-

The study of nuclear properties under extreme conditions has long been a focal point of research [1]. These studies are crucial for understanding astrophysical and nuclear physics-related issues [2−4]. The heavy-ion collisions at intermediate energies are commonly used to study thermodynamic properties of the thermal nuclei at high temperature and density [5−7]. Thereinto, the hot nuclear system with excitation energy in the range of 3-8 MeV/A is applied to study the nuclear liquid-gas phase transition [8, 9]. Pochodzalla et al. used Au + Au peripheral collisions to analyze the caloric curve and discovered a plateau in the nuclear temperature in the excitation-energy-region of 3-8 MeV/A, a phenomenon similar to the liquid-gas phase transition of water at 373.15 K. This finding is considered significant evidence of the liquid-gas phase transition in nuclei [10].

Isospin effects play a critical role in nuclear fragmentation reactions [11−13]. Research on isospin effects provides a new way to extract information on symmetry energy [14, 15]. Since the application of the concept of the caloric curve to atomic nuclei, a significant isotopic dependence of the caloric curve or the nuclear temperatures is expected [16, 17]. Related experiments have been explored. An example is the comprehensive study of the isospin dependence of projectile fragmentation in 107Sn, 124Sn, 124La + Sn at 600 MeV/nucleon at the GSI Schwerionen-Synchrotron. In 2009, the A/Z dependence of projectile fragmentation at relativistic energies was studied with the ALADIN forward spectrometer at SIS [18]. It is found that the isotope temperatures for the neutron-rich projectiles are slightly larger than those for the neutron-poor projectiles. Global fragmentation observables were published, showing the weak dependence on the projectile N/Z [19]. Based on the Z distributions of the largest fragment in spectator fragmentation, the deduced pseudocritical points are found to be only weakly dependent on the ratio of the fragmenting spectator source [20]. Recently, the Large-Area-Neutron-Detector LAND is used to measure the neutron emission in projectile fragmentation and explore the N/Z dependence of the identified neutron source [21].

For the interpretation of the data, various models have been developed to study the mechanisms of the fragmentation reaction [22]. Statistical models are based on the assumption that fragments produced in a collision arise from a system in thermal equilibrium, and have been applied widely to study the fragmentation. In 1999, Borderie et al. [23] used a quantum statistical model based on the thermodynamic equilibrium to describe the properties of fragment products from the projectile in an Ar+Ni reaction with an incident energy of 95 MeV/A. Similarly, Ogul et al. [19] applied the statistical multifragmentation model to study the spectator fragment products and found that the model could effectively describe the distribution of spectator fragmentation products. However, many studies suggest that thermal nuclei produced in peripheral collisions only partially achieve thermodynamic equilibrium. In 2003, Colin et al. [24] studied the fragmentation process of spectators in heavy-ion collisions in the Fermi energy region using systems of different masses. They found that most of the spectator fragments did not satisfy thermodynamic equilibrium conditions. Zbiri et al. [25] used Au + Au collisions in the intermediate-energy region and studied the fragmentation products from both participants and spectators, and showed that the spectator fragmentation products did not achieve equilibrium in the dynamical degrees of freedom. Furthermore, Russotto et al. [26, 27], using heavy-ion collisions in the Fermi energy region, studied the emission probabilities of intermediate-mass fragments and found that the emission of these fragments involved both dynamical and statistical mechanisms.

On the other hand, dynamical models, such as the Isospin-dependent Quantum Molecular Dynamics (IQMD) model, focus on the microscopic dynamics of the collision and fragmentation process, considering factors such as nucleon-nucleon interactions and the evolution of the system in time [28]. Hybrid models combining dynamic simulations (e.g., EQMD, UrQMD) with statistical decay codes (e.g., GEMINI) extend simulation timescales and improve agreement with experimental data, particularly for light cluster yields and collective observables like flow and stopping power [29, 30]. The IQMD+GEMINI framework has advanced nuclear reaction modeling by improving cross-section predictions through Bayesian neural network tuning and enabling studies of phase transitions via higher-order fragment charge fluctuations [31−33]. However, it still exhibits limitations in accurately predicting yields for extremely neutron-deficient nuclei and struggles to fully capture shell effects and multifragmentation processes [33]. The combination of microscopic dynamics and the statistical model allows for a more comprehensive description of the fragmentation process, including the transition from a dynamical to a statistical regime as the system evolves. Recent progress has been made in combining these models to better predict and describe the complex fragmentation patterns observed in peripheral collisions. For instance, in the works by Su et al., the IQMD model is used to study the non-equilibrium thermalization and fragmentation. The statistical code GEMINI is applied to simulate the second decay of the pre-fragments. The data about the intermediate-mass fragments (IMFs) in 107,124Sn and 124La projectile fragmentation have been successfully reproduced by the combining model [34−36].

In this work, the IQMD+GEMINI model is applied to study the properties of neutrons emitted from the spectator source produced in 124Sn,107Sn + 120Sn collisions at 600 MeV/nucleon. The paper is organized as follows. In Sec. II, we briefly describe the method. In Sec. III, we present both the results and discussions. Finally, a summary is given in Sec. IV.

-

The study of nuclear properties under extreme conditions has long been a focal point of research [1]. Such studies are crucial for understanding astrophysical and nuclear physics-related issues [2−4]. The heavy-ion collisions at intermediate energies are commonly used to study thermodynamic properties of the thermal nuclei at high temperature and density [5−7]. Moreover, a hot nuclear system with excitation energy in the 3−8 MeV/A range has been applied to study the nuclear liquid-gas phase transition [8, 9]. Pochodzalla et al. used Au + Au peripheral collisions to analyze the caloric curve and discovered a plateau in the nuclear temperature in the excitation-energy-region of 3−8 MeV/A, a phenomenon similar to the liquid-gas phase transition of water at 373.15 K. This finding is considered significant evidence of the liquid-gas phase transition in nuclei [10].

Isospin effects play a critical role in nuclear fragmentation reactions [11−13]. Research on isospin effects provides a new way to extract information on symmetry energy [14, 15]. Since the application of the caloric curve concept to atomic nuclei, a significant isotopic dependence of the caloric curve or the nuclear temperatures is expected [16, 17]. Related experiments have been explored. An example is the comprehensive study of the isospin dependence of projectile fragmentation in 107Sn, 124Sn, 124La + Sn at 600 MeV/nucleon at the GSI Schwerionen-Synchrotron. In 2009, the A/Z dependence of projectile fragmentation at relativistic energies was studied with the ALADIN forward spectrometer at SIS [18]. It was found that the isotope temperatures for the neutron-rich projectiles are slightly larger than those for the neutron-poor projectiles. Global fragmentation observables have been published, showing the weak dependence on the projectile N/Z [19]. Based on the Z distributions of the largest fragment in spectator fragmentation, the deduced pseudocritical points were found to be only weakly dependent on the ratio of the fragmenting spectator source [20]. Recently, the Large-Area-Neutron-Detector LAND has been used to measure the neutron emission in projectile fragmentation and explore the N/Z dependence of the identified neutron source [21].

For data interpretation, various models have been developed to study the mechanisms of fragmentation reactions [22]. Statistical models are based on the assumption that fragments produced in a collision arise from a system in thermal equilibrium, and they have been applied widely to study fragmentation. In 1999, Borderie et al. [23] used a quantum statistical model based on the thermodynamic equilibrium to describe the properties of fragment products from the projectile in an Ar+Ni reaction with an incident energy of 95 MeV/A. Similarly, Ogul et al. [19] applied the statistical multifragmentation model to study the spectator fragment products and found that the model could effectively describe the distribution of spectator fragmentation products. However, many studies suggest that thermal nuclei produced in peripheral collisions only partially achieve thermodynamic equilibrium. In 2003, Colin et al. [24] studied the fragmentation process of spectators in heavy-ion collisions in the Fermi energy region using systems of different masses. They found that most of the spectator fragments did not satisfy thermodynamic equilibrium conditions. Zbiri et al. [25] used Au + Au collisions in the intermediate-energy region and studied the fragmentation products from both participants and spectators, and showed that the spectator fragmentation products did not achieve equilibrium in the dynamic degrees of freedom. Furthermore, Russotto et al. [26, 27], using heavy-ion collisions in the Fermi energy region, studied the emission probabilities of intermediate-mass fragments and found that the emission of these fragments involved both dynamical and statistical mechanisms.

By contrast, dynamical models, such as the Isospin-dependent Quantum Molecular Dynamics (IQMD) model, focus on the microscopic dynamics of the collision and fragmentation process, considering factors such as nucleon-nucleon interactions and the evolution of the system in time [28]. Hybrid models combining dynamic simulations ( e.g., EQMD, UrQMD) with statistical decay codes ( e.g., GEMINI) extend simulation timescales and improve agreement with experimental data, particularly for light cluster yields and collective observables like flow and stopping power [29, 30]. The IQMD+ GEMINI framework has advanced nuclear reaction modeling by improving cross-section predictions through Bayesian neural network tuning and enabling studies of phase transitions via higher-order fragment charge fluctuations [31−33]. However, it still exhibits limitations in accurately predicting yields for extremely neutron-deficient nuclei and struggles to fully capture shell effects and multifragmentation processes [33]. The combination of microscopic dynamics and statistical models allows for a more comprehensive description of the fragmentation process, including the transition from a dynamical to a statistical regime as the system evolves. Recently, progress has been made in combining these models to better predict and describe the complex fragmentation patterns observed in peripheral collisions. For instance, Su et al. used the IQMD model to study non-equilibrium thermalization and fragmentation. The statistical code GEMINI was applied to simulate the secondary decay of the pre-fragments. The combined model has been used to successfully reporduce data about the intermediate-mass fragments (IMFs) in 107,124Sn and 124La projectile fragmentation [34−36].

In this work, the IQMD+GEMINI model is applied to study the properties of neutrons emitted from the spectator source produced in 124Sn,107Sn + 120Sn collisions at 600 MeV/nucleon. The paper is organized as follows. In Sec. II, we briefly describe the method. In Sec. III, we present both the results and discussions. Finally, a summary is given in Sec. IV.

-

The wave function for each nucleon in the IQMD model is represented by a Gaussian wave packet

$ \begin{aligned} \phi_i({\bf{r}},t) = \frac{1}{(2\pi L)^{3/4}} e^{-\frac{[{\bf{r}}-{\bf{r}}_{i}(t)]^2}{4L}} e^{ \frac{i{\bf{r}}\cdot{\bf{p}}_{i}(t)}{\hbar}}, \end{aligned} $

(1) where

$ {\bf{r}}_{i} $ and$ {\bf{p}}_{i} $ are the average values of the positions and momenta of the ith nucleon, and$ L $ is related to the extension of the wave packet. The phase-space density of the system is given by$ \begin{aligned} f({\bf{r}},{\bf{p}},t) = \sum_{i=1}^{N}\frac{1}{(\pi\hbar)^3} e^{{-\frac{[{\bf{r}}-{\bf{r}}_{i}(t)]^2}{2L}}} e^{{-\frac{[{\bf{p}}-{\bf{p}}_{i}(t)]^2 \cdot 2L}{\hbar^2}}}. \end{aligned} $

(2) The time evolution of the nucleons in the system are governed by Hamiltonian equations of motion,

$ \begin{aligned}[b] &\dot{{\bf{r}}}_{i} = \nabla_{{\bf{p}}_{i}} H , \\ &\dot{{\bf{p}}}_{i} = -\nabla_{{\bf{r}}_{i}} H . \end{aligned} $

(3) The Hamiltonian of baryons consists of the kinetic energy, the Coulomb interaction, and the nuclear interaction. The nuclear interaction includes the local two-body and three-body interactions, the symmetry potential. The nuclear potential density is expressed as

$ \begin{aligned} \begin{aligned} V(\rho, \delta) = & \frac{\alpha}{2} \frac{\rho^2}{\rho_0} + \frac{\beta}{\gamma+1} \frac{\rho^{\gamma+1}}{\rho_0^{\gamma}} + \frac{C_{sp}}{2}(\frac{\rho}{\rho_{0}})^{\gamma_{i}} \rho \delta ^{2}, \end{aligned} \end{aligned} $

(4) where

$ \rho_0 $ is the normal density. The parameters used in the following work are$ \alpha $ = -356.00 MeV,$ \beta $ = 303.00 MeV,$ \gamma $ = 7/6,$ C_{sp} $ = 38.06 MeV and$ \gamma_{i} $ = 0.75.Binary NN collisions are included. The elastic proton-proton scatterings, elastic neutron-neutron scatterings, elastic neutron-proton scatterings, and inelastic NN collisions are included. The parametrization of the differential cross sections in free space are taken from Ref. [37]. The in-medium factor of elastic cross sections is considered as

$ \begin{aligned}[b]] {f_{el}^ {med} } &=\sigma _{0}/\sigma^{free}\tan h(\sigma^{free}/\sigma _{0}),\\ \sigma _{0}&=0.85\rho ^{-2/3} . \end{aligned} $

(5) The dependence of density can be seen in Eq. (5). The cross sections in free space depends on the energy and isospin, so the in-medium factor is also governed by energy and isospin.

The method of the phase space density constraint (PSDC) is taken into account. The Pauli blocking method related to the PSDC is necessary after we use the PSDC method to compensate for the fermionic feature. The phase-space occupation probability

$ \overline{{f}_i} $ is calculated by performing the integration on a hypercube of volume$ {h}^3 $ in the phase space centered around the$ {i} $ th nucleon at each time step, i.e.$ \begin{aligned} \bar{f}_i =0.621+\sum_{j\ne 1}^{N} \frac{\delta _{\tau _j,\tau _i}}{2} \int_{h^3}\frac{1}{\pi ^3\hbar ^3}e^{-\frac{(r_j-r_i)^2}{2L}- \frac{(p_j-p_i)^2}{\hbar ^2/2L}}d^3rd^3p. \end{aligned} $

(6) Here 0.621 is the contribution itself and

$ \tau _i $ represents isospin degree of freedom. At each time step, the phase-space occupation$ \overline{{f}_i} $ for each nucleon is checked. If phase-space occupation$ \overline{{f}_i} $ has a value greater than 1, the momentum of the$ {i} $ th nucleon is changed randomly by the many-body elastic scattering. Meanwhile, the Pauli blocking in the binary NN collisions is modified. Only if$ \overline{{f}_i} $ and$ \overline{{f}_j} $ at the final states are both less than 1, the many-body elastic scattering is accepted. -

The wave function for each nucleon in the IQMD model is represented by a Gaussian wave packet

$ \begin{aligned} \phi_i({\bf{r}},t) = \frac{1}{(2\pi L)^{3/4}} {\rm e}^{-\frac{[{\bf{r}}-{\bf{r}}_{i}(t)]^2}{4L}} {\rm e}^{ \frac{{\rm i}{\bf{r}}\cdot{\bf{p}}_{i}(t)}{\hbar}}, \end{aligned} $

(1) where

$ {\bf{r}}_{i} $ and$ {\bf{p}}_{i} $ are the average values of the positions and momenta of the ith nucleon, and$ L $ is related to the extension of the wave packet. The phase-space density of the system is given by$ \begin{aligned} f({\bf{r}},{\bf{p}},t) = \sum_{i=1}^{N}\frac{1}{(\pi\hbar)^3} {\rm e}^{{-\frac{[{\bf{r}}-{\bf{r}}_{i}(t)]^2}{2L}}} {\rm e}^{{-\frac{[{\bf{p}}-{\bf{p}}_{i}(t)]^2 \cdot 2L}{\hbar^2}}}. \end{aligned} $

(2) The time evolution of the nucleons in the system is governed by Hamiltonian equations of motion:

$ \begin{aligned}[b] &\dot{{\bf{r}}}_{i} = \nabla_{{\bf{p}}_{i}} H , \\ &\dot{{\bf{p}}}_{i} = -\nabla_{{\bf{r}}_{i}} H . \end{aligned} $

(3) The Hamiltonian of baryons consists of kinetic energy, Coulomb interaction, and nuclear interaction. The nuclear interaction includes the local two-body and three-body interactions, the symmetry potential. The nuclear potential density is expressed as

$ \begin{aligned} \begin{aligned} V(\rho, \delta) = & \frac{\alpha}{2} \frac{\rho^2}{\rho_0} + \frac{\beta}{\gamma+1} \frac{\rho^{\gamma+1}}{\rho_0^{\gamma}} + \frac{C_{sp}}{2}(\frac{\rho}{\rho_{0}})^{\gamma_{i}} \rho \delta ^{2}, \end{aligned} \end{aligned} $

(4) where

$ \rho_0 $ is the normal density. Subsequently, the following parameters are used:$ \alpha $ = -356.00 MeV,$ \beta $ = 303.00 MeV,$ \gamma $ = 7/6,$ C_{sp} $ = 38.06 MeV and$ \gamma_{i} $ = 0.75.Binary NN collisions are included. The elastic proton-proton scatterings, elastic neutron-neutron scatterings, elastic neutron-proton scatterings, and inelastic NN collisions are included. The parametrization of the differential cross sections in free space are taken from Ref. [37]. The in-medium factor of elastic cross sections is considered as

$ \begin{aligned}[b]] {f_{el}^ {\rm med} } &=\sigma _{0}/\sigma^{\rm free}\tan h(\sigma^{\rm free}/\sigma _{0}),\\ \sigma _{0}&=0.85\rho ^{-2/3} . \end{aligned} $

(5) The dependence of density can be seen in Eq. (5). The cross sections in free space depend on the energy and isospin; thus, the in-medium factor is also governed by energy and isospin.

The method of the phase space density constraint (PSDC) is taken into account. The Pauli blocking method related to the PSDC is necessary after we use the PSDC method to compensate for the fermionic feature. The phase-space occupation probability

$ \overline{{f}_i} $ is calculated by performing the integration on a hypercube of volume$ {h}^3 $ in the phase space centered around the$ {i} $ th nucleon at each time step, i.e.,$ \begin{aligned} \bar{f}_i =0.621+\sum_{j\ne 1}^{N} \frac{\delta _{\tau _j,\tau _i}}{2} \int_{h^3}\frac{1}{\pi ^3\hbar ^3}{\rm e}^{-\frac{(r_j-r_i)^2}{2L}- \frac{(p_j-p_i)^2}{\hbar ^2/2L}}{\rm d}^3r{\rm d}^3p. \end{aligned} $

(6) Here, 0.621 is the contribution itself, and

$ \tau _i $ represents the isospin degree of freedom. At each time step, the phase-space occupation$ \overline{{f}_i} $ for each nucleon is checked. If phase-space occupation$ \overline{{f}_i} $ has a value greater than 1, the momentum of the$ {i} $ th nucleon is changed randomly by the many-body elastic scattering. Meanwhile, the Pauli blocking in the binary NN collisions is modified. Only if$ \overline{{f}_i} $ and$ \overline{{f}_j} $ at the final states are both less than 1, the many-body elastic scattering is accepted. -

The IQMD code outputs hot fragments. To obtain cold fragments, light particles (Z

$ < $ 3) from the hot fragments are emitted using the statistical code GEMINI [38]. A Monte Carlo technique is employed to follow the decay chains until the excitation energy of the product is zero. The partial decay widths are taken from the Hauser-Feshbach formalism:$ \begin{aligned}[b] \Gamma_{J_{2}}(Z_{1}, A_{1}, Z_{2}, A_{2}) =\;& \frac{2J_{1}+1}{2\pi \rho_{0}} \sum_{l = |J_{0}-J_{2}|}^{J_{0}+J_{2}} \int_{0}^{E^{*}-B-E_{\rm rot}}\\&\times T_{l}(\varepsilon) \rho_{2}(E^{*}-B-E_{\rm rot}-\varepsilon, J_{2}) {\rm d}\varepsilon \end{aligned}, $

(7) where

$ l $ and$ \varepsilon $ are the orbital angular momentum and kinetic energy of the emitted particle, E$ _{\rm rot} $ is the rotation plus deformation energy of the residual system,$ \rho_{0} $ and$ \rho_{2} $ are the level densities of the initial and residual systems, respectively, and T$ _{l} $ is the transmission coefficient. -

The output of the IQMD code are the hot fragments. In order to obtain the cold fragments, emission of lightparticles (Z

$ < $ 3) from hot fragments is performed by the statistical code GEMINI [38]. A Monte Carlo technique is employed to follow the decay chains until the excitation energy of the product is zero. The partial decay widths are taken from the Hauser-Feshbach formalism,$ \begin{aligned}[b] \Gamma_{J_{2}}(Z_{1}, A_{1}, Z_{2}, A_{2}) =\;& \frac{2J_{1}+1}{2\pi \rho_{0}} \sum_{l = |J_{0}-J_{2}|}^{J_{0}+J_{2}} \int_{0}^{E^{*}-B-E_{rot}}\\&\times T_{l}(\varepsilon) \rho_{2}(E^{*}-B-E_{rot}-\varepsilon, J_{2}) d\varepsilon \end{aligned} $

(7) where

$ l $ and$ \varepsilon $ are the orbital angular momentum and kinetic energy of the emitted particle, E$ _{rot} $ is the rotation plus deformation energy of the residual system,$ \rho_{0} $ and$ \rho_{2} $ are the level densities of the initial and residual systems, respectively, and T$ _{l} $ is the transmission coefficient. -

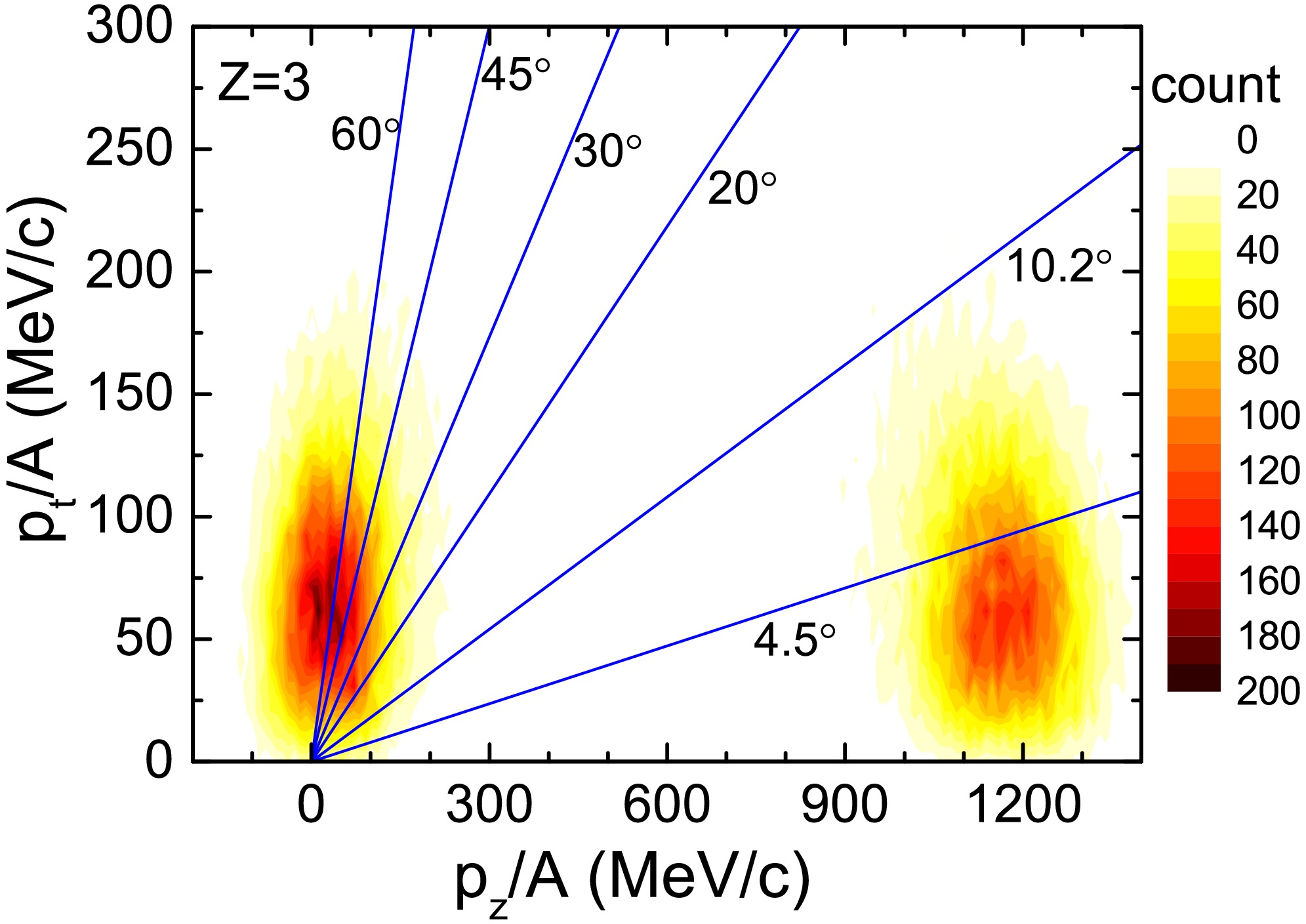

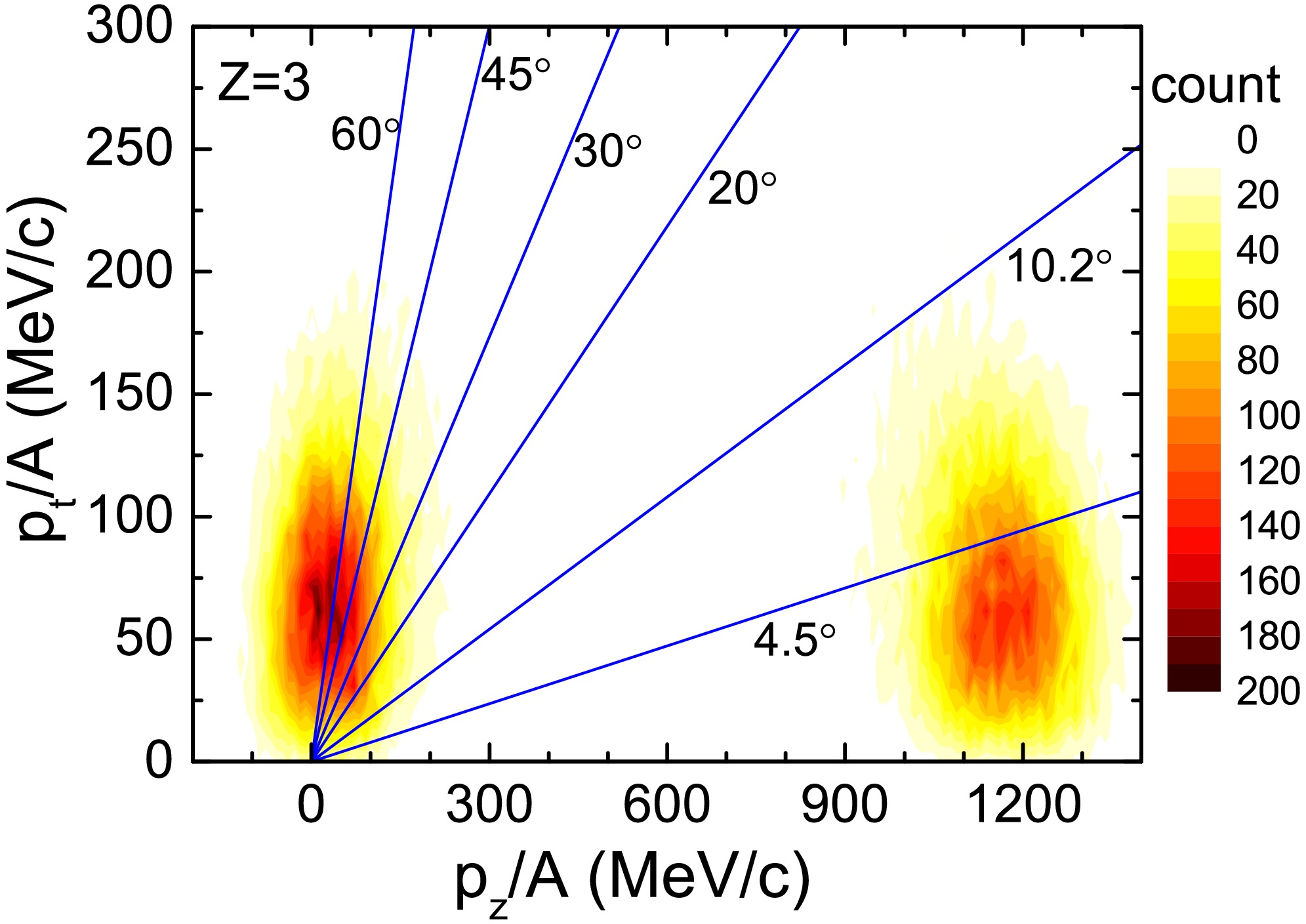

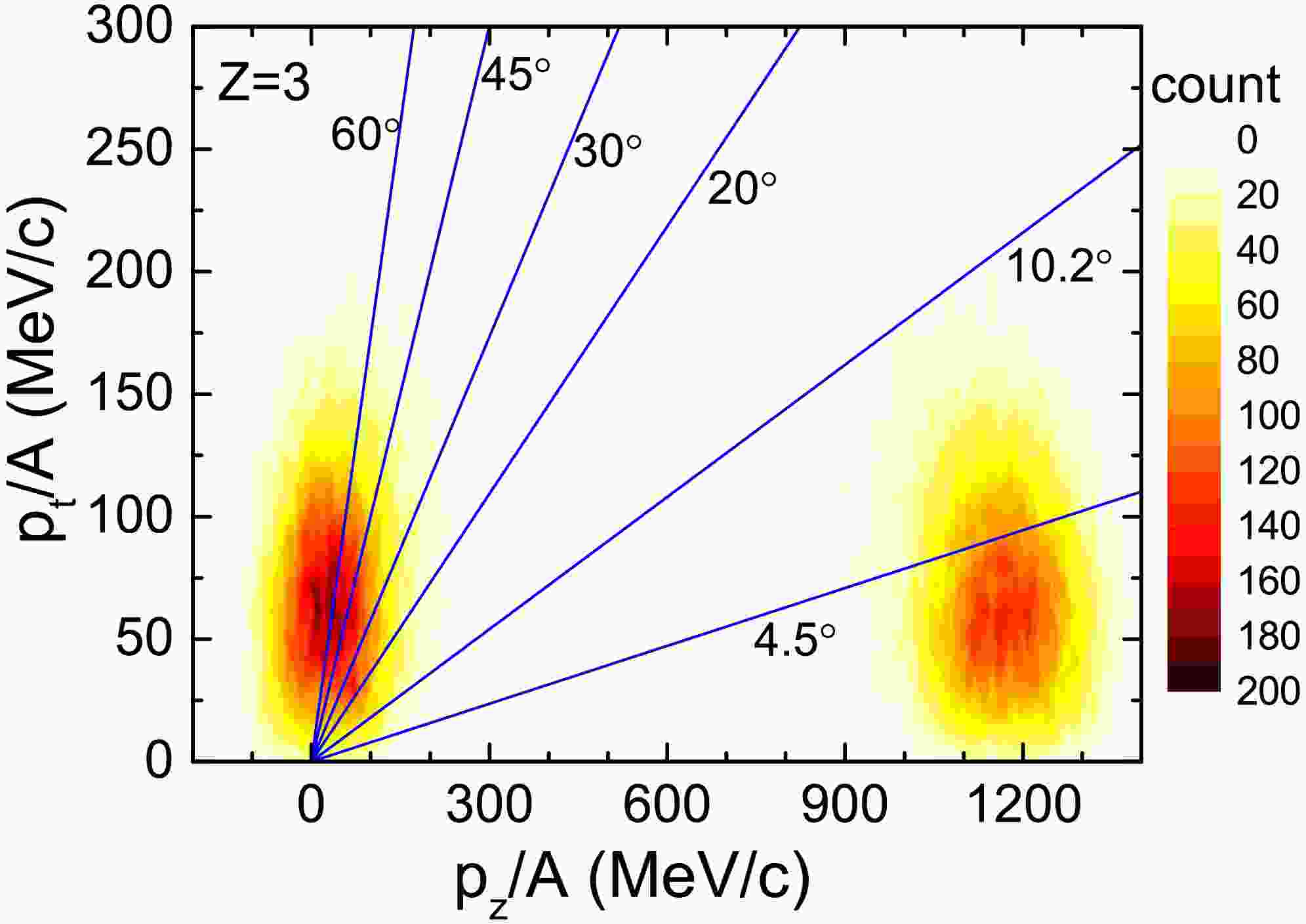

The 107,124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon is simulated by the IQMD+GEMINI model. The fragments with Z = 3 and neutrons are applied to extract the fragmenting source. Figure 1 shows the two-dimensional distribution of transverse and longitudinal momentum for Z = 3 fragments. Two distinct emission sources are apparent in the figure: a target-like source around

$ p_z $ = 0 and a spectator source near$ p_z $ = 1200 MeV/c. The distribution's hot spot center lies at a transverse momentum of 50 MeV/c, corresponding to a transverse kinetic energy of 1.3 MeV. This recoil kinetic energy is influenced by both the emission source recoil and Coulomb repulsion of the fragments

Figure 1. (color online) Distribution of fragments with Z = 3 in the plane of transverse momentum p

$ _{t} $ versus longitudinal momentum p$ _{z} $ for 124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. Blue lines denote the emission angles in the laboratory frame. 10.2° and 4.5° are the maximum acceptance values of the ALADIN forward spectrometer in the horizontal and vertical directions, respectively.The blue line in the figure represents the emission angle of the fragments in the laboratory system. The acceptance range of the ALADIN spectrometer covers areas with horizontal angle less than 10.2° and vertical angle less than 4.5 °. In Ref. [21], the horizontal and vertical axes are designated as

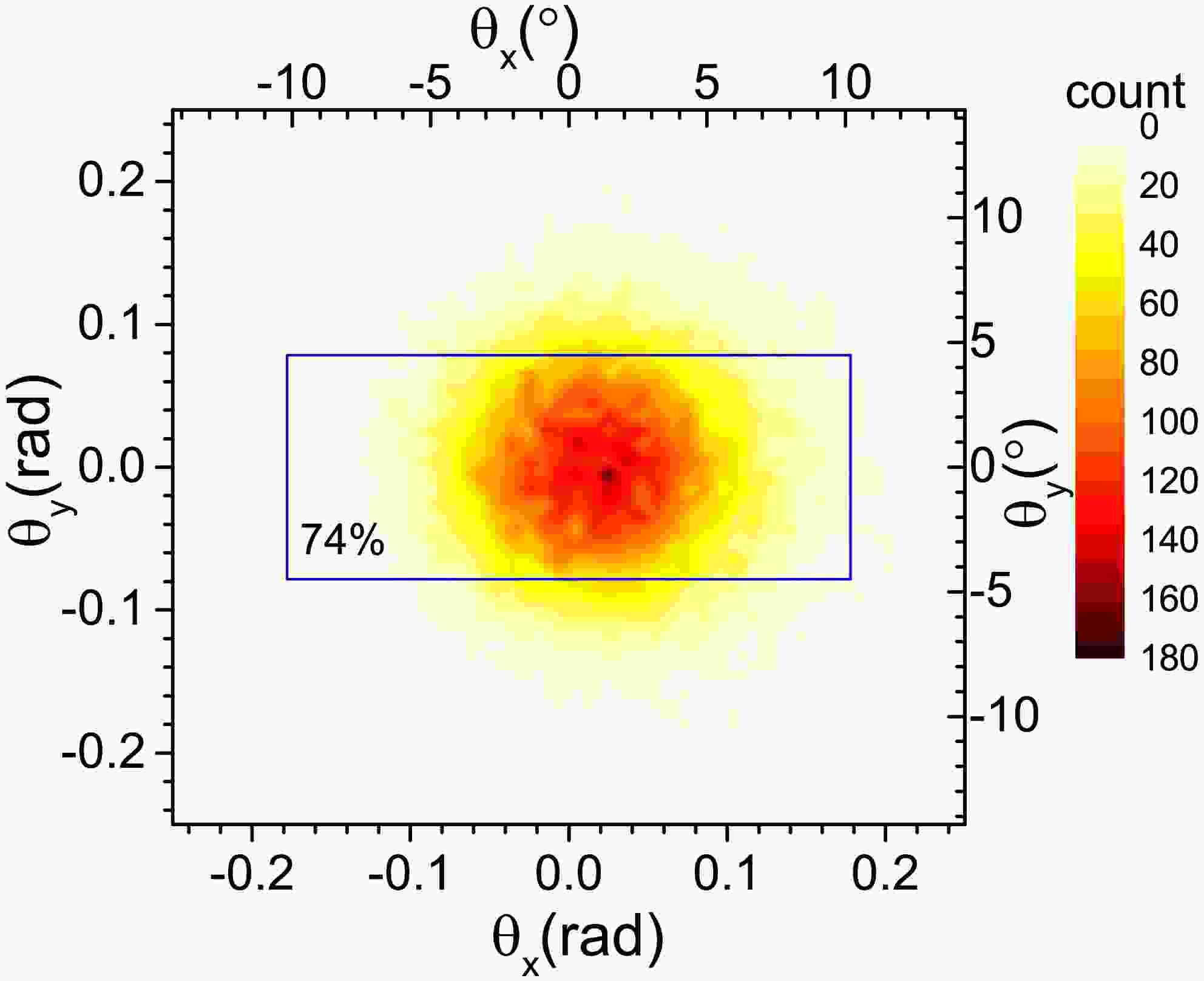

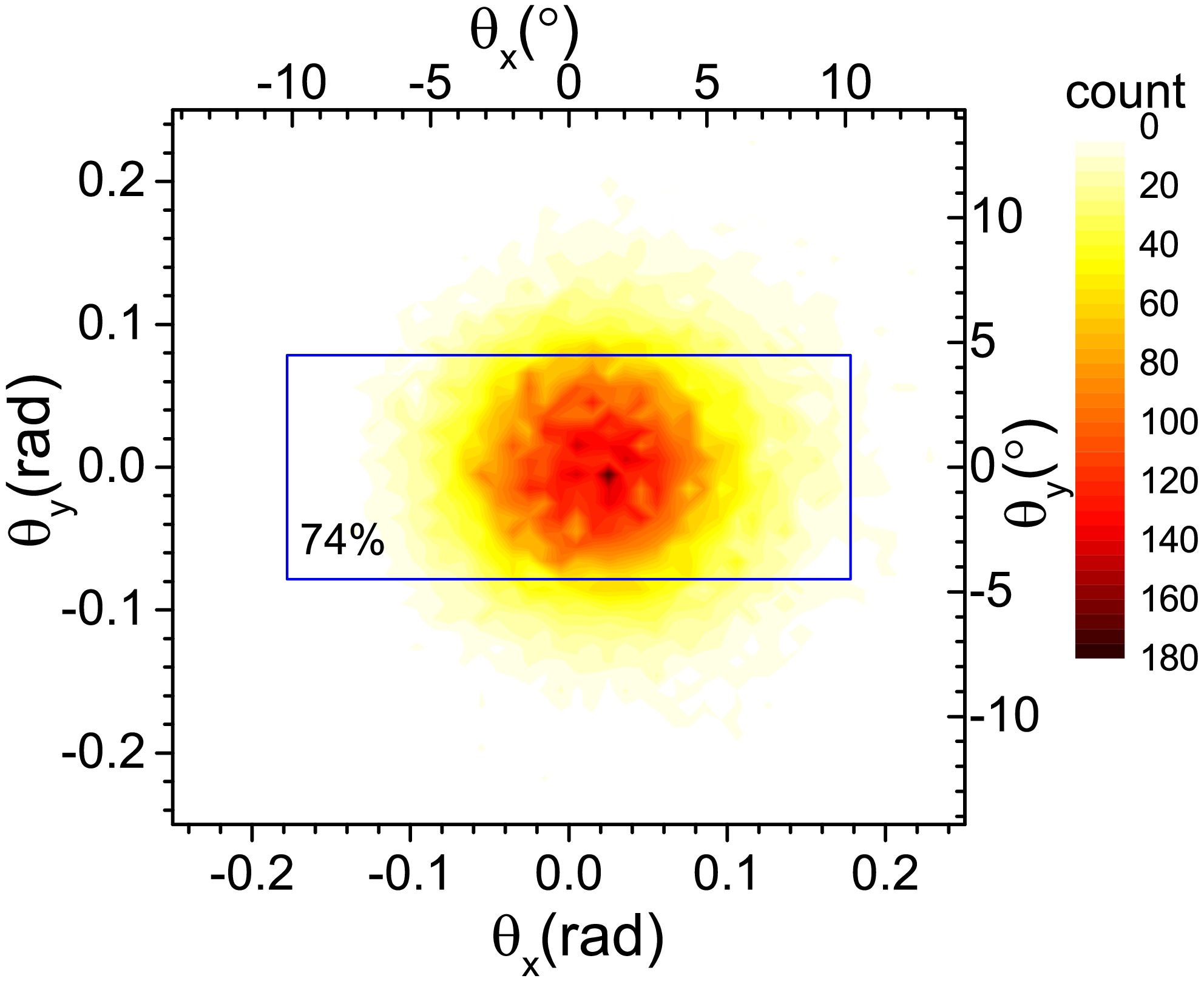

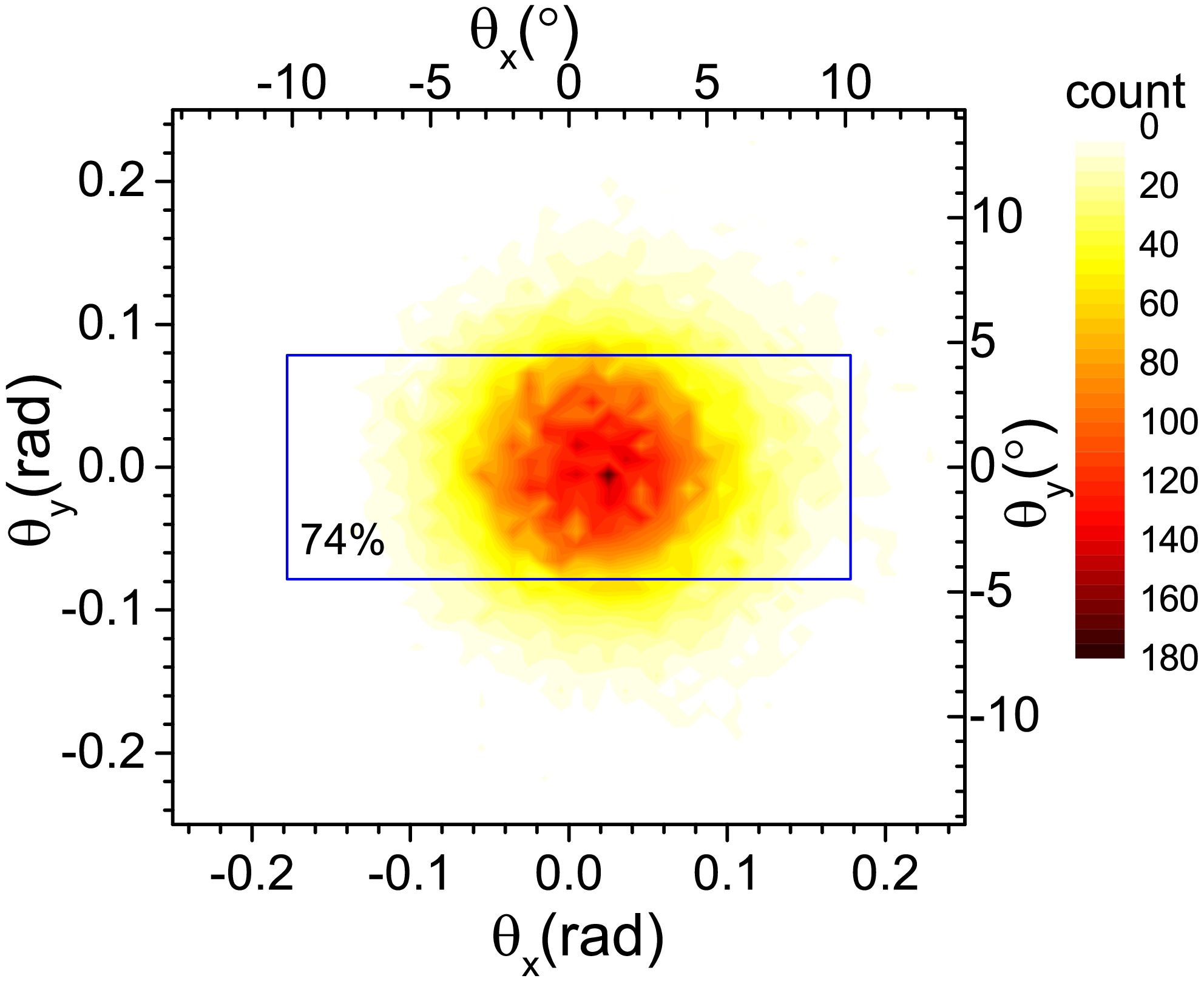

$ y $ and$ x $ , respectively, with the beam direction defined as$ z $ . In the experiment, it is not possible to explicitly identify the collision parameter direction. Instead, the horizontal ($ y $ ) and vertical ($ x $ ) directions are defined by the detector orientation. This axis definition differs from theoretical studies, where the beam incidence direction is typically denoted as$ z' $ , collision parameter direction as$ x' $ , and perpendicular direction as$ y' $ . However, this discrepancy does not affect our analysis owing to the relatively small recoil kinetic energy. Given the small recoil kinetic energy, the fragment emission shows axial symmetry along the$ z $ -axis. Thus, variations in Cartesian coordinate definitions within the plane perpendicular to$ z $ do not impact the dynamic analysis.The ALADIN spectrometer is designed to detect most of the fragments from spectator sources while excluding most of the those from the target-like emission sources. The horizontal acceptance angle of 10.2° is large enough to collect most fragments from the spectator sources, while the vertical acceptance angle of 4.5° is not enough. Some fragments with Z = 3 that have emission angles greater than 4.5° are not detected. This issue is more clearly illustrated by the angular distribution shown in Fig. 2. In the figure, the blue box represents the acceptance region of the ALADIN spectrometer, which extends

$ \pm $ 10.2° horizontally and$ \pm $ 4.5° vertically.

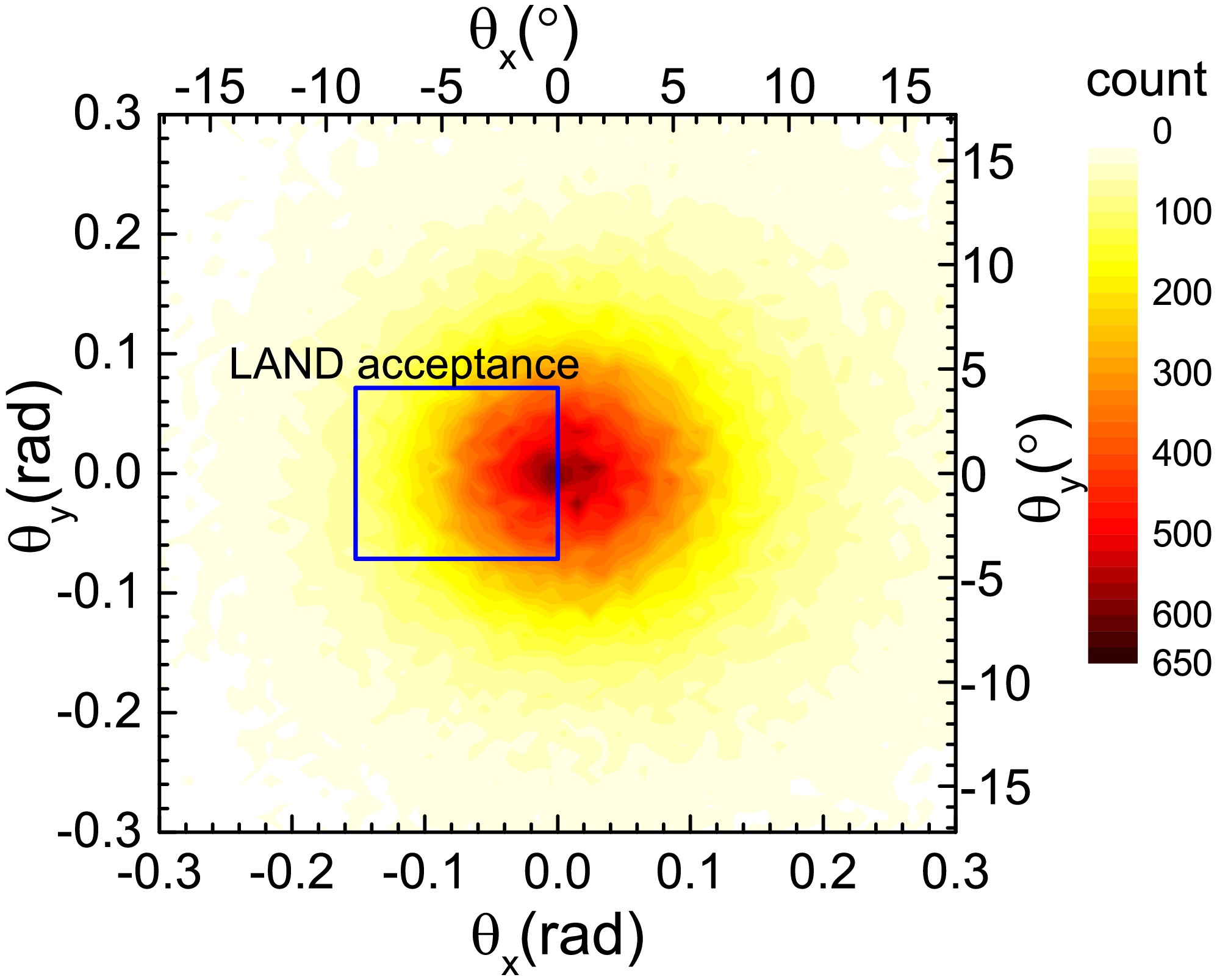

Figure 2. (color online) Probability distribution with respect to the beam direction of the fragment with Z = 3 produced in 124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. The blue square represents the acceptance-area of the ALADIN detector.

