-

As is well known, Einstein’s general relativity theory is non-renormalizable [1]. One of the most popular methods is to append all possible quadratic curvature invariants to the usual Einstein-Hilbert action [2], despite the existence of ghost-like modes in this theory. These terms constitute the so-called Einstein-Weyl (EW) gravity [3–5], which includes the most general Einstein-Hilbert action with quadratic curvature invariants. Subsequently, the non-Schwarzschild black hole (NSBH) solutions were recovered in four dimensional spacetime [3, 4], where they also satisfy the condition of the Ricci scalar (

R=0 ). Since the Ricci scalar R does not vanish in higher dimensional(n>4) spacetime, Lü et al. found only the perturbed numerical solutions in the EW gravity [6]. Employing the continued fraction method, Kokkotas et al. constructed a numerical black hole solution in an analytical form [7], and its Hawking radiation was discussed in Ref. [8]. Furthermore, some new solutions were derived in anti-de Sitter (AdS) spacetime [9, 10].Recently, charged black holes were derived in Refs. [11-13] by applying the four dimensional EW theory coupled with an electromagnetic field. According to the ‘seed’ solution, these solutions can be divided into two groups in the Einstein-Maxwell-Weyl (EMW) theory. Group I solutions correspond to the charged extension of the higher derivative curvature for a Schwarzschild black hole. In Group II, the solutions are constructed from the charged generalization of the NSBH solution. The thermodynamic properties of these charged black holes were investigated in Ref. [13].

The quasinormal modes (QNMs) of a black hole have been a hot research topic for decades. The concept of QNMs was introduced in 1957 by the work of Regge and Wheeler, who investigated the stability of black holes under small perturbations [14]. The study of QNMs is beneficial to the understanding of the structure of black hole spacetimes and could play an important role in the detection of gravitational waves and some fundamental symmetries for the gauge/gravity duality [15, 16]. To date, QNMs have been calculated either by Einstein’s general relativity theory coupled with Maxwell theory [17-19] or nonlinear electrodynamics [20–24], or by modified gravities [25–28]. The analysis of QNMs of the non-Schwarzschild black holes was performed in the EW gravity [29, 30], where the linear relation between QNM frequencies and the parameter

p=r0√2α was recovered. Inspired by these results, we evaluate the effect of the charge Q on the QNMs and the stability of charged black holes in the Einstein-Maxwell-Weyl gravity. We will calculate the QNMs by considering test massless and massive scalar field perturbations on the charged black holes, respectively.This paper is constructed as follows. We first review charged black hole solutions with an increase of charge Q in the EMW gravity in Section 2. Then, we provide a detailed discussion of QNM frequencies under test scalar field perturbations, including massless and massive scalar fields in Section 3. Finally, we provide concluding remarks in the fourth section.

-

The action of the Einstein-Weyl gravity, combined with the electromagnetic field, is given by [12, 13]

I=116πG∫d4x√−g[R−αCμνρσCμνρσ−κFμνFμν],

(1) where

Fμν=∇μAν−∇νAμ is the electromagnetic tensor. Here,Cμνρσ is the Weyl tensor and the trace-free part of the Riemann tensor with the form [31, 32]Cμνρσ=Rμνρσ−(gμ[ρRσ]ν−gν[ρRσ]μ)+13Rgμ[ρRσ]ν,

where the part within brackets surrounding the indices refers to the anti-symmetric part. To date, various attempts have been made to formulate the Weyl curvature hypothesis in a rigorous way. The simplest choice of a scalar constructed from the Weyl tensor is

CμνρσCμνρσ from Eq. (1).The equations of motion are obtained as [12, 13]

Rμν−12gμνR−4αBμν−2κTμν=0,∇μFμν=0,

(2) where

Bμν is the trace-free Bach tensor, andTμν is energy-momentum tensor of the Maxwell fieldBμν=(∇ρ∇σ+12Rρσ)Cμνρσ,Tμν=FαμFαν−14gμνFαβFαβ.

(3) We choose the metric ansatz

ds2=−N(r)e−2δ(r)dt2+1N(r)dr2+r2(dθ2+sin2θdφ2)

(4) with a metric function

N(r) equal to1−2m(r)/r . We constructed numerical charged black hole solutions withα=12 andκ=1 [13], according to two neutral scenarios: the Schwarzschild (SBH) and non-Schwarzschild black hole (NSBH) within the bound of0.363<r0<1.143 in the EW theory. Fig. 1 presents the relation between the mass M and Hawking temperature T for SBH and NSBH scenarios, where both neutral solutions coalesce atT≈0.091(r0≈0.876) . Taking Group I (Fig. 1(a)) as an example, charged black holes were constructed from the Schwarzschild black hole(Q=0) by increasing the charge Q while maintaining the same horizon radiusr0 . In particular, new charged black holes on both sides of the coalescent point exhibit different properties: as the charge Q increases, their mass becomes larger (smaller) depending on the temperature decrease (increase) on the left (right) hand side. A similar phenomenon is observed in Group II, as shown in Fig. 1(b). -

In this section, we consider the test massive scalar field

ψ propagating on charged black holes, which obeys the Klein-Gordon equation(◻−μ2)ψ=0,

(5) where

μ is the mass of the scalar field, andψ can be separated into spherical harmonics, temporal, and radial componentsψ(t,r,θ,ϕ)=∑lm1rΨl(r)Ylm(θ,ϕ)e−iωt,

(6) where

Ylm(θ,ϕ) is a usual spherical harmonic, and l is the angular harmonic index.Substituting Eqs. (4) and (6) into Eq. (5), we obtain the radial perturbed Schrödinger equation

(∂2r∗+ω2−Vl(r))Ψl(r)=0,

(7) where the effective potential is given as

Vl=l(l+1)Ne−2δr2+Ne−2δ(N′−Nδ′)r+μ2Ne−2δ

(8) and the tortoise coordinate

r∗ is adopted asdr∗dr=1Ne−δ.

(9) -

We consider the massless scalar field perturbation

(μ=0) in these charged black holes for Groups I and II. First, we choose appropriate boundary conditions. The respective boundary conditions at the black hole horizon and spatial infinity areΨl(r)∼{e−iωr∗∼(r−r0)−iω4πTr→r0(r∗→−∞)eiωr∗∼e−iωrr2Miωr→∞(r∗→∞),

(10) To derive these QN modes

ω , we employ the shooting method [33-35]. With the initial condition given by Eq. (10) at the event horizonr0 , we solve the perturbed Eq. (7) numerically for eachω using the Wolfram Mathematica® built-in function NDSolve forr0≤r≤rf , whererf≫r0 . This solution must also satisfy the boundary condition in Eq. (10) at spatial infinity, ifω is the quasinormal frequency.In the Tables 1–4, we present QNM frequencies (real and imaginary parts) for these charged black holes in Groups I and II. The QNM frequencies (for

l=0 and 1) of these neutral black holes (SBH and NSBH) are displayed in the first row of Tables 1–4. In the case ofQ→0 , the action presented in Eq. (1) becomes neutral [3, 4], recovering the Schwarzschild and non-Schwarzschild solutions in four dimensional spacetime. The fundamental QNM frequencies under a massless scalar field perturbation on the SBH background are given in Refs. [36, 37]. QNM frequencies (forl=0 and 1) of the NSBH with a horizon radiusr0>0.876 are provided in Refs. [29, 30]. However, for the NSBH withr0<0.876 , there is a discrepancy between QNM frequencies and data obtained from the relation expressionp∼ω in Ref. [30]. This is probably because this expression, derived in the bound0.876<r0<1.143 , is not valid in the region of0.363<r0<0.876 for the NSBH in the EW gravity.r0=0.5

r0=0.75

Q ω(l=0)

ω(l=1)

ω(l=0)

ω(l=1)

0 0.4420-0.4196i 1.1716-0.3908i 0.2947-0.2797i 0.7810-0.2605i 0.02 0.445730-0.419802i 1.17219-0.39126i 0.29504-0.284839i 0.781750-0.262508i 0.06 0.447649-0.423259i 1.17636-0.394006i 0.300096-0.291943i 0.768417-0.266851i 0.1 0.451833-0.431002i 1.18541-0.399437i 0.305035-0.307715i 0.795061-0.269681i 0.14 0.458975-0.443435i 1.19959-0.408586i 0.310574-0.309508i 0.806376-0.275657i 0.18 0.465102-0.456727i 1.21463-0.420002i 0.315876-0.317400i 0.820854-0.281226i 0.22 0.467173-0.461698i 1.23312-0.434605i 0.318256-0.328687i 0.825449-0.304661i 0.26 0.481790-0.486744i 1.25409-0.445270i 0.321404-0.342171i 0.830678-0.326003i 0.30 0.512190-0.519842i 1.27810-0.477936i 0.324608-0.355701i 0.834912-0.334916i 0.33 0.522566-0.532159i 1.29662-0.490691i 0.330838-0.369421i 0.838476-0.351239i Table 1. QNM frequencies of black holes within region of r0 < 0.876 in Group I.

r0=1.3

r0=2

Q ω(l=0)

ω(l=1)

ω(l=0)

ω(l=1)

0 0.1700-0.1614i 0.4506-0.1503i 0.1105-0.1049i 0.2929-0.0977i 0.02 0.169935-0.160131i 0.449981-0.149923i 0.110434-0.104754i 0.292409-0.0975053i 0.06 0.169604-0.158960i 0.449018-0.149611i 0.110072-0.104079i 0.290913-0.0960668i 0.1 0.169109-0.157354i 0.448207-0.148787i 0.108803-0.101841i 0.287647-0.0937670i 0.14 0.168720-0.155810i 0.447165-0.147679i 0.106439-0.098191i 0.283246-0.0906137i 0.18 0.168023-0.153998i 0.443449-0.145653i 0.103804-0.0933381i 0.278075-0.0869171i 0.22 0.166891-0.151193i 0.441312-0.143235i 0.101889-0.0875931i 0.272255-0.0830565i 0.26 0.166014-0.148333i 0.437092-0.140916i 0.100331-0.0820946i 0.266262-0.0790222i 0.30 0.165430-0.144852i 0.432538-0.137778i 0.098978-0.0771625i 0.259892-0.0749341i 0.33 0.164395-0.143688i 0.429952-0.135908i 0.098060-0.0736714i 0.254996-0.0719146i Table 2. QNM frequencies of black holes within region of r0 > 0.876 in Group I.

r0=0.5

r0=0.7

Q ω(l=0)

ω(l=1)

ω(l=0)

ω(l=1)

0 0.1920-0.05801i 0.5650-0.1168i 0.2484-0.1550i 0.5574-0.4347i 0.02 0.191974-0.0578165i 0.563943-0.115416i 0.247626-0.15488i 0.556522-0.433647i 0.06 0.191900-0.0575649i 0.561869-0.114350i 0.245508-0.153018i 0.551806-0.407181i 0.1 0.191801-0.0572173i 0.556545-0.112453i 0.242262-0.150052i 0.550735-0.410594i 0.12 0.191707-0.0569421i 0.553771-0.111982i 0.240109-0.148196i 0.548074-0.403119i 0.155 0.191457-0.0563484i 0.547261-0.109390i 0.235633-0.144682i 0.542076-0.386617i 0.185 0.191279-0.0559977i 0.543921-0.104531i 0.231188-0.141623i 0.536208-0.369774i 0.215 0.190982-0.0555578i 0.534453-0.100874i 0.226304-0.138735i 0.530038-0.353073i 0.25 0.188420-0.0548792i 0.521852-0.094748i 0.220221-0.135954i 0.518341-0.344284i 0.29 0.185355-0.0536175i 0.508852-0.087635i 0.213025-0.133582i 0.508015-0.333045i Table 3. QNM frequencies of black holes within region of r0 < 0.876 in Group II.

r0=1

r0=1.1

Q ω(l=0)

ω(l=1)

ω(l=0)

ω(l=1)

0 0.2490-0.3900i 0.6920-0.2920i 0.2967-0.4970i 0.7764-0.3774i 0.02 0.248326-0.390859i 0.697313-0.292519i 0.298359-0.497294i 0.78196-0.3774330i 0.055 0.249730-0.398086i 0.699694-0.294816i 0.300096-0.497879i 0.786675-0.377930i 0.09 0.251139-0.403061i 0.706433-0.300164i 0.303839-0.507651i 0.795747-0.387478i 0.125 0.258110-0.418834i 0.713570-0.308565i 0.313144-0.495390i 0.795217-0.390079i 0.16 0.257806-0.426266i 0.722897-0.314524i 0.315173-0.529731i 0.816878-0.410238i 0.195 0.262761-0.434169i 0.731343-0.322654i 0.322461-0.538773i 0.827657-0.422568i 0.23 0.266851-0.445229i 0.740003-0.332937i 0.328884-0.559389i 0.842650-0.437051i 0.28 0.279679-0.465540i 0.749440-0.341363i 0.341379-0.571647i 0.860521-0.459423i Table 4. QNM frequencies of black holes within region of r0 > 0.876 in Group II.

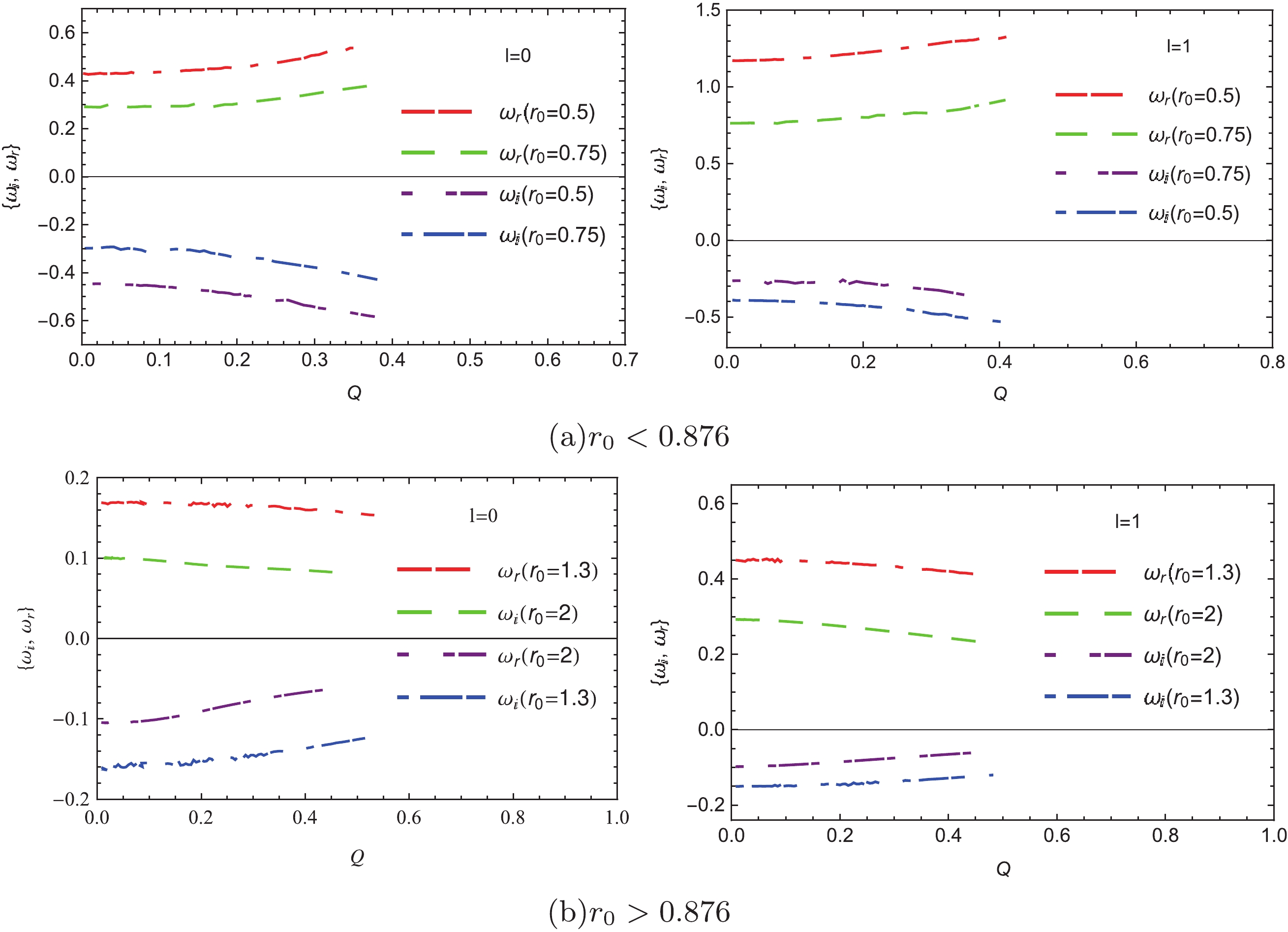

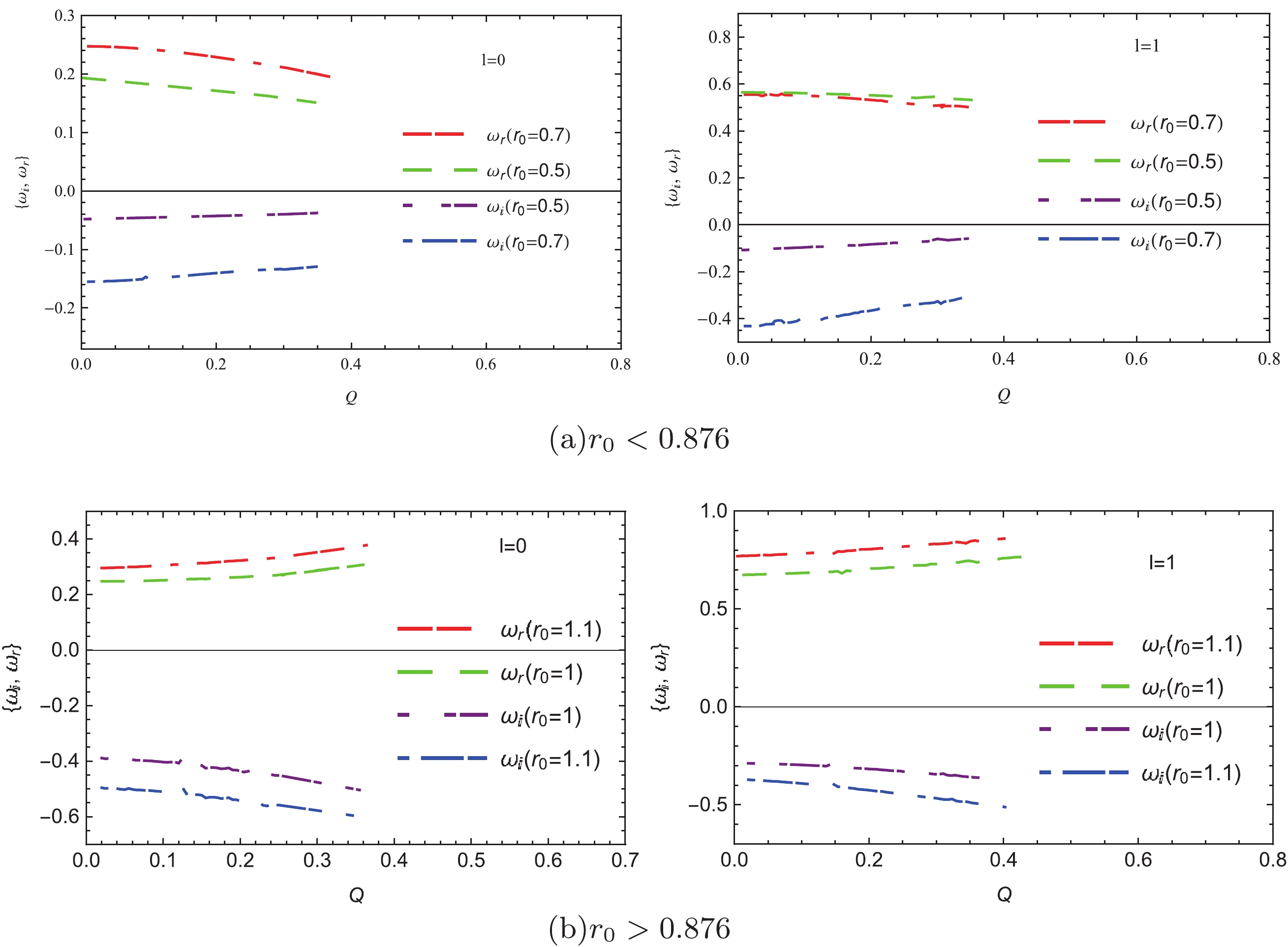

For charged black holes, the imaginary parts are always negative, indicating that these modes always decay and are therefore stable. Moreover, for the charged black holes with

r0=0.5 and 0.75 in Group I, the absolute values of the imaginary part(|ωi|) and real part(ωr) of QNM frequencies(l=0,1) both increase with increasing of Q (see Table 1 and Fig. 2(a)). In contrast, the corresponding values of|ωi| andωr of QNM frequencies for charged black holes withr0=1.3 and 2 in Group I both decrease with increasing of Q (see Table 2 and Fig. 2(b)). Similarly, QNM frequencies of these charged black holes in Group II, located each side of the coalescent pointT≈0.091(r0≈0.876) , exhibit different trends from the ones given in Tables 3, 4 and Fig. 3. This is because the mass M and temperature T of these charged black holes affect the boundary conditions of the test scalar fieldΨl(r) given in Eq. (10). However, based on the free energies (Fig. 7 in Ref. [13]) and QNM frequencies of these charged and neutral black holes [Figs. 2 and 3], the correlation between thermodynamic phase transitions and dynamical stabilities fails.

Figure 2. (color online) Dependence of fundamental QNM frequencies of charged black hole on charge Q with fixed horizon radius in Group I.

Figure 3. (color online) Dependence of fundamental QNM frequencies of charged black hole on charge Q with fixed horizon radius in Group II.

Notably, the study of Ref. [30] asserted that QNM frequencies

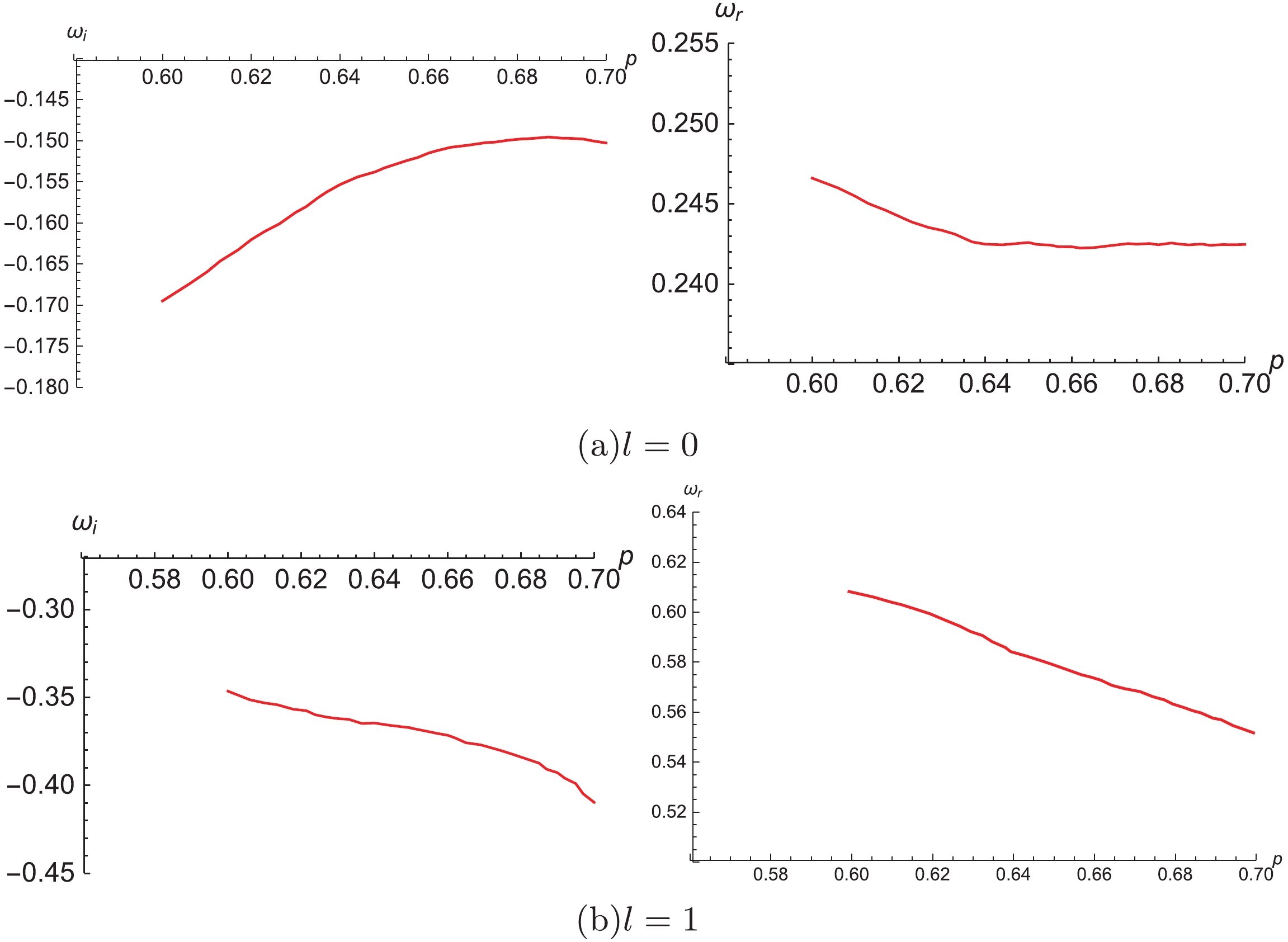

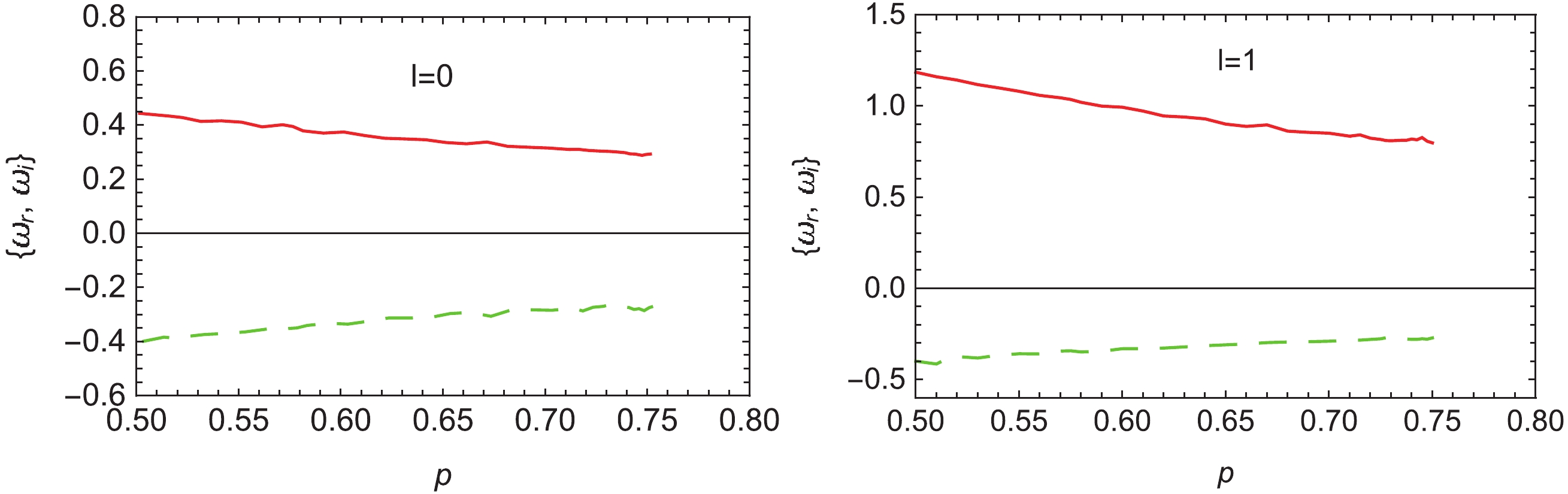

ω are linearly dependent onp=r0√2α for NSBH in the EW gravity. Following a similar path, we assumeα=1/2 and a fixed charge Q, and subsequently consider QNMs of the new charged black holes with a different horizon radiusr0 (here, we do not show new numerical solutions) for various multipole numbers l, assumingp=r0√2α=r0 . According to QNM frequencies of charged black holes withr0=p=0.5 in Group I andr0=p=0.7 in Group II, these new QNM frequencies are expressed as a function of p in Table 5 and Figs. 4 and 5. In comparison with QNMs of charged black holes withp=r0=0.5 , the new charged black holes with different values ofp=r0>0.5 exhibit lower real frequencies and a lower damping rate. Moreover, the tendency of the imaginary part of QNM frequencies forl=1 changes, as shown in Fig. 5(b). Finally, we do not observe the strict linear relation betweenω and p, as the charge Q causes a nonlinear effect on the frequency for these charged black holes in the EMW gravity.

Figure 4. (color online) Dependence of QNM frequencies of charged black hole on parameter p with

Q=0.1 starting fromQ=0.1 andp=r0=0.5 in Group I. Solid and dashed lines denote the real and imaginary parts of QNM frequencies, respectively.Group I Group II p ω(l=0)

ω(l=1)

p ω(l=0)

ω(l=1)

0.5 0.451303-0.428182i 1.185030-0.399112i 0.7 0.242462-0.150258i 0.551352-0.409716i 0.54 0.423578-0.399711i 1.099260-0.366381i 0.685 0.242485-0.150641i 0.560200-0.387280i 0.58 0.386467-0.369919i 1.019980-0.348577i 0.665 0.242862-0.151787i 0.568930-0.372865i 0.63 0.356692-0.342205i 0.939253-0.320923i 0.65 0.243282-0.153298i 0.574191-0.367385i 0.68 0.329482-0.312415i 0.862011-0.294039i 0.64 0.243481-0.155328i 0.583836-0.360624i 0.72 0.313943-0.302641i 0.823348-0.279923i 0.62 0.244227-0.162025i 0.601820-0.359452i 0.75 0.300831-0.297926i 0.797623-0.271460i 0.6 0.246600-0.169481i 0.60298-0.346543i Table 5. Dependence of QNM frequencies of charged black hole on parameter p with fixed

Q=0.1 in Groups I and II. -

We consider how the behavior of QNMs changes depending on the massive scalar field

μ≠0 . Under the massive scalar field perturbation, the boundary conditions are different from those in the massless case. From the radial perturbed Schrödinger Eq. (7), the respective ingoing boundary conditions at the black hole event horizon and outgoing boundary conditions at spatial infinity are obtained asΨl(r)∼{e−iωr∗∼(r−r0)−iω4πT,r→r0ei(μ2−ω2)1/2r∗∼rme−(μ2−ω2)1/2rr−2M(μ2−ω2)1/2r→∞

(11) We take as an example the charged black holes with

r0=0.5 andQ=0.1 in Group I. The QNM frequencies as a function of massμ are shown in Fig. 6 [38]. For the angular parameterl=0 , the real part of the QNM frequencies becomes larger, while the imaginary part decreases with increasing massμ . This indicates that massive modes are scattered more slowly than massless modes. Moreover, these oscillations could become undamped, i.e.,ωi=0 , under certain conditions, causing the appearance of so-called quasiresonances. This phenomenon emerged for the massive scalar field perturbation in the NSBH background in EW gravity [30] and the charged field perturbation in the RN black hole [39, 40, 41]. Nevertheless, these quasiresonances disappear forl=1 in the EMW gravity. -

Applying the Einstein-Maxwell-Weyl theory, we investigated QNMs and the stability of charged black holes under the test scalar field perturbation. With an increase in the charge Q, QNM frequencies are depicted by larger (smaller) real oscillations and higher (lower) damping rates, than those for the neutral branches at the same side of the coalescent point

T≈0.091(r0≈0.876) , in both Groups I and II. Moreover, these phenomena are reflected by the behaviors of the thermodynamic quantities M and T. Furthermore, the linear dependence of the QNM frequency on the parameter p for NSBH in the EW gravity does not manifest for the new charged black holes in the EMW gravity, as the charge Q causes a nonlinear effect on QNM frequencies. Furthermore, we discussed the case of a massive scalar field perturbation, where undamped oscillations occur for sufficiently large masses.Recently, (anti-) de Sitter charged black hole solutions in the EMW gravity were presented [11]. Because of the dual conformal field theory, QNM frequencies of AdS black holes have a direct interpretation [42, 43]. Therefore, it would be interesting to consider QNMs and the stability of charged AdS black holes in the EMW gravity.

Abstract

Abstract HTML

HTML Reference

Reference Related

Related PDF

PDF

DownLoad:

DownLoad: