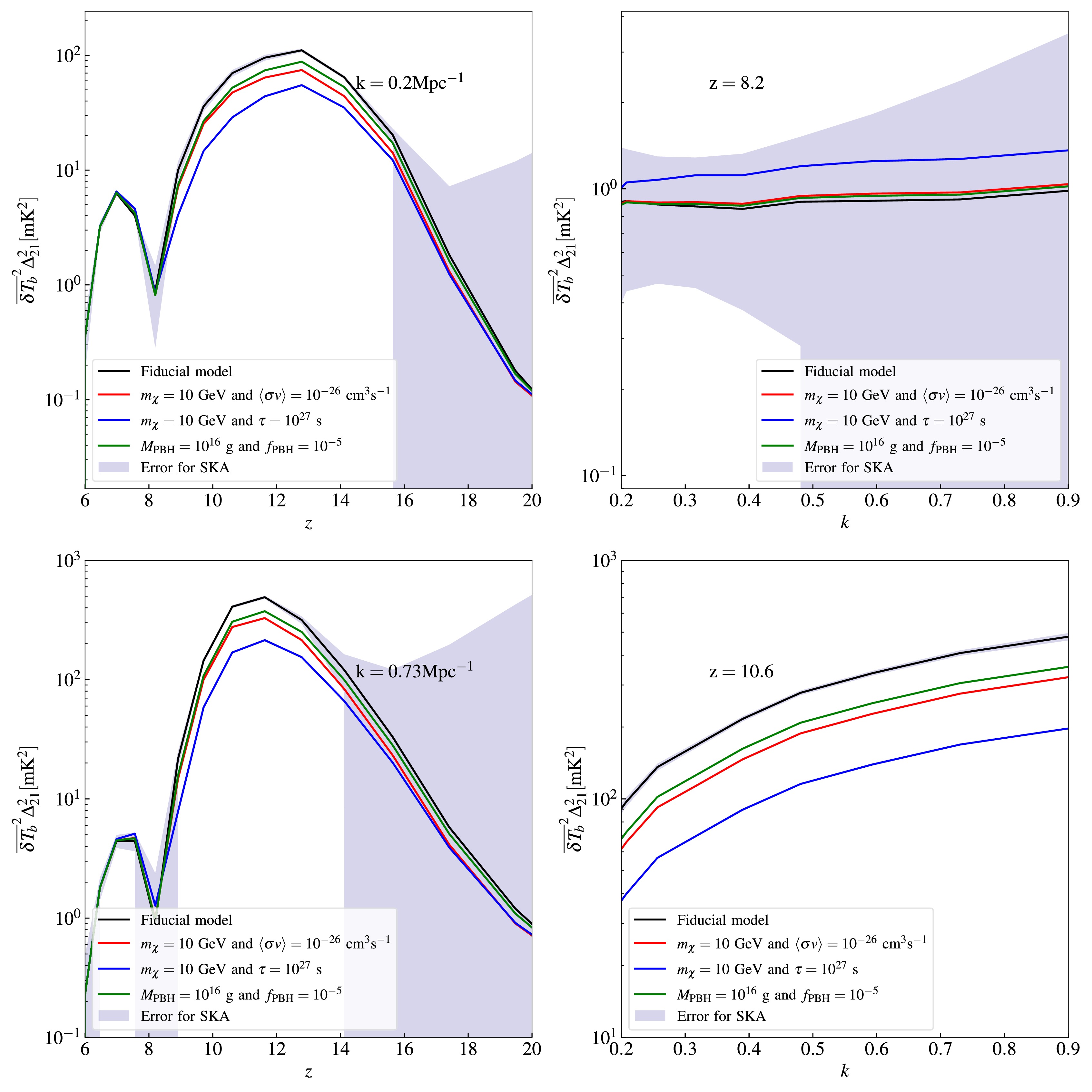

Figure 2. (color online) The 21 cm power spectrum under different energy injection scenarios. Left panels: The 21 cm power spectrum as a function of redshift z at fixed scales

$ k = 0.2 \,{{\rm{Mpc}}}^{-1} $ and$ k = 0.73\,{{\rm{Mpc}}}^{-1} $ . Right panels: The 21 cm power spectrum as a function of the scale at redshift$ z = 8.2 $ and$ z = 10.6 $ . In each panel, the instrumental noise is shown by the shaded region. Black curves show the 21 cm power spectrum of the fiducial model. Red curves show 21 cm power spectrum with DM particle annihilation through$ \chi\chi\rightarrow e^{+}e^{-} $ channel with$ m_{\chi} = 10 \; {\rm{GeV}} $ and$ \langle \sigma v \rangle = 10^{-26}\, {\rm{cm}}^{3}\,s^{-1} $ . Blue curves show 21 cm power spectrum with DM particle decay through$ \chi\rightarrow e^{+}e^{-} $ channel with$ m_{\chi} = 10 \; {\rm{GeV}} $ and$ \tau = 10^{27}\,{\rm{s}} $ . Green curves show 21 cm power spectrum with PBH Hawking radiation, with$ M_{{\rm{PBH}}} = 10^{16} \; {\rm{g}} $ and$ f_{{\rm{PBH}}} = 10^{-5} $ .We demonstrate how the 21 cm power spectrum responds to exotic energy injections and present the SKA's measurement errors on it, as shown in Fig. 2. The left panels display the redshift evolution of the 21 cm power spectrum at different scales, revealing peaks during cosmic dawn (

$ z \sim 10 - 15 $ ) and the epoch of reionization ($ z \sim 6 - 8 $ ). The peak during cosmic dawn is dominated by the heating and ionizing effects of the IGM, rendering the amplitude of this peak highly sensitive to energy injection processes such as DM particle annihilation, decay, and PBH Hawking radiation. During cosmic dawn, exotic heating increases the IGM kinetic temperature, thereby suppressing the 21 cm power spectrum amplitude. Subsequently, after heating saturation, rising ionization causes the cosmic dawn peak to diminish. Conversely, the peak during the epoch of reionization is governed by the ionizing effect of the IGM. According to Ref. [84], an increased ionization fraction amplifies the power spectrum during reionization. This opposing response stems from distinct physical mechanisms, ionization reduces neutral hydrogen density during cosmic dawn, but enhances fluctuations in the ionized bubble during reionization. The right panels show the scale dependence of the 21 cm power spectrum at fixed redshifts. Exotic energy injections enhance the amplitude of the power spectrum at$ z = 8.2 $ , but suppress it at$ z = 10.6 $ , consistent with Ref. [84]. Crucially, near the redshift of the cosmic dawn peak, both the amplitude of the 21 cm power spectrum and the corresponding signal-to-noise ratio increase significantly. Consequently, cosmic dawn emerges as the optimal observational window for the SKA to probe DM. -

To quantify the sensitivity of the SKA in probing DM particles and PBHs, we employ the Fisher information matrix. Assuming Gaussian posterior distributions for relevant parameters, the Fisher matrix for the 21 cm power spectrum is given by [75]

$ \begin{aligned}[b] F_{ij} =\;& \sum_{l}^{N_z}\sum_{m}^{N_k} \frac{1}{\sigma_{{\rm{tot}}}^2(z_{l},k_{m})}\frac{\partial [\overline{\delta T_{b}}^{2}(z_{l})\Delta_{21}^2(z_{l},k_{m} )]} {\partial \theta_i} \\&\times \frac{\partial [\overline{\delta T_{b}}^{2} (z_{l})\Delta_{21}^2(z_{l},k_{m} )]} {\partial \theta_j}\ . \end{aligned} $

(15) In this work, we discretize the 21 cm power spectrum into

$ N_k \times N_z $ independent bins, following Ref. [79].$ N_k $ and$ N_z $ represent the numbers of linearly discretized bins in k and z, respectively. The k range is from 0.2 to 0.9$ {{\rm{Mpc}}}^{-1} $ , and the z range is from 6 to 20.$ \sigma_{{\rm{tot}}}^2(z_{l},k_{m}) $ is the total noise for the 21 cm power spectrum in the redshift bin$ z_{l} $ and wavenumber bin$ k_{m} $ .$ \theta_{i} $ and$ \theta_{j} $ represent the i-th and j-th parameter in the parameter set.The total noise on the 21 cm power spectrum measurement results from three key sources [80]:

$ \sigma_{{\rm{tot}}}^2 \equiv \left[0.2 \overline{\delta T_{b}}^{2}\Delta_{21}^2\right]^2 + \sigma_{{\rm{poisson}}}^2 + \sigma_{{\rm{ins}}}^{2}\ , $

(16) where the first term represents a conservative 20% theoretical uncertainty in modeling the 21 cm signal [81], the second term quantifies the cosmic variance due to finite simulation volume, and the third term denotes instrumental noise dominated by the system temperature [80]. The instrumental noise is related to the square of system temperature, i.e.,

$ \sigma_{{\rm{ins}}} \propto T_{{\rm{sys}}}^{2} $ , whereas the system temperature can be estimated by [80]$ T_{{\rm{sys}}}(\nu) = 16.3 \times 10^6 \, {{\rm{K}}} \left(\frac{\nu}{2\, {{\rm{MHz}}}}\right)^{-2.53} \ . $

(17) In this work, we adopt this system temperature in the

$\mathrm{21cmSense}$ package [80] to estimate the instrumental noise of the SKA. We adopt stations in the central area of the SKA1-low (an array of 295 stations, where the diameter of each station is 35 m, distributed across a circular area with a diameter of$ 1.7 $ km), observing with a total bandwidth of$ 8\,{{\rm{MHz}}} $ , spectral resolution of$ 100\,{{\rm{kHz}}} $ , and total integration time of 10,000 h [82]. The marginalized uncertainty for a specific parameter$ \theta_{i} $ satisfies$ \sigma_{\theta_{i}} \geq \sqrt{(F^{-1})_{ii}} $ [83]. This suggests that the Fisher matrix provides conservative lower bounds on parameter constraints. The$ 1\sigma $ uncertainty of parameter$ \theta_{i} $ is its standard deviation. Furthermore, the correlation between parameters$ \theta_{i} $ and$ \theta_{j} $ is quantified by dimensionless correlation coefficient$ R_{ij} = C_{ij}/\sqrt{ C_{ii} C_{jj} } $ , where covariance matrix$ C_{ij} $ is the inverse of Fisher matrix$ F_{ij} $ .Our model incorporates two categories of independent parameters, which are astrophysical parameters and parameters for DM particles and PBHs. Astrophysical parameters follow the conventions of

$\mathrm{21cmFAST}$ , including$ t_{\star} $ ,$ a_{\star} $ ,$ a_{{\rm{esc}}} $ ,$ {{\rm{log}}}_{10}f_{\star} $ ,$ {{\rm{log}}}_{10}f_{{\rm{esc}}} $ , and$ {{\rm{log}}}_{10}L_{{\rm{X}}} $ , where$ t_{\star} $ is the dimensionless star formation timescale,$ a_{\star} $ represents the power-law index of stellar-to-halo mass ratio,$ a_{{\rm{esc}}} $ represents the power-law index of UV photon escape fraction,$ {{\rm{log}}}_{10}f_{\star} $ represents the stellar-to-halo mass ratio,$ {{\rm{log}}}_{10}f_{{\rm{esc}}} $ represents the UV escape fraction, and$ {{\rm{log}}}_{10}L_{{\rm{X}}} $ represents X-ray luminosity per star formation rate in unit of$ {{\rm{erg}}} {\rm \cdot yr \cdot sec^{-1}} M^{-1}_{\odot} $ , where$ M_{\odot} $ is the solar mass. The remaining parameters correspond to DM physics.$ \langle \sigma v \rangle $ characterizes the annihilation cross section of DM particles, in units of$ {{\rm{cm}}}^{3}\; s^{-1} $ .$ \Gamma = \tau^{-1} $ represents the decay rate of DM particles, in units of$ {{\rm{s}}}^{-1} $ .$ f_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ signifies the abundance of PBHs. For the fiducial model in Fig. 2, the astrophysical parameters are set to$ t_{\star} = 0.5 $ ,$ a_{\star} = 0.5 $ ,$ a_{{\rm{esc}}} = -0.5 $ ,$ {{\rm{log}}}_{10}f_{\star} = -1.3 $ ,$ {{\rm{log}}}_{10}f_{{\rm{esc}}} = -1.0 $ , and$ {{\rm{log}}}_{10}L_{{\rm{X}}} = $ 40.0, whereas the DM and PBH parameters,$ \langle \sigma v \rangle $ , Γ, and$ f_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ are set to zero.

Figure 2. (color online) 21 cm power spectrum under different energy injection scenarios. Left-hand panels: 21 cm power spectrum as a function of redshift z at fixed scales

$ k = 0.2 \,{{\rm{Mpc}}}^{-1} $ and$ k = 0.73\,{{\rm{Mpc}}}^{-1} $ . Right-hand panels: 21 cm power spectrum as a function of the scale at redshift$ z = 8.2 $ and$ z = 10.6 $ . In each panel, the instrumental noise is shown by the shaded region. Black curves show the 21 cm power spectrum of the fiducial model. Red curves show 21 cm power spectrum with DM particle annihilation through$ \chi\chi\rightarrow e^{+}e^{-} $ channel with$ m_{\chi} = 10 \; {\rm{GeV}} $ and$ \langle \sigma v \rangle = 10^{-26}\, {\rm{cm}}^{3}\,s^{-1} $ . Blue curves show 21 cm power spectrum with DM particle decay through$ \chi\rightarrow e^{+}e^{-} $ channel with$ m_{\chi} = 10 \; {\rm{GeV}} $ and$ \tau = 10^{27}\,{\rm{s}} $ . Green curves show 21 cm power spectrum with PBH Hawking radiation, with$ M_{{\rm{PBH}}} = 10^{16} \; {\rm{g}} $ and$ f_{{\rm{PBH}}} = 10^{-5} $ .We demonstrate the response of the 21 cm power spectrum to exotic energy injections and present the SKA's measurement errors on it, as shown in Fig. 2. The left-hand panels display the redshift evolution of the 21 cm power spectrum at different scales, revealing peaks during cosmic dawn (

$ z \sim 10 - 15 $ ) and the epoch of reionization ($ z \sim 6 - 8 $ ). The peak during cosmic dawn is dominated by the heating and ionizing effects of the IGM, rendering the amplitude of this peak highly sensitive to energy injection processes such as DM particle annihilation, decay, and PBH Hawking radiation. During cosmic dawn, exotic heating increases the IGM kinetic temperature, thereby suppressing the 21 cm power spectrum amplitude. Subsequently, after heating saturation, rising ionization causes the cosmic dawn peak to diminish. Conversely, the peak during the epoch of reionization is governed by the ionizing effect of the IGM. According to Ref. [84], an increased ionization fraction amplifies the power spectrum during reionization. This opposing response results from distinct physical mechanisms; ionization reduces neutral hydrogen density during cosmic dawn but enhances fluctuations in the ionized bubble during reionization. The right-hand panels show the scale dependence of the 21 cm power spectrum at fixed redshifts. Exotic energy injections enhance the amplitude of the power spectrum at$ z = 8.2 $ but suppress it at$ z = 10.6 $ , consistent with Ref. [84]. Crucially, near the redshift of the cosmic dawn peak, both the amplitude of the 21 cm power spectrum and corresponding signal-to-noise ratio increase significantly. Consequently, the cosmic dawn emerges as the optimal observational window for the SKA to probe DM. -

In this section, we present the projected sensitivity of the SKA for probing DM particles and PBHs. We further compare this sensitivity with existing constraints from astrophysical probes.

-

In this section, we present the projected sensitivity of the SKA for probing DM particles and PBHs. We further compare this sensitivity with existing constraints from astrophysical probes.

-

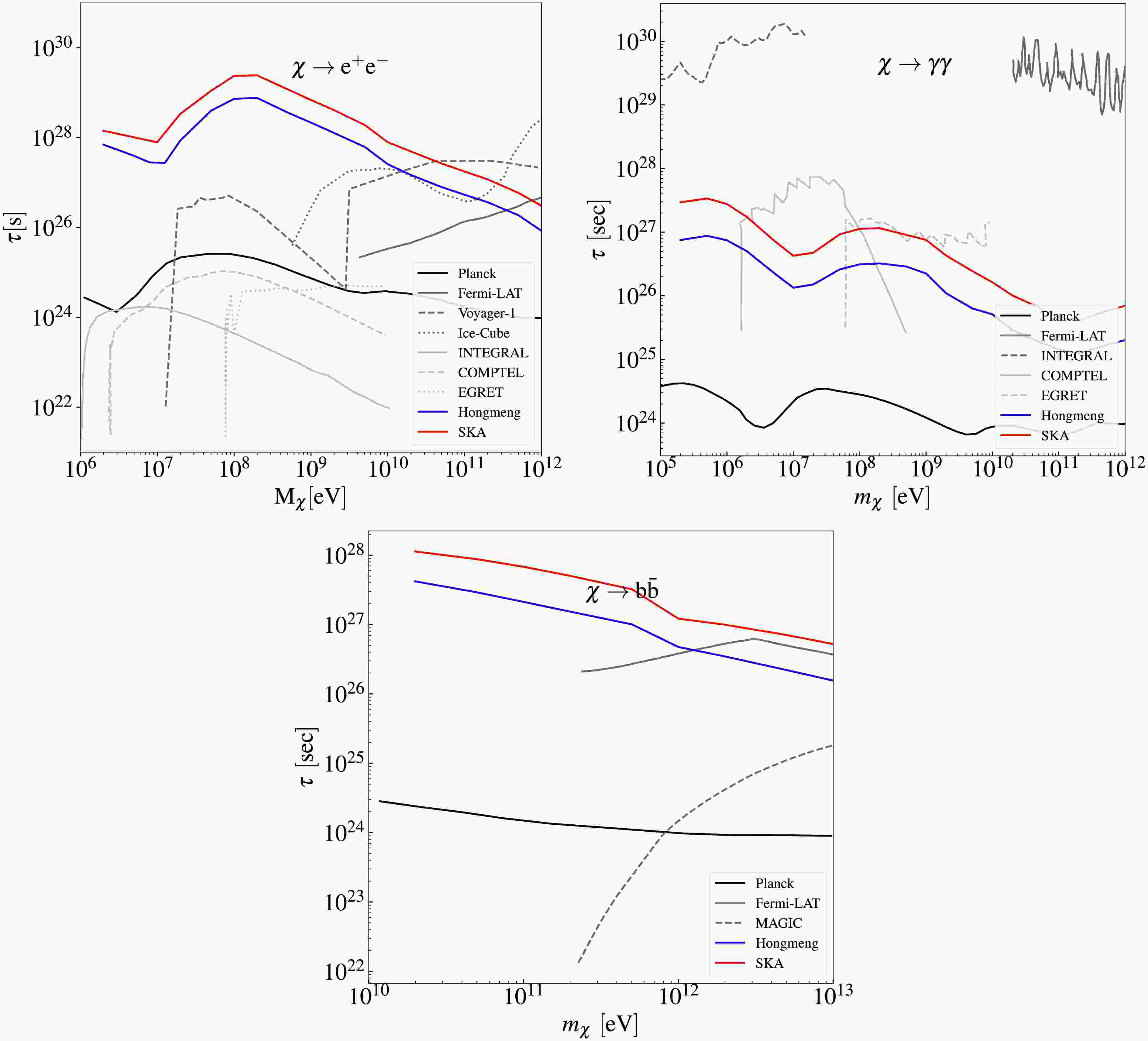

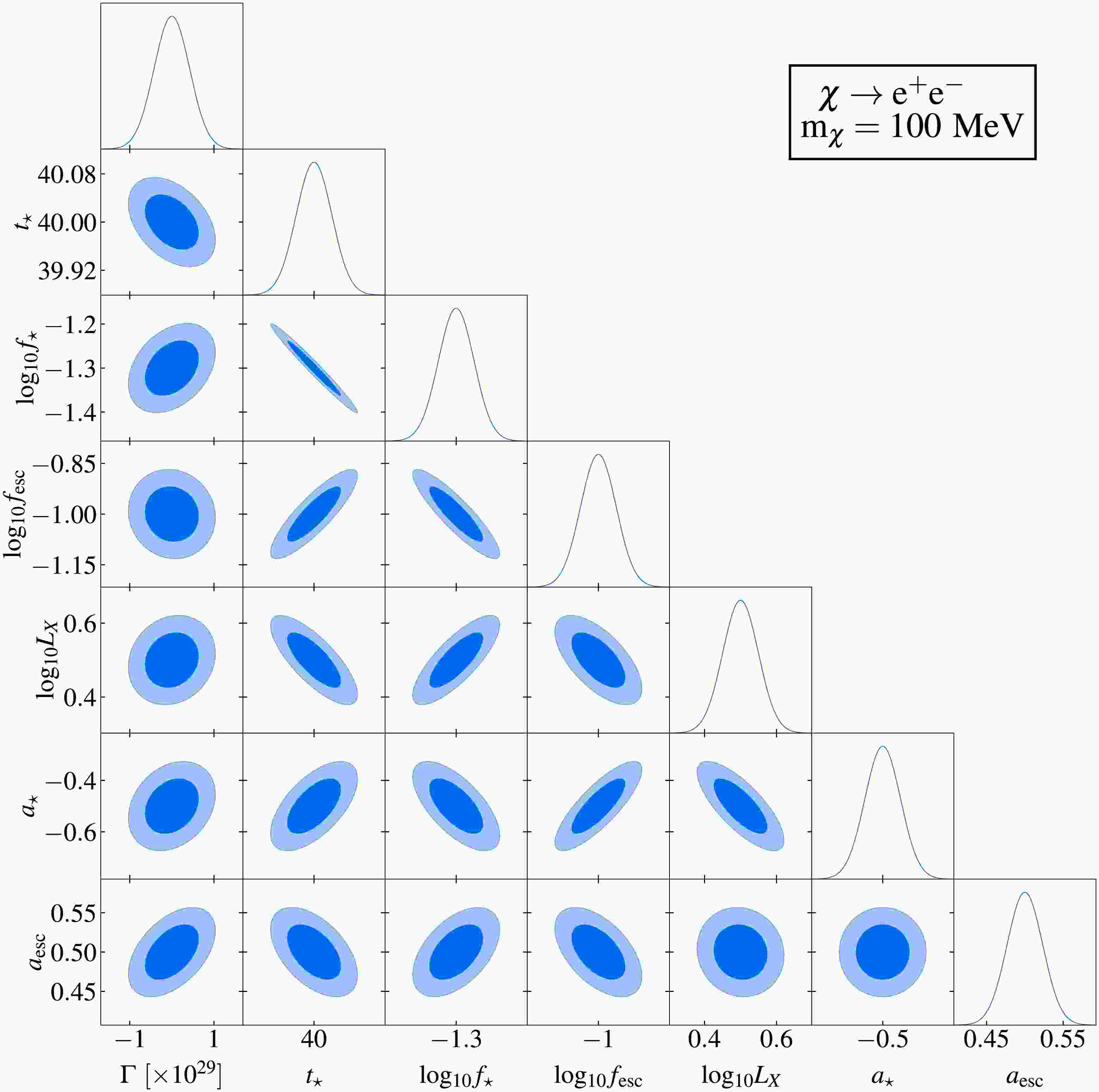

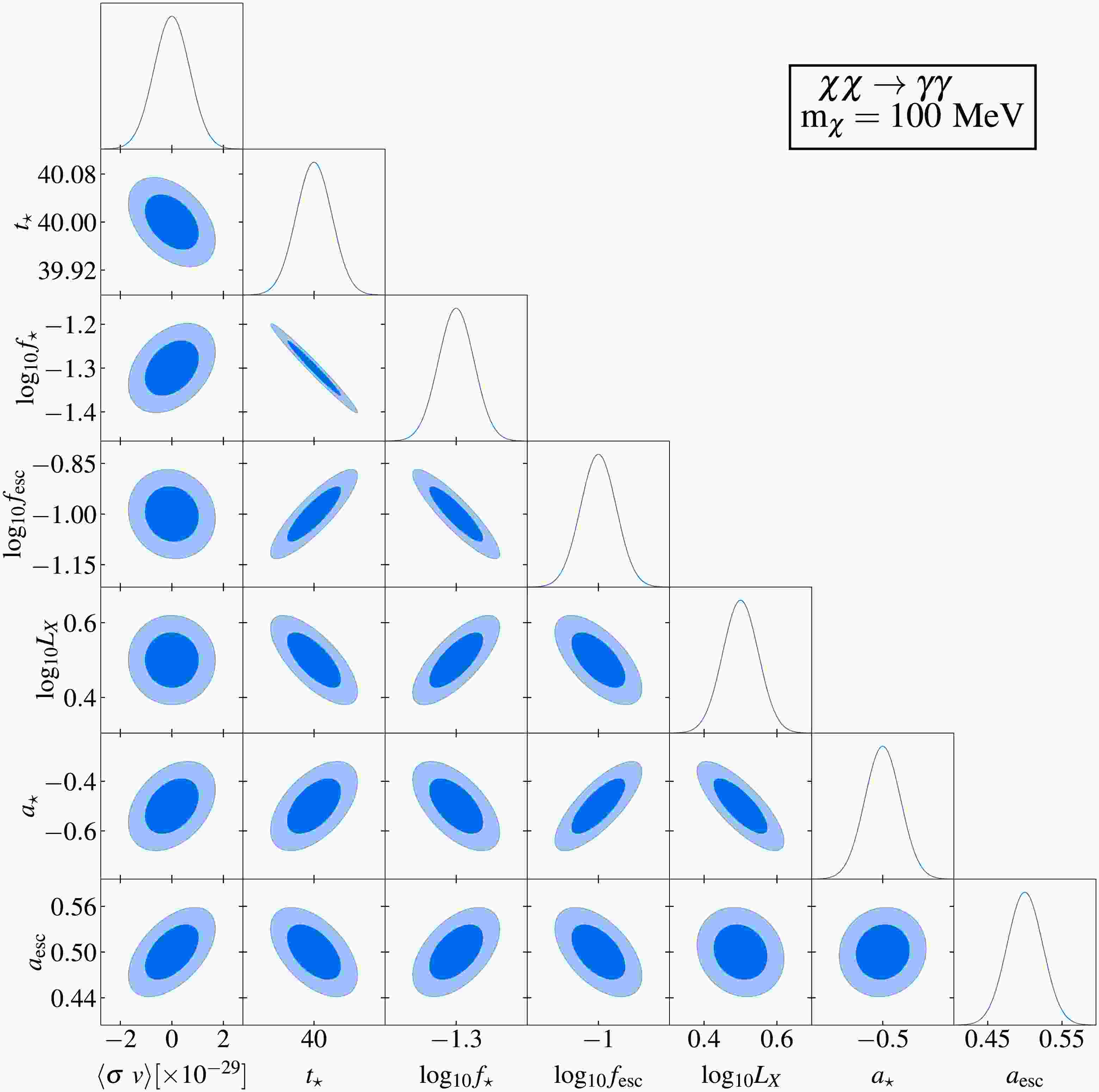

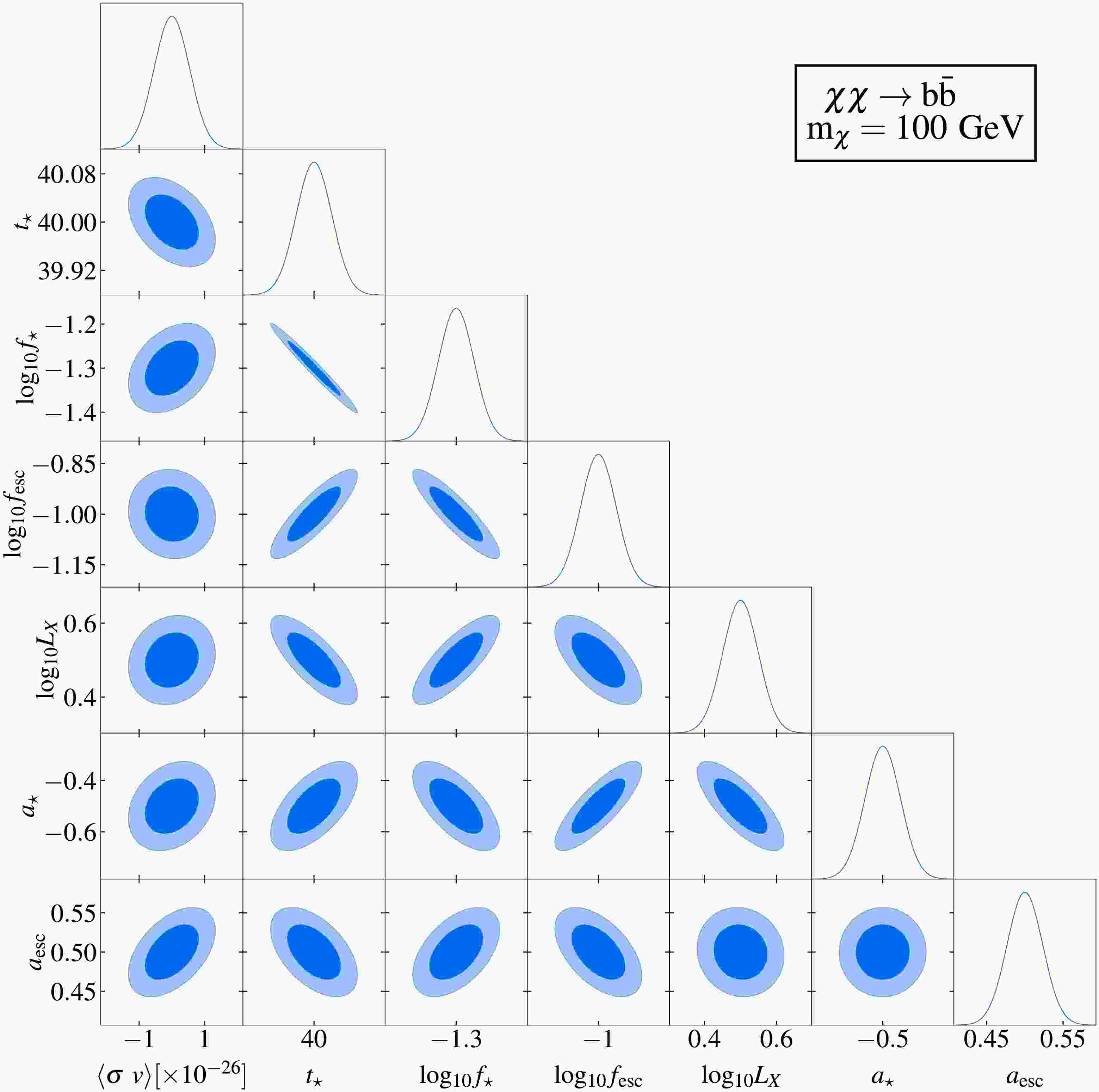

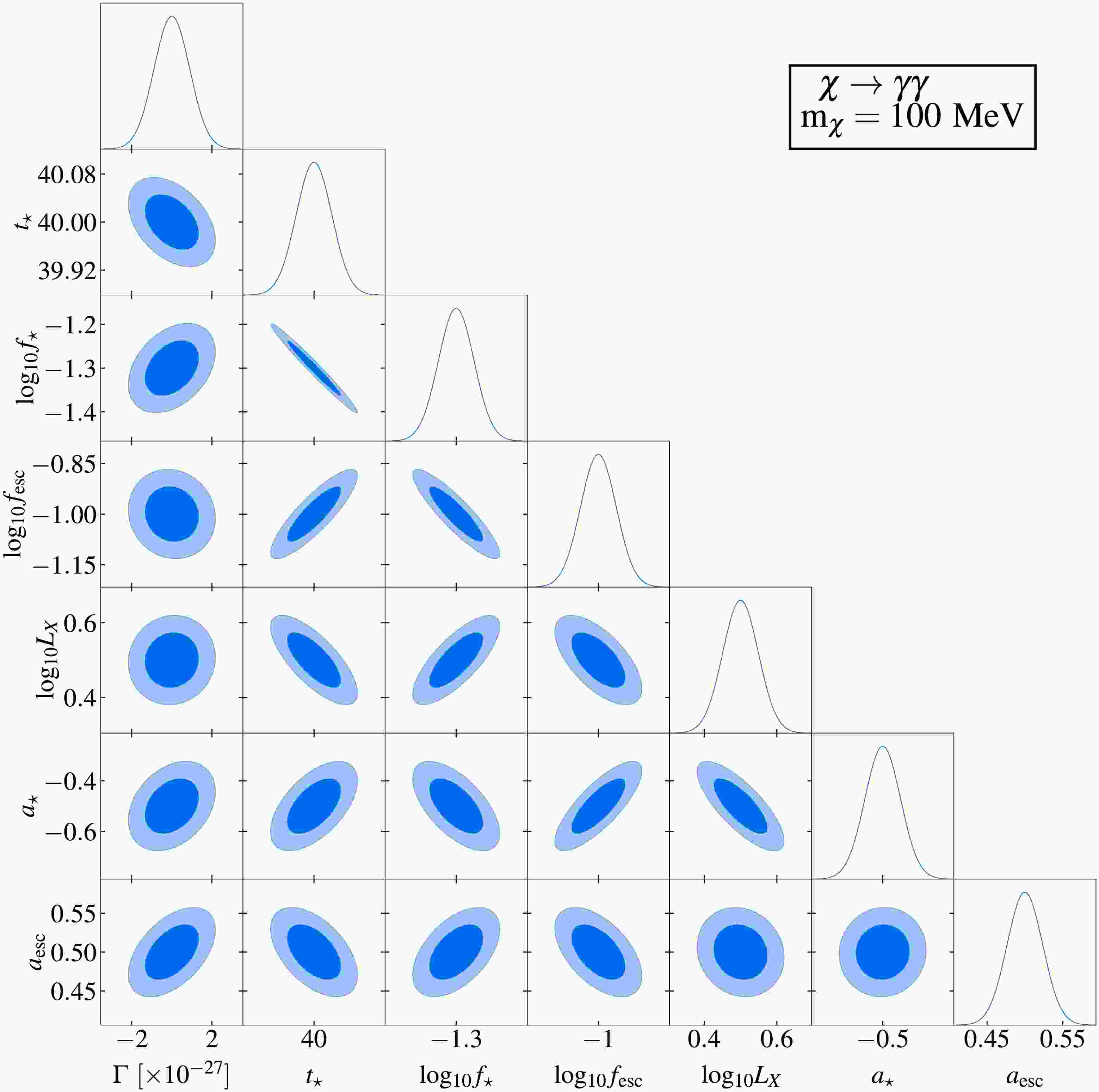

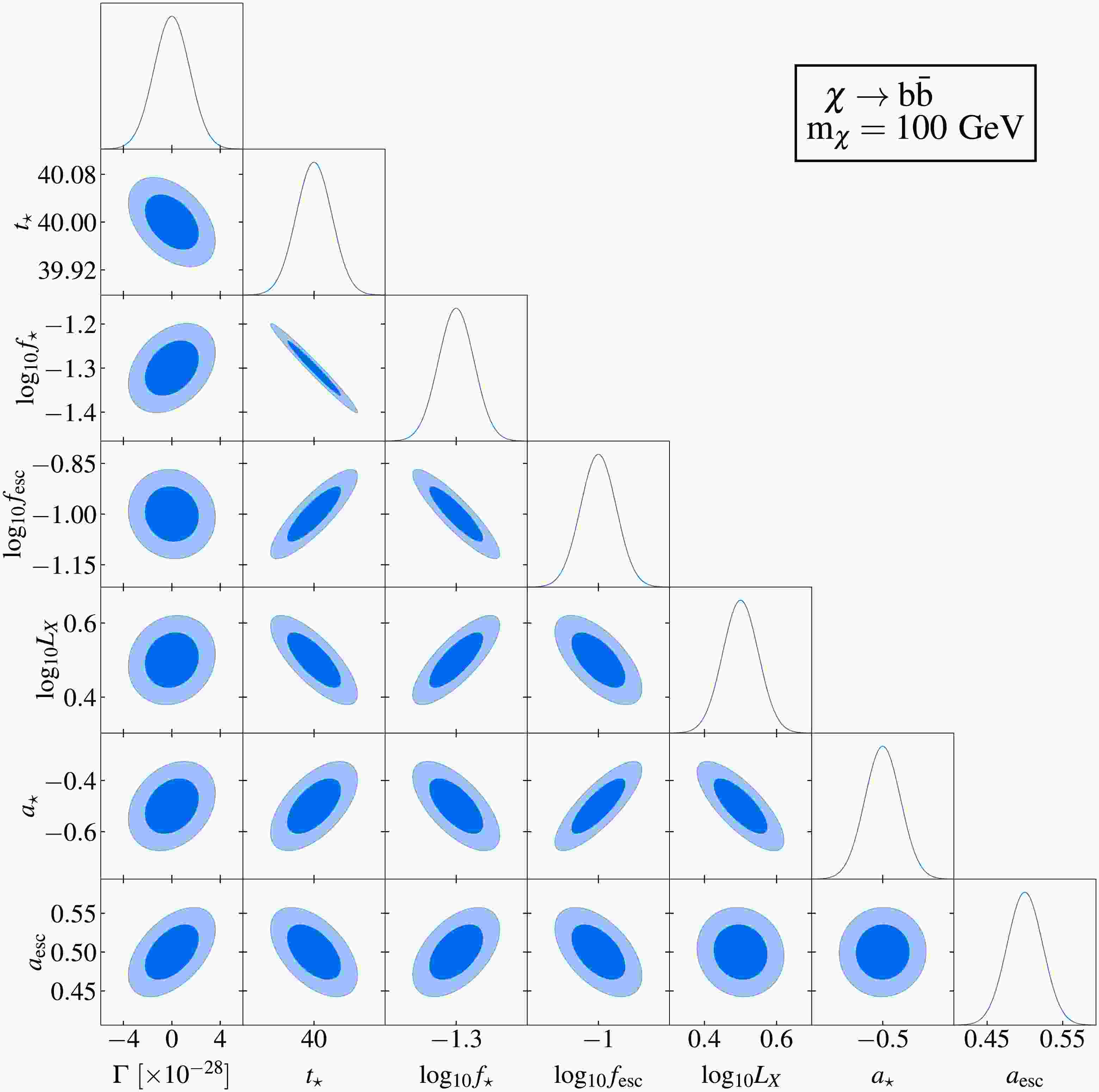

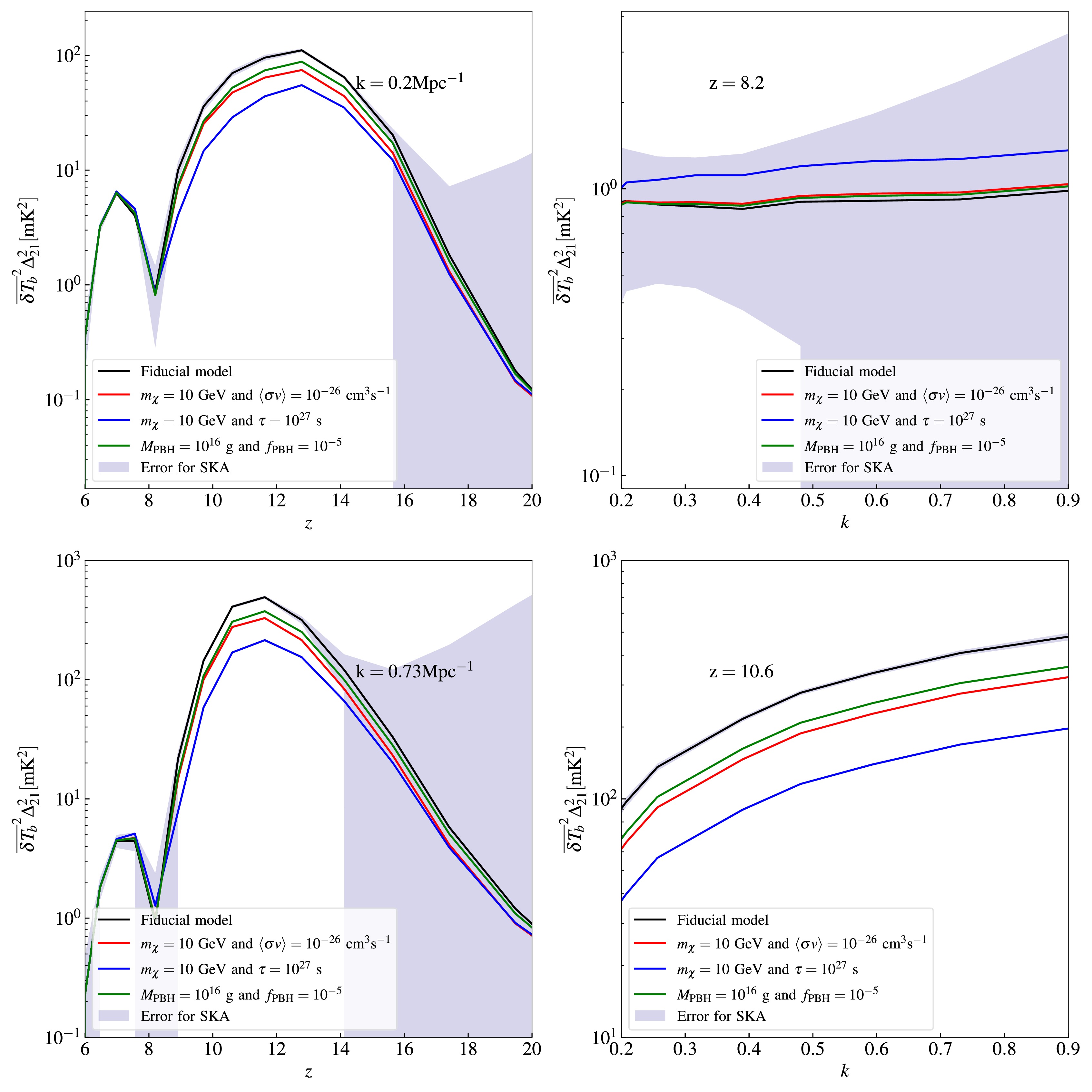

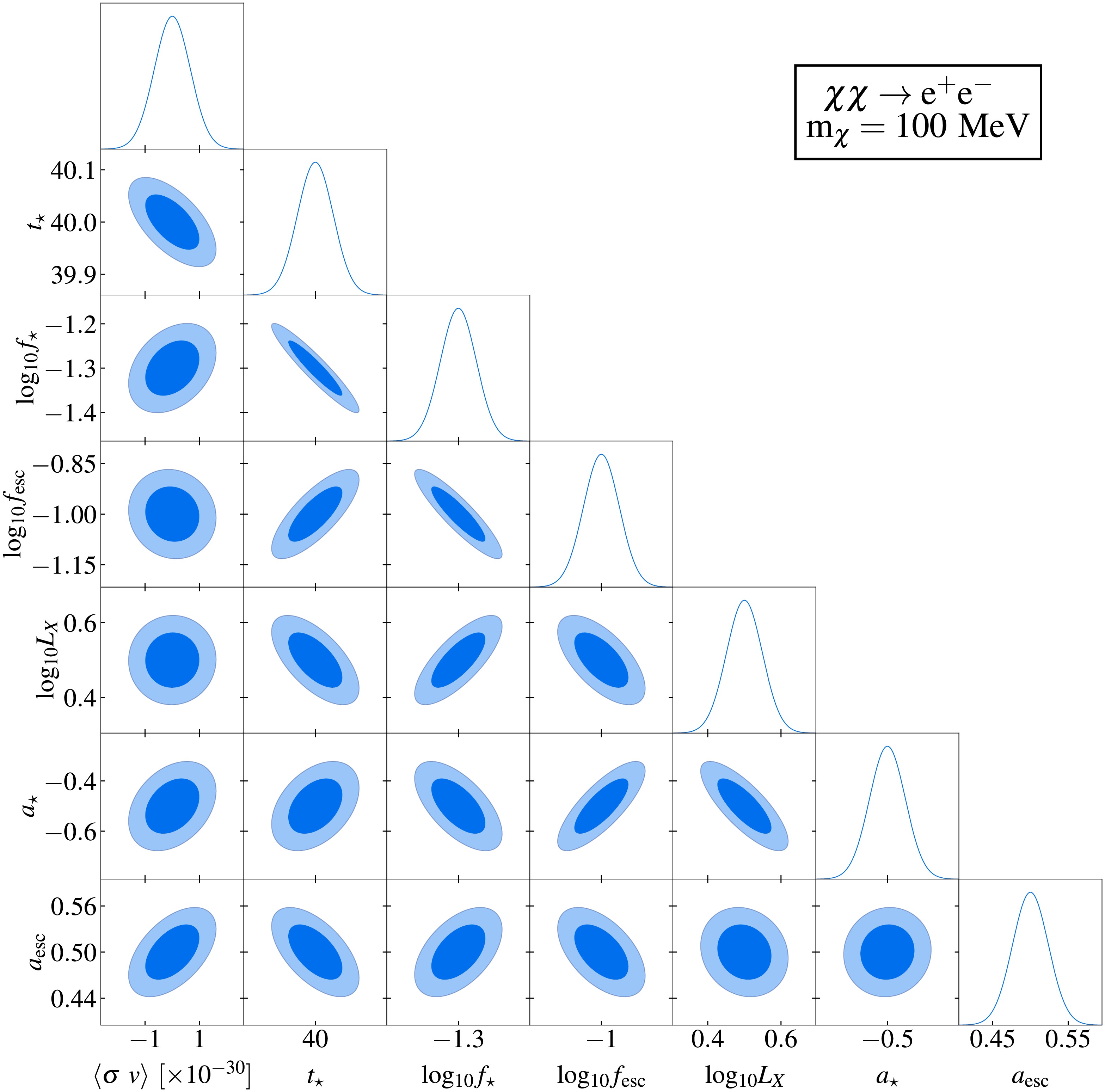

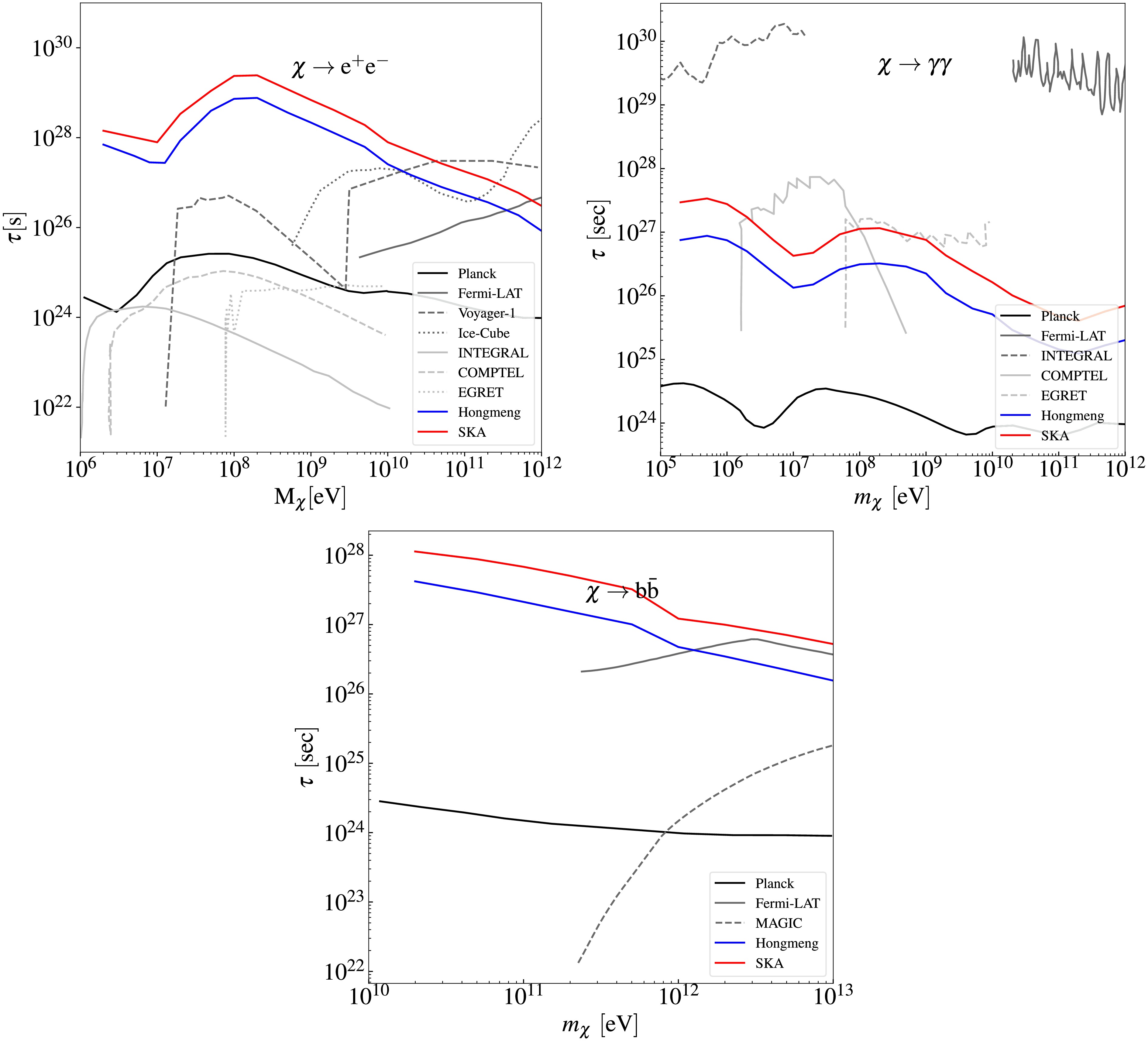

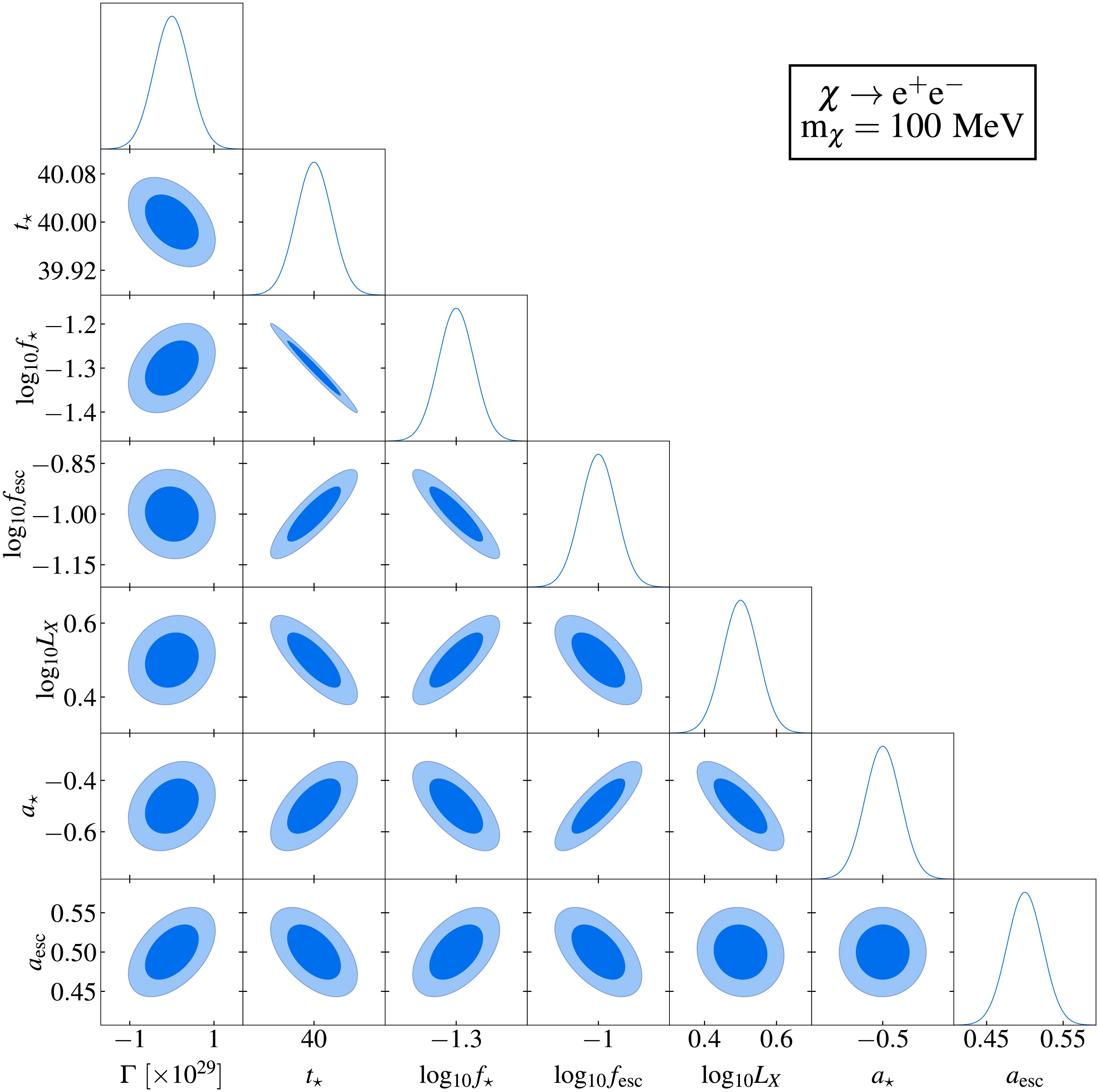

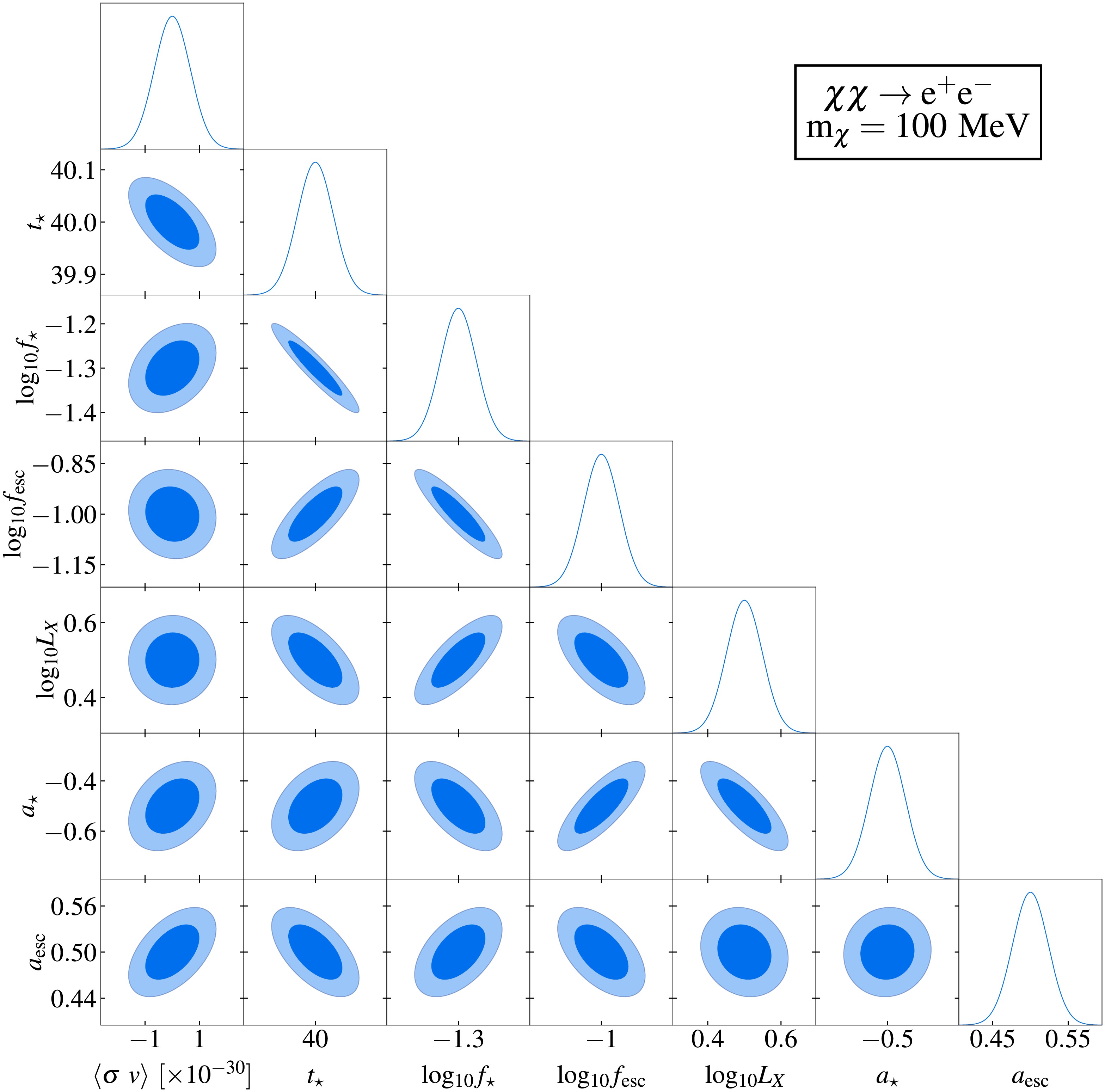

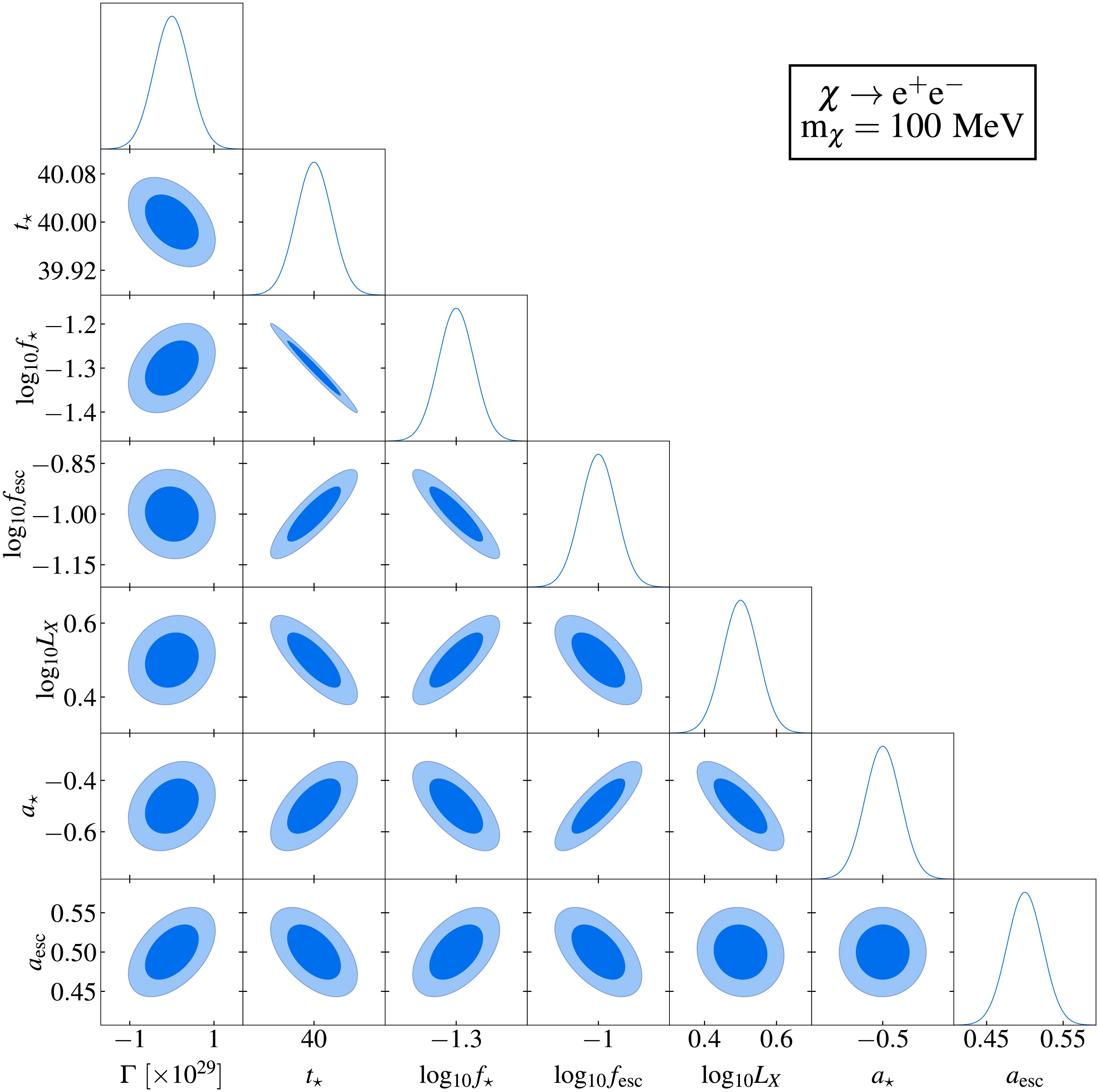

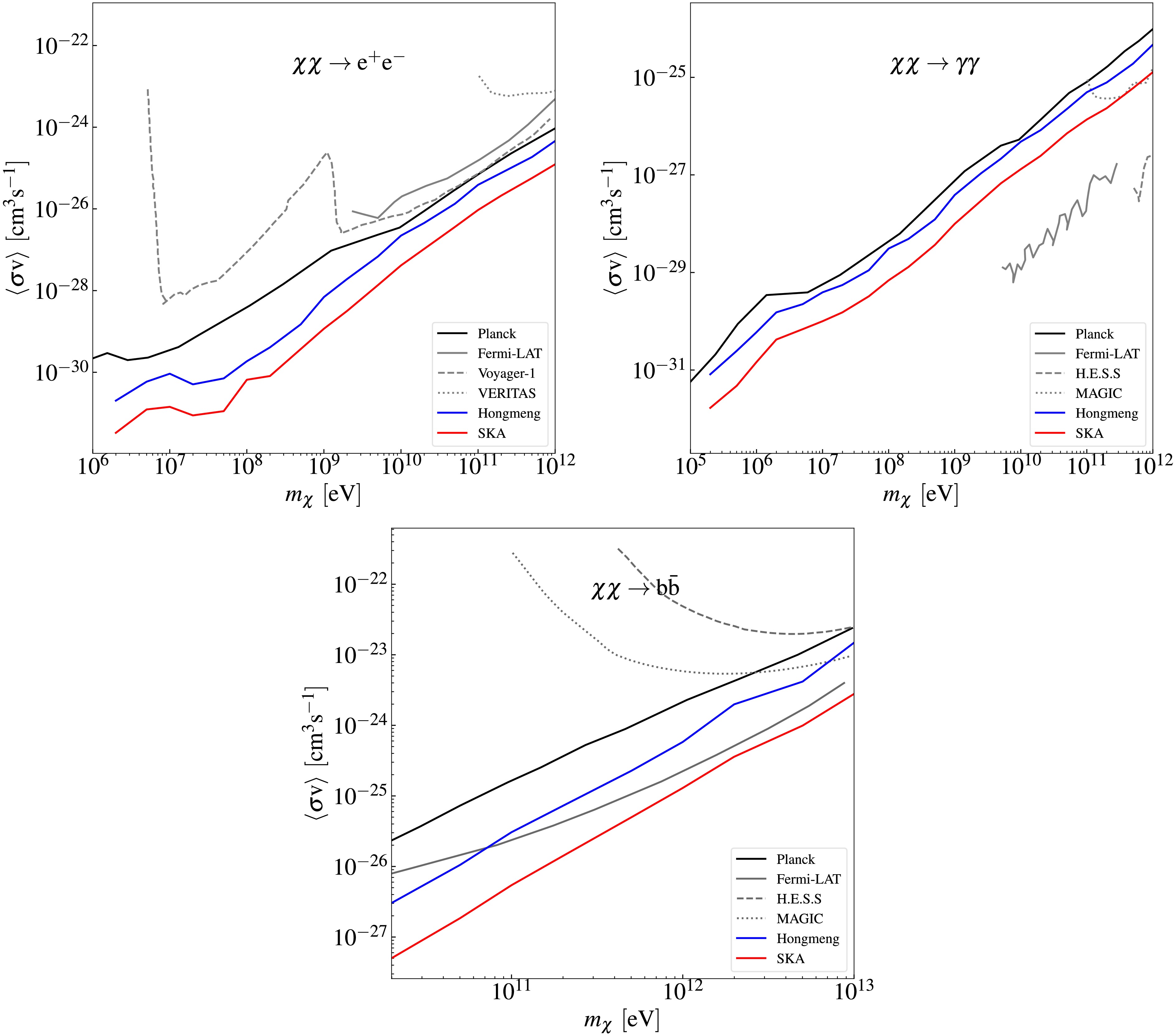

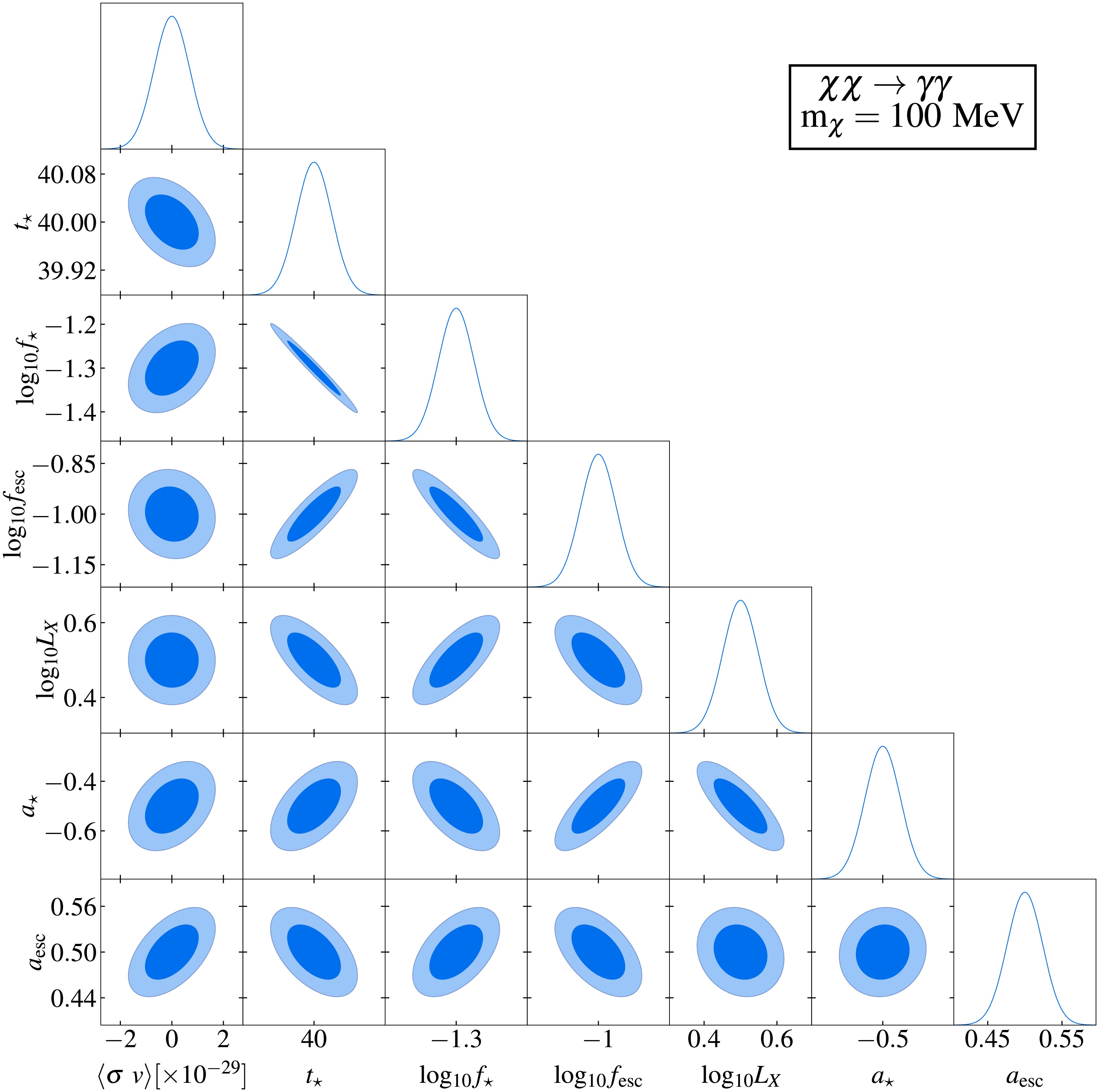

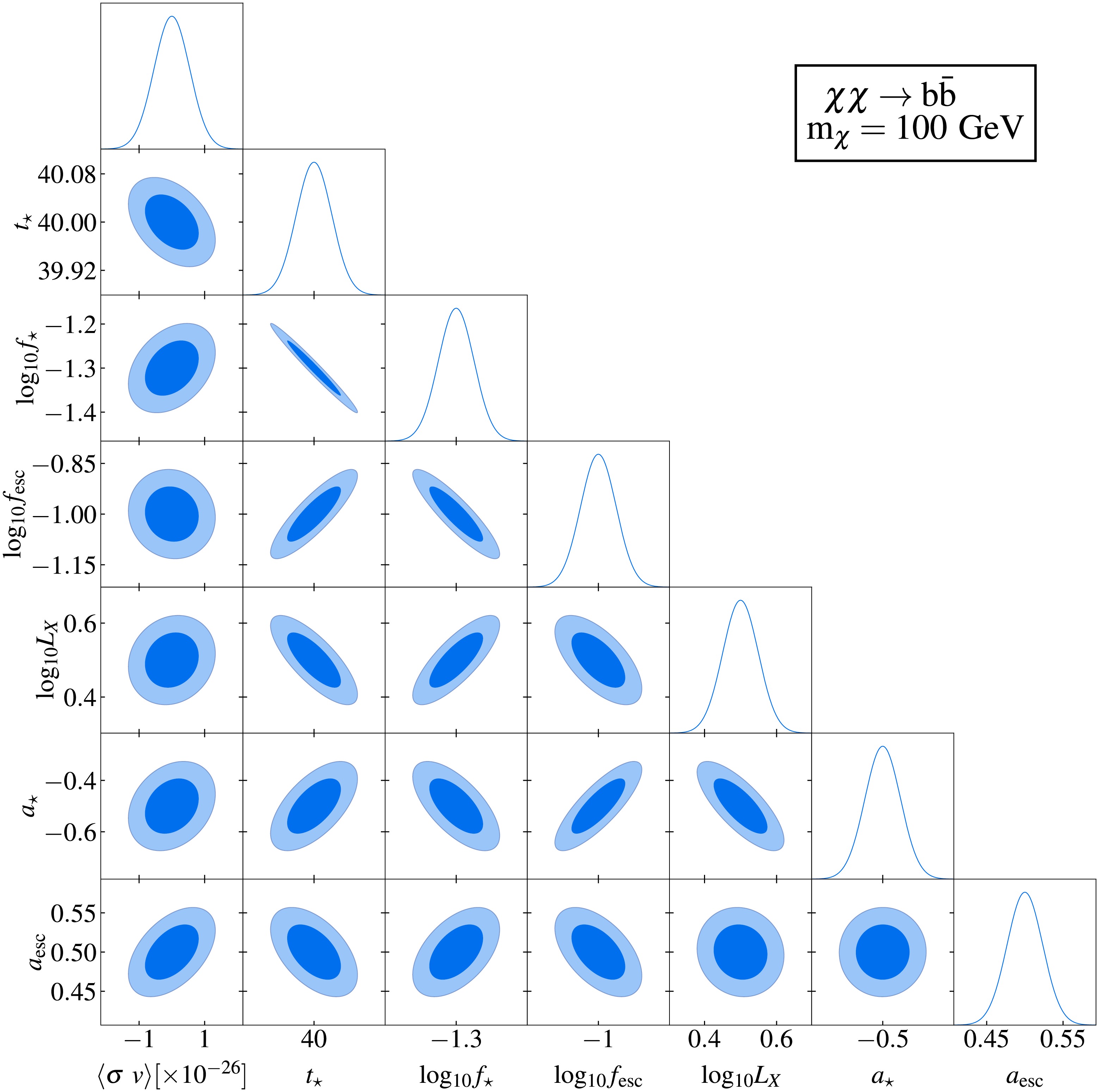

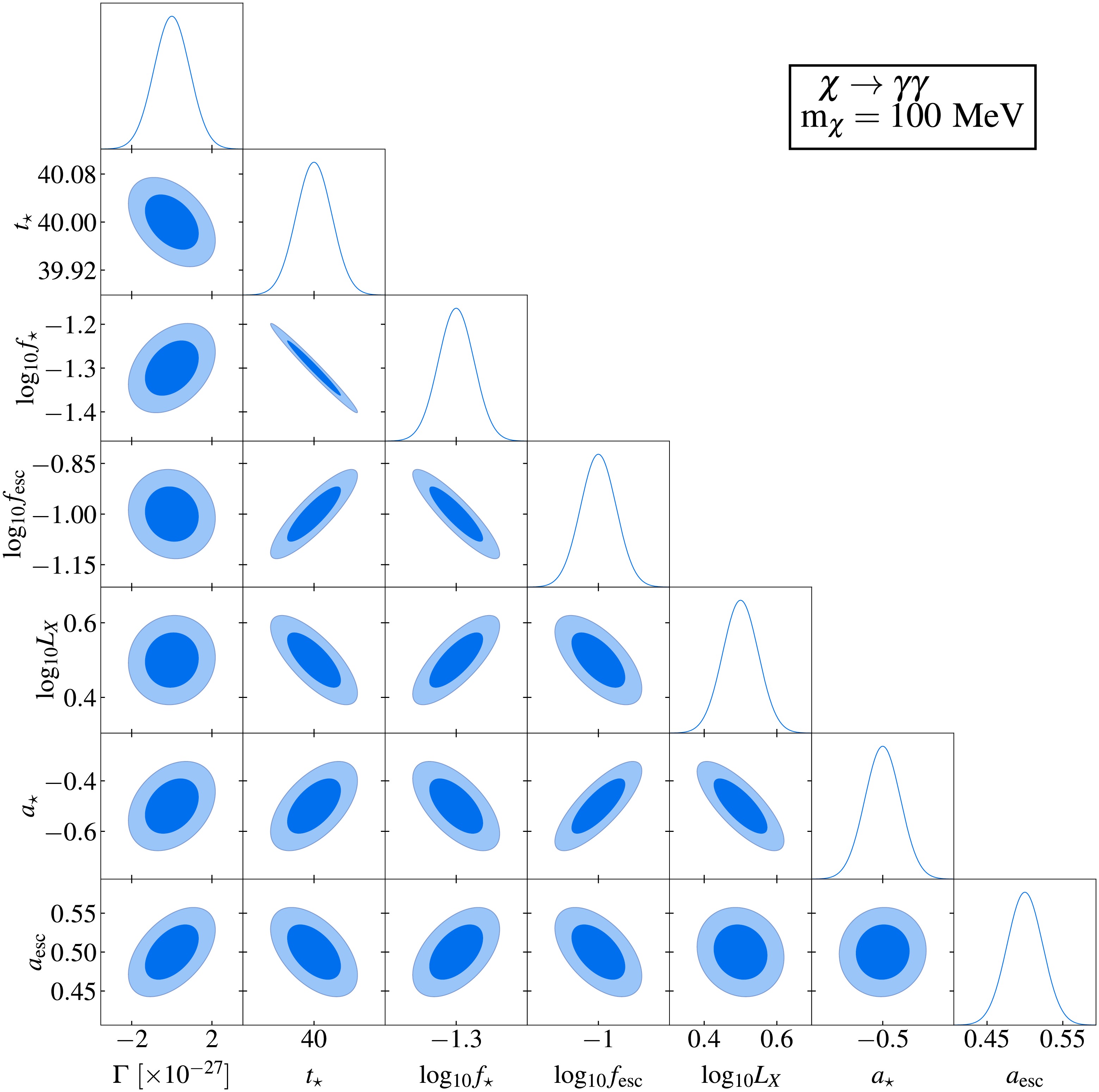

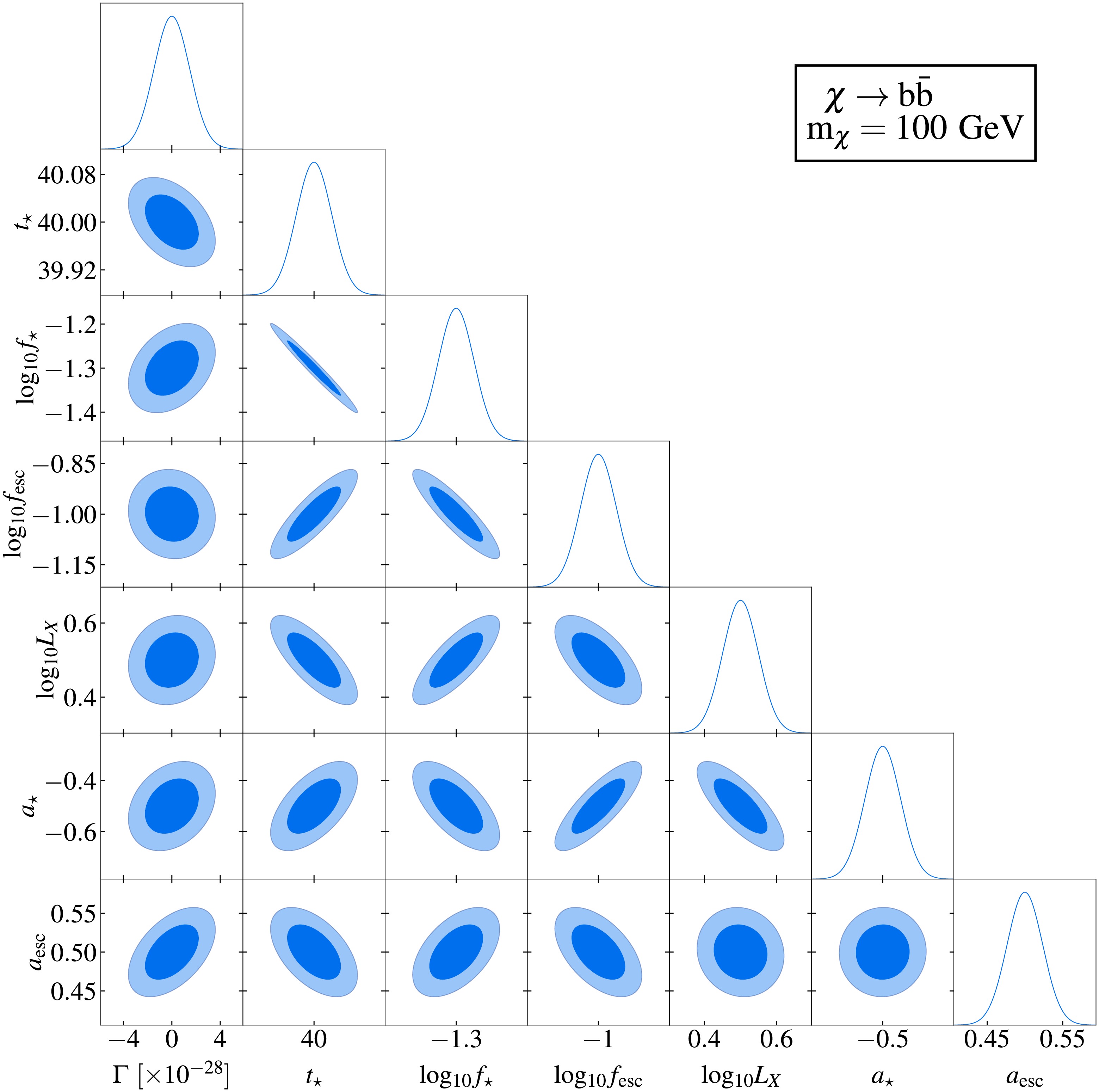

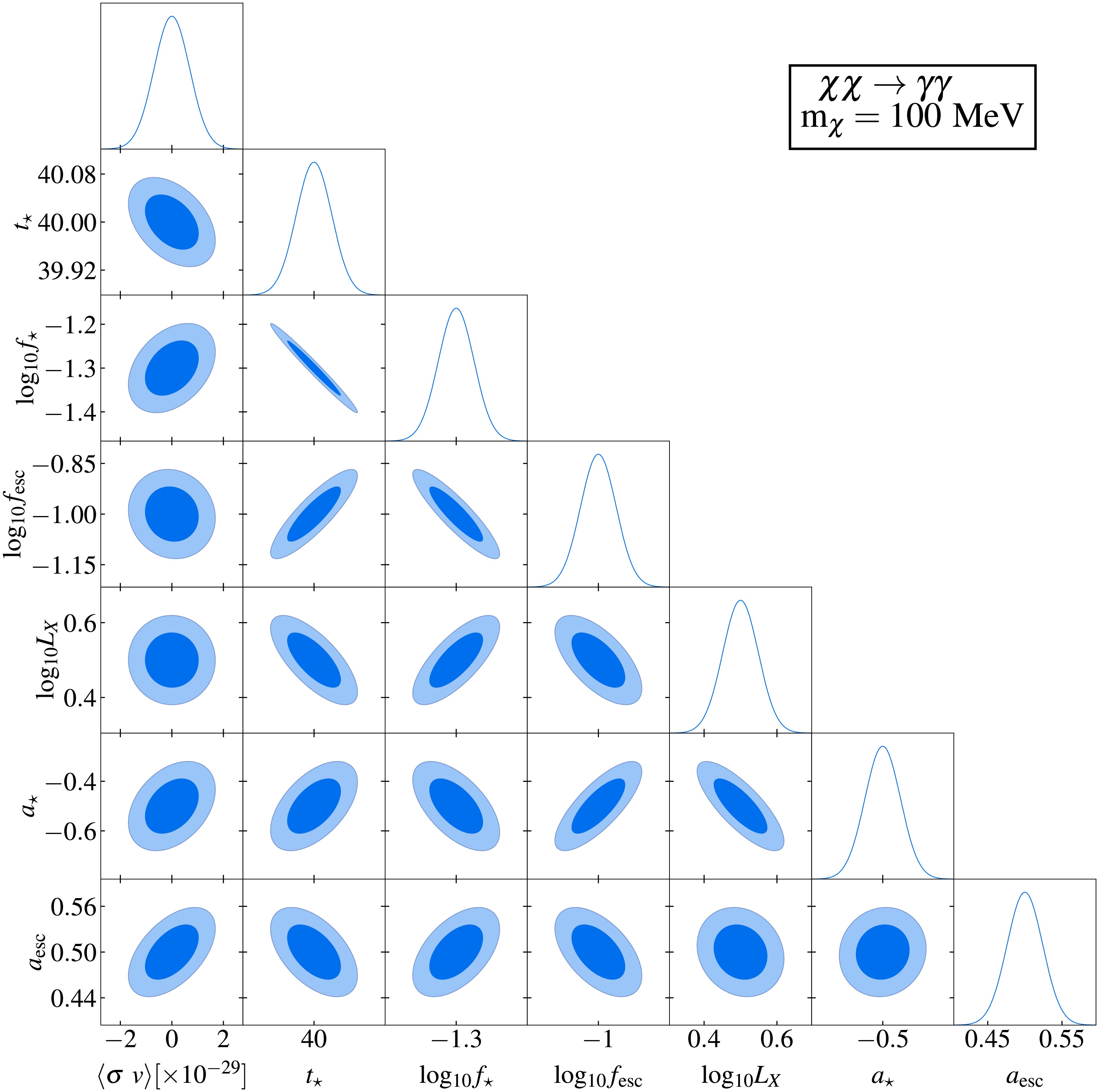

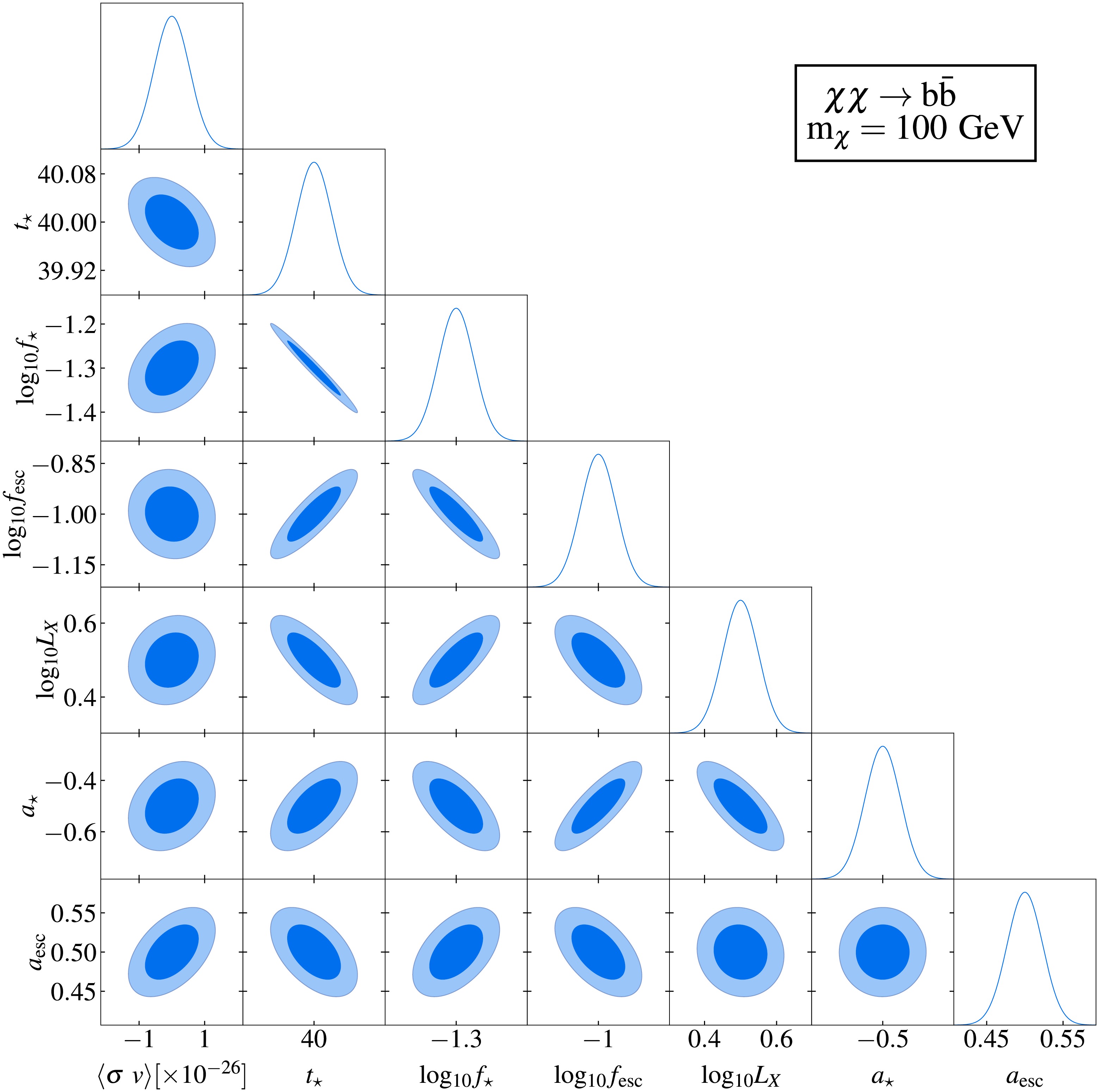

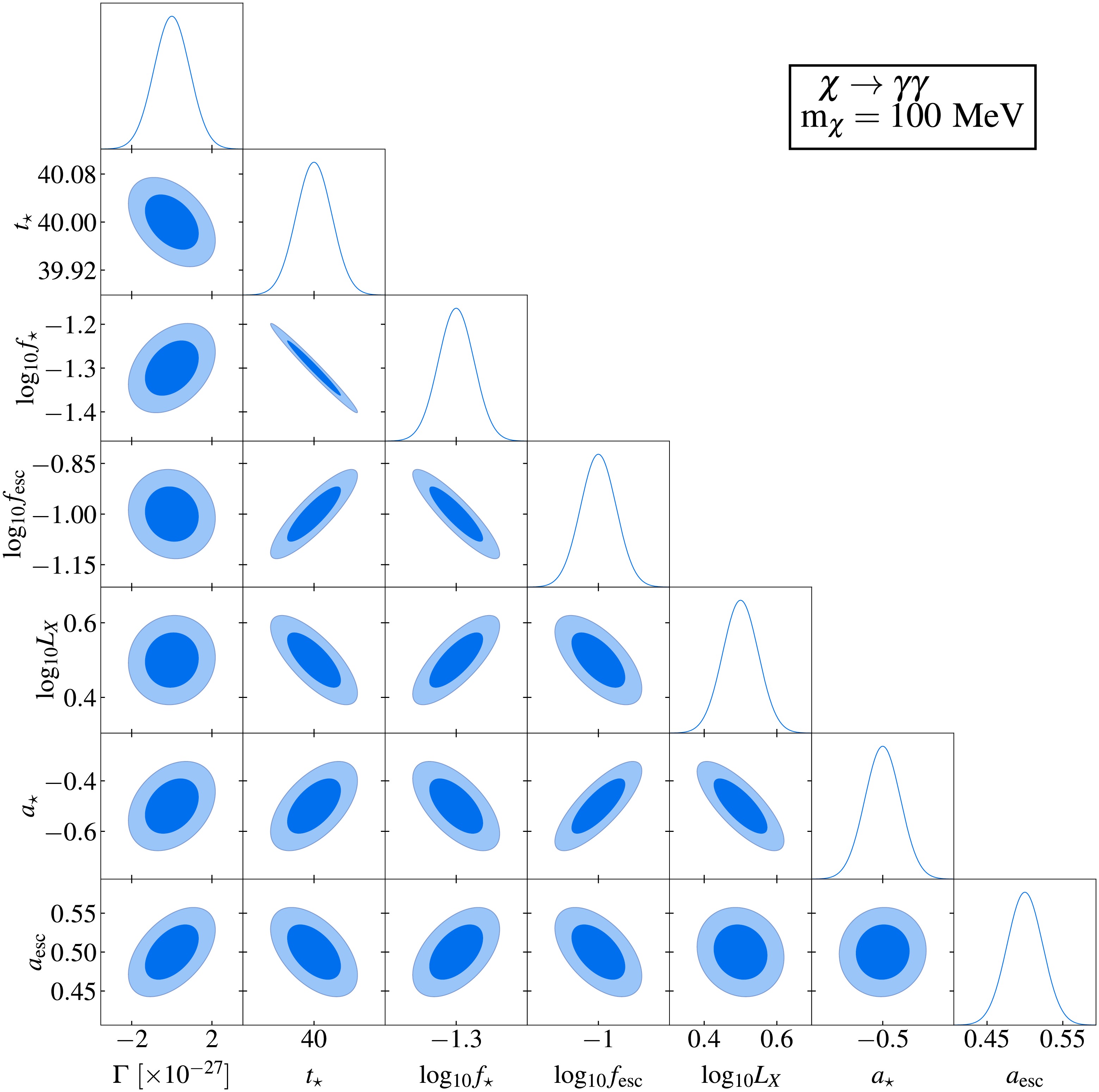

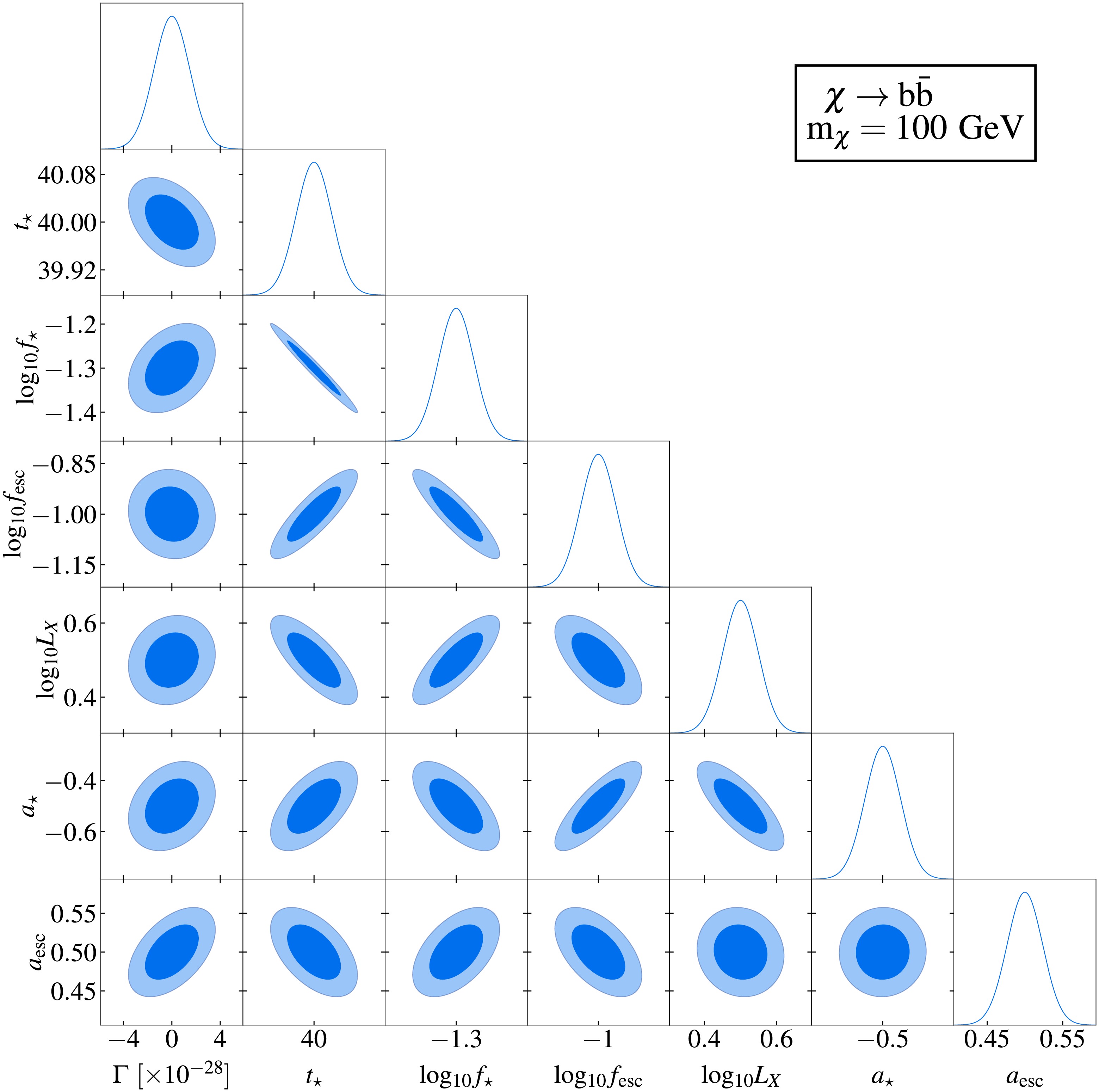

The results of the Fisher information matrix analysis are summarized in Figs. 3–6. Figs. 3 and 5 display two representative corner plots that characterize parameter correlations and constraints, assuming a fixed DM particle mass of 100 MeV and an integration time of 10,000 hours. The

$ 1\sigma $ and$ 2\sigma $ confidence intervals are represented by the dark and light shaded areas, respectively, while the solid curves depict the marginalized posterior distributions. Fiducial model parameters in these figures are consistent with those in Fig. 2. Complete corner plots are provided in Appendix A. Figs. 4 and 6 quantify the projected sensitivity at$ 1\sigma $ confidence level for SKA's capability to probe DM and compare these results with existing constraints at$ 2\sigma $ confidence level from CMB observations [30], gamma ray measurements [45, 49−51, 55, 57, 58], electron-positron pair observations [48, 52, 53], and 21 cm global spectrum measurements [21].

Figure 3. (color online) Fisher forecast for probing DM annihilation through the

$ \chi \chi \rightarrow e^{+} e^{-} $ channel using the 21 cm power spectrum by the SKA.$ 1\sigma $ and$ 2\sigma $ confidence intervals are represented by dark and light shaded areas, respectively, with solid curves indicating the marginalized posteriors. Fiducial model used is consistent with that shown in Fig. 2. The assumed DM particle mass is$ m_{\chi} = 100 $ MeV, integrated over 10,000 hours.

Figure 6. (color online) Prospective sensitivity of the SKA for probing the decay of DM particles through three channels. The

$ 1\sigma $ confidence-level sensitivity of the SKA project to the decay lifetime of DM particles (mass range$ 10^{6} $ -$ 10^{12}\,\text{eV} $ ) are shown by the red curves. Existing$ 2\sigma $ upper limits from observations of CMB distortion (black curve) [29, 33], extragalactic photons (gray curves) [41−43, 45, 53, 56, 60], and electron-positron pairs (gray dashed curve) [48, 53] are included for comparison. Prospective sensitivity of the 21 cm global spectrum (blue curve) is also taken into consideration [21].

Figure 5. (color online) Fisher forecast for probing DM decay through the

$ \chi \rightarrow e^{+} e^{-} $ channel using the 21 cm power spectrum by the SKA.$ 1\sigma $ and$ 2\sigma $ confidence intervals are represented by dark and light shaded areas, respectively, with solid curves indicating the marginalized posteriors. Fiducial model used is consistent with that shown in Fig. 2. The assumed DM particle mass is$ m_{\chi} = 100 $ MeV, integrated over 10,000 hours.

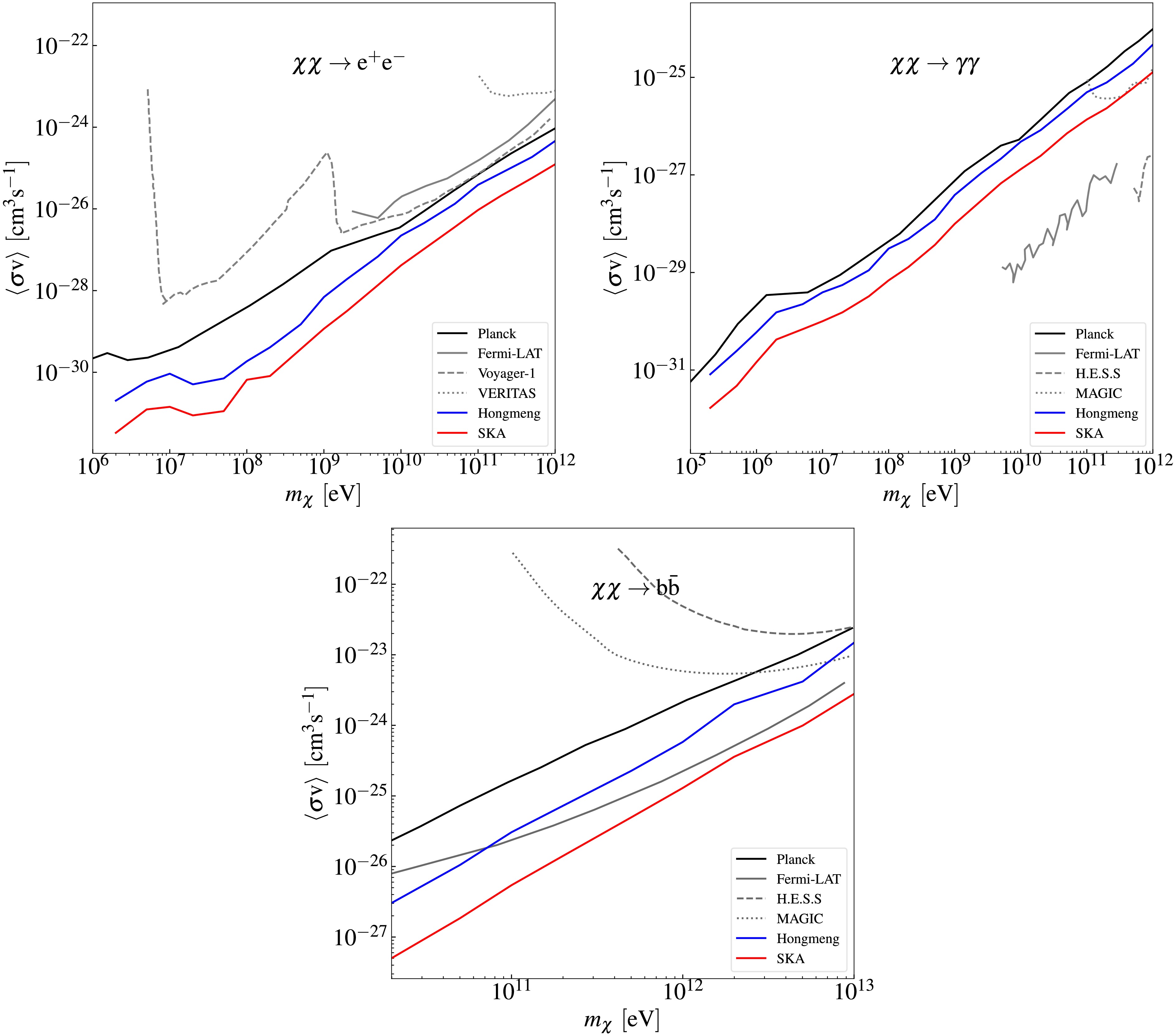

Figure 4. (color online) Prospective sensitivity of the SKA for probing the annihilation of DM particles through three channels. The

$ 1\sigma $ confidence-level sensitivity of the SKA to the thermally averaged annihilation cross section of DM particles (mass range$ 10^{6} $ -$ 10^{12}\,\text{eV} $ ) are shown by the red curves. Existing$ 2\sigma $ upper limits from observations of CMB distortion (black curve) [30], gamma-ray observations (gray curves) [45, 49−51, 55, 57, 58], and electron-positron pairs (gray dashed curve) [48, 53] are included for comparison. Prospective sensitivity of the 21 cm global spectrum (blue curve) [21] is also included for comparison.Figs. 3 and 5 reveal mild correlations between the annihilation and decay parameters of DM particles and the astrophysical parameters. This result indicates a limited degeneracy between the DM-induced exotic energy injection and astrophysical effects on the 21 cm power spectrum. Specifically,

$ \langle \sigma v \rangle $ and τ show weak positive correlations with$ a_{{\rm{esc}}} $ ,$ a_{\star} $ and$ \log_{10} f_{\star} $ , mild negative correlations with$ t_\star $ , and negligible correlations with$ L_{{\rm{X}}} $ and$ f_{{\rm{esc}}} $ . These results demonstrate the feasibility of constraining DM parameters and extracting key properties, particularly the thermally-averaged annihilation cross section$ \langle \sigma v \rangle $ and decay lifetime τ, using the 21 cm power spectrum. The weak degeneracies demonstrate that the 21 cm power spectrum can effectively constrain DM parameters independently of astrophysical uncertainties. This allows probing of fundamental DM properties, particularly$ \langle \sigma v \rangle $ and τ, with minimized contamination from astrophysical processes.Fig. 4 demonstrates SKA's sensitivity to constrain DM annihilation via the

$ \chi\chi \rightarrow e^{+}e^{-} $ channel is superior to that for other channels such as$ \chi\chi \rightarrow \gamma\gamma $ and$ \chi\chi \rightarrow b\bar{b} $ . Focusing on the optimal annihilation channel$ \chi\chi \rightarrow e^{+}e^{-} $ (upper panel), we find that utilizing the SKA, with 10,000 hours of integration time, the 21 cm power spectrum can achieve a sensitivity of$ \langle\sigma v\rangle \leq 10^{-28}\,{{\rm{cm}}}^{3}\,{{\rm{s}}}^{-1} $ for 10 GeV dark matter particles. This sensitivity surpasses the most stringent current constraints (gray curves), demonstrating SKA's capacity to test existing limits in the near future. Furthermore, the SKA exhibits superior sensitivity to sub-GeV dark matter, a mass range where conventional probing experiments provide only weak constraints. While extended integration would improve sensitivity, practical implementation faces instrumental stability challenges [82].The blue curve in Fig. 4 shows our previous result based on the Hongmeng project, which assessed the capability of constraining DM annihilation parameters using the 21 cm global spectrum. In this work, we compare the results obtained by the SKA with those from Hongmeng. Our analysis reveals that the 21 cm power spectrum exhibits weaker correlations between DM parameters and astrophysical parameters than the 21 cm global spectrum. This reduced degeneracy enables the power spectrum to extract DM-induced signals more effectively. With the same integration time, the SKA achieves higher sensitivity than that implied by the results obtained by Hongmeng with the global spectrum, demonstrating its potential to probe DM annihilation signals beyond the reach of the global spectrum in the near future. Additionally, unlike the 21 cm global spectrum, the 21 cm power spectrum contains information on different scales. Therefore, by probing the 21 cm power spectrum, the SKA is expected to provide insights into the properties of DM by measuring its effects on different scales, thus deepening our understanding of the DM nature.

Furthermore, a comparison between the power spectrum and the global spectrum from the SKA could provide more comprehensive insights. However, a detailed discussion of the Fisher matrix analysis and noise modeling for the global spectrum is beyond the scope of this paper. Therefore, we only present a qualitative analysis here, and defer a more thorough investigation to our upcoming work. Based on our previous work, constraints on DM derived from the global spectrum depend on its measurement error, which comprises two noise components: the foreground residual and the instrumental noise. In this work, the blue curve corresponds to a scenario with 10,000 hours of observation time and a foreground residual level of 0.001. This configuration has already been examined in our previous work, in which the instrumental noise and foreground residual are comparable [21]. Changing the telescope only affects the instrumental noise, while the foreground noise remains unchanged. Assuming the same observational setup, i.e., 10,000 hours and 0.001 foreground residual, we can qualitatively analyze the measurement error of the SKA. Qualitatively, for a fixed integration time, the instrumental noise is approximately inversely proportional to the effective collecting area of the telescope. Given that the SKA has a much larger effective area than the spectrometer employed by the Hongmeng project, its instrumental noise is expected to be significantly lower for the same observation time. Thus, the instrumental noise of the SKA would be lower than the foreground residual, and the total noise would be dominated by the latter. Consequently, under the assumptions of 10,000 hours of integration and 0.001 foreground residual, observations with the SKA are not expected to yield better constraints than those from Hongmeng, which are represented by the blue curves. A more detailed quantitative analysis is beyond the aim of this paper. We plan to carry out a thorough and precise analysis in a forthcoming work.

Fig. 6 indicates that the SKA has superior sensitivity in constraining DM decay via the

$ \chi \rightarrow e^{+}e^{-} $ channel, compared to alternative channels such$ \chi \rightarrow \gamma\gamma $ and$ \chi \rightarrow b\bar{b} $ . Focusing on the optimal decay channel$ \chi \rightarrow e^{+}e^{-} $ (upper panel), and assuming an integration time of 10,000 hours, the SKA is projected to improve constraints on the DM particle decay lifetime by two orders of magnitude, surpassing current experimental bounds (gray curves). This result demonstrates SKA's potential to test existing DM decay models in the near future. While increasing the integration time would further improve sensitivity, practical implementation beyond 10,000 hours may require addressing instrumental stability limitations [82]. Notably, through 21 cm power spectrum measurements, the SKA achieves superior sensitivity to sub-GeV DM, a parameter space weakly constrained by current methods.The blue curve in Fig. 6 represents our previous work, which explored the potential to probe DM decay using the 21 cm global spectrum from the Hongmeng Project. We perform a comparative analysis of DM decay constraints derived from the 21 cm power spectrum and the 21 cm global spectrum. Our analysis reveals less degeneracy between DM decay parameters and astrophysical parameters in the power spectrum compared with the global spectrum. This reduced degeneracy enables the power spectrum to more effectively extract DM-induced signatures. With the same integration time, the 21 cm power spectrum achieves a sensitivity one order of magnitude better than 21 cm global spectrum. This result demonstrates that the SKA will impose tighter constraints on DM decay parameter than those achieved with the 21 cm global spectrum. Furthermore, unlike the global spectrum, the 21 cm power spectrum encodes information across multiple spatial scales, enabling the probing of DM properties at different scales and deepening our understanding of DM’s fundamental nature.

-

The results of the Fisher information matrix analysis are summarized in Figs. 3–6. Figs. 3 and 5 display two representative corner plots that characterize parameter correlations and constraints, assuming a fixed DM particle mass of 100 MeV and an integration time of 10,000 h. The

$ 1\sigma $ and$ 2\sigma $ confidence intervals are represented by the dark and light shaded areas, respectively, whereas the solid curves depict the marginalized posterior distributions. The fiducial model parameters in these figures are consistent with those in Fig. 2. Complete corner plots are provided in Appendix A. Figs. 4 and 6 quantify the projected sensitivity at$ 1\sigma $ confidence level for SKA's capability to probe DM and compare these results with existing constraints at$ 2\sigma $ confidence level from CMB observations [30], gamma ray measurements [45, 49−51, 55, 57, 58], electron-positron pair observations [48, 52, 53], and 21 cm global spectrum measurements [21].

Figure 3. (color online) Fisher forecast for probing DM annihilation through the

$ \chi \chi \rightarrow e^{+} e^{-} $ channel using the 21 cm power spectrum via the SKA.$ 1\sigma $ and$ 2\sigma $ confidence intervals are represented by dark and light shaded areas, respectively, with solid curves indicating the marginalized posteriors. The fiducial model used is consistent with that shown in Fig. 2. The assumed DM particle mass is$ m_{\chi} = 100 $ MeV, integrated over 10,000 h.

Figure 6. (color online) Prospective sensitivity of the SKA for probing the decay of DM particles through three channels. The

$ 1\sigma $ confidence-level sensitivity of the SKA project to the decay lifetime of DM particles (mass range$ 10^{6} $ -$ 10^{12}\,\text{eV} $ ) are shown by the red curves. Existing$ 2\sigma $ upper limits from observations of CMB distortion (black curve) [29, 33], extragalactic photons (gray curves) [41−43, 45, 53, 56, 60], and electron-positron pairs (gray dashed curve) [48, 53] are included for comparison. Prospective sensitivity of the 21 cm global spectrum (blue curve) is also taken into consideration [21].

Figure 5. (color online) Fisher forecast for probing DM decay through the

$ \chi \rightarrow e^{+} e^{-} $ channel using the 21 cm power spectrum by the SKA.$ 1\sigma $ and$ 2\sigma $ confidence intervals are represented by dark and light shaded areas, respectively, with solid curves indicating the marginalized posteriors. The fiducial model used is consistent with that shown in Fig. 2. The assumed DM particle mass is$ m_{\chi} = 100 $ MeV, integrated over 10,000 h.

Figure 4. (color online) Prospective sensitivity of the SKA for probing the annihilation of DM particles through three channels. The

$ 1\sigma $ confidence-level sensitivity of the SKA to the thermally averaged annihilation cross section of DM particles (mass range$ 10^{6} $ −$ 10^{12}\,\text{eV} $ ) are shown by the red curves. Existing$ 2\sigma $ upper limits from observations of CMB distortion (black curve) [30], gamma-ray observations (gray curves) [45, 49−51, 55, 57, 58], and electron-positron pairs (gray dashed curve) [48, 53] are included for comparison. Prospective sensitivity of the 21 cm global spectrum (blue curve) [21] is also included for comparison.Figures 3 and 5 reveal mild correlations between the annihilation and decay parameters of DM particles and the astrophysical parameters. This result indicates a limited degeneracy between the DM-induced exotic energy injection and astrophysical effects on the 21 cm power spectrum. Specifically,

$ \langle \sigma v \rangle $ and τ show weak positive correlations with$ a_{{\rm{esc}}} $ ,$ a_{\star} $ and$ \log_{10} f_{\star} $ , mild negative correlations with$ t_\star $ , and negligible correlations with$ L_{{\rm{X}}} $ and$ f_{{\rm{esc}}} $ . These results demonstrate the feasibility of constraining DM parameters and extracting key properties, particularly thermally averaged annihilation cross section$ \langle \sigma v \rangle $ and decay lifetime τ, using the 21 cm power spectrum. The weak degeneracies demonstrate that the 21 cm power spectrum can effectively constrain DM parameters independently of astrophysical uncertainties. This allows probing of fundamental DM properties, particularly$ \langle \sigma v \rangle $ and τ, with minimized contamination from astrophysical processes.Figure 4 demonstrates that the SKA's sensitivity to constrain DM annihilation via the

$ \chi\chi \rightarrow e^{+}e^{-} $ channel is superior to that for other channels such as$ \chi\chi \rightarrow \gamma\gamma $ and$ \chi\chi \rightarrow b\bar{b} $ . Focusing on the optimal annihilation channel$ \chi\chi \rightarrow e^{+}e^{-} $ (upper panel), we find that utilizing the SKA, with 10,000 h of integration time, the 21 cm power spectrum can achieve a sensitivity of$ \langle\sigma v\rangle \leq 10^{-28}\,{{\rm{cm}}}^{3}\,{{\rm{s}}}^{-1} $ for 10 GeV DM particles. This sensitivity surpasses the most stringent current constraints (gray curves), demonstrating SKA's capacity to test existing limits in the near future. Furthermore, the SKA exhibits superior sensitivity to sub-GeV DM, a mass range where conventional probing experiments provide only weak constraints. While extended integration would improve sensitivity, practical implementation faces instrumental stability challenges [82].The blue curve in Fig. 4 shows our previous result based on the Hongmeng project, which assessed the capability of constraining DM annihilation parameters using the 21 cm global spectrum. In this work, we compare the results obtained using the SKA with those from Hongmeng. Our analysis reveals that the 21 cm power spectrum exhibits weaker correlations between DM parameters and astrophysical parameters than the 21 cm global spectrum. This reduced degeneracy enables the power spectrum to extract DM-induced signals more effectively. With the same integration time, the SKA achieves higher sensitivity than that implied by the results obtained by Hongmeng with the global spectrum, demonstrating its potential to probe DM annihilation signals beyond the reach of the global spectrum in the near future. Additionally, unlike the 21 cm global spectrum, the 21 cm power spectrum contains information on different scales. Therefore, by probing the 21 cm power spectrum, the SKA is expected to provide insights into the properties of DM by measuring its effects on different scales, thus deepening our understanding of the DM nature.

Furthermore, a comparison between the power and global spectra from the SKA can provide more comprehensive insights. However, a detailed discussion of the Fisher matrix analysis and noise modeling for the global spectrum is beyond the scope of this paper. Therefore, we present only a qualitative analysis here and defer a more thorough investigation to our upcoming work. Based on our previous work, constraints on DM derived from the global spectrum depend on its measurement error, which comprises two noise components: the foreground residual and instrumental noise. In this work, the blue curve corresponds to a scenario with 10,000 h of observation time and a foreground residual level of 0.001. This configuration has already been examined in our previous work, in which the instrumental noise and foreground residual are comparable [21]. Changing the telescope affects only the instrumental noise, whereas the foreground noise remains unchanged. Assuming the same observational setup, i.e., 10,000 h and 0.001 foreground residual, we can qualitatively analyze the measurement error of the SKA. Qualitatively, for a fixed integration time, the instrumental noise is approximately inversely proportional to the effective collecting area of the telescope. Because the SKA has a much larger effective area than the spectrometer employed by the Hongmeng project, its instrumental noise is expected to be significantly lower for the same observation time. Thus, the instrumental noise of the SKA would be lower than the foreground residual, and the total noise would be dominated by the latter. Consequently, under the assumptions of 10,000 h of integration and 0.001 foreground residual, observations with the SKA are not expected to yield better constraints than those from Hongmeng, which are represented by the blue curves. A more detailed quantitative analysis is beyond the aim of this paper. We plan to conduct a thorough and precise analysis in a forthcoming work.

Figure 6 indicates that the SKA has superior sensitivity in constraining DM decay via the

$ \chi \rightarrow e^{+}e^{-} $ channel, compared with alternative channels such as$ \chi \rightarrow \gamma\gamma $ and$ \chi \rightarrow b\bar{b} $ . Focusing on the optimal decay channel$ \chi \rightarrow e^{+}e^{-} $ (upper panel), and assuming an integration time of 10,000 h, the SKA is projected to improve constraints on the DM particle decay lifetime by two orders of magnitude, surpassing current experimental bounds (gray curves). This result demonstrates SKA's potential to test existing DM decay models in the near future. While increasing the integration time would further improve sensitivity, practical implementation beyond 10,000 h may require addressing instrumental stability limitations [82]. Notably, through 21 cm power spectrum measurements, the SKA achieves superior sensitivity to sub-GeV DM, a parameter space weakly constrained by current methods.The blue curve in Fig. 6 represents our previous work, which explored the potential to probe DM decay using the 21 cm global spectrum from the Hongmeng Project. We perform a comparative analysis of DM decay constraints derived from the 21 cm power and global spectrums. Our analysis reveals less degeneracy between DM decay and astrophysical parameters in the power spectrum compared with the global spectrum. This reduced degeneracy enables the power spectrum to more effectively extract DM-induced signatures. With the same integration time, the 21 cm power spectrum achieves a sensitivity one order of magnitude better than the 21 cm global spectrum. This result demonstrates that the SKA will impose tighter constraints on DM decay parameters than those achieved with the 21 cm global spectrum. Furthermore, unlike the global spectrum, the 21 cm power spectrum encodes information across multiple spatial scales, enabling the probing of DM properties at different scales and deepening our understanding of DM’s fundamental nature.

-

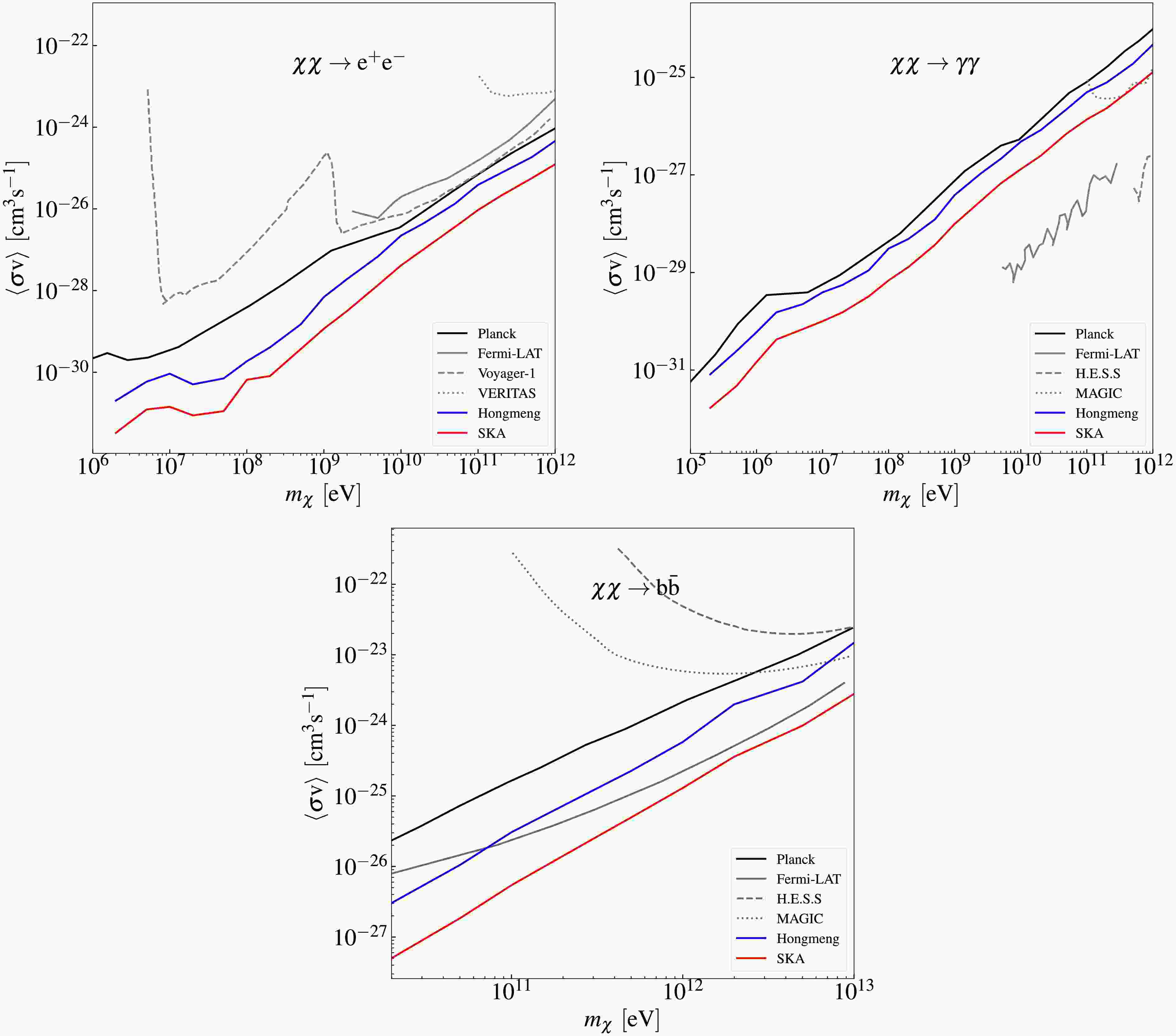

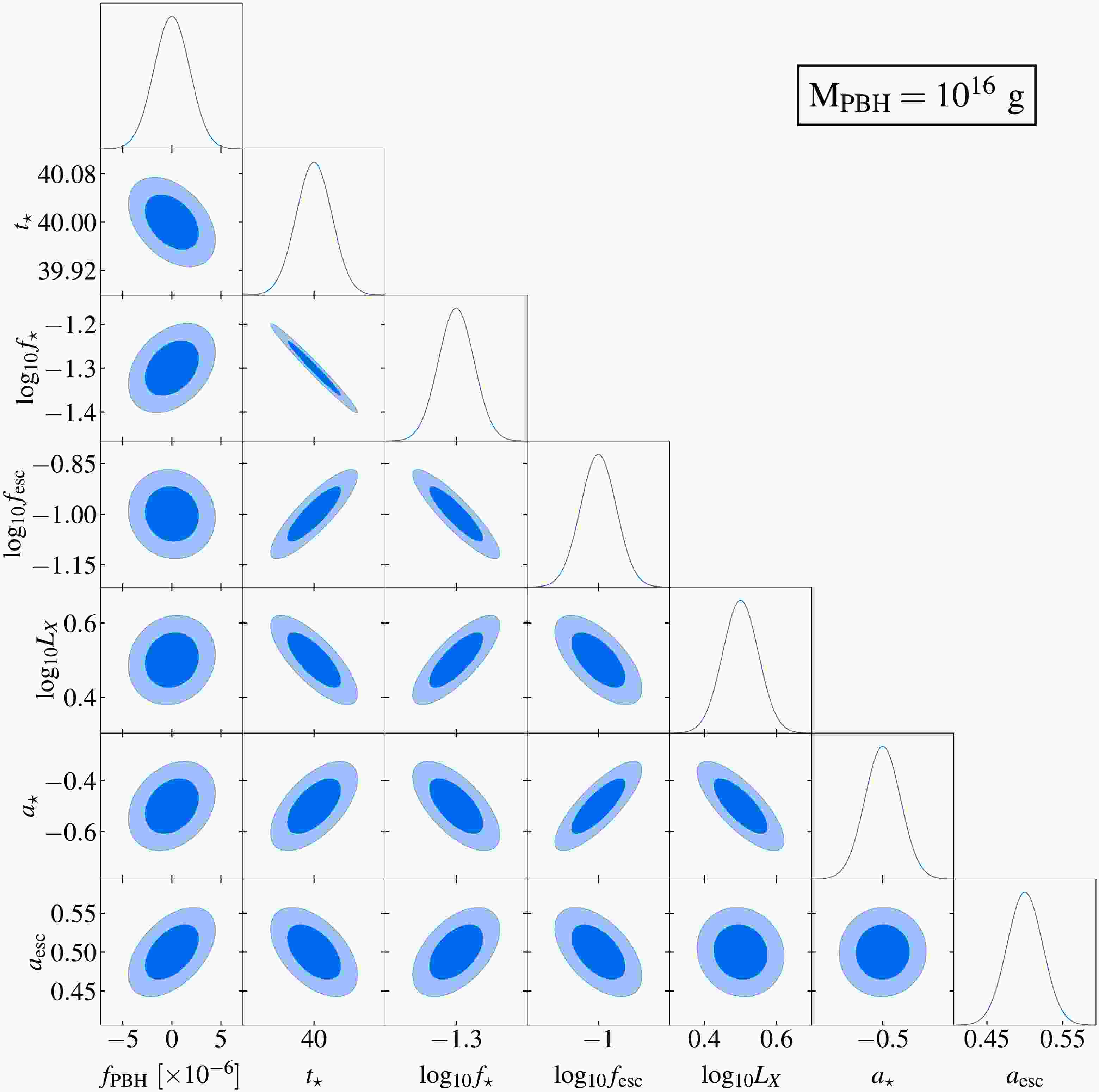

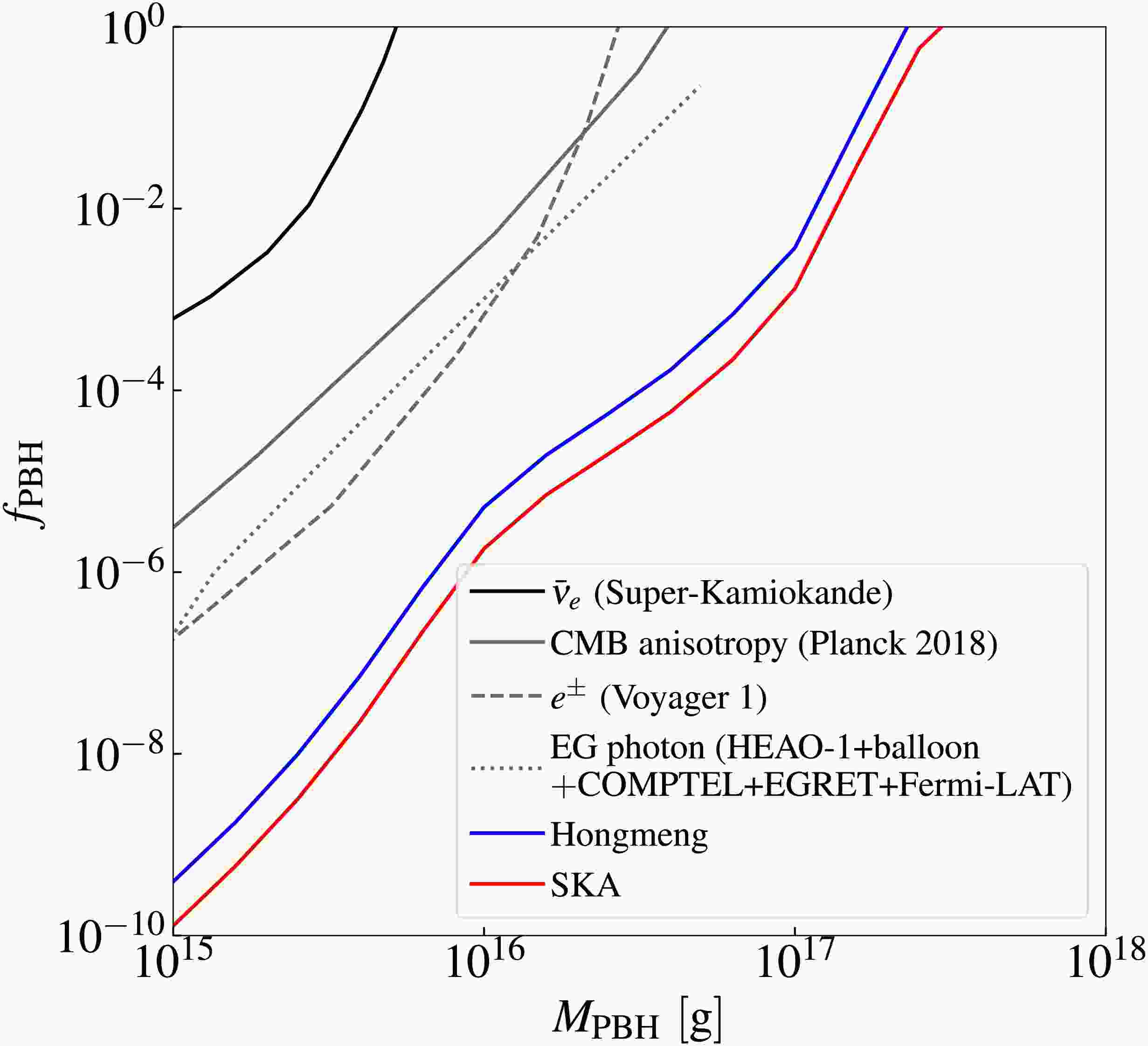

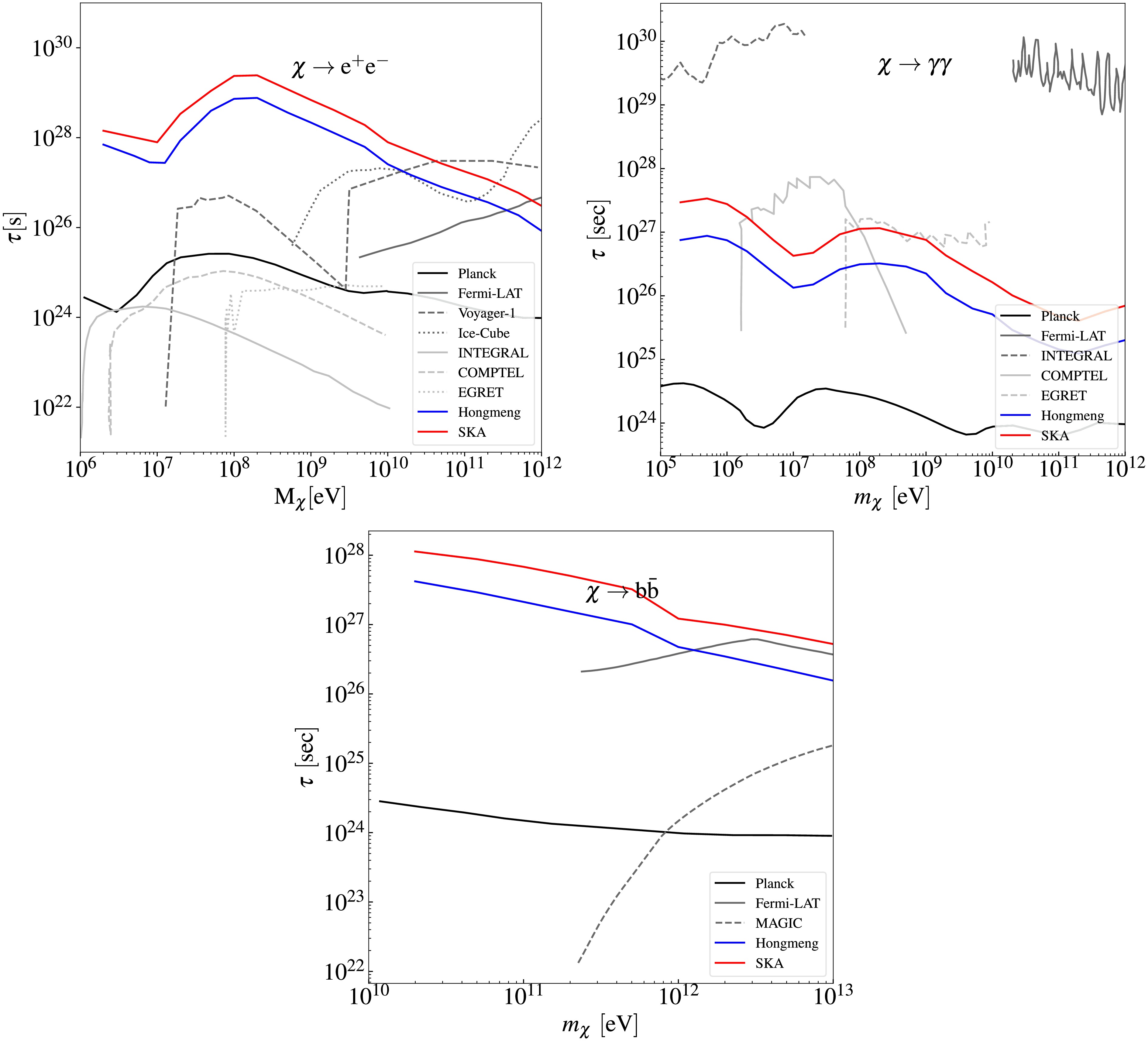

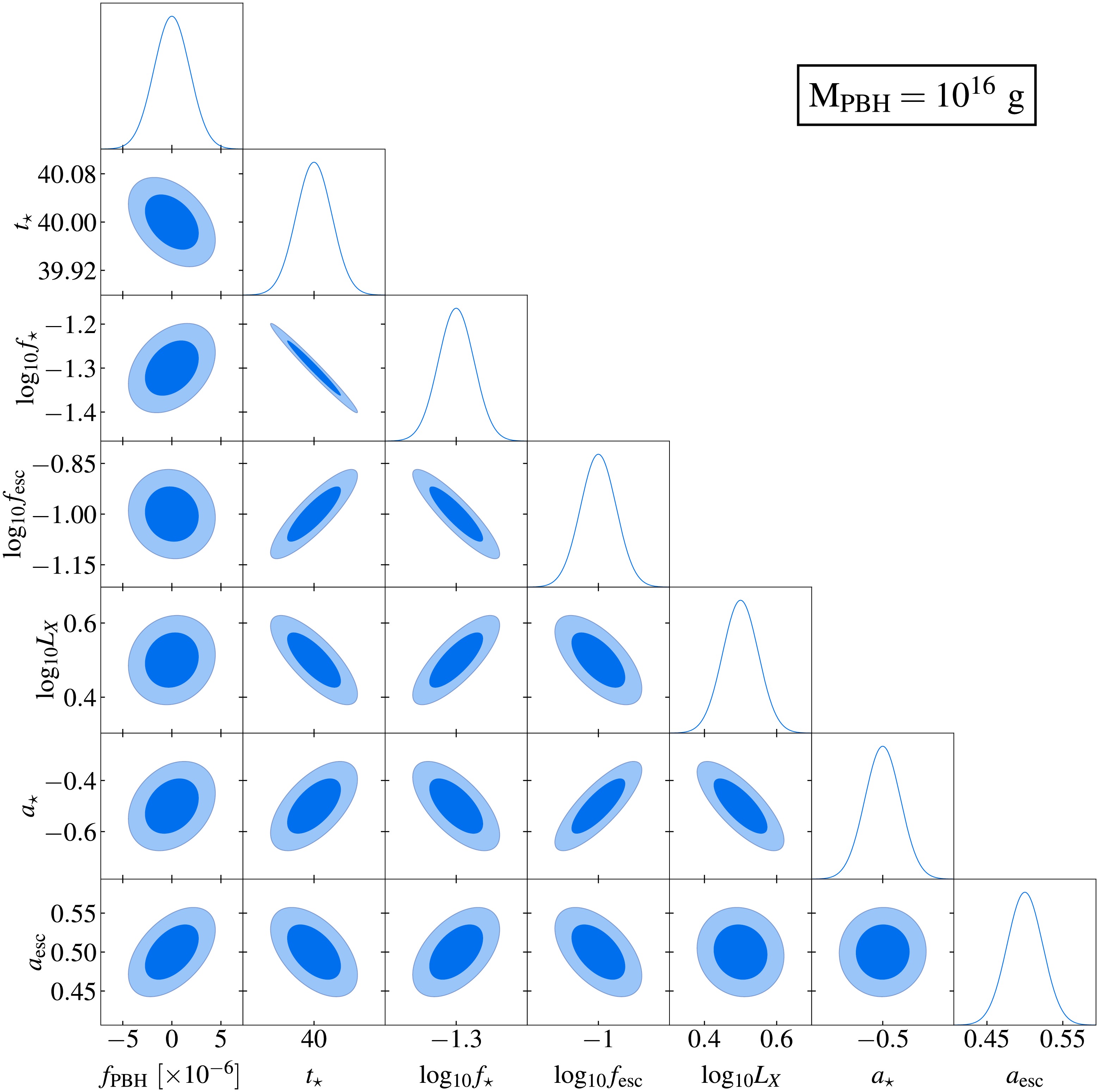

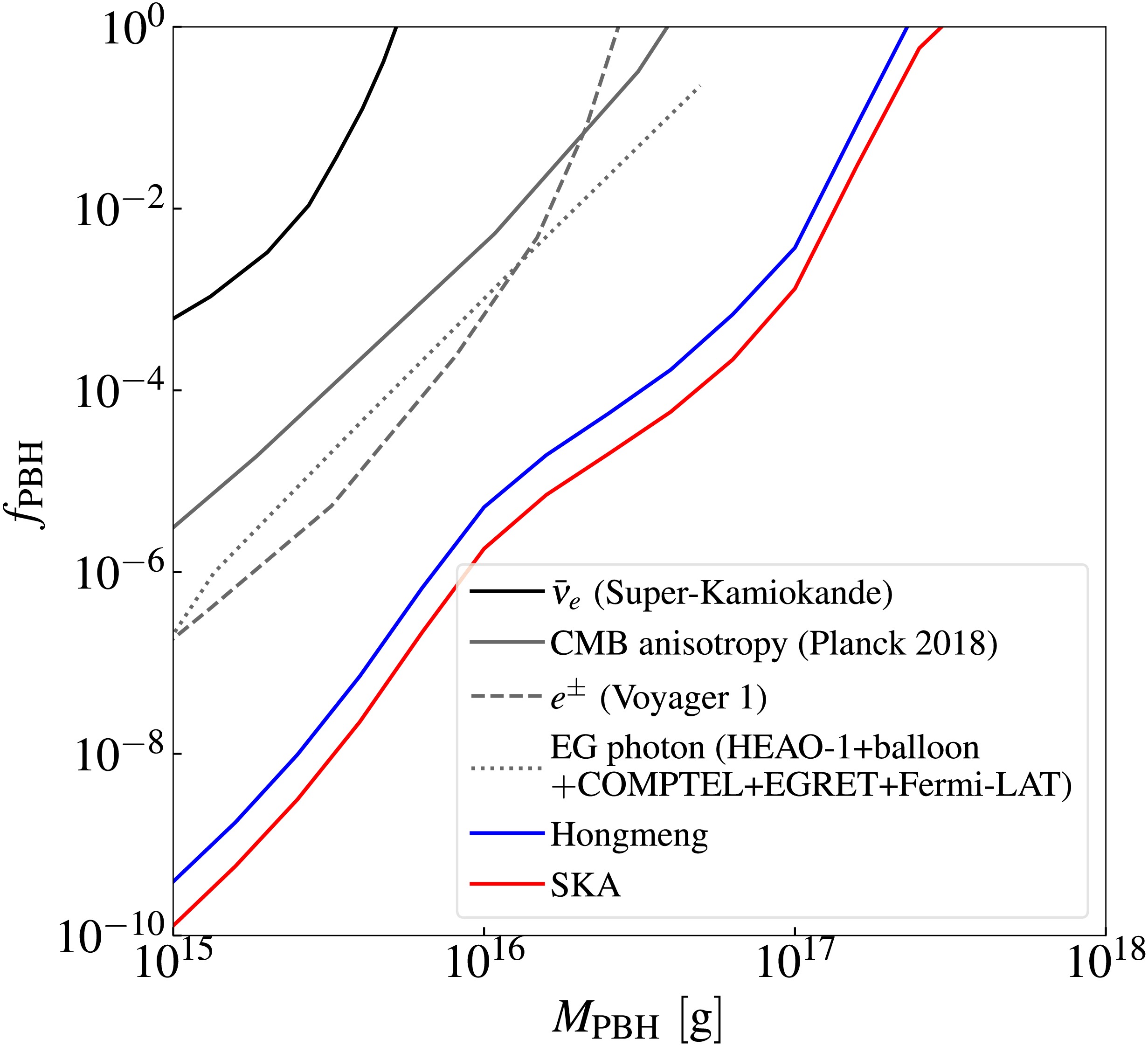

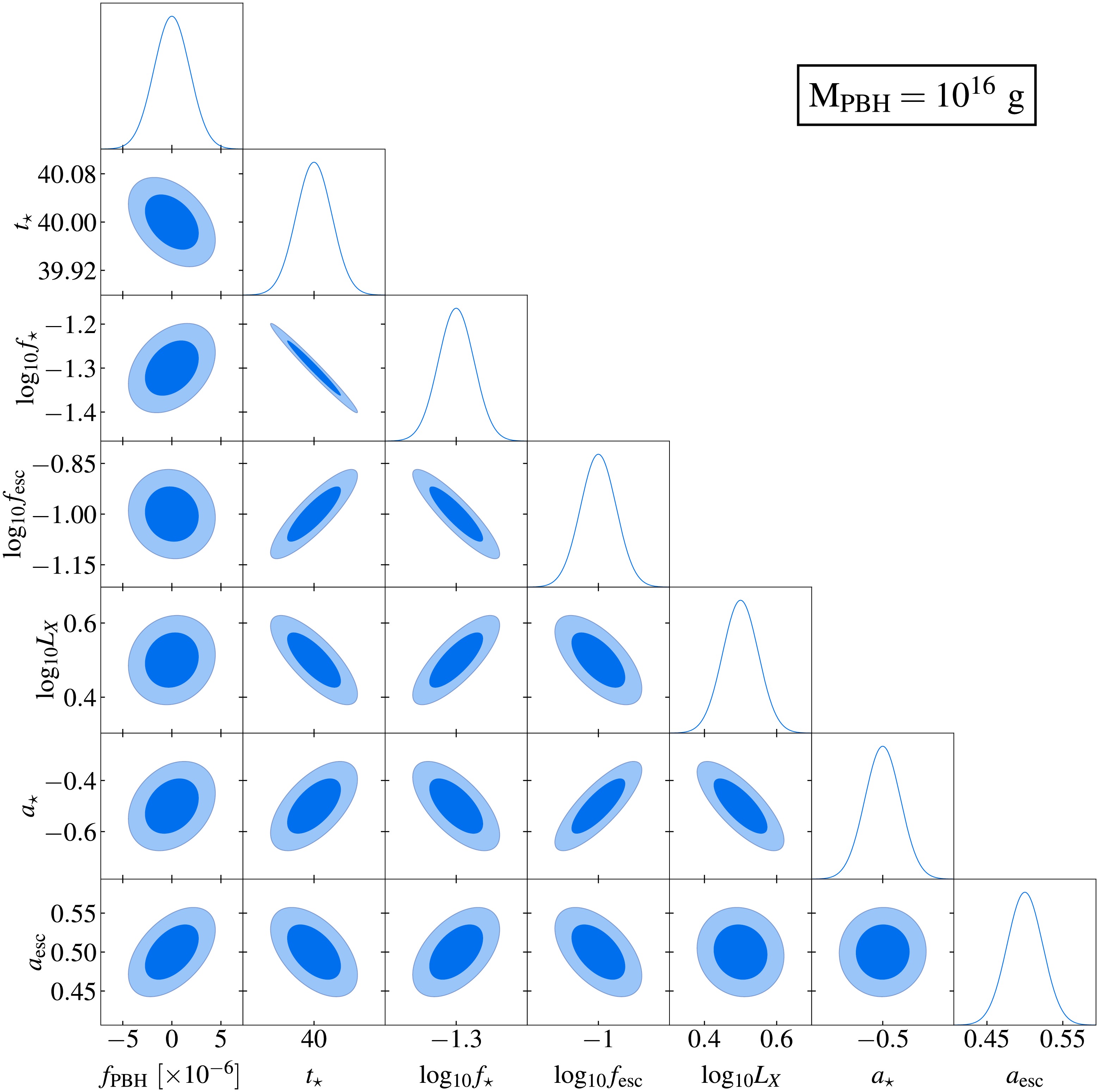

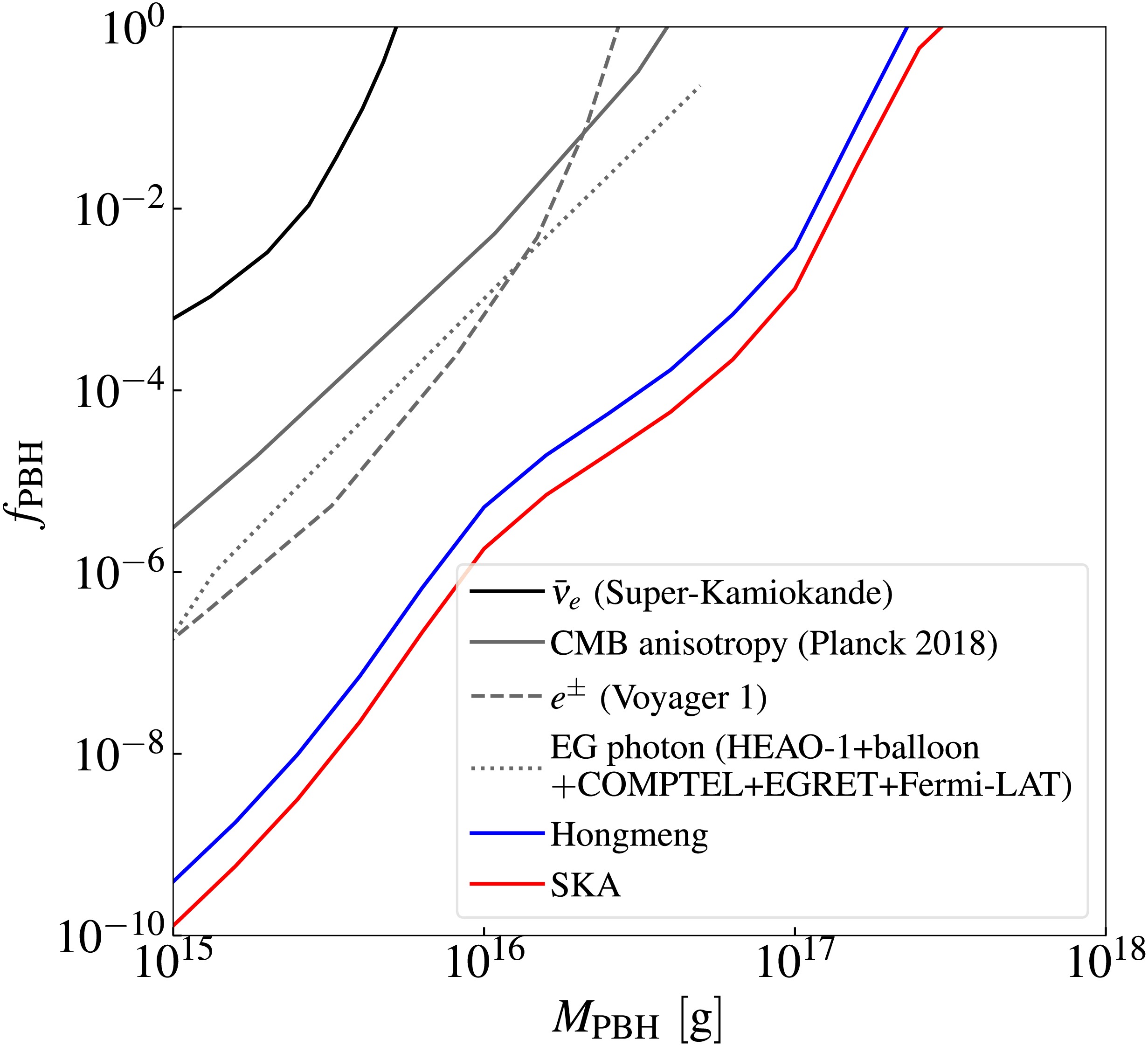

Figs. 7 and 8 summarize the results of our parameter estimation based on Fisher matrix analysis. Fig. 7 shows the correlations and constraints of model parameters for a

$ 10^{16} $ g PBH with an integration time of 10,000 hours. Shaded regions represent the$ 1\sigma $ (dark) and$ 2\sigma $ (light) confidence regions. Corresponding one-dimensional marginalized posterior distributions are shown as solid curves. Fiducial model parameters are consistent with those in Fig. 2. Fig. 8 quantifies the SKA’s sensitivity to Hawking radiation for PBHs with mass ranging from$ 10^{15} $ g to$ 10^{18} $ g, assuming a fixed integration time of 10,000 hours, at the$ 1\sigma $ confidence level. This sensitivity is compared with existing$ 2\sigma $ exclusion bounds from observations of the diffuse neutrino background [46], CMB anisotropy [31, 32, 34], gamma ray measurements [54], electron-positron pair measurements [47, 53], and 21 cm global signals [21].

Figure 7. (color online) Fisher forecast for probing PBH Hawking radiation using the 21 cm power spectrum by the SKA. Dark and light shaded regions correspond to contours at

$ 1\sigma $ and$ 2\sigma $ confidence intervals, respectively. Solid curves represent the marginalized posteriors of the model parameters. Fiducial model used is consistent with that shown in Fig. 2. The mass of PBH is assumed to be$ M_{{\rm{PBH}}} = 10^{16} $ g, with an integration duration of 10,000 hours.

Figure 8. (color online) Prospective sensitivity of the SKA for probing the PBHs. The

$ 1\sigma $ confidence-level sensitivity of the SKA project to measure the abundance of PBHs within the mass range of$ 10^{15}-10^{18} $ g is shown by the red curve. For comparison, we show the existing upper limits at$ 2\sigma $ confidence level from observations of the diffusion neutrino background (black curve) [46], CMB anisotropies (gray solid curve) [31, 32, 34], extra-galactic photons (gray dotted curve) [54], and electron-positron pairs (gray dashed curve) [47]. Prospective sensitivity of the 21 cm global signal (blue curve) is also taken into consideration.Fig. 7 reveals weak correlations between the PBH abundance

$ f_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ and key astrophysical parameters. This result suggests weak degeneracies between the exotic energy injection from the PBH Hawking radiation and astrophysical effects on the 21 cm power spectrum. Specifically,$ f_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ exhibits weak positive correlations with$ a_{{\rm{esc}}} $ ,$ a_{\star} $ , and$ \log_{10}f_{\star} $ , and a negative correlation with$ t_{\star} $ . In contrast,$ f_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ shows no significant correlations with$ L_{{\rm{X}}} $ and$ \log_{10}f_{{\rm{esc}}} $ . These weak degeneracies enable the 21 cm power spectrum to constrain PBH properties while minimizing contamination from astrophysical uncertainties. This result allows the probing of fundamental PBH properties, particularly the abundance$ f_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ .Based on the results in Fig. 8, we demonstrate that the 21 cm power spectrum measured by the SKA achieves a sensitivity to

$ f_{{\rm{PBH}}} \simeq 10^{-10} $ for PBHs with masses of$ 10^{15} $ g, assuming an integration time of 10,000 hours. This result surpasses constraints from existing observations (gray curves) by up to$ 3-4 $ orders of magnitude, indicating that the SKA can test these results in the near future. Moreover, the SKA extends sensitivity to higher-mass PBHs compared with current experiments, particularly probing the unexplored mass range above$ 10^{17} $ g. While extended integration would improve sensitivity, practical operation beyond 10,000 hours may be limited by instrumental stability constraints [82].Our prior analysis using Hongmeng's 21 cm global spectrum also established PBH abundance constraints. Such results are presented by the blue curve in Fig. 8. In this work, we compare the constraints on PBHs derived from the 21 cm power spectrum with those obtained from the 21 cm global spectrum. Our result indicates a weaker coupling of PBH abundance and astrophysical parameters in the 21 cm power spectrum than that in the global spectrum. With the same integration time, the 21 cm power spectrum using the SKA reaches a sensitivity nearly an order of magnitude higher than that achieved by the 21 cm global spectrum with Hongmeng. This result suggests that, in the near future, the SKA is expected to place tighter constraints on PBH abundance than those obtained from the 21 cm global spectrum, thus allowing us to probe PBHs with unprecedented precision.

-

Figures 7 and 8 summarize the results of our parameter estimation based on Fisher matrix analysis. Fig. 7 shows the correlations and constraints of model parameters for a

$ 10^{16} $ g PBH with an integration time of 10,000 h. The shaded regions represent the$ 1\sigma $ (dark) and$ 2\sigma $ (light) confidence regions. The corresponding one-dimensional marginalized posterior distributions are shown as solid curves. The fiducial model parameters are consistent with those in Fig. 2. Figure 8 quantifies the SKA’s sensitivity to Hawking radiation for PBHs with mass ranging from$ 10^{15} $ to$ 10^{18} $ g, assuming a fixed integration time of 10,000 h at the$ 1\sigma $ confidence level. This sensitivity is compared with existing$ 2\sigma $ exclusion bounds from observations of the diffuse neutrino background [46], CMB anisotropy [31, 32, 34], gamma ray measurements [54], electron-positron pair measurements [47, 53], and 21 cm global signals [21].

Figure 7. (color online) Fisher forecast for probing PBH Hawking radiation using the 21 cm power spectrum by the SKA. Dark and light shaded regions correspond to contours at

$ 1\sigma $ and$ 2\sigma $ confidence intervals, respectively. Solid curves represent the marginalized posteriors of the model parameters. The fiducial model used is consistent with that shown in Fig. 2. The mass of PBH is assumed to be$ M_{{\rm{PBH}}} = 10^{16} $ g with an integration duration of 10,000 h.

Figure 8. (color online) Prospective sensitivity of the SKA for probing the PBHs. The

$ 1\sigma $ confidence-level sensitivity of the SKA project to measure the abundance of PBHs within the mass range of$ 10^{15}-10^{18} $ g is shown by the red curve. For comparison, we show the existing upper limits at the$ 2\sigma $ confidence level from observations of the diffusion neutrino background (black curve) [46], CMB anisotropies (gray solid curve) [31, 32, 34], extra-galactic photons (gray dotted curve) [54], and electron-positron pairs (gray dashed curve) [47]. The prospective sensitivity of the 21 cm global signal (blue curve) is also considered.Figure 7 reveals weak correlations between the PBH abundance

$ f_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ and key astrophysical parameters. This result suggests weak degeneracies between the exotic energy injection from the PBH Hawking radiation and astrophysical effects on the 21 cm power spectrum. Specifically,$ f_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ exhibits weak positive correlations with$ a_{{\rm{esc}}} $ ,$ a_{\star} $ , and$ \log_{10}f_{\star} $ , and a negative correlation with$ t_{\star} $ . In contrast,$ f_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ shows no significant correlations with$ L_{{\rm{X}}} $ and$ \log_{10}f_{{\rm{esc}}} $ . These weak degeneracies enable the 21 cm power spectrum to constrain PBH properties while minimizing contamination from astrophysical uncertainties. This result allows the probing of fundamental PBH properties, particularly the abundance$ f_{{\rm{PBH}}} $ .Based on the results in Fig. 8, we demonstrate that the 21 cm power spectrum measured by the SKA achieves a sensitivity to