In Ref. [19], it is reported that the ALADIN spectrometer captures 90% of Z = 3 fragments. However, our calculations indicate an efficiency of only 74%. This discrepancy is largely due to the recoil effect from the emission source, which impacts the vertical acceptance angle, though the horizontal acceptance angle is sufficiently large. Some fragments escape detection along the horizontal axis. The deviation between experimental and calculated reception efficiencies also stems from an overestimation of the emitter temperature in the IQMD+GEMINI model used for simulations. It should be noted that the reception efficiency increases with the mass number of the emission source, eventually approaching 100% for heavier sources. Therefore, this deviation has a minimal effect on the subsequent discussion of the value of the bounding charge

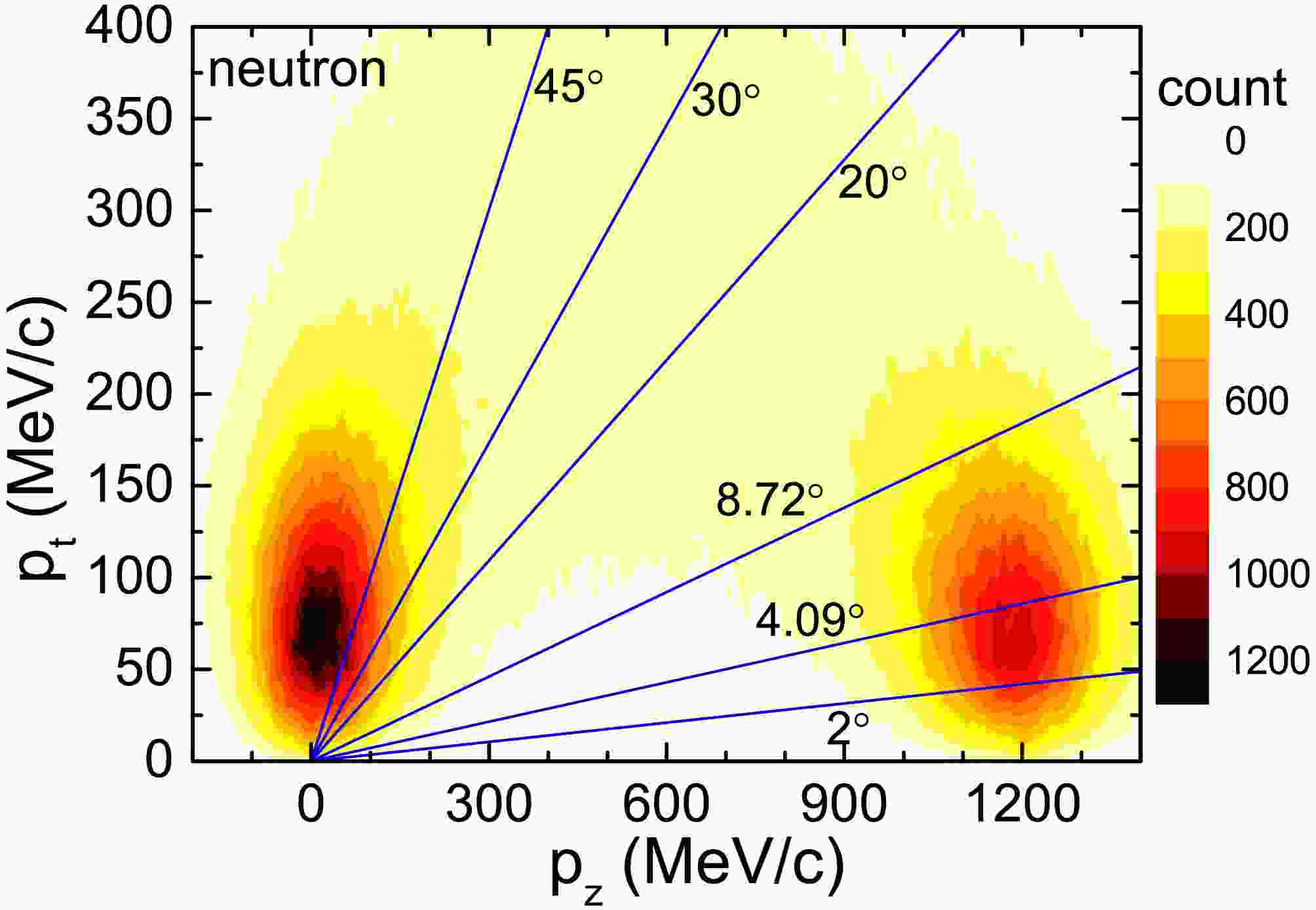

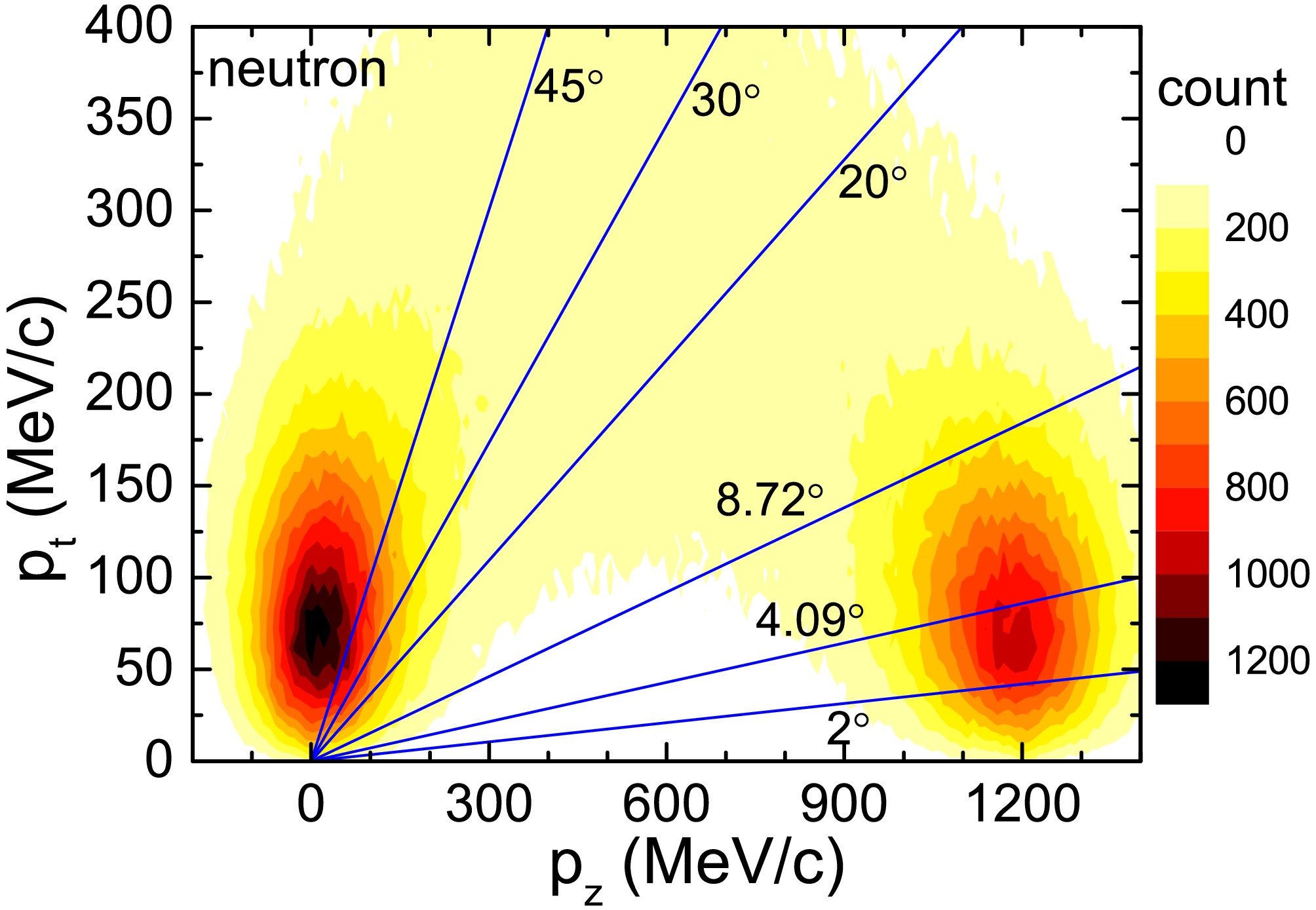

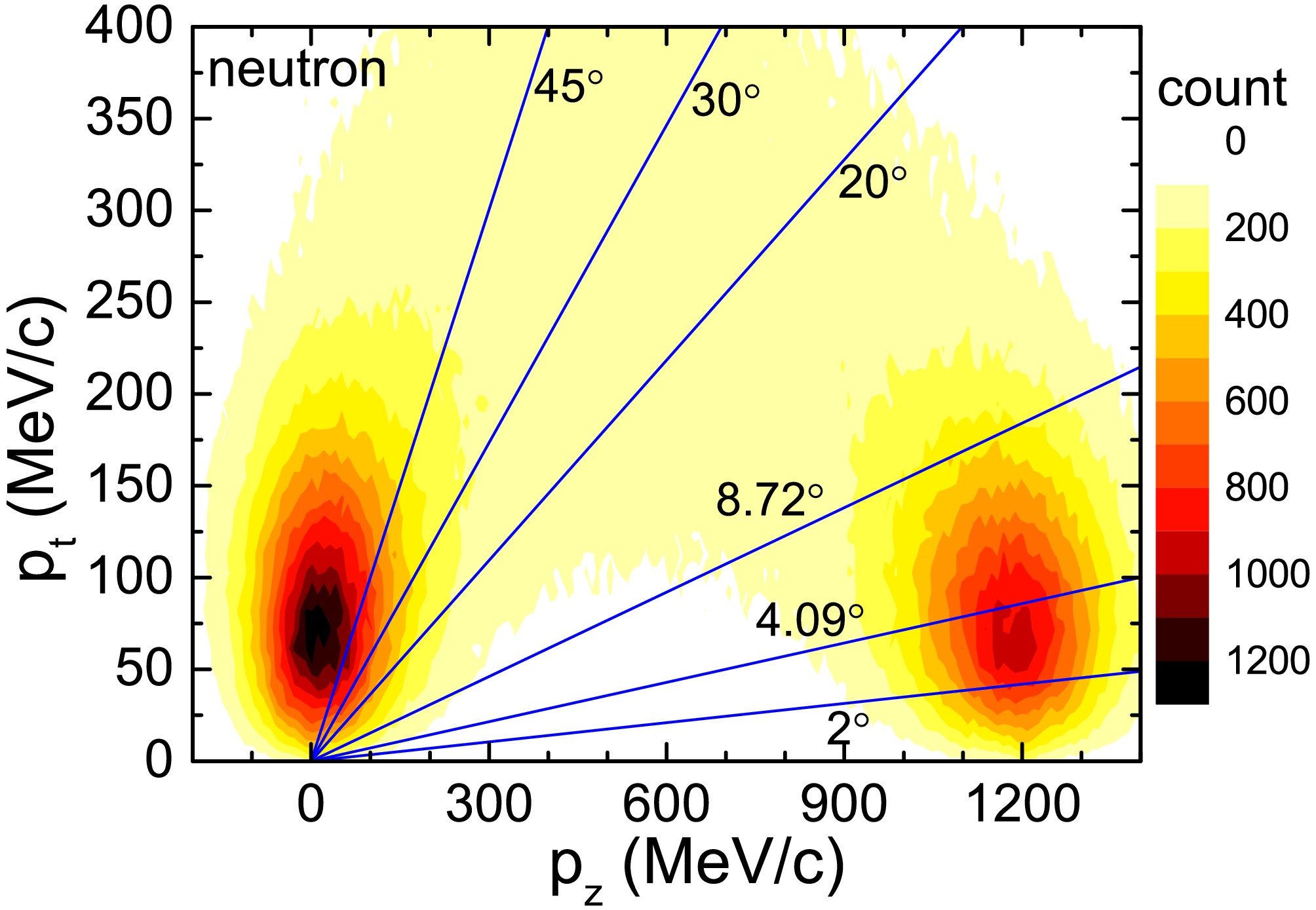

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ .Figure 3 shows the distribution of neutrons in the plane of transverse momentum p

$ _{t} $ versus longitudinal momentum p$ _{z} $ . Neutrons near$ p_z $ = 0 originate from the target-like system, while those near$ p_z $ = 1200 MeV/c come from the projectile-like system. A significant number of neutrons are also distributed over a broad range around$ p_z $ = 600 MeV/c, which are emitted from the participants that acquire substantial transverse momentum due to the intense collision dynamics.

Figure 3. (color online) Distribution of neutrons in the plane of transverse momentum p

$ _{t} $ versus longitudinal momentum p$ _{z} $ for 124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. The blue lines denote emitting angles in the laboratory frame. 8.72° and 4.09° are the maximum acceptance values of LAND in the horizontal and vertical directions, respectively.Neutrons can be emitted throughout the entire heavy-ion collision process, from the pre-equilibrium stage (characterized by violent two-body collisions), through the high-temperature stage of multi-fragmentation, and finally into the lower-temperature stage of secondary decay. By contrast, the Z = 3 fragments (shown in Fig. 1) primarily originate from the multi-fragmentation stage. As a result, the kinetic energy distribution of neutrons is wider than that of the Z = 3 fragments.

The blue line in the figure represents the neutron emission angle. Reference [21] shows that the maximum horizontal acceptance angle of LAND is 8.72°, and the maximum vertical acceptance angle is 4.09°. It is clear that LAND can effectively exclude most neutrons from both the target-like and participant systems.

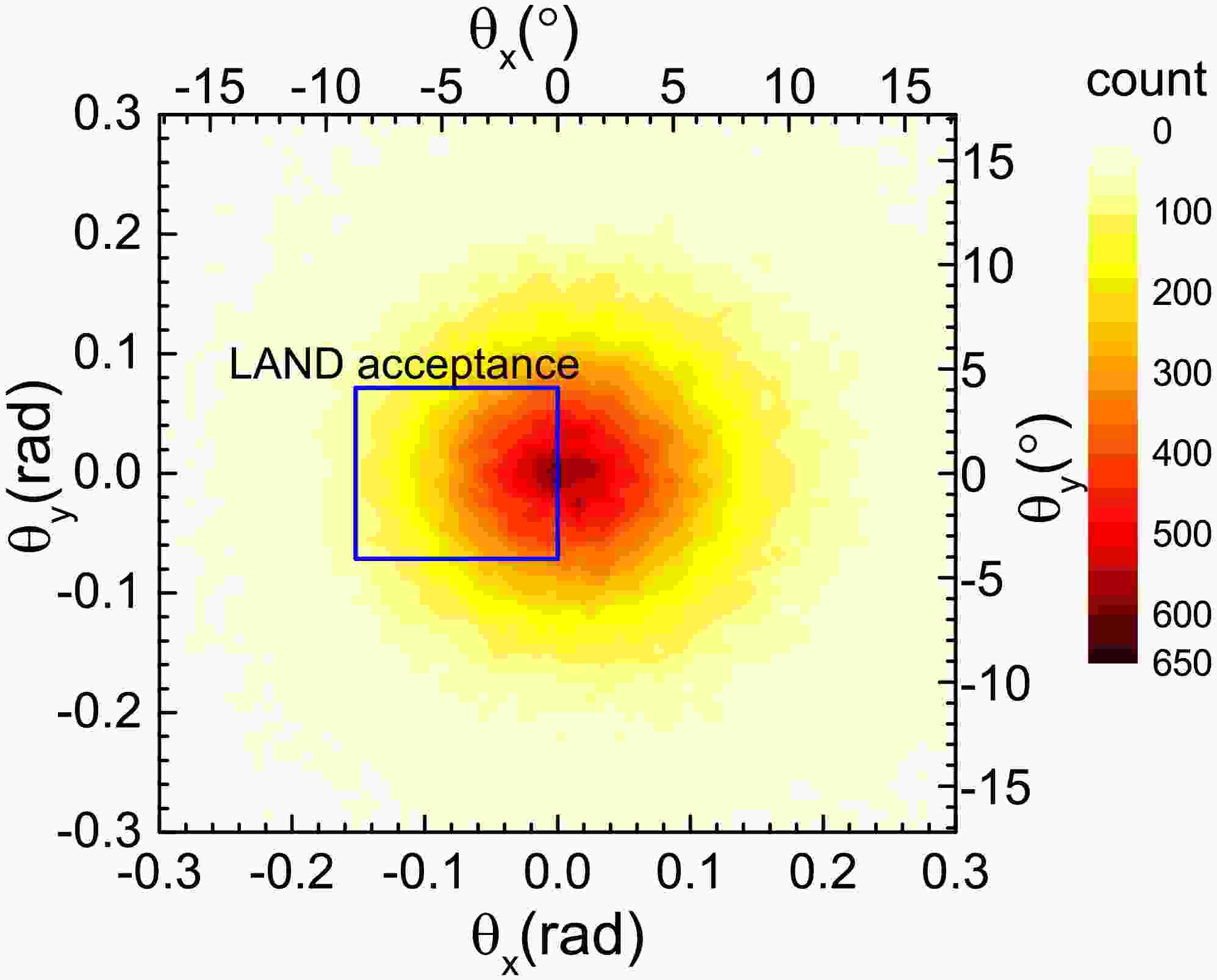

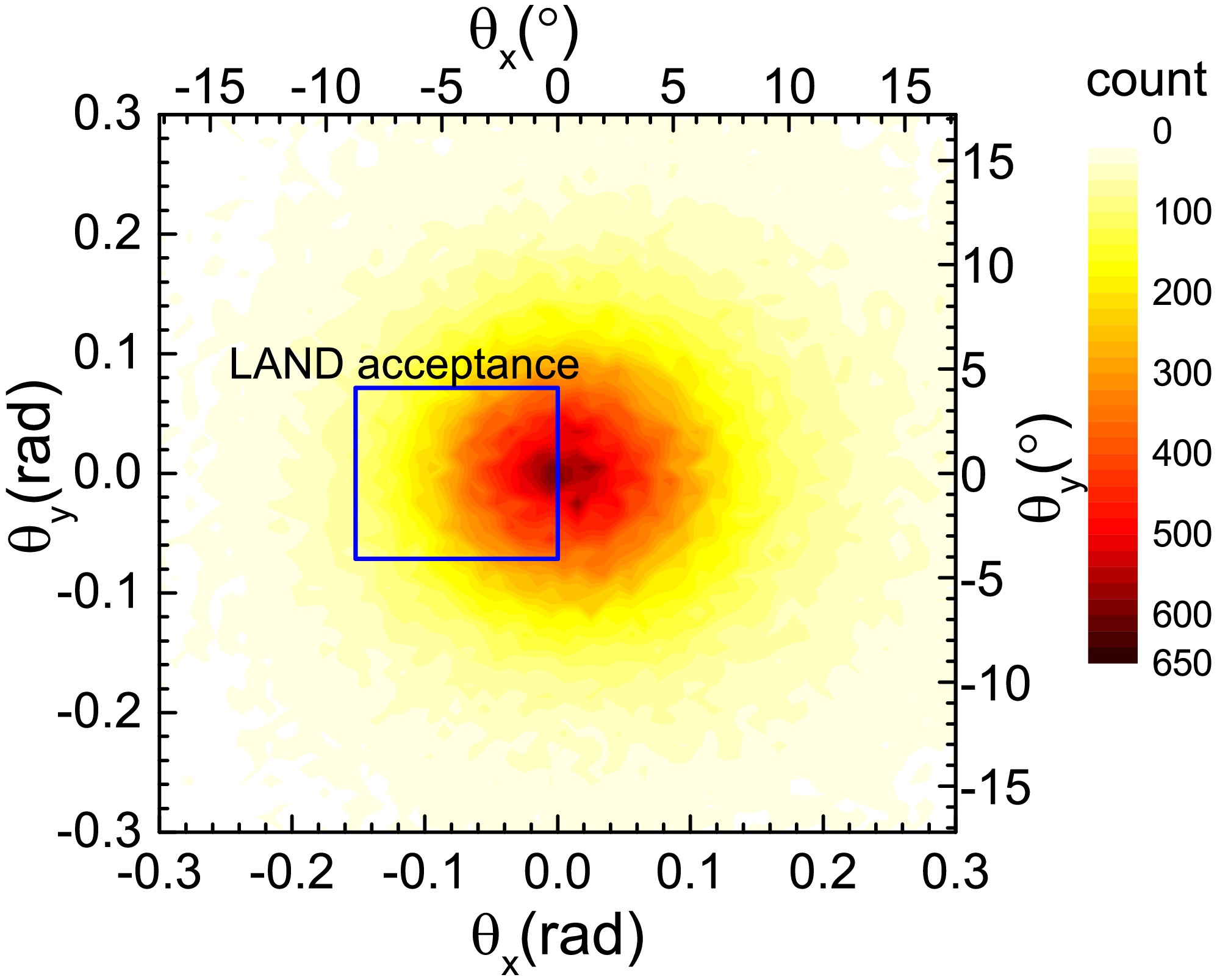

Figure 4 shows the angular distribution of neutrons in the detector's receiving plane. The blue box represents LAND's acceptance region. The center of the neutron distribution is at the origin, and the distribution is circular. LAND covers the angular range 0

$ < $ $ \theta_x $ $ < $ 8.72$ ^\circ $ and$ -4.09^\circ $ $ < $ $ \theta_y $ $ < $ 4.09$ ^\circ $ . The detector does not cover the region where$ \theta_x > 0^\circ $ . However, owing to the symmetry of the system, this limitation does not adversely affect the results. In Ref. [21], a neutron emission source with a temperature of 4 MeV was studied, and it was found that LAND's acceptance for neutrons is 42.4%. However, the model calculations show that LAND's acceptance is lower than this value for neutrons emitted by the bystander emission sources in the reaction. The lower reception efficiency by the IQMD+GEMINI model is caused by the overestimation of the temperature.

Figure 4. (color online) Probability distribution with respect to the beam direction of neutron produced in 124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. The blue square represents the acceptance-area of the LAND.

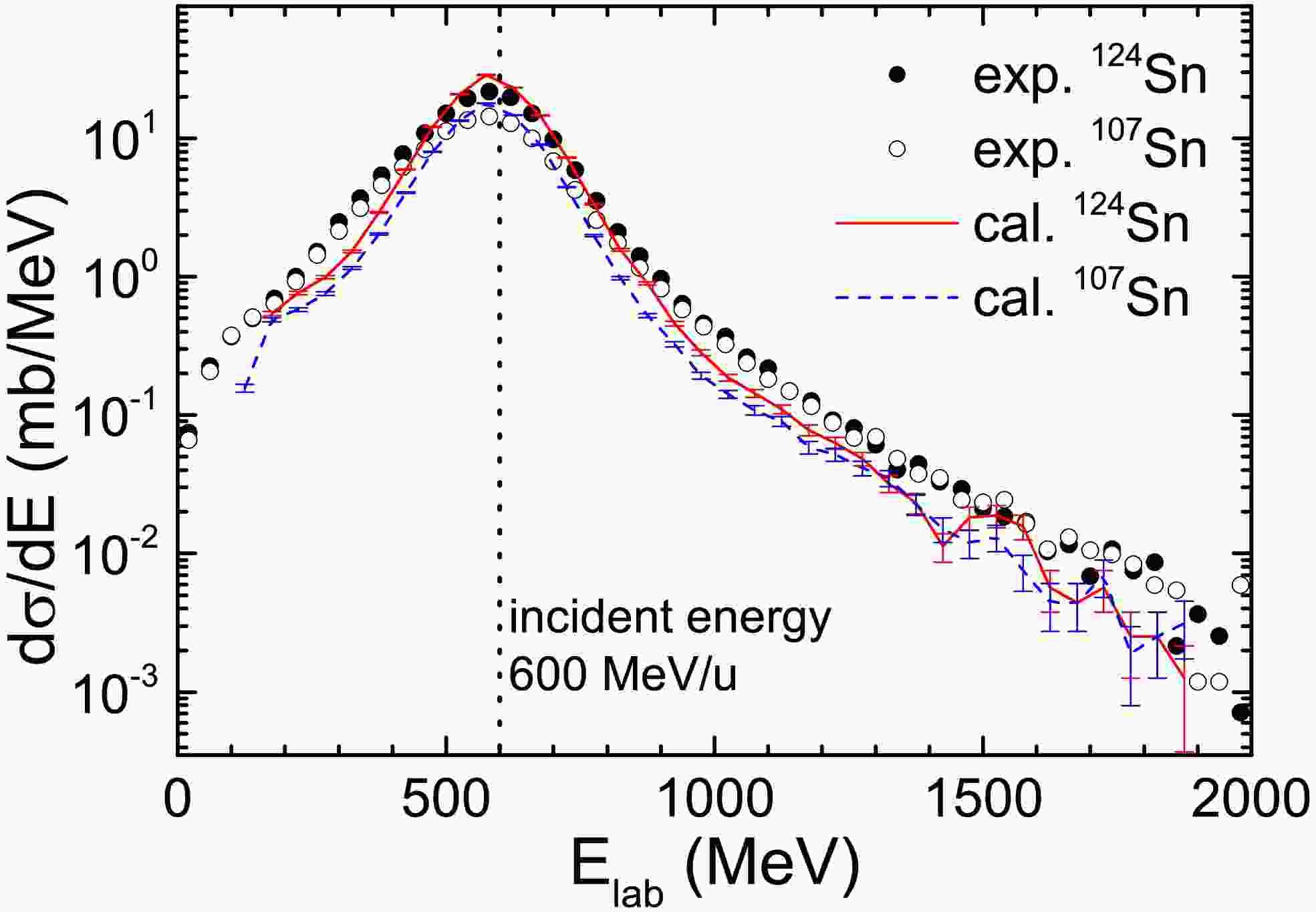

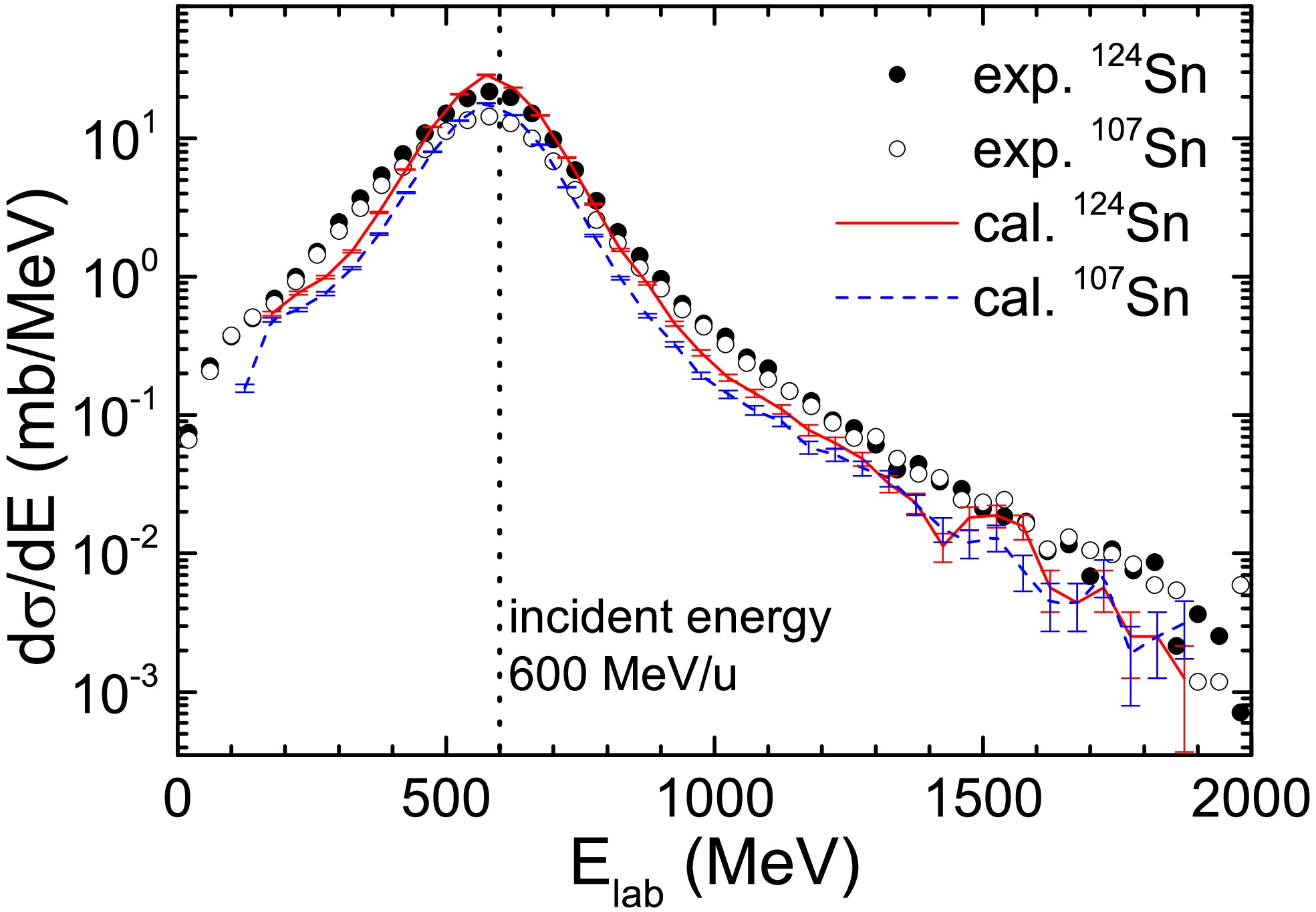

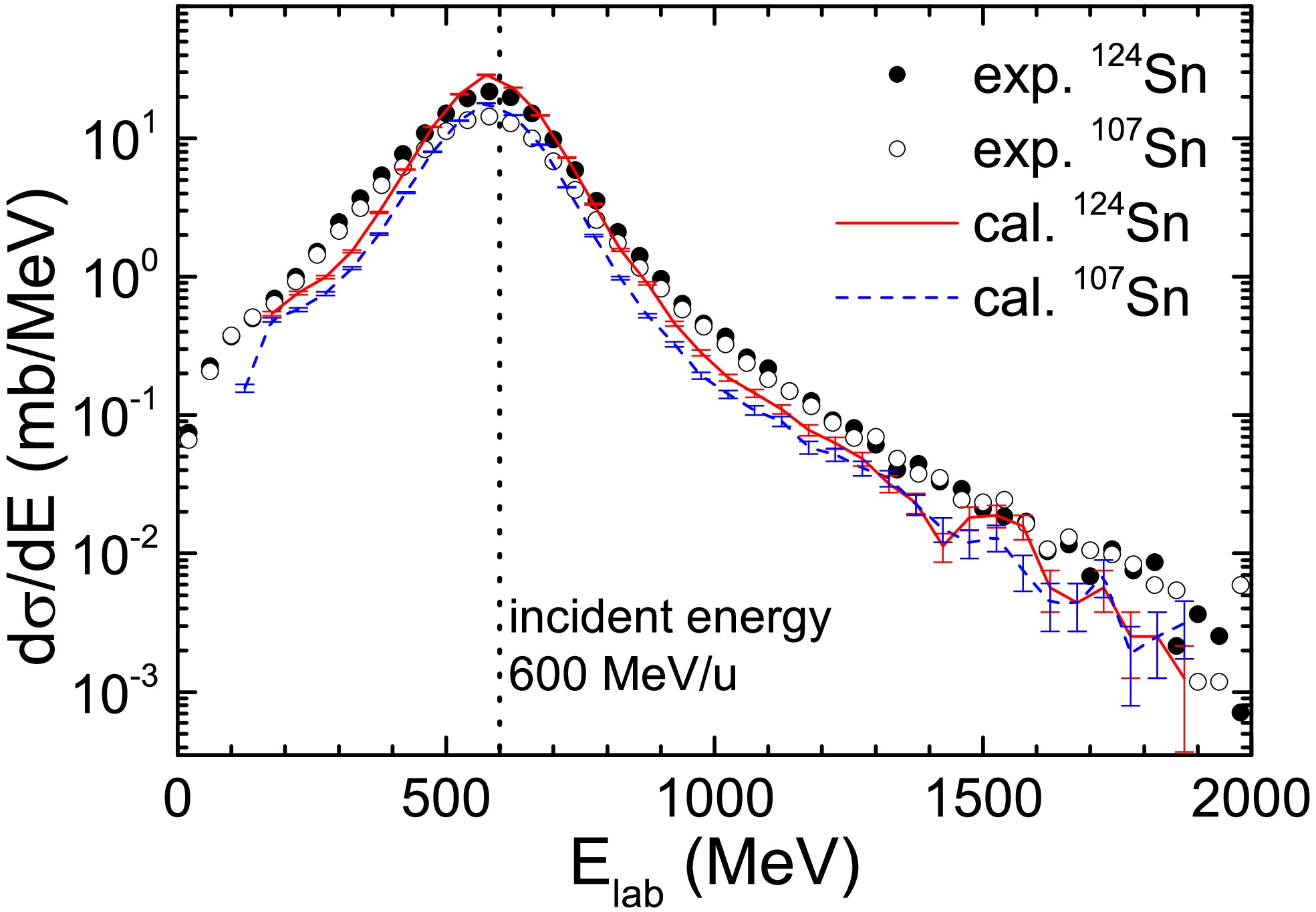

The energy spectrum of neutrons with emission angles less than 2° has been measured in Ref. [21]. The calculated energy spectrum by the IQMD+GEMINI model is compared with the experimental data in Fig. 5. The dashed line in the figure represents an incident energy of 600 MeV/u. Both the experimental and calculated spectra show a peak of the differential cross section at 600 MeV/u, indicating that neutrons emitted at angles less than 2° primarily originate from projectile-like emission sources, with a minimal recoil effect.

Figure 5. (color online) Inclusive differential cross section of neutrons in the laboratory detected within the solid angle

$ \theta_{\rm lab} $ $ < $ 2° for the 107,124Sn + 120Sn collisions at 600 MeV/nucleon. The experimental data are taken from Ref. [21].The experimental energy spectra for the

$ ^{124} \text{Sn} $ and$ ^{107} \text{Sn} $ systems have similar shapes, but the cross section for the$ ^{124} \text{Sn} $ system is slightly larger than that for$ ^{107} \text{Sn} $ . For the$ ^{124} \text{Sn} $ system, the peak value is 21.7 mb/MeV, while for the$ ^{107} \text{Sn} $ system, the peak value is 4.3 mb/MeV. The calculations capture the overall shape and system dependence of the experimental energy spectrum: the peak occurs at 600 MeV, and the peak for the$ ^{124} \text{Sn} $ system is larger than that for the$ ^{107} \text{Sn} $ system. However, the energy spectrum predicted by the model is somewhat narrower than the experimental spectrum.The GEANT4 toolkit was used in Ref. [21] to simulate a

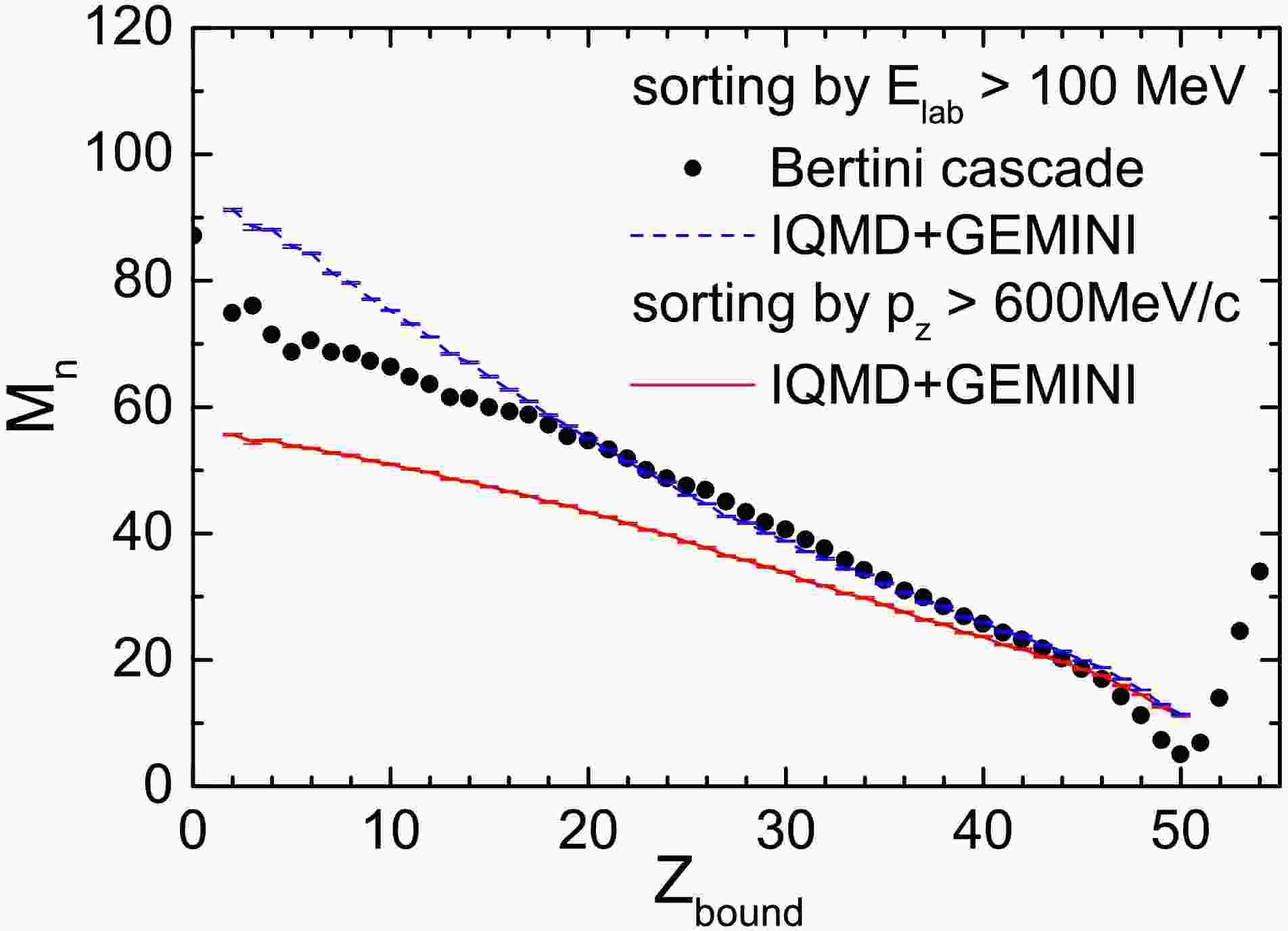

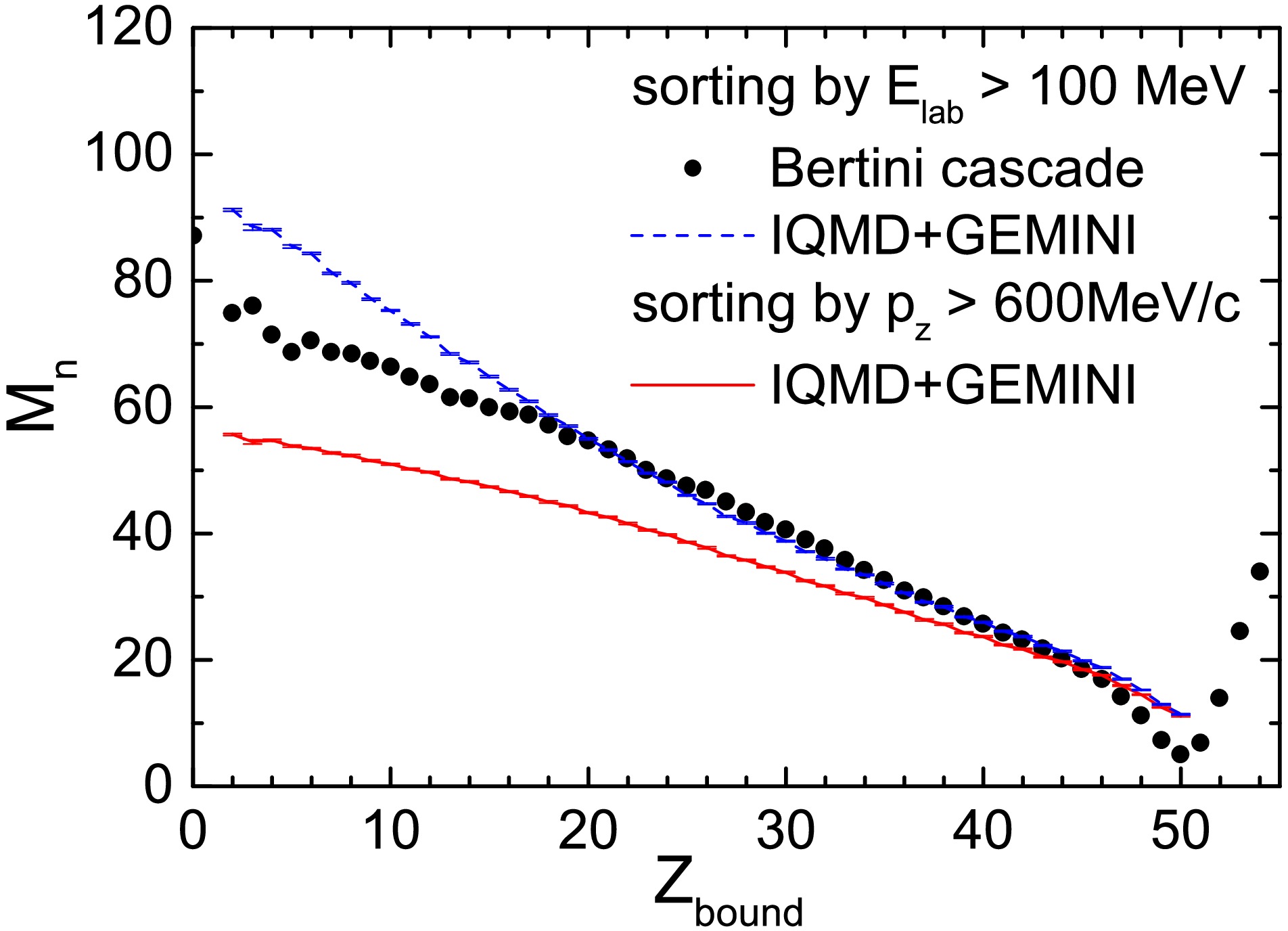

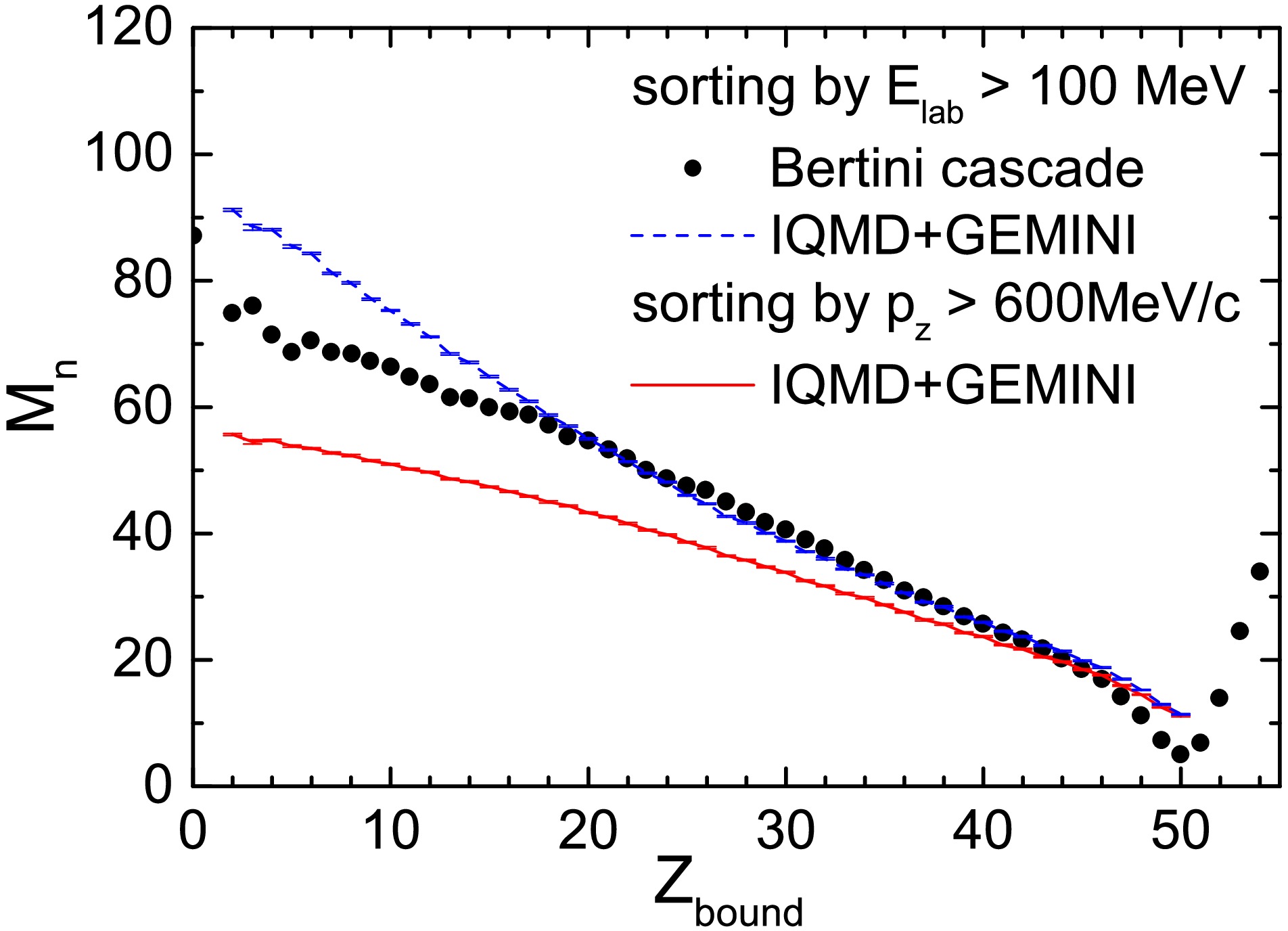

$ ^{124}\text{Sn} $ beam at 600 MeV/u incident on a 0.5 mm thick Sn target, calculating neutron multiplicity as a function of$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ , as shown by the dots in Fig. 6. The GEANT4 simulations employ the Bertini cascade model. In the calculations, neutrons emitted from secondary de-excitations of target fragments are excluded by applying the condition$ E_{\text{lab}} $ $ > $ 100 MeV. Following this criterion, we obtain the neutron multiplicity as a function of$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ from the IQMD+GEMINI model, represented by the blue curve in Fig. 6.

Figure 6. (color online) Neutron multiplicity as a function of

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ for 124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. The circles represent the calculations by the Bertini cascade implemented in GEANT4 taken from Ref. [21].In the range 20

$ < $ $ Z_{\text{bound}} $ $ < $ 45, the IQMD+GEMINI model and the Bertini cascade model yield closely matching results. Differences appear, however, in peripheral and central collision regions. For peripheral collisions, the neutron multiplicity predicted by the Bertini cascade model is lower than that predicted by the IQMD+GEMINI model. At$ Z_{\text{bound}} = 50 $ , the cascade model gives a neutron multiplicity of 4, while the IQMD+GEMINI model predicts 11. This discrepancy reflects differences in the predicted isotopic distribution of Sn fragments: the IQMD+GEMINI model suggests more neutron-deficient isotopes. If only quasi-projectile fragments are considered, the maximum$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ should be 50. However, the cascade model shows results even for$ Z_{\text{bound}} > 50 $ , possibly due to the method for selecting quasi-projectile fragments.In central collisions, neutron multiplicity steadily increases as

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ decreases. For instance, at$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ = 2, the cascade model predicts a neutron multiplicity near 80, while the IQMD+GEMINI model suggests a higher count, reaching 91 free neutrons. Notably, using$ E_{\text{lab}} $ $ > $ 100 MeV to filter for neutrons from projectile fragmentation is not the optimal method. As shown in Fig. 3, the single-nucleon momentum of the projectile is approximately 1200 MeV/c in the experimental frame. Applying a transverse momentum filter of$ p_z $ $ > $ 600 MeV/c more effectively selects neutrons originating from projectile fragmentation.The neutron multiplicity filtered by

$ p_z $ $ > $ 600 MeV/c is depicted by the red curve in Fig. 6. This criterion selects fewer neutrons than the$ E_{\text{lab}} $ $ > $ 100 MeV threshold. At$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ = 2, neutron multiplicity reaches 59, indicating that for central collisions, 59 of the 70 neutrons in the$ ^{124}\text{Sn} $ projectile are released as free neutrons, while the remaining 11 are emitted as deuterons or tritons.In fact, the neutrons selected using the condition

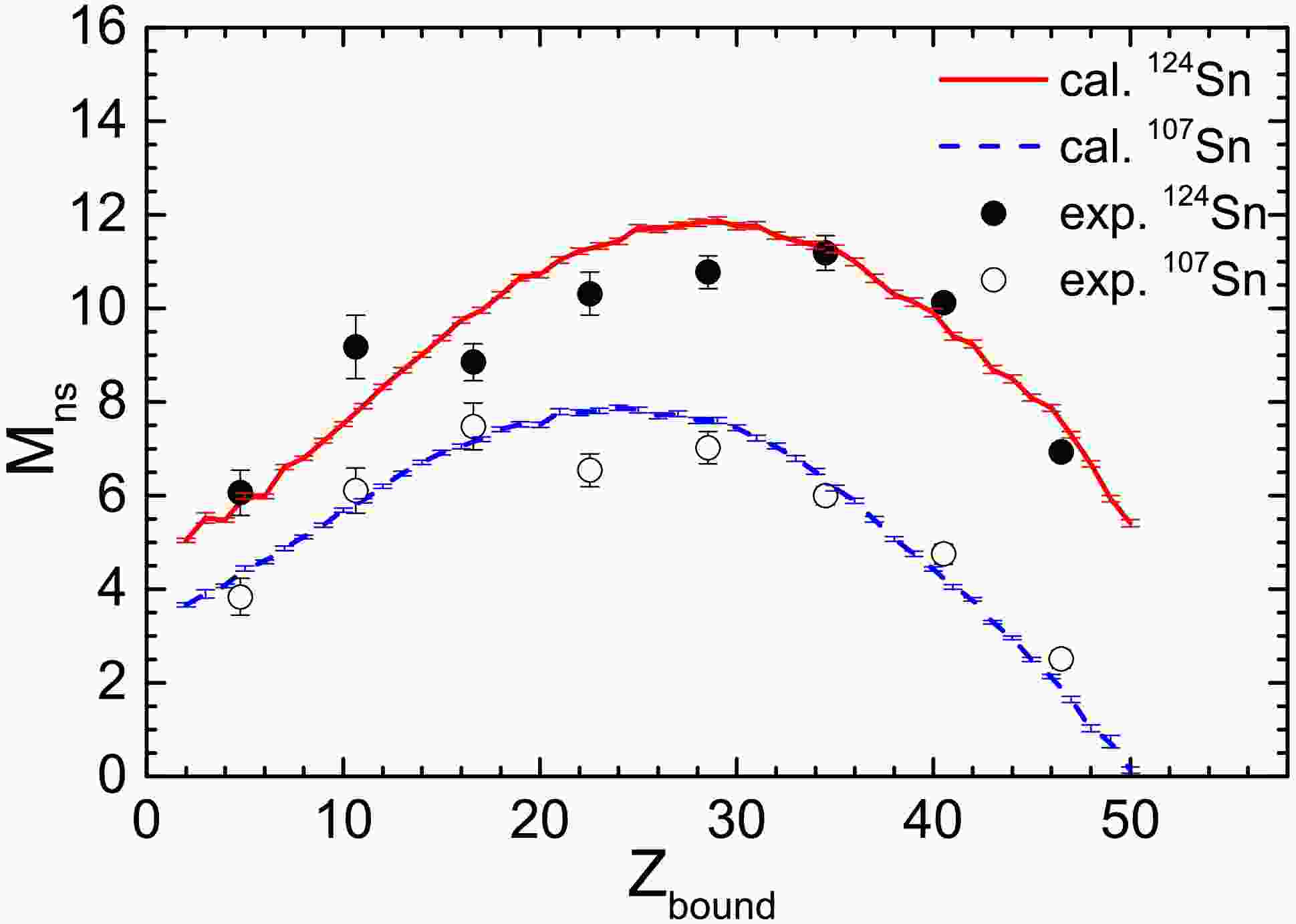

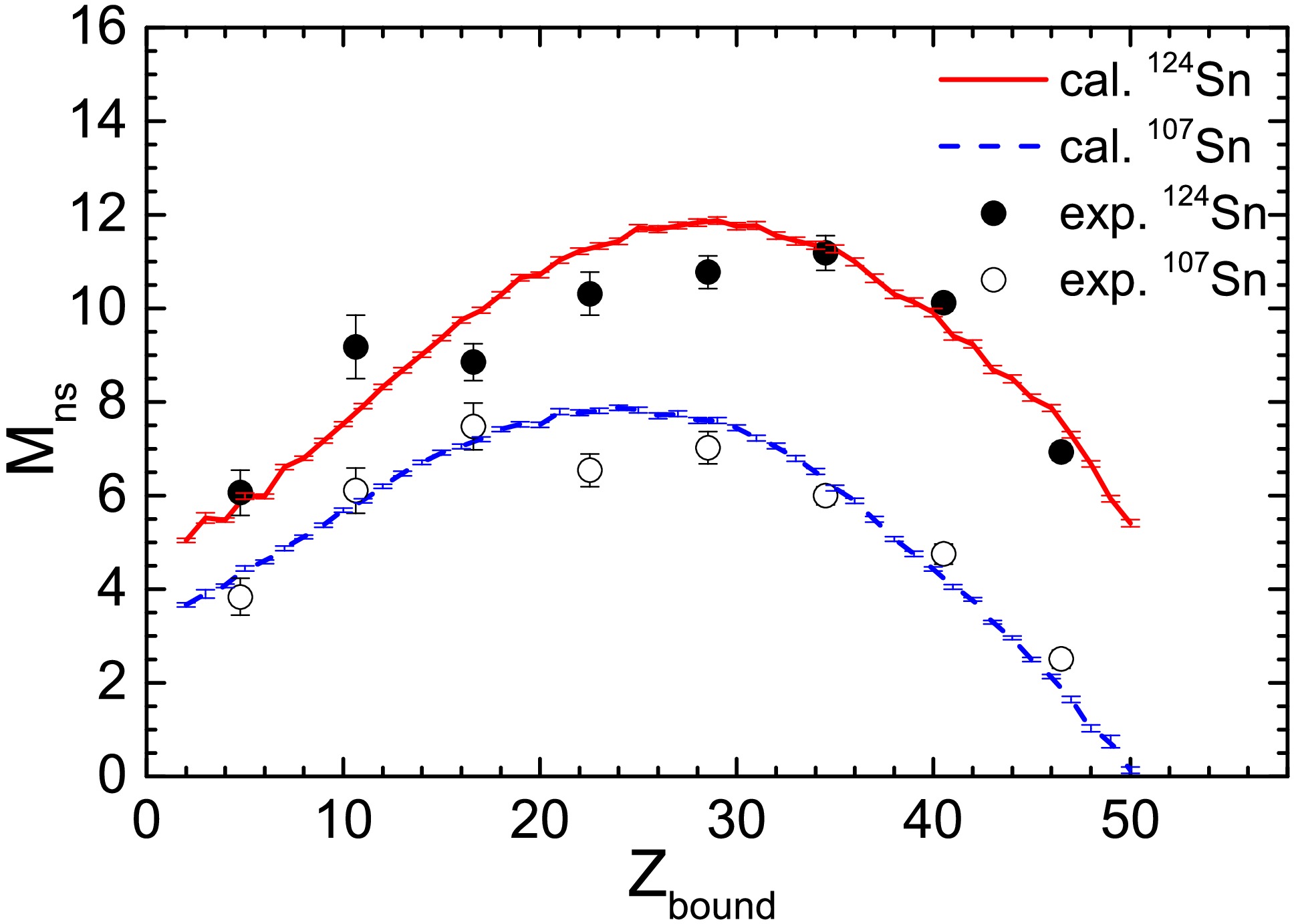

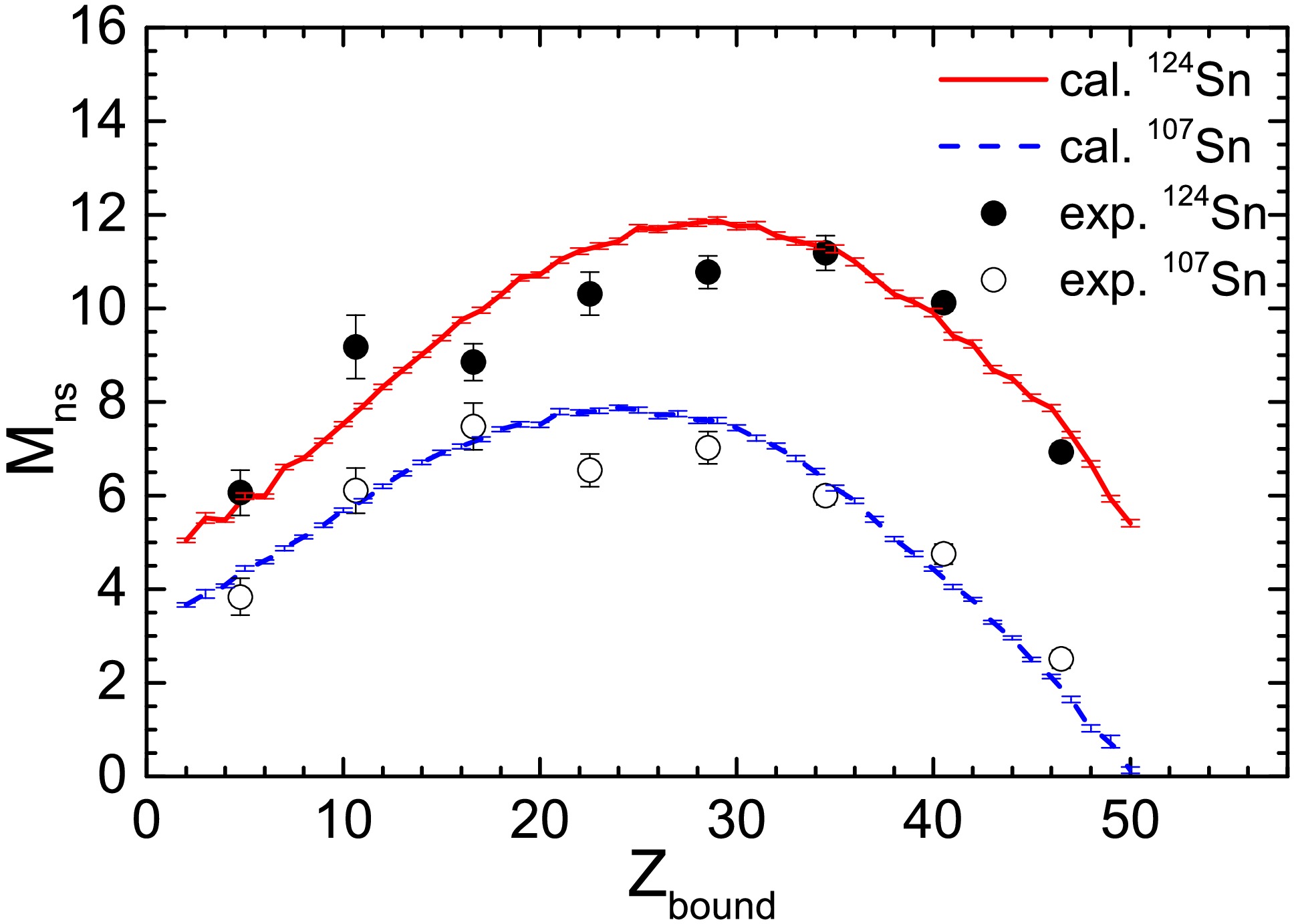

$ p_z $ $ > $ 600 MeV/c do not originate from a single equilibrated thermal source. During the early stages of projectile-target collisions, neutrons are emitted from one side of the projectile due to intense collisions. These neutrons are associated with the participant zone and exhibit a higher temperature. After the violent collision process ends, part of the projectile is sheared off, leaving an excited remnant (i.e., the spectator source), which de-excites through nucleon emission and multi-fragmentation. By isolating this subset of neutrons, the momentum distribution of the neutrons can provide insights into the spectator source characteristics. In Ref. [21], the condition 1000 MeV/c$ < $ $ p_z $ $ < $ 1500 MeV/c is used to select neutrons originating from the spectator source. We used the same method to extract neutrons originating from the spectator source. Figure 7 shows the experimental and theoretical neutron multiplicity as a function of$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ . Experimental data indicate that as$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ increases, the neutron multiplicity first rises and then falls. This trend is similar to the variation in intermediate-mass fragment (IMF) multiplicity with$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ . For events around$ Z_{\text{bound}} \approx 30 $ , the spectator source primarily undergoes multi-fragmentation during de-excitation, leading to the emission of a larger number of neutrons. By contrast, for events with smaller or larger$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ , the spectator source is either smaller or has lower excitation energy, resulting in fewer emitted neutrons.

Figure 7. (color online) Neutron multiplicity of the projectile source as a function of

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ for 107,124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. The neutrons from the projectile source are sorted by$ 1000 \, \text{MeV}/c < p_z < 1500 \, \text{MeV}/c $ The experimental data are taken from Ref. [21].Comparing the results for the

$ ^{124}\text{Sn} $ and$ ^{107}\text{Sn} $ projectiles reveals that$ ^{124}\text{Sn} $ leads to a neutron-rich spectator, producing higher neutron multiplicity. Conversely,$ ^{107}\text{Sn} $ results in a neutron-deficient spectator, yielding lower neutron multiplicity. However, the difference in neutron multiplicity between the two systems is approximately 4, which is smaller than the neutron number difference of 17 between$ ^{124}\text{Sn} $ and$ ^{107}\text{Sn} $ . This suggests that during the violent collision stage, before the formation of the equilibrated spectator source, the excess neutrons in$ ^{124}\text{Sn} $ are largely emitted, causing the neutron multiplicities of the spectator sources in both systems to converge.Comparing the IQMD+GEMINI model calculations with experimental data shows a high degree of consistency. Combined with the multiplicity observables reported in the literature, we can conclude that the IQMD+GEMINI model accurately captures the primary features of the collision dynamics in

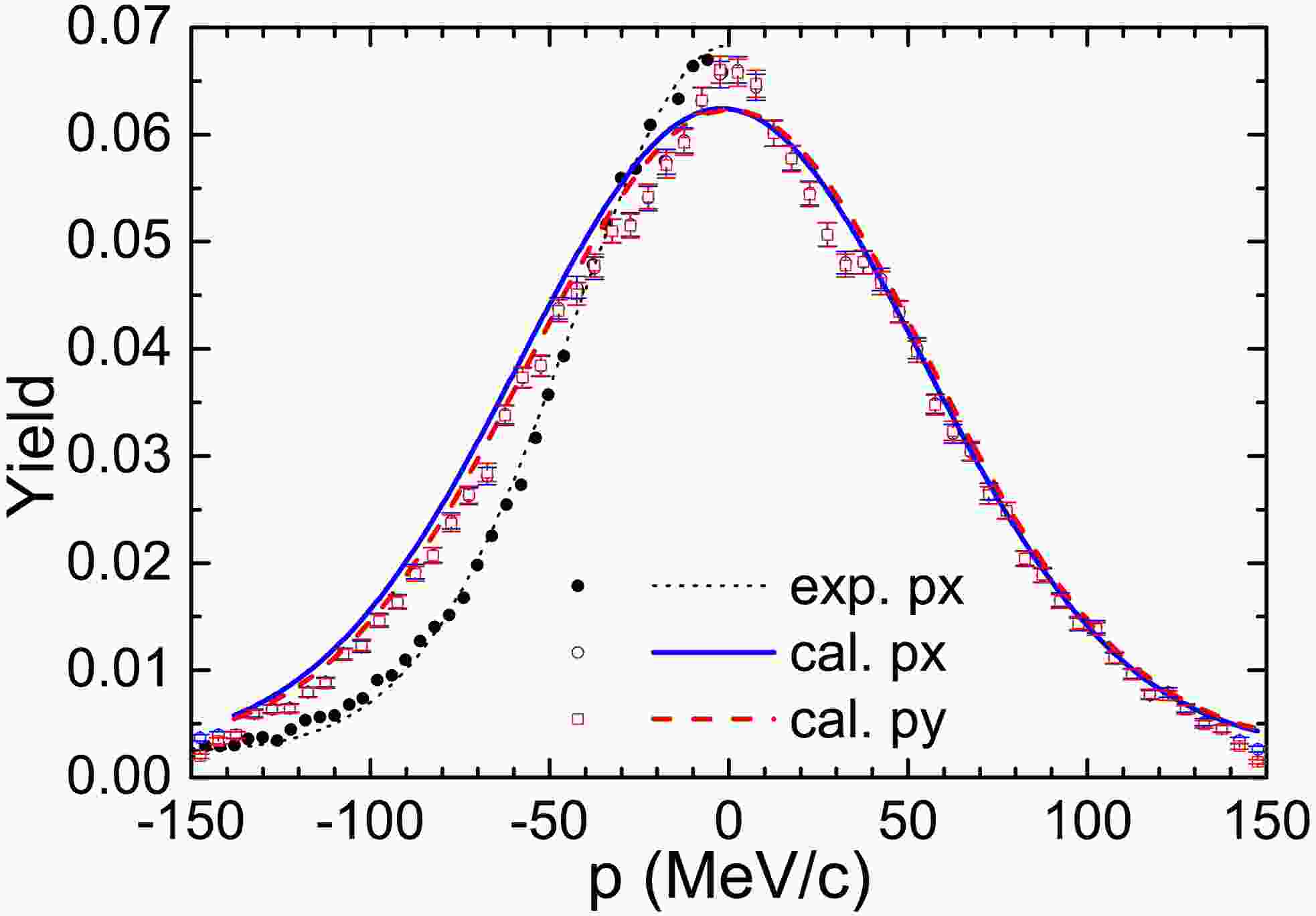

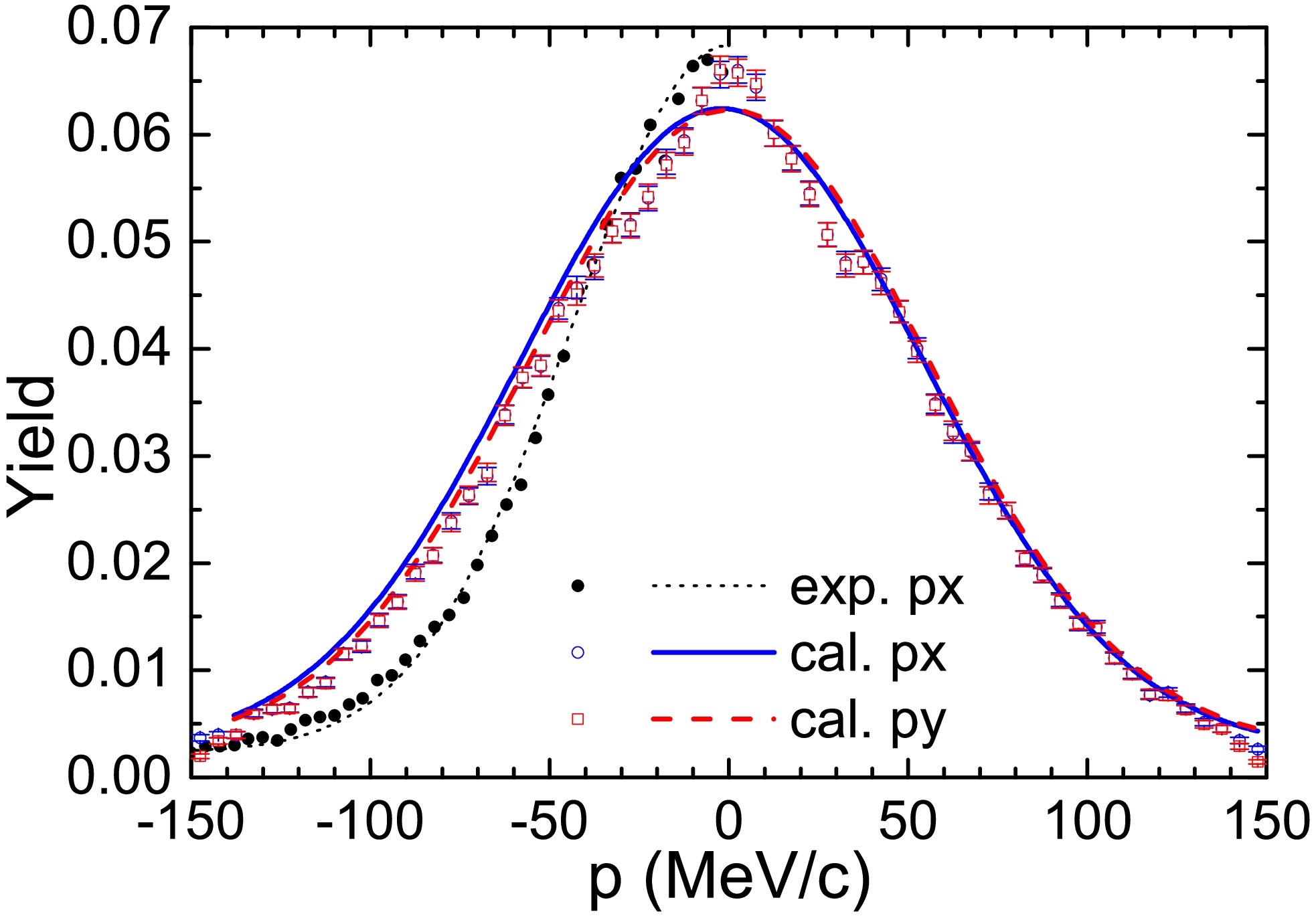

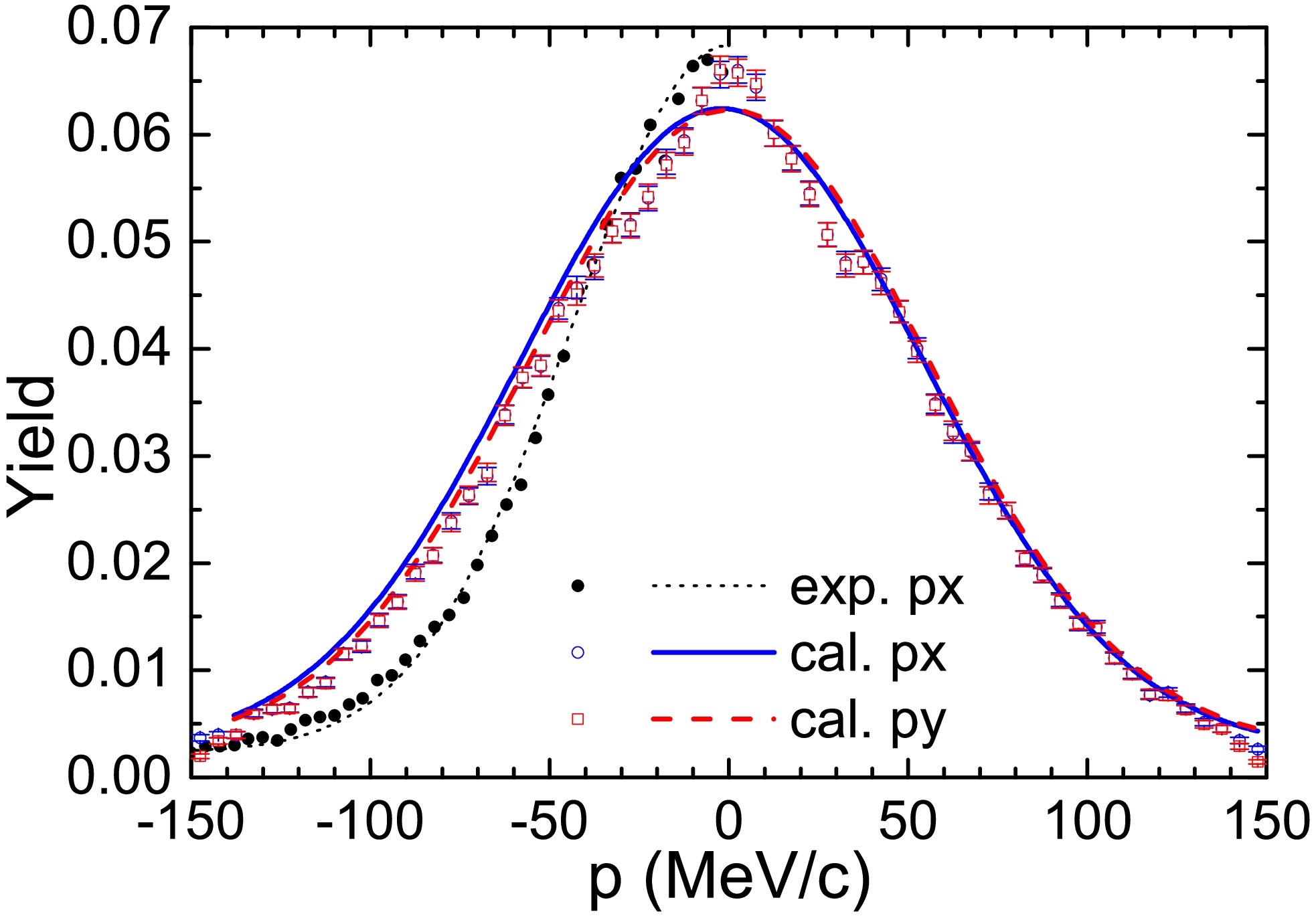

$ ^{124}\text{Sn} + ^{120}\text{Sn} $ reactions. This provides a reliable foundation for the subsequent analysis of the spectator source temperature.We adopted the same method and calculated the transverse momentum distribution of these neutrons, as shown in Fig. 8. The full circles are the experimental data. The (blue) open circles and (red) open squares are the calculated distributions of

$ p_{y} $ and$ p_{x} $ , respectively. The neutron density distribution in the$ p_{y} $ vs$ p_{x} $ plane is assumed to be a classical Maxwellian function added to a constant background pedestal.

Figure 8. (color online) Distribution of transverse momentum for neutrons from the fragmentation of 124Sn projectiles, selected with the condition

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ $ \geqslant $ 45. The full circles and the dotted curve denote the experimental data and corresponding fit. The (blue) open circles and (red) open square are the calculated distributions of$ p_{x} $ and$ p_{y} $ , respectively. The (blue) curve and (red) dash illustrate the corresponding fits. The data are taken from Ref. [21].$ \begin{aligned} \frac{\partial^{2}N}{\partial p_{x}\partial p_{y}} = C_{1} \exp\left(-\frac{p_{x}^{2}+p_{y}^{2}}{2mT^{2}}\right) +C_{2}. \end{aligned} $

(8) where

$ m $ is the neutron mass,$ C_{1} $ and$ C_{2} $ are the fitting parameters, and$ T $ is the temperature parameter. To find the temperature parameter, the distribution of$ p_{x} $ (or$ p_{y} $ ) is fitted. The fit of experimental data with a Gaussian distribution corresponding to$ T $ = 2.04 MeV superimposed on a constant background is represented by the dotted line. The cases for the calculated$ p_{x} $ and$ p_{y} $ distributions are represented by the (blue) curve and (red) dash. The corresponding temperature parameters are$ T_{x} $ = 3.37 MeV and$ T_{y} $ = 3.31 MeV, which are significantly higher than the experimental value.The figure raises a critical question: why does the theoretical transverse momentum distribution exhibit a certain broadening compared to experimental data? In other words, why the temperatures extracted from neutron momentum distributions calculated by the IQMD+GEMINI model are overall higher than the experimental data? In fact, the neutron emission comprises two distinct sources, the participant and spectator sources. The constant

$ C_{2} $ in Eq. (8) describes this two-source effect, where the participant source is assumed to contribute a small amount of and temperature-independent neutrons to the detection region. If the model overestimates contributions of neutrons from the participant source, the fitting formula (Eq. 8) will not be applicable to the theoretical spectra.By replacing constant

$ C_{2} $ with a Maxwellian distribution and considering the recoil effect of the spectator source, we derive the following neutron distribution formula:$ \begin{aligned} \frac{\partial^{2}N}{\partial p_{x}\partial p_{y}} = C_{1} \exp\left[-\frac{(p_{x}-p_{x0})^{2}+p_{y}^{2}}{2mT_{s}^{2}}\right] +C_{2}\exp\left(-\frac{p_{x}^{2}+p_{y}^{2}}{2mT_{p}^{2}}\right). \end{aligned} $

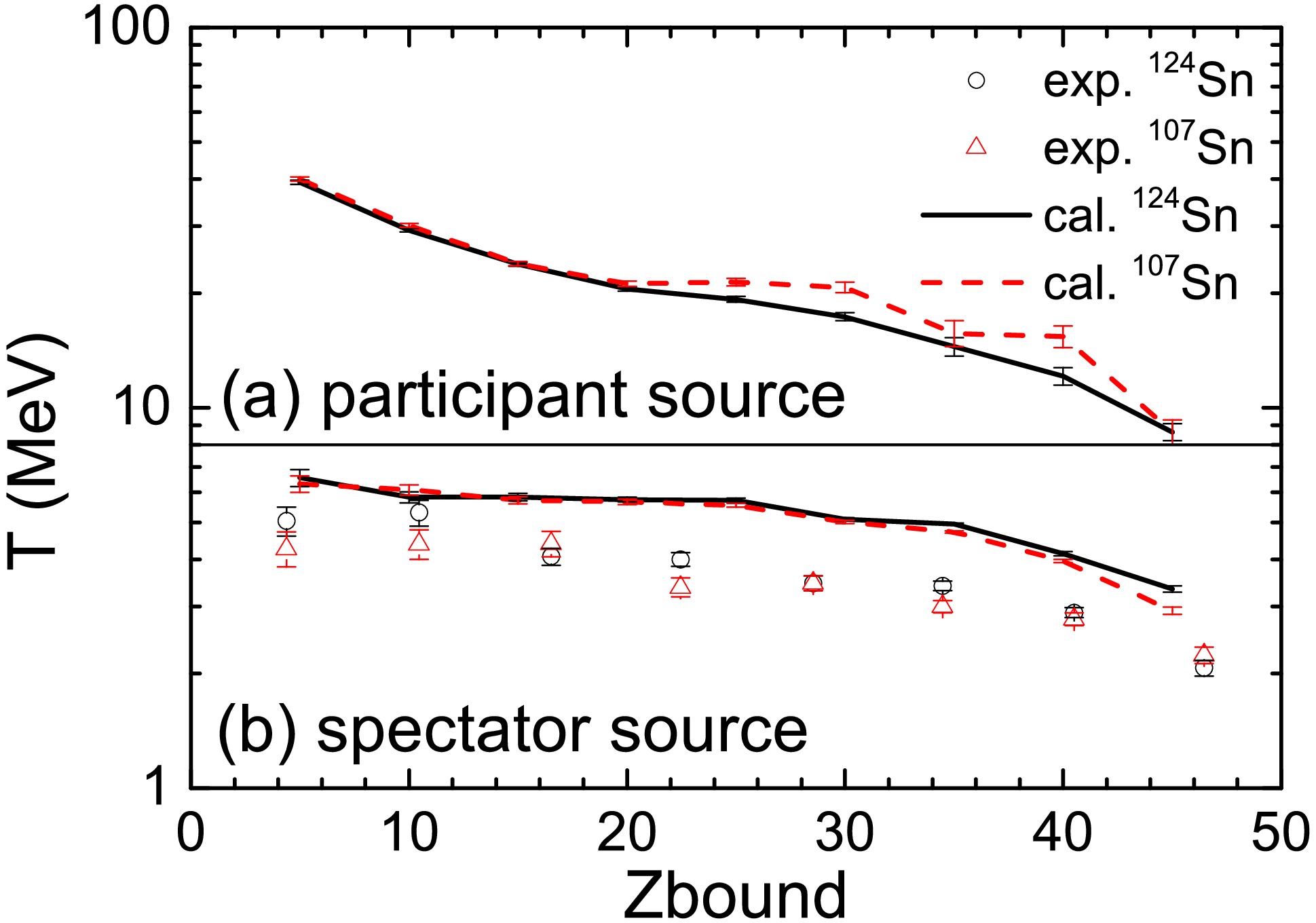

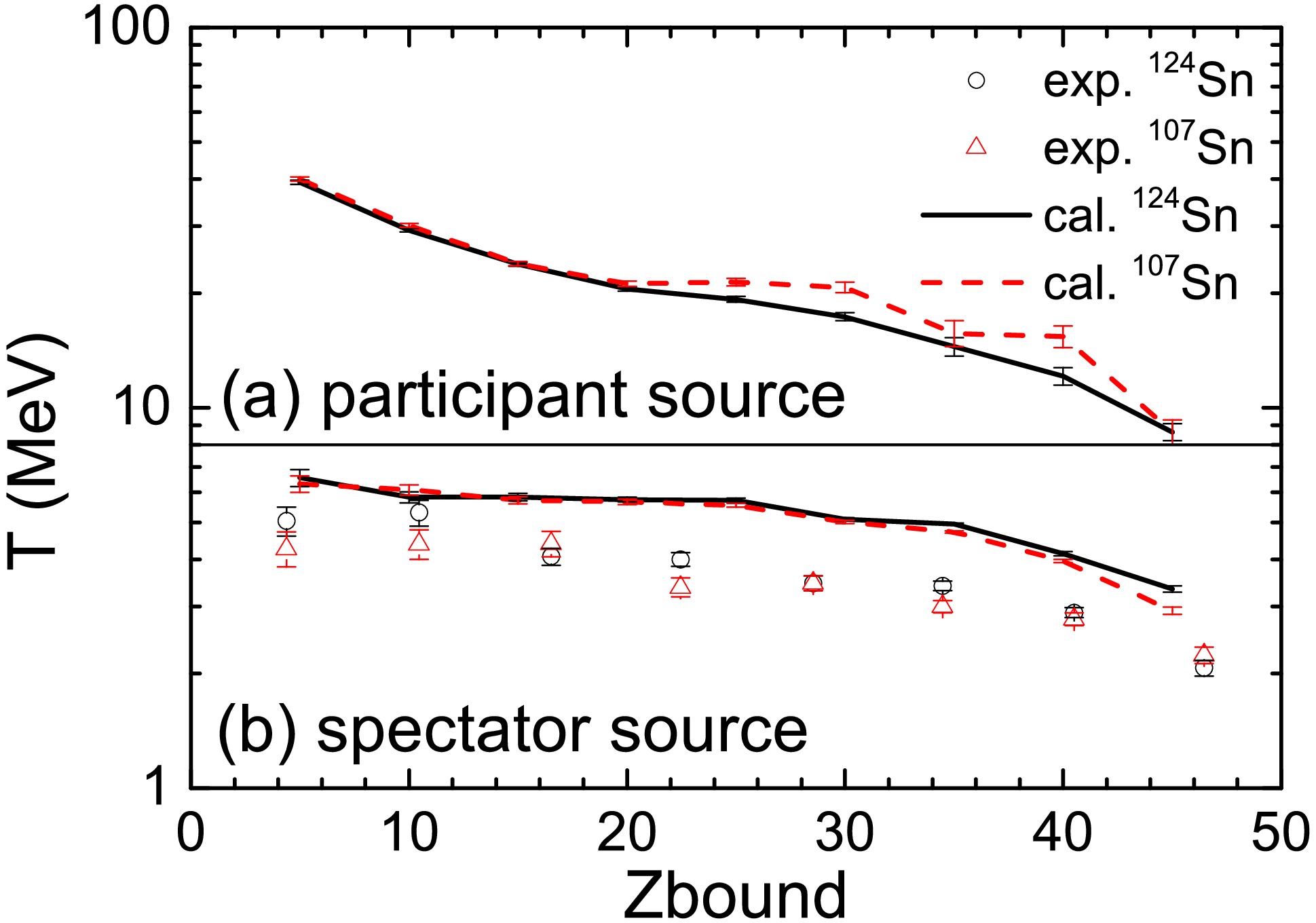

(9) When applying this formula to fit the calculated neutron spectra of the transverse momentum by the IQMD+GEMINI model, we extracted the respective temperatures of participant and spectator sources, as shown in Fig. 9. It should be noted that we employed a constraint of

$ 600 \, \text{MeV}/c < p_z < 1500 \, \text{MeV}/c $ to enhance statistical significance.

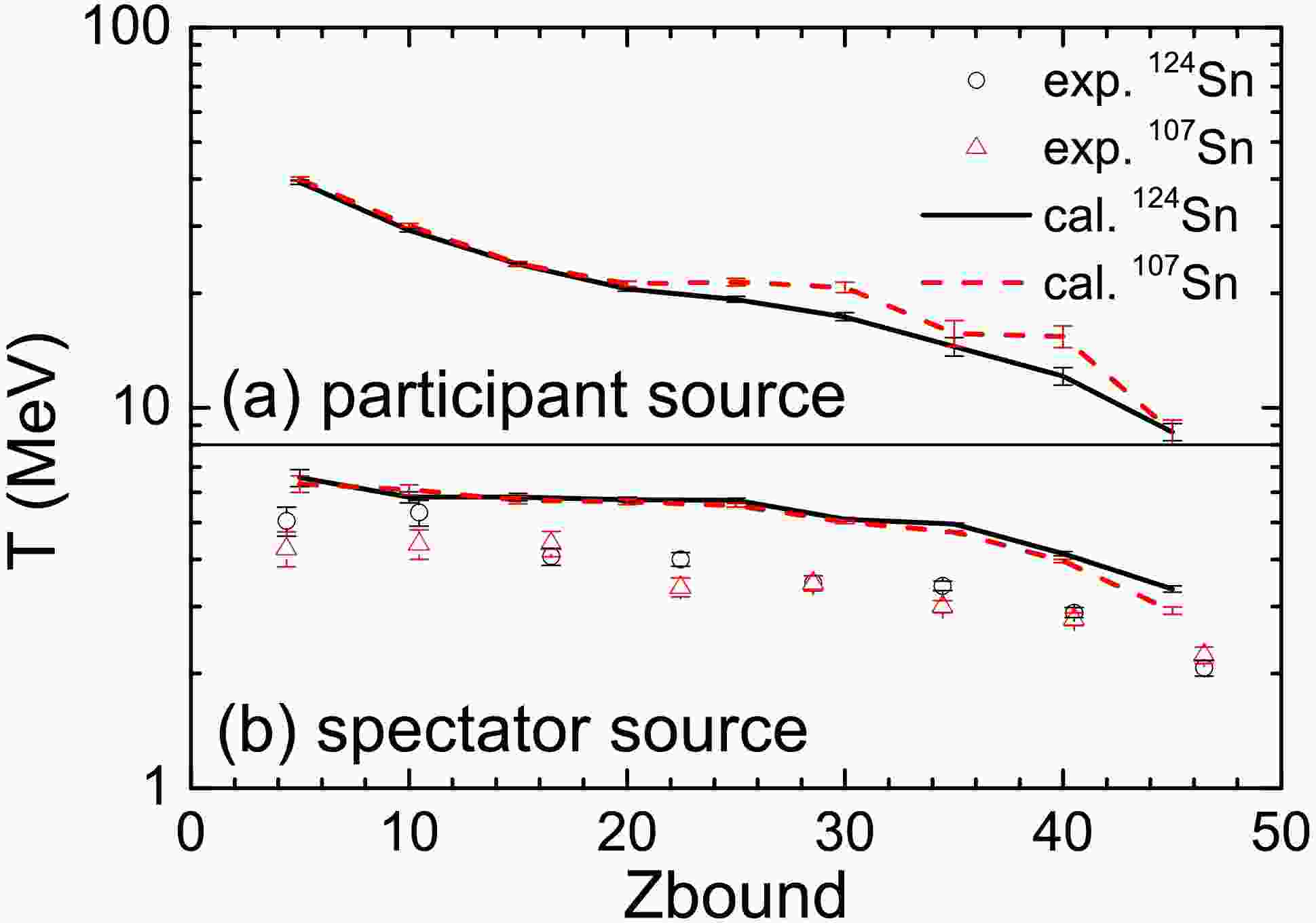

Figure 9. (color online) Temperatures of the participant and spectator sources as a function of

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ in 107,124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. The temperatures extracted from the experimental neutron spectra are taken from Ref. [21].Figure 9 shows that the participant sources exhibit anomalously higher temperatures than the spectator sources. This indicates that the IQMD+GEMINI model overestimates both the temperature of the participant source or their contribution to neutron spectra in the detection region, which ultimately explains the anomalous neutron spectra predictions by the model (see Fig. 8). In previous analyses, we have pointed out that the model overestimates the temperature of emission sources, consequently leading to an underestimation of detector efficiency. Those results echo the findings presented in Fig. 9. The in-medium cross sections and methods for handling the Pauli blocking used in the model play a critical role in describing neutron emission during the violent collision stage. Future studies could explore various parameterizations of in-medium modifications to investigate their effects on neutron energy spectra.

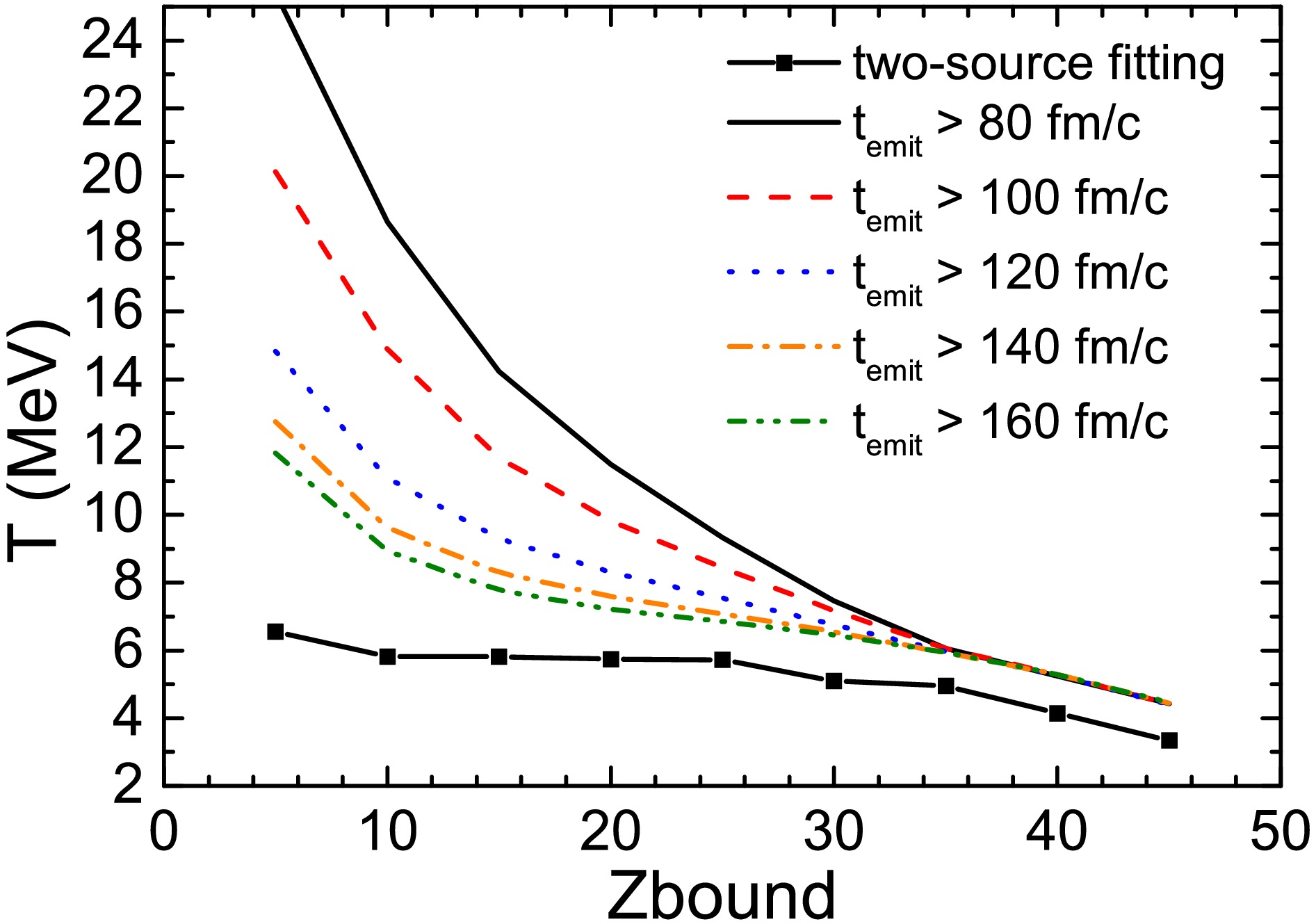

The variations in spectator-temperature with

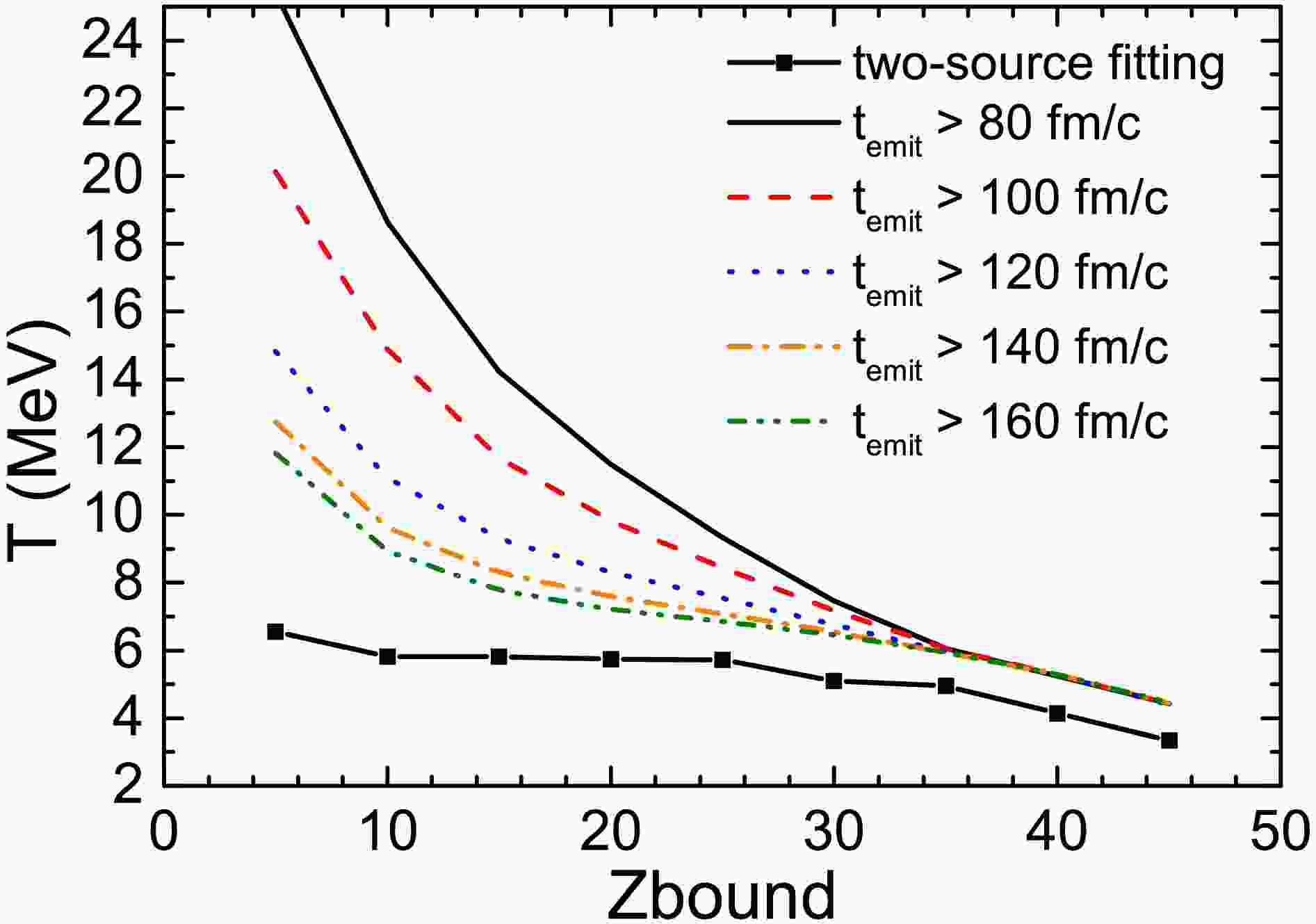

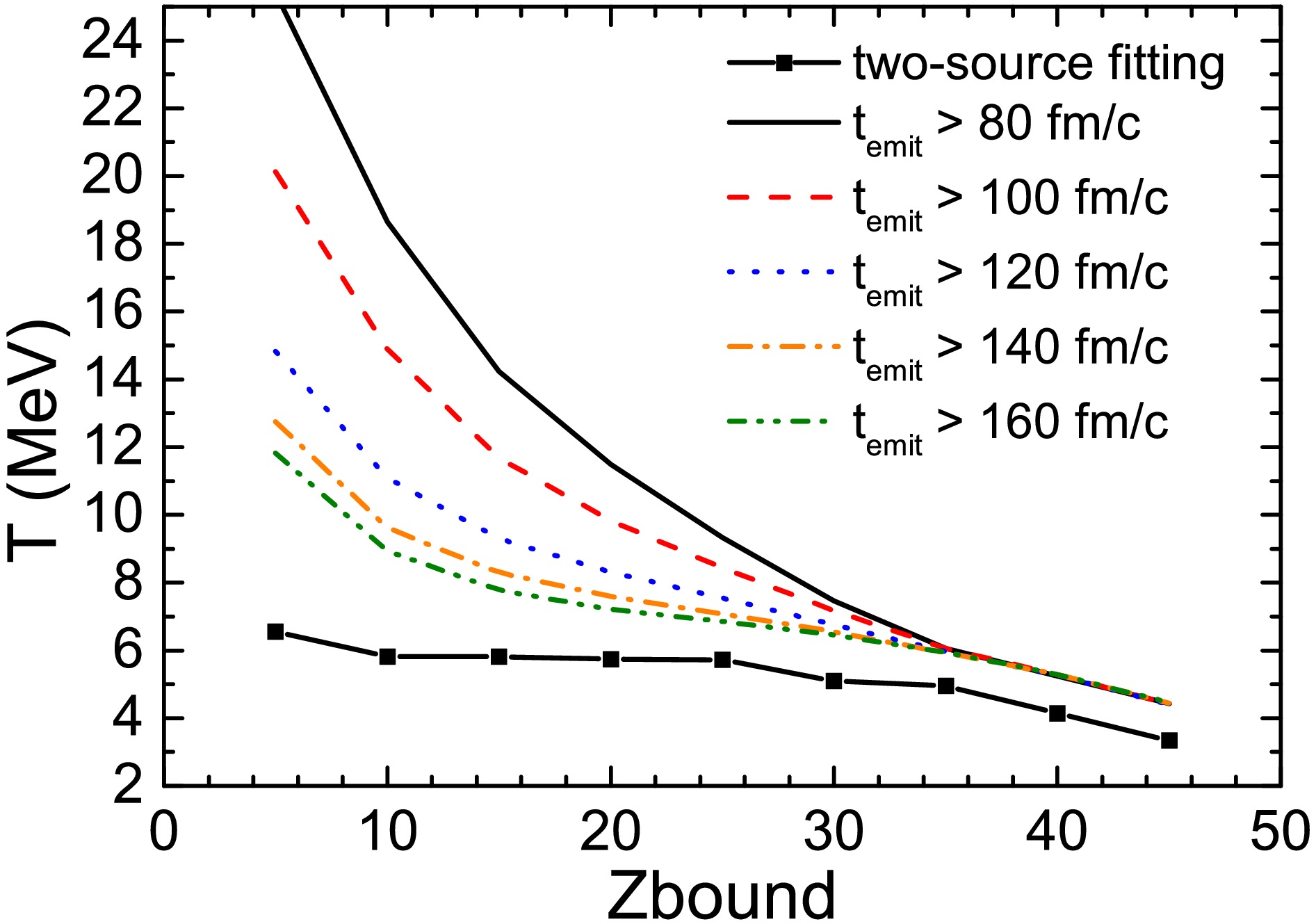

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ , extracted from the theoretical momentum distributions, are compared with the data in Fig. 9(b). The experimental data are represented by open circles for the$ ^{124}\text{Sn} $ system and open triangles the$ ^{107}\text{Sn} $ system, while the IQMD+GEMINI model calculations are shown as curves and dashed lines, respectively. The temperature displays a weak isospin effect, where the temperature of the$ ^{124}\text{Sn} $ system is slightly higher than that of the$ ^{107}\text{Sn} $ system. This result is consistent with findings in Ref. [18], and the specific reasons will not be elaborated here.To extract the temperature of the spectator source, we primarily relied on the two-source Maxwellian fitting formula (Eq. (9)) because, in experiments, the participant and spectator neutrons cannot be separated on an event-by-event basis. This approach is therefore a necessary approximation when analyzing measured spectra that contain contributions from both sources. Within the IQMD+GEMINI framework, however, it is possible to examine the time sequence of neutron emission. Early-emitted neutrons are largely associated with the hot participant region, whereas later emissions increasingly reflect the cooler spectator source. By applying successive time gates (80,100,120,140, and 160 fm/c), we extracted the transverse momentum spectra of neutrons emitted after each cutoff time and fitted them with the single-source Maxwellian distribution (Eq. (8)). The corresponding temperatures, denoted as Ts(t), are shown in Fig. 10 and compared with those relied on the two-source Maxwellian fitting formula (Eq. (9)). The values of Ts(t) decrease systematically with increasing emission time, consistent with the physical expectation that the spectator source is cooler than the participant source. For later times ( e.g., 160 fm/c), Ts(160 fm/c) approaches Ts, differing by approximately 1 MeV. This residual difference may arise from a small admixture of participant neutrons even at late times, or from the intrinsic systematic uncertainty of the two-source fitting procedure. Nevertheless, the consistency between Ts(160 fm/c) and Ts strongly supports the validity of the two-source fitting method.

Figure 10. (color online) Temperatures of the spectator sources as a function of

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ in 124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. The temperature obtained from the two-source fit are compared with the temperature obtained from the single-source fit but the neutrons are selected by applying successive time gates (80,100,120,140, and 160 fm/c).It should be emphasized that the time-gating procedure is only applicable in transport model simulations, since neutron emission times are not accessible in experiments. For this reason, in the following analysis, we continue to use the spectator temperature extracted from the two-source Maxwellian fit as the experimentally relevant observable.

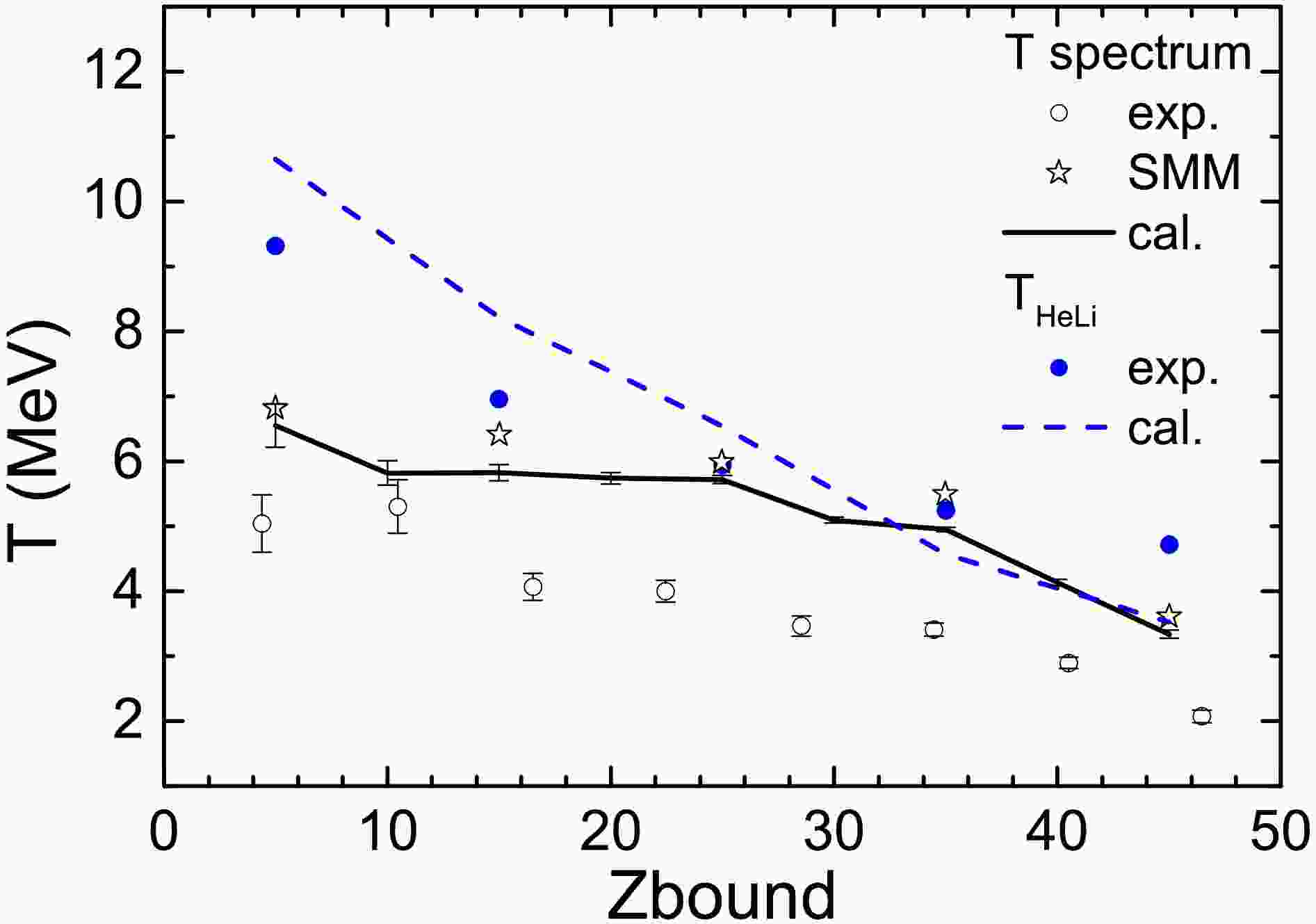

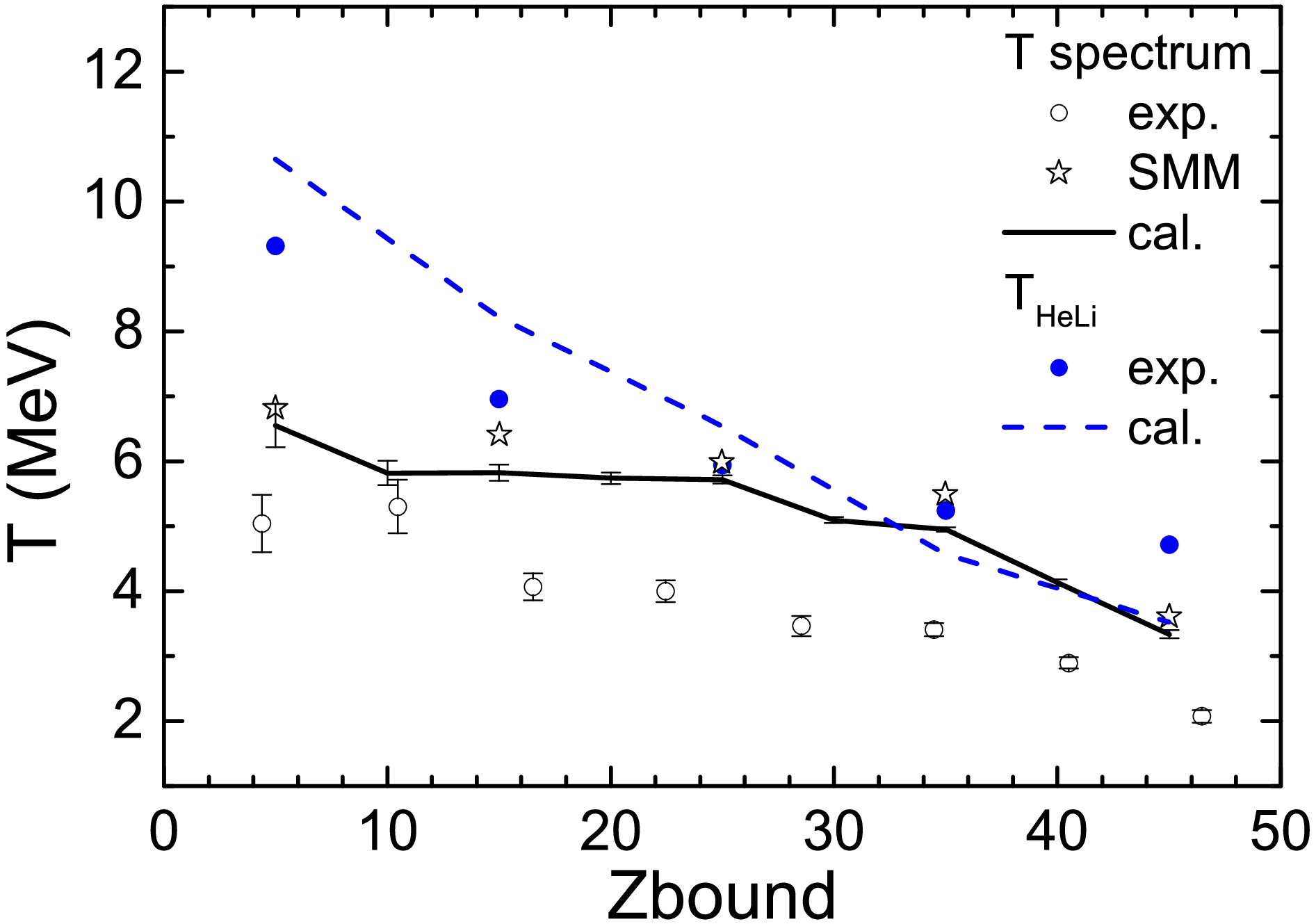

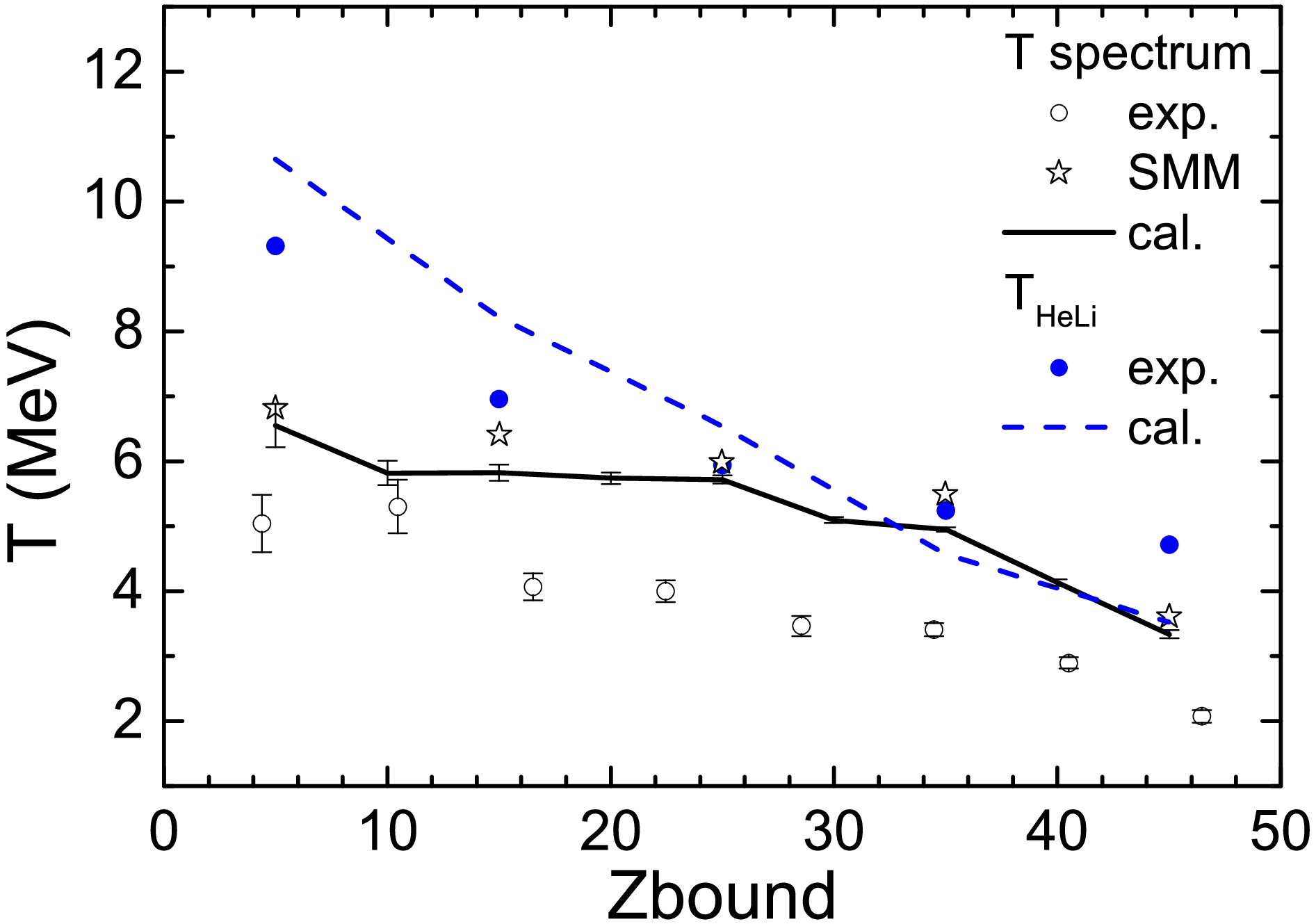

Figure 11 shows the temperatures of the spectator sources as a function of

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ in the 124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. Two different thermometers are applied to extract the temperatures. One is the spectrum thermometer, i.e. the temperature is extracted by fitting the neutron spectra, and the other is the isotopic thermometer$ T_{\rm HeLi}=1.33 {\rm MeV} / \ln (\frac{Y_{^{6}{\rm Li}}/Y_{^{7}{\rm Li}}}{Y_{^{3}{\rm He}}/Y_{^{4}{\rm He}}}) $ , where$ Y_{^{6}{\rm Li}} $ ,$ Y_{^{7}{\rm Li}} $ ,$ Y_{^{3}{\rm He}} $ ,$ Y_{^{4}{\rm He}} $ are the yields of fragments$ ^{6}{\rm Li} $ ,$ ^{7}{\rm Li} $ ,$ ^{3}{\rm He} $ ,$ ^{4}{\rm He} $ , respectively. For the spectrum thermometer, the experimental data are shown as open circles, the mean microcanonical temperature of the SMM description are shown as starts, and the temperatures extracted by the IQMD+ GEMINI model are shown as a curve. The temperatures by the IQMD+GEMINI model are higher than the experimental data but are closer to that by the SMM model. The authors in Ref. [21] refer to the partly large errors of the data and interpret the lower temperatures as properties of secondary emissions with neutrons dominating in the later stages. The secondary effects have been considered in the IQMD+GEMINI model. However, the temperature by the IQMD+GEMINI still exhibits a marked discrepancy from experimental values. The contributions of neutrons from the participant source deserves attention.

Figure 11. (color online) Temperatures of the spectator sources as a function of

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ in 124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. The temperatures extracted from the experimental neutron spectra are shown as open circles and those calculated by the SMM model are shown as stars. These values are taken from Ref. [21]. Temperatures extracted by fitting the neutron spectra with Eq. (9) are shown as curve. The isotopic temperatures$ T_{\text{HeLi}} $ are shown. Those extracted from experimental data in Ref. [18] are shown as (blue) circles, while that predicted by the IQMD+GEMINI model are shown as a (blue) dashed curve.For the isotopic thermometer, rather than the overall overestimation, a similar trend is observed when comparing the calculated temperatures by the IQMD+GEMINI model (blue dashed curve) to the experimental data (blue circles). The calculated temperatures overestimate the experimental data by about 1.3 MeV in the small

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ region, and underestimate by 1.2 MeV for$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ = 45. Such discrepancies between different thermometric methods arise because the isotope thermometer probes the thermal state at chemical freeze-out, while the spectrum thermometer measure kinematic signatures. The latter may be contaminated by the non-equilibrium effect, as mention in Ref. [39]. Figure 11 shows that discrepancies between different temperatures are even greater for the small$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ region. The violent collisions cause a longer equilibrium time for the participants, i.e., the non-equilibrium effect is more obvious. -

The 107,124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon is simulated by the IQMD+GEMINI model. The fragments with Z = 3 and neutrons are applied to extracted the fragmenting source. Figure 1 shows the two-dimensional distribution of transverse and longitudinal momentum for Z = 3 fragments. Two distinct emission sources are apparent in the figure: a target-like source around

$ p_z $ = 0 and a spectator source near$ p_z $ = 1200 MeV/c. The distribution's hot spot center lies at a transverse momentum of 50 MeV/c, corresponding to a transverse kinetic energy of 1.3 MeV. This recoil kinetic energy is influenced by both the emission source recoil and Coulomb repulsion of the fragments

Figure 1. (color online) Distribution of fragments with Z=3 in the plane of transverse momentum p

$ _{t} $ versus longitudinal momentum p$ _{z} $ for 124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. The blue lines emitting angles in the laboratory frame. The values 10.2° and 4.5° are the maximum acceptance of the ALADIN forward spectrometer in the horizontal direction and in the vertical direction, respectively. TheThe blue line in the figure represents the emission angle of the fragments in the laboratory system. The acceptance range of the ALADIN spectrometer covers areas with horizontal angle less than 10.2° and vertical angle less than 4.5 °. In the Ref. [21], the horizontal and vertical axes are designated as

$ y $ and$ x $ , respectively, with the beam direction defined as$ z $ . In the experiment, it is not possible to explicitly identify the collision parameter direction. Instead, the horizontal ($ y $ ) and vertical ($ x $ ) directions are defined by the detector orientation. This axis definition differs from theoretical studies, where the beam incidence direction is typically denoted as$ z' $ , the collision parameter direction as$ x' $ , and the perpendicular direction as$ y' $ . However, this discrepancy does not affect our analysis due to the relatively small recoil kinetic energy. Given the small recoil kinetic energy, the fragment emission shows axial symmetry along the$ z $ -axis. Thus variations in Cartesian coordinate definitions within the plane perpendicular to$ z $ do not impact the dynamic analysis.The ALADIN spectrometer is designed to detect most of the fragments from spectator sources while excluding most of the those from the target-like emission sources. The horizontal acceptance angle of 10.2° is large enough to collect most fragments from the spectator sources, while the vertical acceptance angle of 4.5° is not enough. Some fragments with Z = 3 have emission angles greater than 4.5° are not detected. This issue is more clearly illustrated by the angular distribution shown in Fig. 2. In the figure, the blue box represents the acceptance region of the ALADIN spectrometer, which extends

$ \pm $ 10.2° horizontally and$ \pm $ 4.5° vertically.

Figure 2. (color online) Probability distribution with respect to the beam direction of the fragment with Z=3 produced in 124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. The blue square represents the acceptance-area of the ALADIN detector.

In Ref. [19], it is reported that the ALADIN spectrometer captures 90% of Z = 3 fragments. However, our calculations indicate a efficiency of only 74%. This discrepancy is largely due to the recoil effect from the emission source, which impacts the vertical acceptance angle, though the horizontal acceptance angle is sufficiently large. Some fragments escape detection along the horizontal axis. The deviation between experimental and calculated reception efficiencies also stems from an overestimation of the emitter temperature in the IQMD+GEMINI model used for simulations. It should be noted that the reception efficiency increases with the mass number of the emission source, eventually approaching 100% for heavier sources. Therefore, this deviation has a minimal effect on the subsequent discussion of the value of the bounding charge

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ .Figure 3 shows distribution of neutrons in the plane of transverse momentum p

$ _{t} $ versus longitudinal momentum p$ _{z} $ . Neutrons near$ p_z $ = 0 originate from the target-like system, while those near$ p_z $ = 1200 MeV/c come from the projectile-like system. A significant number of neutrons are also distributed over a broad range around$ p_z $ = 600 MeV/c, which are emitted from the participants that acquire substantial transverse momentum due to the intense collision dynamics.

Figure 3. (color online) Distribution of neutrons in the plane of transverse momentum p

$ _{t} $ versus longitudinal momentum p$ _{z} $ for 124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. The blue lines show emitting angles in the laboratory frame. The values 8.72° and 4.09° are the maximum acceptance of the LAND in the horizontal direction and in the vertical direction, respectively.Neutrons can be emitted throughout the entire heavy-ion collision process, from the pre-equilibrium stage (characterized by violent two-body collisions), to the high-temperature stage of multi-fragmentation, and finally to the lower-temperature stage of secondary decay. In contrast, the Z = 3 fragments (shown in Fig. 1) primarily originate from the multi-fragmentation stage. This results in a wider kinetic energy distribution for the neutrons compared to the Z = 3 fragments.

The blue line in the figure represents the neutron emission angle. It is shown in Ref. [21] that the maximum horizontal acceptance angle of the LAND is 8.72°, and the maximum vertical acceptance angle is 4.09°. It is clear that the LAND can effectively exclude most neutrons from both the target-like and participant systems.

Figure 4 shows the angular distribution of neutrons in the detector's receiving plane. The blue box represents the LAND's acceptance region. The center of the neutron distribution is at the origin, and the distribution is circular. The LAND covers the angular range 0

$ < $ $ \theta_x $ $ < $ 8.72$ ^\circ $ and -4.09$ ^\circ $ $ < $ $ \theta_y $ $ < $ 4.09$ ^\circ $ . The detector does not cover the region where$ \theta_x > 0^\circ $ . However, due to the symmetry of the system, this limitation does not adversely affect the results. In Ref. [21], a neutron emission source with a temperature of 4 MeV was studied, and it was found that LAND's acceptance for neutrons is 42.4%. However, the model calculations show that the LAND's acceptance is lower than this value for neutrons emitted by the bystander emission sources in the reaction. The lower of the reception efficiency by the IQMD+GEMINI model is caused by the overestimation of the temperature.

Figure 4. (color online) Probability distribution with respect to the beam direction of neutron produced in 124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. The blue square represents the acceptance-area of the LAND.

The energy spectrum of neutrons with emission angles less than 2° has been measured in Ref. [21]. The calculated energy spectrum by the IQMD+GEMINI model is compared with the experimental data in Figure 5. The dashed line in the figure represents an incident energy of 600 MeV/u. Both the experimental and calculated spectra show a peak of the differential cross section at 600 MeV/u, indicating that neutrons emitted at angles less than 2° primarily originate from projectile-like emission sources, with a minimal recoil effect.

Figure 5. (color online) Inclusive differential cross section of neutrons in the laboratory detected within the solid angle

$ \theta_{lab} $ $ < $ 2° for the 107,124Sn + 120Sn collisions at 600 MeV/nucleon. The experimental data are taken from Ref. [21].The experimental energy spectra for the

$ ^{124} \text{Sn} $ and$ ^{107} \text{Sn} $ systems have similar shapes, but the cross section for the$ ^{124} \text{Sn} $ system is slightly larger than that for$ ^{107} \text{Sn} $ . For the$ ^{124} \text{Sn} $ system, the peak value is 21.7 mb/MeV, while for the$ ^{107} \text{Sn} $ system, the peak value is 4.3 mb/MeV. The calculations capture the overall shape and system dependence of the experimental energy spectrum: the peak occurs at 600 MeV, and the peak for the$ ^{124} \text{Sn} $ system is larger than that for the$ ^{107} \text{Sn} $ system. However, the energy spectrum predicted by the model is somewhat narrower than the experimental spectrum.The GEANT4 toolkit was used in Ref. [21] to simulate a

$ ^{124}\text{Sn} $ beam at 600 MeV/u incident on a 0.5 mm thick Sn target, calculating neutron multiplicity as a function of$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ , as shown by the dots in Fig. 6. The GEANT4 simulations employ the Bertini cascade model. In the calculations, neutrons emitted from secondary de-excitations of target fragments were excluded by applying the condition$ E_{\text{lab}} $ $ > $ 100 MeV. Following this criterion, we obtained the neutron multiplicity as a function of$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ from the IQMD+GEMINI model, represented by the blue curve in Fig. 6.

Figure 6. (color online) Neutron multiplicity as a function of

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ for 124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. The circles are the calculations by the Bertini cascade implemented in GEANT4 taken from Ref. [21].In the range 20

$ < $ $ Z_{\text{bound}} $ $ < $ 45, the IQMD+GEMINI model and the Bertini cascade model yield closely matching results. Differences appear, however, in peripheral and central collision regions. For peripheral collisions, the neutron multiplicity predicted by the Bertini cascade model is lower than that predicted by the IQMD+GEMINI model. At$ Z_{\text{bound}} = 50 $ , the cascade model gives a neutron multiplicity of 4, while the IQMD+GEMINI model predicts 11. This discrepancy reflects differences in the predicted isotopic distribution of Sn fragments: the IQMD+GEMINI model suggests more neutron-deficient isotopes. If only quasi-projectile fragments are considered, the maximum$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ should be 50. However, the cascade model shows calculation even for$ Z_{\text{bound}} > 50 $ , possibly due to the method for selecting quasi-projectile fragments.In central collisions, neutron multiplicity steadily increases as

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ decreases. For instance, at$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ = 2, the cascade model predicts a neutron multiplicity near 80, while the IQMD+GEMINI model suggests a higher count, reaching 91 free neutrons. Notably, using$ E_{\text{lab}} $ $ > $ 100 MeV to filter for neutrons from projectile fragmentation is not the optimal method. As shown in Fig. 3, the single-nucleon momentum of the projectile is approximately 1200 MeV/c in the experimental frame. Applying a transverse momentum filter of$ p_z $ $ > $ 600 MeV/c more effectively selects neutrons originating from projectile fragmentation.The neutron multiplicity filtered by

$ p_z $ $ > $ 600 MeV/c is depicted by the red curve in Fig. 6. This criterion selects fewer neutrons than the$ E_{\text{lab}} $ $ > $ 100 MeV threshold. At$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ = 2, neutron multiplicity reaches 59, indicating that for central collisions, 59 of the 70 neutrons in the$ ^{124}\text{Sn} $ projectile are released as free neutrons, while the remaining 11 are emitted as deuterons or tritons.In fact, the neutrons selected using the condition

$ p_z $ $ > $ 600 MeV/c do not originate from a single equilibrated thermal source. During the early stages of projectile-target collisions, neutrons are emitted from one side of the projectile due to intense collisions. These neutrons are associated with the participant zone and exhibit a higher temperature. After the violent collision process ends, part of the projectile is sheared off, leaving an excited remnant (i.e., the spectator source), which de-excites through nucleon emission and multi-fragmentation. By isolating this subset of neutrons, the momentum distribution of the neutrons can provide insights into the spectator source characteristics. In Ref. [21], the condition 1000 MeV/c$ < $ $ p_z $ $ < $ 1500 MeV/c is used to select neutrons originating from the spectator source. We used the same method to extract neutrons originating from the spectator source. Figure 7 shows the experimental and theoretical neutron multiplicity as a function of$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ . Experimental data indicate that as$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ increases, the neutron multiplicity first rises and then falls. This trend is similar to the variation in intermediate-mass fragment (IMF) multiplicity with$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ . For events around$ Z_{\text{bound}} \approx 30 $ , the spectator source primarily undergoes multifragmentation during de-excitation, leading to the emission of a larger number of neutrons. In contrast, for events with smaller or larger$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ , the spectator source is either smaller or has lower excitation energy, resulting in fewer emitted neutrons.

Figure 7. (color online) Neutron multiplicity of the projectile source as a function of

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ for 107,124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. The neutrons from the projectile source are sorted by$ 1000 \, \text{MeV}/c < p_z < 1500 \, \text{MeV}/c $ The experimental data are taken from Ref. [21].Comparing the results for the

$ ^{124}\text{Sn} $ and$ ^{107}\text{Sn} $ projectiles reveals that$ ^{124}\text{Sn} $ leads to a neutron-rich spectator, producing higher neutron multiplicity. Conversely,$ ^{107}\text{Sn} $ results in a neutron-deficient spectator, yielding lower neutron multiplicity. However, the difference in neutron multiplicity between the two systems is approximately 4, which is smaller than the neutron number difference of 17 between$ ^{124}\text{Sn} $ and$ ^{107}\text{Sn} $ . This suggests that during the violent collision stage, before the formation of the equilibrated spectator source, the excess neutrons in$ ^{124}\text{Sn} $ are largely emitted, causing the neutron multiplicities of the spectator sources in both systems to converge.Comparing the IQMD+GEMINI model calculations with experimental data shows a high degree of consistency. Combined with the multiplicity observables reported in the literature, we can conclude that the IQMD+GEMINI model accurately captures the primary features of the collision dynamics in

$ ^{124}\text{Sn} + ^{120}\text{Sn} $ reactions. This provides a reliable foundation for the subsequent analysis of the spectator source temperature.We adopted the same method and calculated the transverse momentum distribution of these neutrons, as shown in Fig. 8. The full circles is the experimental data. The (blue) open circles and (red) open square are the calculated distributions of

$ p_{y} $ and$ p_{x} $ , respectively. The neutron density distribution in the$ p_{y} $ vs$ p_{x} $ plane is assumed to be classical Maxwellian function added to a constant background pedestal.

Figure 8. (color online) Distribution of transverse momentum for neutrons from the fragmentation of 124Sn projectiles, selected with the condition

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ $ \geqslant $ 45. The full circles and the dotted curve are the experimental data and corresponding fit. The (blue) open circles and (red) open square are the calculated distributions of$ p_{x} $ and$ p_{y} $ , respectively. The corresponding fits are shown as (blue) curve and (red) dash. The data are taken from Ref. [21].$ \begin{aligned} \frac{\partial^{2}N}{\partial p_{x}\partial p_{y}} = C_{1} \exp\left(-\frac{p_{x}^{2}+p_{y}^{2}}{2mT^{2}}\right) +C_{2}. \end{aligned} $

(8) where

$ m $ is the neutron mass,$ C_{1} $ and$ C_{2} $ are the fitting parameters,$ T $ is the temperature parameter. To find the temperature parameter, the distribution of$ p_{x} $ (or$ p_{y} $ ) is fitted. The fit of experimental data with a Gaussian distribution corresponding to$ T $ = 2.04 MeV superimposed on a constant background is represented by the dotted line. The cases for the calculated$ p_{x} $ and$ p_{y} $ distributions are shown as (blue) curve and (red) dash. The corresponding temperature parameters are$ T_{x} $ = 3.37 MeV and$ T_{y} $ = 3.31 MeV, which are significantly higher than the experimental value.A key issue in the figure is why the theoretical transverse momentum distribution exhibits a certain broadening compared to experimental data. In other words, why the temperatures extracted from neutron momentum distributions calculated by the IQMD+GEMINI model are overall higher than the experimental data. In fact, the neutron emission actually comprises two distinct sources, the participant and spectator sources. The constant

$ C_{2} $ in Equation 8 describes this two-source effect, where the participant source is assumed to contribute a small amount of and temperature-independent neutrons to the detection region. If the model overestimates contributions of neutrons from the participant source, the fitting formula 8 will not be applicable to the theoretical spectra.By replacing constant

$ C_{2} $ with a Maxwellian distribution and considering the recoil effect of the spectator source, we derive the following neutron distribution formula:$ \begin{aligned} \frac{\partial^{2}N}{\partial p_{x}\partial p_{y}} = C_{1} \exp\left[-\frac{(p_{x}-p_{x0})^{2}+p_{y}^{2}}{2mT_{s}^{2}}\right] +C_{2}\exp\left(-\frac{p_{x}^{2}+p_{y}^{2}}{2mT_{p}^{2}}\right). \end{aligned} $

(9) When applying this formula to fit the calculated neutron spectra of the transverse momentum by the IQMD+GEMINI model, we extracted the respective temperatures of participant and spectator sources, as shown in Fig. 9. It should be noted that we employed a constraint of

$ 600 \, \text{MeV}/c < p_z < 1500 \, \text{MeV}/c $ to enhance statistical significance.

Figure 9. (color online) Temperatures of the participant and spectator sources as a function of

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ in 107,124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. The temperatures extracted from the experimental neutron spectra are taken from Ref. [21].Figure 9 shows that the participant sources exhibits anomalously higher temperatures than the spectator sources. This indicates that the IQMD+GEMINI model overestimates both the temperature of participant source or their contribution to neutron spectra in the detection region, which ultimately explains the anomalous neutron spectra predictions by the model (see Fig. 8). In previous analyses, we have pointed out that the model overestimates the temperature of emission sources, consequently leading to an underestimation of detector efficiency. Those results echoes the findings presented in Figure 9. The in-medium cross-sections and methods for handling the Pauli blocking used in the model play a critical role in describing neutron emission during the violent collision stage. Future studies could explore various parameterizations of in-medium modifications to investigate their effects on neutron energy spectra.

The variation of spectator-temperature with

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ , extracted from the theoretical momentum distributions, are compared with the data in Fig. 9(b). The experimental data are represented by open circles for the$ ^{124}\text{Sn} $ system and open triangles the$ ^{107}\text{Sn} $ system, while the IQMD+GEMINI model calculations are shown as curves and dashed lines respectively. The temperature display a weak isospin effect, where the temperature of the$ ^{124}\text{Sn} $ system is slightly higher than that of the$ ^{107}\text{Sn} $ system. This result is consistent with findings in Ref. [18], and the specific reasons will not be elaborated here.To extract the temperature of the spectator source, we primarily relied on the two-source Maxwellian fitting formula (Eq. 9), since in experiments the participant and spectator neutrons cannot be separated on an event-by-event basis. This approach is therefore a necessary approximation when analyzing measured spectra that contain contributions from both sources. Within the IQMD+GEMINI framework, however, it is possible to examine the time sequence of neutron emission. Early-emitted neutrons are largely associated with the hot participant region, whereas later emissions increasingly reflect the cooler spectator source. By applying successive time gates (80,100,120,140, and 160 fm/c), we extracted the transverse momentum spectra of neutrons emitted after each cutoff time and fitted them with the single-source Maxwellian distribution (Eq. 8). The corresponding temperatures, denoted as Ts(t), are shown in Fig. 10 and compared with those relied on the two-source Maxwellian fitting formula (Eq. 9). The values of Ts(t) decrease systematically with increasing emission time, consistent with the physical expectation that the spectator source is cooler than the participant source. For later times (e.g., 160 fm/c), Ts(160 fm/c) approaches Ts, differing by about 1 MeV. This residual difference may arise from a small admixture of participant neutrons even at late times, or from the intrinsic systematic uncertainty of the two-source fitting procedure. Nevertheless, the consistency between Ts(160 fm/c) and Ts strongly supports the validity of the two-source fitting method.

Figure 10. (color online) Temperatures of the spectator sources as a function of

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ in 124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. The temperature obtained from the two-source fit are compared with the temperature obtained from the single-source fit but select the neutrons by applying successive time gates (80,100,120,140, and 160 fm/c).It should be emphasized that the time-gating procedure is only applicable in transport model simulations, since neutron emission times are not accessible in experiments. For this reason, in the following analysis we continue to use the spectator temperature extracted from the two-source Maxwellian fit as the experimentally relevant observable.

Figure 11 shows the temperatures of the spectator sources as a function of

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ in 124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. Two different thermometers are applied to extracted the temperatures. One is the spectrum thermometer, i.e. the temperature is extracted by fitting the neutron spectra, and the other is the isotopic thermometer$ T_{HeLi}=1.33 MeV / \ln (\frac{Y_{^{6}Li}/Y_{^{7}Li}}{Y_{^{3}He}/Y_{^{4}He}}) $ , where$ Y_{^{6}Li} $ ,$ Y_{^{7}Li} $ ,$ Y_{^{3}He} $ ,$ Y_{^{4}He} $ are the yields of fragments$ ^{6}Li $ ,$ ^{7}Li $ ,$ ^{3}He $ ,$ ^{4}He $ , respectively. For the spectrum thermometer, the experimental data are shown as open circles, the mean microcanonical temperature of the SMM description are shown as starts, and the temperatures extracted by the IQMD+GEMINI model are shown as curve. The temperatures by the IQMD+GEMINI model are higher than the experimental data but is more close to that by the SMM model. The authors in Ref. [21] mentioned the partly large errors of the data, and provide an interpretation of the lower temperatures as properties of secondary emissions with neutrons dominating in the later stages. The secondary effects have been considered in the IQMD+GEMINI model. However, the temperature by the IQMD+GEMINI still exhibits a marked discrepancy from experimental values. The contributions of neutrons from the participant source deserves attention.

Figure 11. (color online) Temperatures of the spectator sources as a function of

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ in 124Sn + 120Sn collision at 600 MeV/nucleon. The temperatures extracted from the experimental neutron spectra are shown as open circles, those calculated by the SMM model are shown as starts. Those values are taken from Ref. [21]. In this work, temperatures are extracted by fitting the neutron spectra with Eq. (9), and shown as curve. The isotopic temperatures$ T_{\text{HeLi}} $ are shown. Those extracted from experimental data in Ref. [18] are shown as (blue) circles, while that predicted by the IQMD+GEMINI model are as (blue) dashed curve.For the isotopic thermometer, rather than the overall overestimation, the similar trend is observed when comparing the calculated temperatures by the IQMD+GEMINI model (blue dashed curve) to the experimental data (blue circles). The calculated temperatures overestimate the experimental data by about 1.3 MeV in the small

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ region, and underestimate by 1.2 MeV for$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ = 45. Such discrepancies between different thermometric methods arise because the isotope thermometer probe the thermal state at chemical freeze-out, while the spectrum thermometer measure kinematic signatures. The latter may be contaminated by the non-equilibrium effect, as mention in Ref. [39]. Figure 11 shows that discrepancies between different temperatures are is even greater for the small$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ region. The violent collisions led to a longer equilibrium time for the participants, i.e. the non-equilibrium effect is more obvious. -

In summary, the 107,124Sn + 120Sn collisions at 600 MeV/nucleon are studied by the IQMD+GEMINI model. The two-dimensional distribution of transverse and longitudinal momentum for fragments with Z = 3 and neutrons are applied to show the emission sources. It is shown that only target-like and projectile-like emission sources are apparent for the Z = 3 fragments, but the contribution of the participant source is considerable for neutrons. The recoil kinetic energy of the spectator source is minor compared to its kinetic energy near 600 MeV/nucleon.

The calculations of the differential cross section, multiplicity, and transverse momentum distribution of neutrons from the spectator source are campared with the data taken from Ref. [21]. The calculations show a high degree of consistency with the data of differential cross section and multiplicity as a function of the bounding charge. For the transverse momentum distribution, the calculations capture the Gaussian shape, but the calculated distribution width is larger than the experimental case. The neutron emission actually comprises two distinct sources, the participant and spectator sources. The theoretical distribution exhibits a broadening compared to the data because the model overestimates contributions of neutrons from the participant source.

Two-source parameterization is applied to fit the theoretical spectra of nuetrons. The extracted temperatures of the spectator sources agree with the SMM-derived temperatures within 0.5 MeV. However, the participant source exhibits anomalously high temperatures. Our work identifies the possible model-errors of the IQMD+GEMINI model when describing the neutron emission from the participant source, which is of reference for the further development of the model. The temperatures of the spectator sources extracted by two different thermometers are compared, one is the spectrum thermometer and the other is the isotopic thermometer. The discrepancies between different thermometric methods are observed. Particularly for the small

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ region, the isotopic temperatures are higher than the spectrum cases. The latter are shown to be contaminated by the non-equilibrium effect. -

In summary, the 107,124Sn + 120Sn collisions at 600 MeV/nucleon are studied by the IQMD+GEMINI model. The two-dimensional distribution of transverse and longitudinal momentum for fragments with Z = 3 and neutrons are applied to show the emission sources. It is shown that only target-like and projectile-like emission sources are apparent for the Z = 3 fragments, but the contribution of the participant source is considerable for neutrons. The recoil kinetic energy of the spectator source is minor compared to its kinetic energy near 600 MeV/nucleon.

The calculations of the differential cross section, multiplicity, transverse momentum distribution of neutrons from the spectator source are campared with the data taken from Ref. [21]. It is found that the calculations shows a high degree of consistency with the data of differential cross section and multiplicity as a function of the bounding charge. For the transverse momentum distribution, the calculations capture the Gaussian shape, but the calculated distribution width is larger than the experimental case. The neutron emission actually comprises two distinct sources, the participant and spectator sources. The theoretical distribution exhibits a broadening compared to the data because the model overestimates contributions of neutrons from the participant source.

Two-source parameterization is applied to fit the theoretical spectra of nuetrons. The extracted temperatures of the spectator sources agreement with the SMM-derived temperatures within 0.5 MeV. However, the participant source exhibits anomalously high temperatures. Our work suggests the possible model-errors of the IQMD+GEMINI model when describing the neutron emission from the participant source, which is of reference for the further development of the model. The temperatures of the spectator sources extracted by two different thermometers are compared, one is the spectrum thermometer and the other is the isotopic thermometer. The discrepancies between different thermometric methods are observed. Particularly for the small

$ Z_{\text{bound}} $ region, the isotopic temperatures are higher than the spectrum cases. It is indicated that the later are contaminated by the non-equilibrium effect.

Nuclear temperature of spectator source extracted by neutron spectra in 124Sn,107Sn + 120Sn collisions at 600 MeV/nucleon

- Received Date: 2025-04-24

- Available Online: 2026-01-15

Abstract: The properties of neutrons from spectator sources produced in 107,124Sn + 120Sn collisions at 600 MeV/nucleon are studied. The isospin-dependent quantum molecular dynamics (IQMD) model is used to describe the dynamical process of fragmentation, and the statistical model GEMINI is applied to simulate the secondary decay of the pre-fragments. The differential cross section and multiplicity of the neutrons emitted from the spectator source are used to prove the model's feasibility. The temperatures of the spectator source are extracted by two-source-fitting the transverse momentum distributions of the neutrons using the classical Maxwellian functions. The temperatures of the spectator sources extracted from calculations are consistent with the experimental data, those from the SMM model, and the isotopic temperature

Abstract

Abstract HTML

HTML Reference

Reference Related

Related PDF

PDF

DownLoad:

DownLoad: