-

The fission of atomic nuclei is considered among the most complex physical phenomena in nuclear physics. It involves a rapid re-arrangement of nuclear matter with a delicate interplay between the macroscopic bulk matter and microscopic quantal properties [1, 2]. Although the properties of fission have been studied exhaustively, numerous aspects of the dynamics are still not well understood. For instance, discrepancies have been reported between the measured fission observables and the predictions of the classical theory based on the standard Bohr–Wheeler statistical model of fission [3]. In particular, fission hindrance, enhanced pre-scission particles, and giant dipole resonance (GDR) γ-ray multiplicities observed in hot nuclei suggest the effects of nuclear dissipation, which slows down the fission process [4–10]. To account for frictional effects, the Kramers diffusion model formalism with a modified fission width [11], referred to as the Kramers-modified statistical model, has been included in the standard statistical theory.

Although the nature and strength of nuclear dissipation have been studied quite extensively, a simultaneous description of the experimental observables, namely pre-scission neutron multiplicities (

$\nu_{\rm pre}$ ), fission excitation functions, and evaporation residue (ER) cross-sections, still remains challenging. Additionally, the dissipation coefficient is often treated as an adjustable free parameter in the statistical model analysis. The pre-fission lifetime (or dissipation strength), level density parameter of the ground state, saddle point deformation, and fission barrier are empirically fitted to explain$\nu_{\rm pre}$ and/or the fission and ER cross-section data [6, 12–15]. Consequently, the conclusions derived are often system dependent and are inadequate in providing a consistent description of the fission process.Notably, such inadequate modeling of fission in statistical models can drastically influence the understanding of the fission phenomenon [16, 17]. This is particularly observed in the mass region of (A)

$ \approx $ 200, which is explored here to understand the role of the N$ = $ 126 neutron shell closure in a fissioning compound nucleus (CN). An anomalous increase in the experimental fission fragment angular anisotropy has been reported for$ ^{210} $ Po (N$ = $ 126) as compared with that for$ ^{206} $ Po (non-shell closed nuclei) across an excitation energy range of ($E_{\rm ex}) \approx$ 40$ - $ 60 MeV, and this has been conjectured to be a manifestation of shell effects at the unconditional saddle [18]. Further, a considerable amount of saddle shell correction has been invoked to describe the experimental$\nu_{\rm pre}$ data for the$ ^{210} $ Po nuclei [19]. However, a re-investigation of the experimental excitation functions and$\nu_{\rm pre}$ data for$ ^{210} $ Po ruled out any significant shell influence on the saddle [20] after correlated tuning of the statistical-model parameters and an inclusion of fission delay.Another interesting aspect is the contradictory interpretation of the correlation between the neutron shell structure and the nuclear dissipation strength required to reproduce the measured ER and

$\nu_{\rm pre}$ excitation functions of the N$ = $ 126 shell closed nuclei, namely$ ^{212} $ Rn and$ ^{213} $ Fr. A theoretical analysis of the$\nu_{\rm pre}$ data for$ ^{212} $ Rn [21] and$ ^{213} $ Fr [22] reported a low dissipation strength at$E_{\rm ex}\approx$ 50 MeV, which was attributed to the influence of neutron shell closure. On the contrary, no discernible shell influence was reported by ER cross-section studies of$ ^{212} $ Rn and its isotope [23], although moderate nuclear dissipation was required to describe the data. Notably, the magnitude of the dissipation invoked to explain the experimental ER cross-sections varied across Rn isotopes [23, 24], which is again found to be differentfor a description of the $\nu_{\rm pre}$ data [21]. Interestingly, for Fr nuclei, the finite-range liquid drop model fission barrier was scaled down, particularly for$ ^{213} $ Fr, to fit the measured ER cross-section [15]. This reduction in the fission barrier disagreed with the predictions for a shell closed nucleus [25]. One notable observation is the reported interpretation of the reduced survival probability of the$ ^{213} $ Fr nucleus owing to the neutron shell, which is in contrast to the isotopic trend reported for Rn isotopes. Further, the fission cross-section for$ ^{213} $ Fr is reported to experience no extra stability owing to the N=126 shell closure [26]. Notably, in the statistical model approach adopted in these studies, no attempts were made to extract a global prescription of the parameters; instead, a case specific adjustment of the dissipation strength was involved. The influence of neutron shell structures on the potential energy surface and, hence, fission observables still remains quite ambiguous. Apart from the shell influence, entrance channel effects have also been probed in a couple of recent publications to understand the experimental$\nu_{\rm pre}$ data for$ ^{213} $ Fr nuclei [27, 28]. These studies reportedly observed a deviation in the measured data with respect to the predictions of the entrance channel model for$ ^{16} $ O- and$ ^{19} $ F-induced reactions.The foregoing studies substantiate that no consistent picture has yet emerged from the recent independent analyses of each fission observable for the following neutron shell closed nuclei

$ ^{210} $ Po,$ ^{212} $ Rn, and$ ^{213} $ Fr and their isotopes. Further, inadequacies related to the standard statistical model interpretations have been addressed by employing the Kramers-modified fission width and considering the shape-dependent level density, temperature-dependent fission transition points, orientation (K state) degree of freedom, and temperature-independent reduced dissipation coefficient [16, 17]. Moreover, attempts for restraining the statistical-model parameters have also been reported [29]; however, a consistent description of the experimental data for all three observables, namely$\nu_{\rm pre}$ , fission, and ER excitation functions for shell closed nuclei, is yet to be achieved. In this direction, recent developments in multi-dimensional stochastic approaches have been fairly successful in describing the fission characteristics of excited nuclei [30–35]. However, a simultaneous description of the experimental data and a systematic study of shell closed nuclei are yet to be attempted.In this study, we demonstrate that a dynamical model based on the 1D Langevin equation coupled with a statistical approach [36] can simultaneously reproduce

$\nu_{\rm pre}$ , fission, and the ER cross-section data of shell closed nuclei over the excitation energy range ($E_{\rm ex} \approx$ 40$ - $ 80 MeV) of the measurements. Note that the present calculations were performed without adjusting any of the model parameters, thus providing a unified framework for a simultaneous study of these fission observables for nuclei in the A$ \approx $ 200 region. We re-investigated the available experimental data for the following neutron shell closed nuclei$ ^{210} $ Po,$ ^{212} $ Rn, and$ ^{213} $ Fr and their non-shell closed isotopes$ ^{206} $ Po,$ ^{214,216} $ Rn, and$ ^{215,217} $ Fr. Consequently, we observed that a universal deformation-dependent reduced friction parameter was capable of describing the fission observables simultaneously at all measured energies irrespective of the shell structures of the nuclei. -

A combined dynamical and statistical model code [37] is utilized to compute the fission observables of the nuclei under study. A detailed description of the theoretical aspects of the model can be found elsewhere [36, 38]. The dynamical part of the model is analyzed with a 1D Langevin equation of motion governed by a driving potential that is determined by the free energy F(q, T), as in recent studies [39–44]. The free energy, as derived from the Fermi gas model, is related to the deformation dependent level density parameter a(q, A) as F(q, T) = V(q) - a(q, A)

$ T^2 $ , where T is the nuclear temperature; q is a dimensionless deformation coordinate, which is defined as the ratio of half the distance between the center of masses of future fission fragments to the radius of the CN; and$ V(q) $ is the nuclear potential energy obtained from the finite-range liquid drop model [45, 46]. Previously, Fröbrich [47] and Lestone$ et $ $ al $ . [17] emphasized using the nuclear entropy given by S(q, A,$E_{\rm tot}$ ) =$2 \sqrt{a(q, A)[E_{\rm tot}-V(q)]}$ for determining the driving force, and therefore, it is employed as a crucial quantity in the model. The nuclear driving force K = –$\dfrac{{\rm d}V(q)}{{\rm d}q}$ +$\dfrac{{\rm d}a(q)}{{\rm d}q}T^{2}$ not only consists of a conservative force but also contains a thermodynamical correction that enters the dynamics via the level density parameter a(q, A). The deformation dependent level density parameter used in constructing the entropy has the following form [48]:$ \begin{equation} a(q,A) = \tilde{a_1}A + \tilde{a_2}A^{2/3}B_s(q), \end{equation} $

(1) where A is the mass number of the CN, and

$ \tilde{a_1} $ = 0.073 MeV$ ^{-1} $ and$ \tilde{a_2} $ = 0.095 MeV$ ^{-1} $ are obtained from Ref. [49]. B$_{s}$ (q) is the dimensionless functional of the surface energy [34, 38, 43, 50], which is expressed as a ratio of the surface energy of the composite system to that of a sphere.The over-damped Langevin equation, which describes the fission process in the dynamical part of the model, has the following form [36]:

$ \begin{equation} \frac{{\rm d}q}{{\rm d}t} = \frac{T}{M\beta(q)} \left[\frac{\partial S(q)}{\partial q} \right]_ {{E}_{\rm tot}}+ \sqrt{\frac{T}{M\beta(q)}} \Gamma(t), \end{equation} $

(2) where

${E}_{\rm tot}$ is the total energy of the composite system that remains conserved, and$ \Gamma(t) $ is a Markovian stochastic variable with a normal distribution. The reduced dissipation coefficient$ \beta(q) $ = γ/M (as employed in the literature; see e.g., Refs. [16, 29, 42, 44] (and Refs. therein)) is the ratio of the friction coefficient γ to the inertia parameter M calculated based on the Werner−Wheeler approximation for an incompressible irrotational fluid [51]. The present model employs "funny$ - $ hills" parameters$\{c,h, \alpha\} $ [52] for describing the shape of the fissioning nuclei. Further, considering only symmetric fission, the mass asymmetry parameter of the shape evolution is set to α=0 [36, 38, 50]. The dimensionless fission coordinate (q) is given by q(c, h)= ($ \dfrac{3c}{8} $ )(1+$ \dfrac{2}{15} $ [2h+$ \dfrac{(c-1)}{2} $ ]c$ ^{3} $ ), where c and h define the elongation and neck degree of freedom of the fissioning nucleus, respectively [36, 43, 53, 54].Notably, following the fission dynamics through the full Langevin dynamical calculation is quite time consuming. Similar to previous Langevin studies [31, 36, 39–43], a computationally less intensive approach is adopted in the present study, and herein, the dynamical stage is coupled with a statistical model. In the present calculations, the emission of light particles from the ground state to the scission configuration along the Langevin trajectories is treated as a discrete process. The evaporation of pre-scission light particles from the ground state of the Langevin trajectories to the scission point is coupled with the fission mode via a Monte Carlo procedure. The decay width

for light particle evaporation at each Langevin time step is calculated based on the formalism suggested by Fröbrich $ et $ $ al $ . [36] and later incorporated in Refs. [34, 40–43]. The emission width of a particle of type ν (n, p, α) is given as follows [55]:$ \begin{aligned}[b] \Gamma_{\nu} =& (2s_{\nu}+1) \frac{m_{\nu}}{\pi^{2}\hbar^{2}\rho_{c}(E_{\rm ex})} \\&\times \int_{0}^{(E_{\rm ex}-B_{\nu})} {\rm d}\epsilon_{\nu}\rho_{R}(E_{\rm ex}-B_{\nu}-\epsilon_{\nu})\epsilon_{\nu}\sigma_{\rm inv}(\epsilon_{\nu}), \end{aligned} $

(3) where

$ s_{\nu} $ is the spin of the emitted particle ν, and$ m_{\nu} $ is its reduced mass with respect to the residual nucleus. The level densities of the compound and residual nuclei are denoted by$ \rho_{c} $ (E$_{\rm ex}$ ) and$ \rho_{R} $ (E$_{\rm ex}-B_{\nu}-\epsilon_{\nu}$ ), respectively. B$ _{\nu} $ is the liquid-drop binding energy,$ \epsilon $ is the kinetic energy of the emitted particle, and$\sigma_{\rm inv}(\epsilon_{\nu}$ ) is the inverse cross-section [55]. The decay width for light particle emission is calculated at each Langevin time step τ [43, 53, 54].When a stationary flux is reached over the barrier after a sufficiently long delay time, the decay of the CN can then be modelled by an adequately modified statistical model [38, 56, 57]. To ensure continuity when switching from the dynamical to the statistical branch, an entropy dependent fission width is incorporated into the latter. While entering the statistical branch, the particle emission width

$ \Gamma_{\nu} $ is re-calculated, and the fission width$ \Gamma_{f} $ =$ \hbar $ R$ _{f} $ [36] is obtained based on the fission rate (R$ _{f} $ ) given as follows:$ \begin{aligned}[b] R_{f} =& \frac{T_{gs}\sqrt{|S^{''}_{gs}|S^{''}_{sd}}} {2\pi M \beta_{gs}}{\rm exp}[S(q_{gs})-S(q_{sd})]\\& \times 2(1+ {\rm erf} [(q_{sc}-q_{sd})\sqrt{S^{''}_{sd}/2}])^{-1}. \end{aligned} $

(4) Here, erf(x) = (2/

$ \sqrt{\pi} $ )$ \int_{0}^{x} $ dt exp($ -t^{2} $ ) is the error function, and$ \beta_{gs} $ is the ground state dissipation coefficient. The saddle-point (q$ _{sd} $ ) and the ground-state positions (q$ _{gs} $ ) are defined by the entropy and not by the potential energy as in the conventional approach. The standard Monte Carlo cascade procedure is used to select the type of decay with weights$ \Gamma_{i} $ /$\Gamma_{\rm tot}$ (i = fission, n, p, d, α) and$\Gamma_{\rm tot}$ =$ \sum_{i}\Gamma_{i} $ . Pre-scission particle multiplicities are calculated by counting the number of corresponding evaporated particle events registered in the dynamical and statistical branches of the model.The Langevin equation is initiated from a ground state configuration with a temperature corresponding to the initial excitation energy. The fusion cross-section can be determined based on the partial cross-section

$\dfrac{{\rm d}\sigma(l)}{{\rm d}l}$ , which represents the contribution of the angular momenta l to the total fusion cross-section. Each Langevin trajectory is initiated with an orbital angular momentum, which is sampled from a fusion spin distribution that reads as follows [34, 36]:$ \frac{{\rm d}\sigma(l)}{{\rm d}l} = \frac{2\pi}{k^{2}}\frac{2l+1}{1+\exp{\dfrac{(l-l_{c})}{\delta l}}} . $

(5) The final results are weighted over all relevant waves, that is, the spin distribution is used as an angular momentum weight function, based on which the Langevin calculations for fission are initiated. As presented in recent Langevin studies, [34, 39–44], the spin distribution is determined based on the surface friction model [58]. This calculation also fixes the fusion cross-section, thus guaranteeing a correct normalization of the fission and evaporation residue cross-sections within the accuracy of the surface friction model. The parameters

$ l_{c} $ and$ \delta l $ denote the critical angular momenta for fusion and diffuseness, respectively.The fission observables that will be discussed in the subsequent sections are obtained in the model as follows. The pre-scission neutron multiplicity is the number of neutrons emitted by the CN until it approaches the scission configuration. The fission probability (

$ P_{f} $ ) is given by the ratio of the fissioned trajectories to the total trajectories. The CN survival probability (1-$ P_{f} $ ) is given by the number of trajectories leading to ER formation divided by the number of total trajectories, and the fission (ER) cross-section is given by the product of the fission (survival) probability and the fusion cross-section. -

In the present study, pre-scission neutron multiplicities and fission and ER excitation functions are computed for

$ ^{206,210} $ Po,$ ^{212,214,216} $ Rn, and$ ^{213,215,217} $ Fr compound nuclei and are compared with available experimental data, where$ ^{210} $ Po,$ ^{212} $ Rn, and$ ^{213} $ Fr are N=126 neutron shell closed nuclei.Table 1 lists the important parameters for the reactions considered in this study. The dynamical calculations are performed based on a universal frictional form, as in Refs. [36, 47, 57],with a consistent prescription of the dissipation coefficient without adjusting any of the model parameters. To ensure good statistics, $ 10^7 $ Langevin trajectories are considered in the model calculations.CN fissility $ S_{n} $ /MeV

$ B_{f} $ (l=0)/MeV

Reaction Mass excess/MeV α/ $\alpha_{\rm BG}$

target(proj) CN $ ^{206} $ Po

0.717 7.99 10.51 $ ^{12} $ C+

$ ^{194} $ Pt

−34.79(0) −18.83 1.043 $ ^{210} $ Po

0.711 7.38 11.22 $ ^{12} $ C+

$ ^{198} $ Pt

−29.93(0) −16.33 1.050 $ ^{18} $ O+

$ ^{192} $ Os

−35.89(−0.78) −16.33 0.982 $ ^{212} $ Rn

0.732 7.83 8.88 $ ^{18} $ O+

$ ^{194} $ Pt

−34.79(−0.78) −9.26 0.970 $ ^{214} $ Rn

0.729 7.54 9.19 $ ^{16} $ O+

$ ^{198} $ Pt

−29.93(−4.74) −4.77 0.996 $ ^{216} $ Rn

0.727 7.25 9.49 $ ^{18} $ O+

$ ^{198} $ Pt

−29.93(−0.78) 0.70 0.977 $ ^{213} $ Fr

0.743 8.06 7.83 $ ^{16} $ O+

$ ^{197} $ Au

−31.16(−4.74) −4.01 0.987 $ ^{19} $ F+

$ ^{194} $ Pt

−34.79(−1.49) −4.01 0.954 $ ^{215} $ Fr

0.740 7.76 8.13 $ ^{19} $ F+

$ ^{196} $ Pt

−32.67 (−1.49) −0.07 0.958 $ ^{217} $ Fr

0.737 7.47 8.42 $ ^{19} $ F+

$ ^{198} $ Pt

−29.93(−1.49) 5.00 0.961 Table 1. Important parameters of the reactions studied.

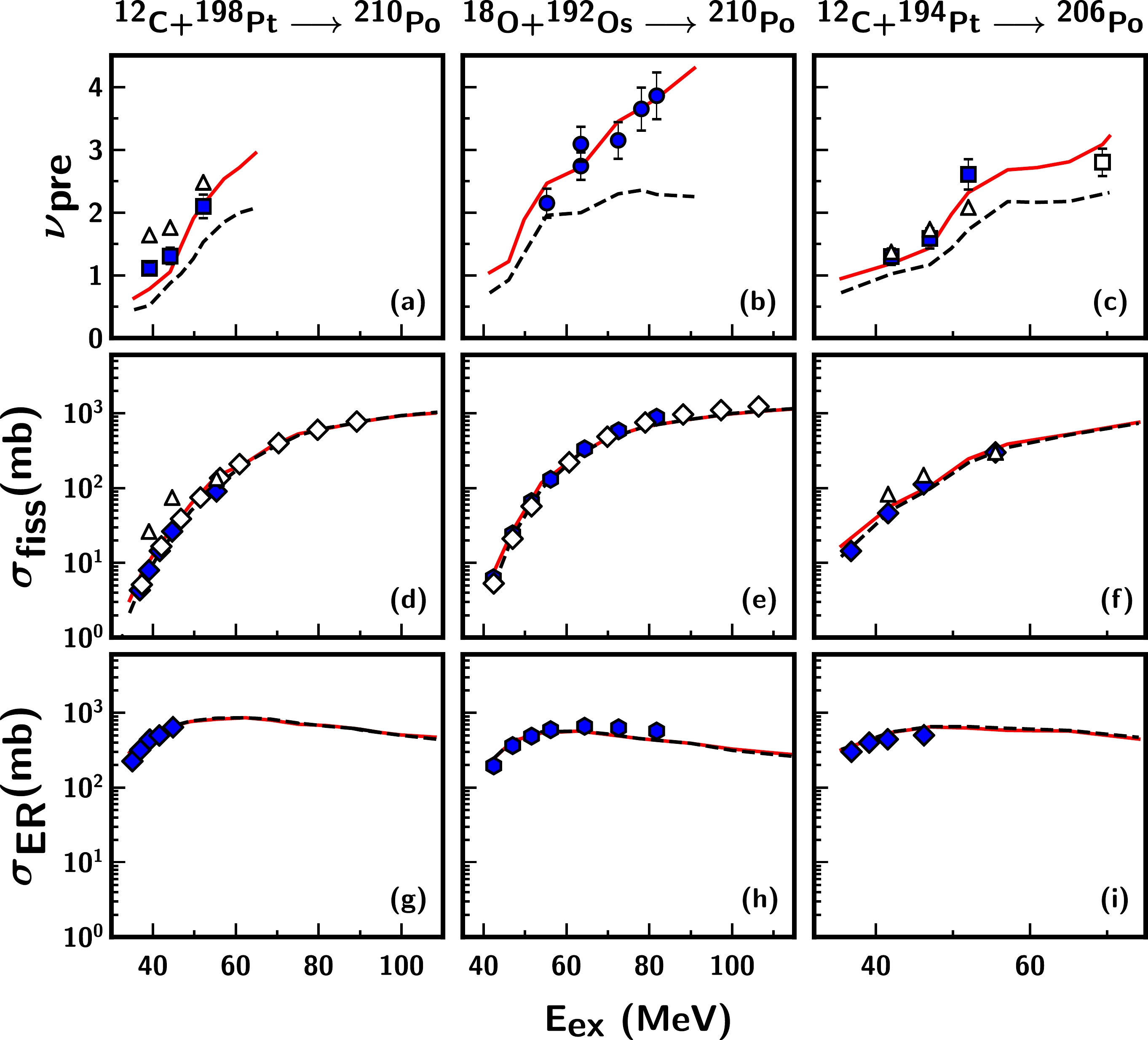

Figure 1 presents the results of the dynamical calculations compared with the experimental data for

$\nu_{\rm pre}$ and the fission and ER cross-sections of$ ^{206} $ Po formed via the$ ^{12} $ C+$ ^{194} $ Pt [18, 19, 59] reaction and$ ^{210} $ Po formed through two different entrance channel reactions, namely$ ^{12} $ C+$ ^{198} $ Pt [18, 19, 61] and$ ^{18} $ O+$ ^{192} $ Os [5, 60, 61], spanning a wide range of excitation energies. The excitation energies presented here are with respect to the liquid drop ground state CN mass and the experimental masses of the projectile and target [62]. Our calculations are restricted to excitation energies at and above 40 MeV, for which the present macroscopic model is valid. We emphasize that microscopic shell corrections are not accounted for in the present calculations, as we are dealing with hot nuclei, for which shell effects are expected to be negligible at high excitation levels that are populated in heavy-ion reactions. The results of the calculations obtained using only the statistical model (dashed line) are also shown in Fig. 1. These calculations are performed based on the same code without Langevin dynamics. The statistical model calculations under-predict the measured$\nu _{\rm pre}$ data, as shown in panels (a) to (c), and this effect increases as the excitation energy increases. The dynamical model calculations based on the universal reduced friction coefficient are in excellent agreement with the measured data of$\nu _{\rm pre}$ (panels (a) to (c)), fission cross-sections$\sigma_{\rm fiss}$ (panels (d) to (f)), and ER cross-sections$\sigma_{\rm ER}$ (panels (g) to (i)) for the neutron shell closed nucleus$ ^{210} $ Po, as well as its isotope$ ^{206} $ Po. The measured data for$ ^{210} $ Po formed through two different entrance channels agree well with the theory for a broad range of excitation energies up to 80 MeV. The model calculations also describe the available experimental data for$ ^{206,210} $ Po at these excitation energies without any microscopic corrections included in the model. These observations disagree with the statistical model analyses of the$ ^{12} $ C+$ ^{194} $ Pt and$ ^{12} $ C+$ ^{198} $ Pt reactions, which have previously reported a significant shell correction at the saddle deformation to describe the angular anisotropy and$\nu _{\rm pre}$ data [18, 19]. A recent 4D Langevin dynamical study [63] that was carried out on$ ^{206} $ Po and$ ^{210} $ Po that were generated from the reaction$ ^{12} $ C+$ ^{198} $ Pt provided a reasonable description of the measured data for these reactions without invoking any extra shell corrections at the saddle state; these are shown as open triangles in panels (a), (c), (d), and (f) of Fig. 1. A better agreement between the measured data is observed for the$ ^{12} $ C+$ ^{198} $ Pt reaction in comparison to its 4D Langevin calculations [63], particularly at low excitation energies, as shown in panels (a) and (d) of Fig. 1. The overestimation of$\nu _{\rm pre}$ and the fission cross-section of$ ^{210} $ Po reported in Ref. [63] can be attributed to the remnants of the ground state shells, and this is hence a consequence of not using a pure macroscopic potential energy surface as suggested in Ref. [64]. Nonetheless, the predictions of the multi-dimensional Langevin model for the$\nu _{\rm pre}$ data of$ ^{206} $ Po as suggested by Karpov$ et $ $ al $ . [30] are also found to be in reasonable agreement with the results of the present analysis. Moreover, the obtained mass distribution of the fragments in the fission of$ ^{206,210} $ Po [65, 66] reaffirms the absence of any shell corrections for the potential energy surface at the saddle point.

Figure 1. (color online) Measured and calculated pre-scission neutron multiplicities (

${\nu_{\rm pre}}$ ), fission cross-sections (${\sigma_{\rm fiss}}$ ), and ER cross-sections (${\sigma_{\rm ER}}$ ) as functions of the excitation energy for the following reactions:$ ^{12} $ C$ +^{198} $ Pt,$ ^{18} $ O$ +^{192} $ Os, and$ ^{12} $ C$ +^{194} $ Pt. The continuous line (red) denotes the obtained results with a universal frictional form factor, and the dashed line (black) represents the statistical model calculations. The symbols in the legend represent different experimental datasets. For${\nu_{\rm pre}}$ , (filled squares) Ref. [19], (filled circles) Ref. [5], and (open square) Ref. [59]; for${\sigma_{\rm fission}}$ and${\sigma_{\rm ER}}$ , (filled diamonds) Ref. [18], (filled hexagons) Ref. [60], and (open diamonds) Ref. [61]. The open triangles represent results of${\nu_{\rm pre}}$ and${\sigma_{\rm fission}}$ from the 4D Langevin calculations reported in Ref. [63].Figures 2 and 3 display a comparison between the experimental data and theoretical calculation results of

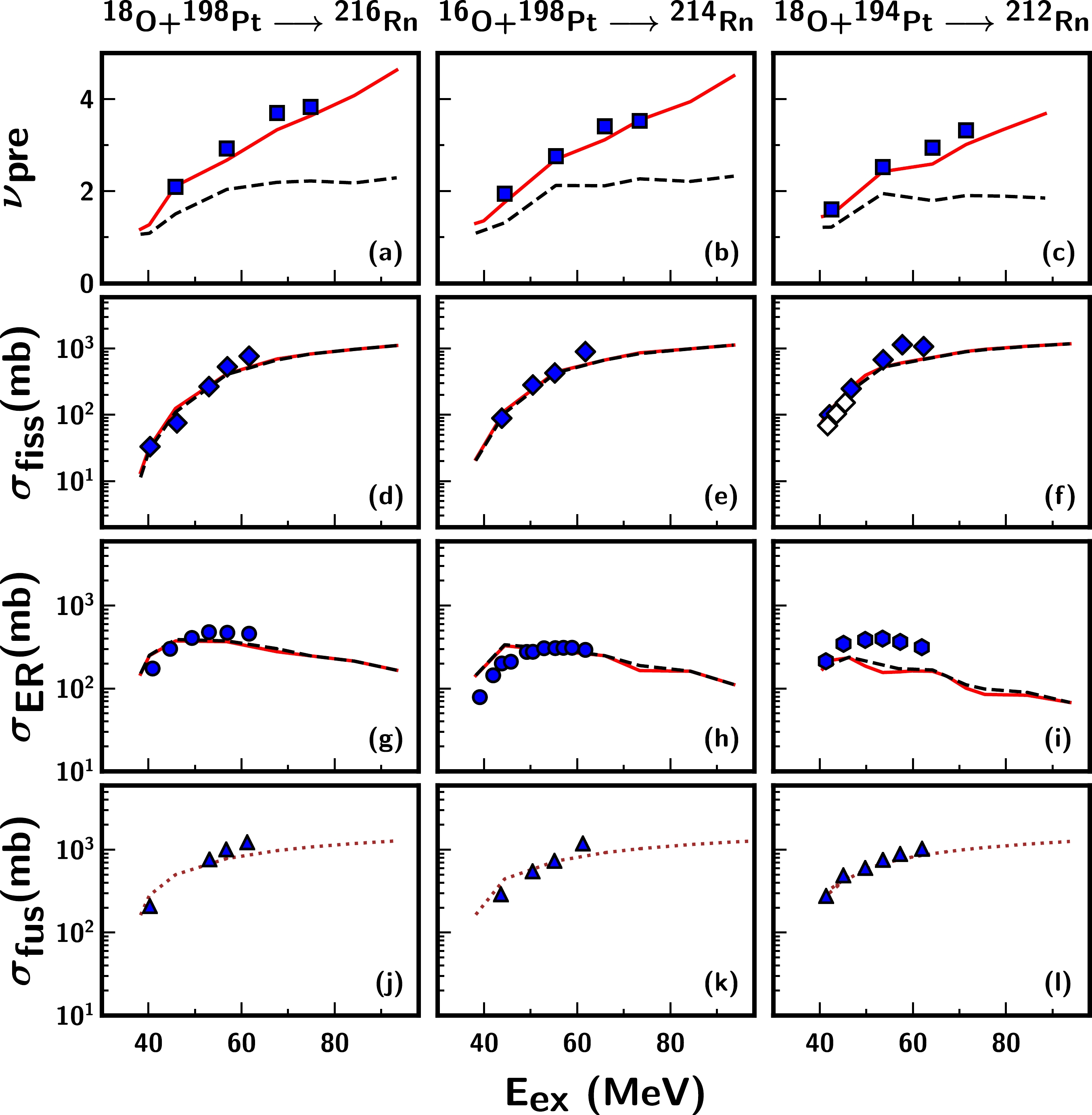

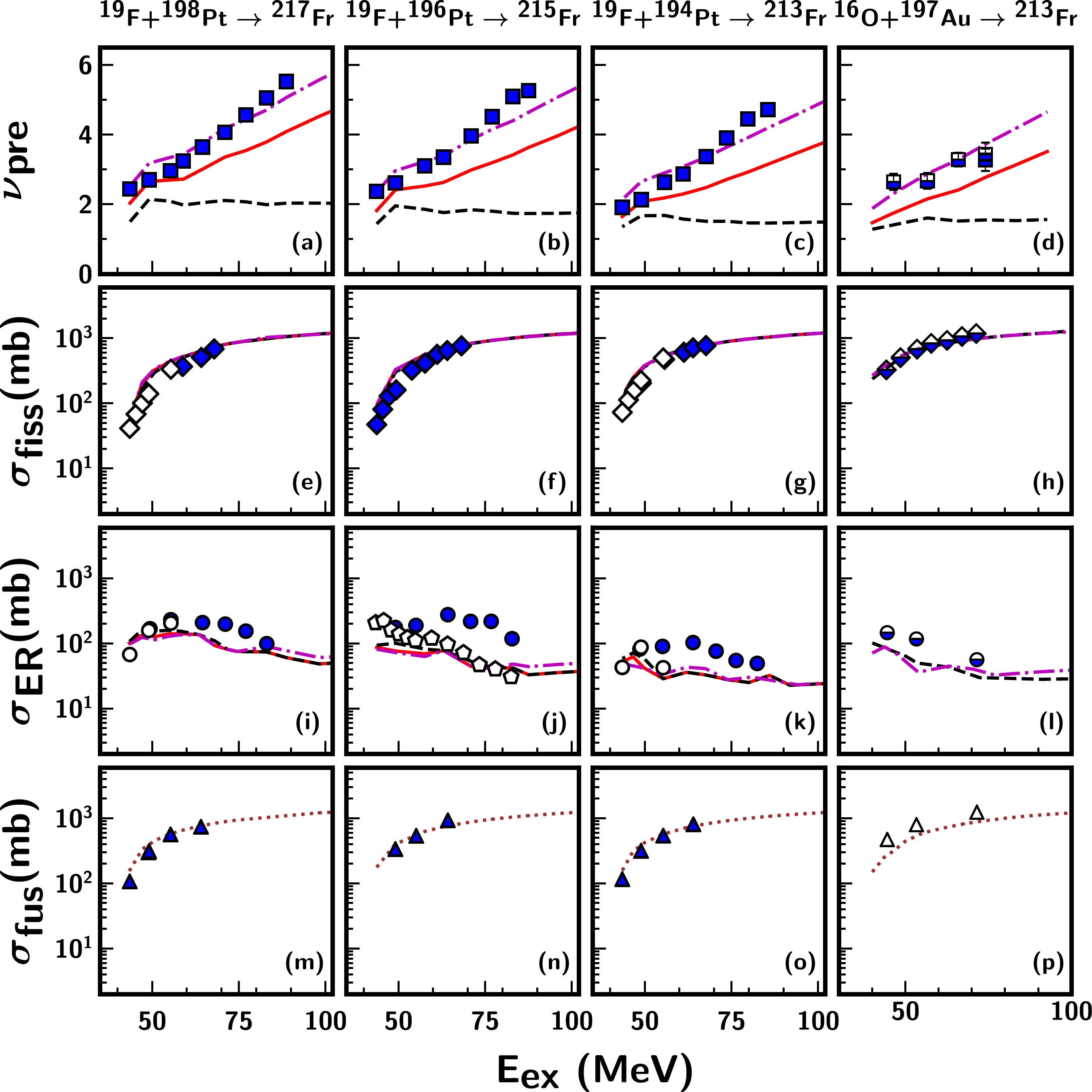

$\nu_{\rm pre}$ , the fission, ER, and fusion cross-sections for N$ = $ 126 shell closed nuclei including$ ^{212} $ Rn [21, 23, 24, 67] formed through the reaction$ ^{18} $ O+$ ^{194} $ Pt,$ ^{213} $ Fr formed through reactions$ ^{19} $ F+$ ^{194} $ Pt [15, 22, 26, 68] and$ ^{16} $ O+$ ^{197} $ Au [5, 6], and their non-shell closed isotopes$ ^{214,216} $ Rn generated via the reaction$ ^{16,18} $ O+$ ^{198} $ Pt [21, 23, 24, 67] and$ ^{215,217} $ Fr generated via the reaction$ ^{19} $ F+$ ^{196,198} $ Pt [15, 22, 26, 68]. As indicated, the model calculations describe the$\nu_{\rm pre}$ and fission excitation functions for$ ^{212} $ Rn and its isotopes$ ^{214,216} $ Rn quite successfully. In the reactions generating$ ^{213,215,217} $ Fr nuclei, the same parameter set is able to account for the experimental fission excitation functions but not for$\nu_{\rm pre}$ . A recent study [26] using an extended version of the statistical model employing collective enhancement of the level density also reported an under-estimation of the$\nu_{\rm pre}$ data for the same reactions when fitted simultaneously with the fission cross-section. In the present study, the disagreement between the experimental$\nu_{\rm pre}$ and theoretical values is prominent above an excitation energy of$ \approx $ 50 MeV, and this increases with an increase in the excitation energy. Considering that the$\nu_{\rm pre}$ values of other studied nuclei are well reproduced by the model, the failure of the same frictional form, particularly for reactions forming Fr nuclei, remains unclear. It is to be noted that an energy dependent dissipation was used in Refs. [21, 22] to describe the$\nu_{\rm pre}$ data for these reactions. We also adopted a similar approach by employing temperature-dependent friction (TDF) in the stochastic calculations [69] (without changing any other parameters). This frictional form factor is deformation dependent, unlike the ones used in Refs. [21, 22, 70]. The maximum of$ \beta(q) $ in the TDF corresponds to the ground state, which tends to decrease with increasing deformation, and its minimum lies near the saddle configuration; this is followed by an increase in the dissipation strength when approaching the scission. The dissipation coefficient assumes a higher value with increasing temperature of the CN. It is observed that a better agreement with the$\nu_{\rm pre}$ data can be achieved for the following reactions$ ^{19} $ F+$ ^{194,196,198} $ Pt and$ ^{16} $ O+$ ^{197} $ Au after invoking the temperature dependence of the dissipation. The same frictional form, however, is found to over-predict the measured$\nu_{\rm pre}$ data for the other nuclei under investigation and hence is not shown here.

Figure 2. (color online) Measured and calculated pre-scission neutron multiplicities (

${\nu_{\rm pre}}$ ), fission cross-sections (${\sigma_{\rm fiss} }$ ), ER cross-sections (${\sigma_{\rm ER} }$ ), and fusion cross-sections (${\sigma_{\rm fus} }$ ) as functions of the excitation energy for the following reactions:$ ^{18} $ O$ +^{198} $ Pt,$ ^{16} $ O$ +^{198} $ Pt, and$ ^{18} $ O$ +^{194} $ Pt. The continuous (red) and dashed (black) lines have the same meaning as in Fig. 1. The calculations of the fusion cross-section are independent of the frictional form and are represented by a dotted line (brown). The symbols in the legend represent different experimental datasets. For${\nu_{\rm pre}}$ , (filled squares) Ref. [21]; for${\sigma_{\rm fiss} }$ , (filled diamonds) Ref. [67] and (open diamonds) Ref. [23]; for${\sigma_{\rm ER}}$ , (filled circles) Ref. [24] and (filled hexagons) Ref. [23]; and for${\sigma_{\rm fus}}$ , (filled triangles) Refs. [23, 24].

Figure 3. (color online) Measured and calculated pre-scission neutron multiplicities (

$\nu_{\rm pre}$ ), fission cross-sections ($\sigma_{\rm fiss}$ ), ER cross-sections (${\sigma_{\rm ER} }$ ), and fusion cross-sections ($\sigma_{\rm fus}$ ) as functions of the excitation energy for the following reactions:$ ^{19} $ F$ +^{198} $ Pt,$ ^{19} $ F$ +^{196} $ Pt, and$ ^{19} $ F$ +^{194} $ Pt. The continuous (red), dashed (black), and dotted (brown) lines have the same meaning as in Figs. 1 and 2. The dash-dotted line (magenta) represents the results obtained with temperature-dependent friction. The symbols in the legend represent different experimental datasets. For${\nu_{\rm pre} }$ , (filled squares) Ref. [22] and (partially filled squares) Ref. [5]; for${\sigma_{\rm fiss} }$ , (filled diamonds) Ref. [26], (partially filled diamonds) Ref. [6], and (open diamonds) Ref. [68]; for${\sigma_{\rm ER} }$ , (filled circles) Ref. [15], (partially filled circles) Ref. [6], and (open circles) Ref. [68]; and for$\sigma_{\rm fus}$ , (filled triangles) Refs. [15, 26, 68] and (open triangles) Ref. [6]. The open pentagons denote${\sigma_{\rm ER}}$ for$ ^{215} $ Fr nuclei formed via$ ^{18} $ O$ +^{197} $ Au Ref. [71].Notably, deviations in the ER excitation functions are also observed for the

$ ^{212} $ Rn and$ ^{213,215,217} $ Fr nuclei, whereby the calculated ER cross-sections under-predict the experimental data for these nuclei at high excitation energies. Here, the case of the Rn isotopes is of particular interest as the ER cross-section data for$ ^{214,216} $ Rn [24] agree fairly well with the model calculations at all measured energies but differ for$ ^{212} $ Rn [23], except at the lowest energy. For the$ ^{213,215,217} $ Fr nuclei, the measured ER cross-sections reported in Ref. [15] differ above an excitation energy of$ \approx $ 55 MeV, and the deviation is prominent for$ ^{213,215} $ Fr. It is quite interesting to note that the ER measurement performed by a different group [68] for the same reactions generating$ ^{213,217} $ Fr at E$_{\rm ex}$ $ \leq $ 55 MeV follows the trend of the model predictions quite successfully. Unfortunately, the authors of Ref. [68] reported only three data points. Moreover, the ER cross-section data of$ ^{215} $ Fr formed in the reaction$ ^{18} $ O+$ ^{197} $ Au [71] agree reasonably well with the results of$ ^{19} $ F+$ ^{196} $ Pt, particularly above an excitation energy of 50 MeV (displayed as open pentagons in panel (j) of Fig. 3). The present dynamical calculations assume a decay from an equilibrated CN, without including any entrance channel effects. The model considers only different angular momenta that are populated in different entrance channels. Further, considering the insignificant difference in angular momenta between the two entrance channels forming$ ^{215} $ Fr, the observed deviation in the ER cross-section for the$ ^{19} $ F-induced reaction is quite unexpected. These observations further necessitate investigations on the deviations observed in ER cross-sections by comparing the measured fusion cross-sections for Rn and Fr nuclei with the model results. Consequently, the calculated fusion cross-sections are found to be in good agreement with the measured fusion data, augmenting the validity of the present calculations. Furthermore, the under-prediction of the ER cross-sections indicates the need for a strong dissipation in the pre-saddle region [72]. However, 3D Langevin dynamical calculations [31] have reported a reduction in the wall friction coefficient to reproduce the mass and kinetic energy distribution of the fission fragments and their influence on$\nu_{\rm pre}$ for the$ ^{215} $ Fr nucleus. The strength of the reduction coefficient k$ _s $ $ = $ 0.25$ - $ 0.5 indicates a weak dissipation in the initial stages of fissioning. An experimental analysis of the fission fragment nuclear-charge distributions and fission cross-sections of Fr and Rn isotopes and their neighbouring nuclei also reported a pre-saddle dissipation strength with a magnitude of (4.5$ \pm $ 0.5)$ \times $ 10$ ^{21} $ s$ ^{-1} $ [73] and 2$ \times $ 10$ ^{21} $ s$ ^{-1} $ [74], respectively. A more recent microscopic study on energy dependent dissipation based on the time-dependent Hartree-Fock + BCS method [75] also reportedthat the strength of the deformation dependent friction coefficient ranged from 1 to 6 $ \times $ 10$ ^{21} $ s$ ^{-1} $ for heavy nuclei. Notably, the strengths of these frictional parameterizations are in agreement with the dissipation form factor employed in the present calculations. These observations affirm a weak dissipation in the pre-saddle region; hence, the observed enhancement in the ER cross-sections of Fr nuclei generated via$ ^{19} $ F-induced reactions is not well understood from the perspective of the dissipation strength alone. In fact, a satisfactory description of the excitation functions, including ER cross-sections for the following reactions$ ^{12} $ C+$ ^{194} $ Pt,$ ^{12} $ C+$ ^{198} $ Pt,$ ^{18} $ O+$ ^{192} $ Os, and$ ^{16,18} $ O+$ ^{198} $ Pt and survival probabilities for a range of fissilities [36], can be obtained within the framework of this 1D Langevin dynamics with a universal friction parameter. However, it is also important to bear in mind the possible bias originating from experimental uncertainty. It is striking that the observed deviations are pronounced in the ER cross-section data, as the measurements are reported to have a large uncertainty in the ER separator transmission efficiency [15, 23]. It would be highly desirable to conduct additional ER measurements to rule out any possible experimental bias in the interpretation of ER data.It must be noted that the entrance channel dynamics of the fusion stage may also play a role in influencing neutron emission at the formation stage [14]. It is known that the interplay of the CN excitation energy, angular momentum, and the fission barrier plays a crucial role in the fission process [28]. This study does not consider any entrance channel dynamics influencing the fusion stage. The model only considers the entrance channel dependent "l" distribution obtained within the surface friction model [58]. In Fig. 4, we present the calculated fission barrier height

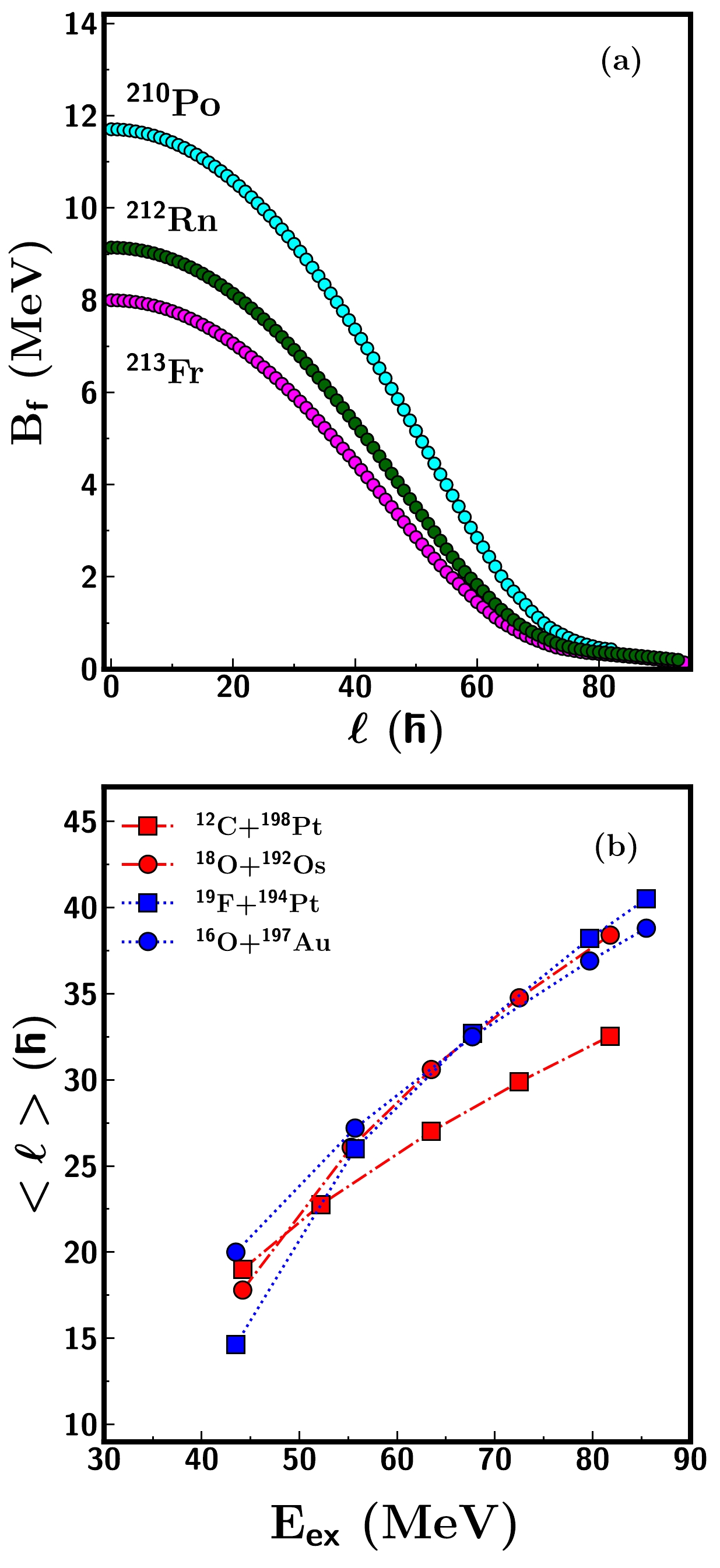

$ B_f(l) $ for three compound systems and the mean angular momentum$ <l> $ calculated based on the "l" distribution for different entrance channels forming the same CN. The variation in$ B_f $ is plotted as a function of "l" in Fig. 4(a), and the variation in$ <l> $ of the compound systems is plotted as a function of$E_{\rm ex}$ in Fig. 4(b). From Fig. 4, it is evident that the difference in angular momenta between two entrance channels forming the same CN at similar$E_{\rm ex}$ is not significant enough to cause any "l" induced effects on the measured fission observable. This is evident in the$\nu_{\rm pre}$ data for$ ^{210} $ Po formed in the reactions$ ^{12} $ C+$ ^{198} $ Pt and$ ^{18} $ O+$ ^{192} $ Os, which can be well described based on the present study (see Fig. 1) without invoking any entrance channel effects in the model. Notably, recent studies investigating entrance channel dynamics [27, 28] have reported disagreements between the experimental$\nu_{\rm pre}$ and predictions of the entrance channel model for$ ^{213} $ Fr nuclei formed via the$ ^{16} $ O+$ ^{197} $ Au and$ ^{19} $ F+$ ^{194} $ Pt reactions. These studies were, however, not extended to other isotopes of Fr, namely$ ^{215,217} $ Fr, which also show a similar discrepancy, as reported in the present study.

Figure 4. (color online) (a) Angular momentum "

$ l $ " dependent fission barrier height$ B_f(l) $ of the following three CN:$ ^{210} $ Po,$ ^{212} $ Rn, and$ ^{213} $ Fr. (b) Variation in the mean angular momentum$ <l> $ with the CN excitation energy for$ ^{210} $ Po and$ ^{213} $ Fr generated by different entrance channels.The current 1D Langevin analysis provides a simultaneous description of the experimental data for the neutron magic nuclei

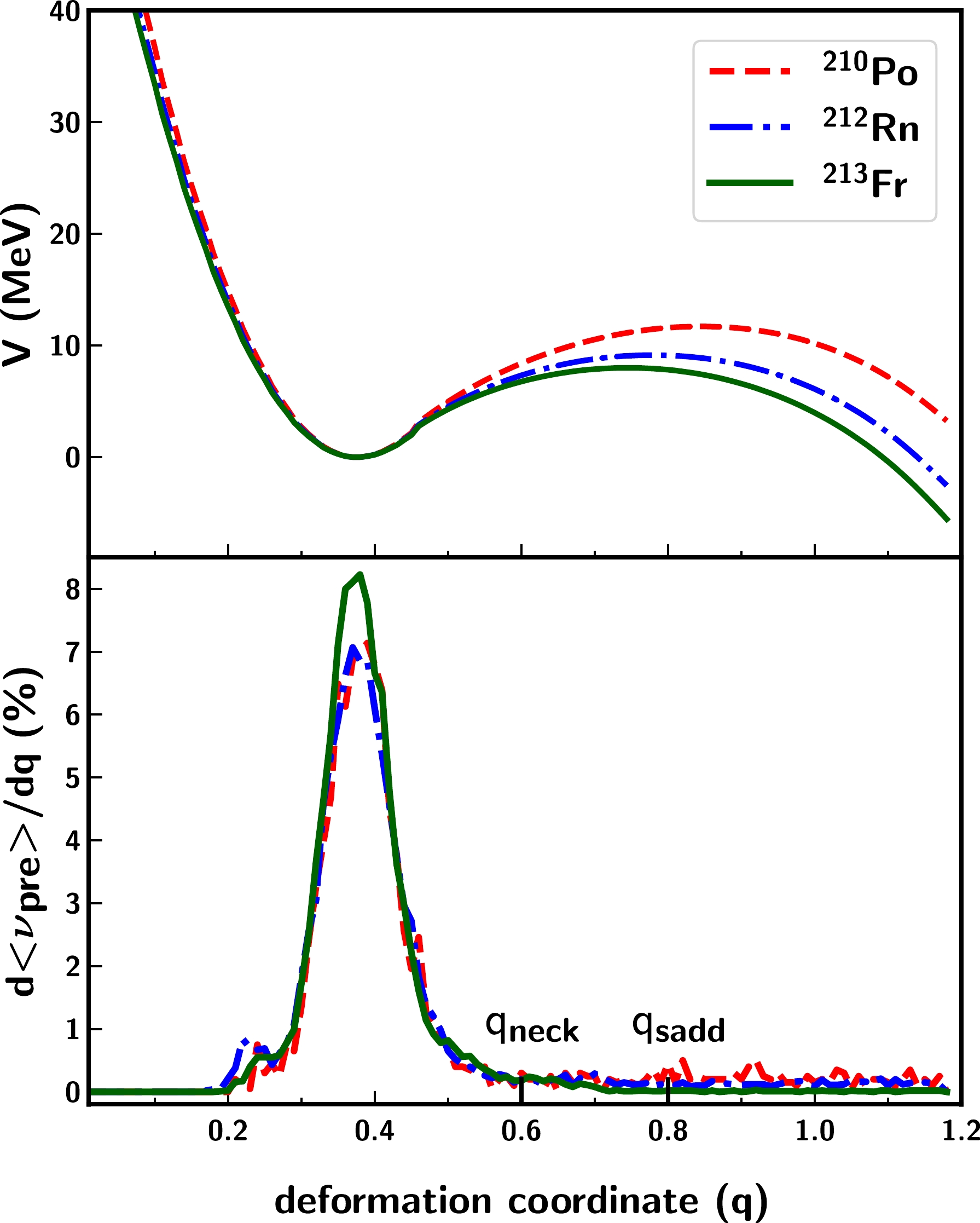

$ ^{210} $ Po without invoking any saddle shell corrections or any nuclear dissipation strength dependent factor in the system/observable under study. To qualitatively understand that considerations of saddle shell corrections are not required to explain the$\nu_{\rm pre}$ data, we consider the nature of neutron emission during the fission process. It is to be noted that these neutrons are emitted from dynamical trajectories that originate from a compact configuration until the scission point is reached. The prompt and beta-delayed neutron emissions from fission fragments are not considered. As recent studies have advocated the inclusion of shell corrections into the saddle configuration to better describe angular anisotropy and$\nu_{\rm pre}$ data at moderate excitation energies [12, 18, 19], we attempted to determine the distribution of pre-scission neutrons as it evolves from the ground state to the scission point. The model calculated potential energy V(q) and the distribution of the percentage yield of pre-scission neutrons are plotted as functions of the deformation coordinate (q) for the considered nuclei at an excitation energy of 50 MeV, and these are shown in Fig. 5. It is evident that more than 90$ \% $ of neutron emission occurs at an early stage of fission before the saddle deformation (q$ \approx $ 0.8) [38] is reached. The mean of the distribution corresponds to the$\nu_{\rm pre}$ emission close to the ground state configuration. In fact, a multi-dimensional Langevin study of$ ^{215} $ Fr conducted by Nadtochy$ et $ $ al $ . [31] also pointed out that a considerable proportion of the pre-scission neutrons is emitted at an early stage of the fission before the saddle is reached. As most of the neutrons are emitted close to the ground state configuration, this is unlikely to be influenced by any shell corrections applied at the saddle.

Figure 5. (color online) Potential energy distribution as a function of the nuclear deformation coordinate (q) for three fissioning nuclei

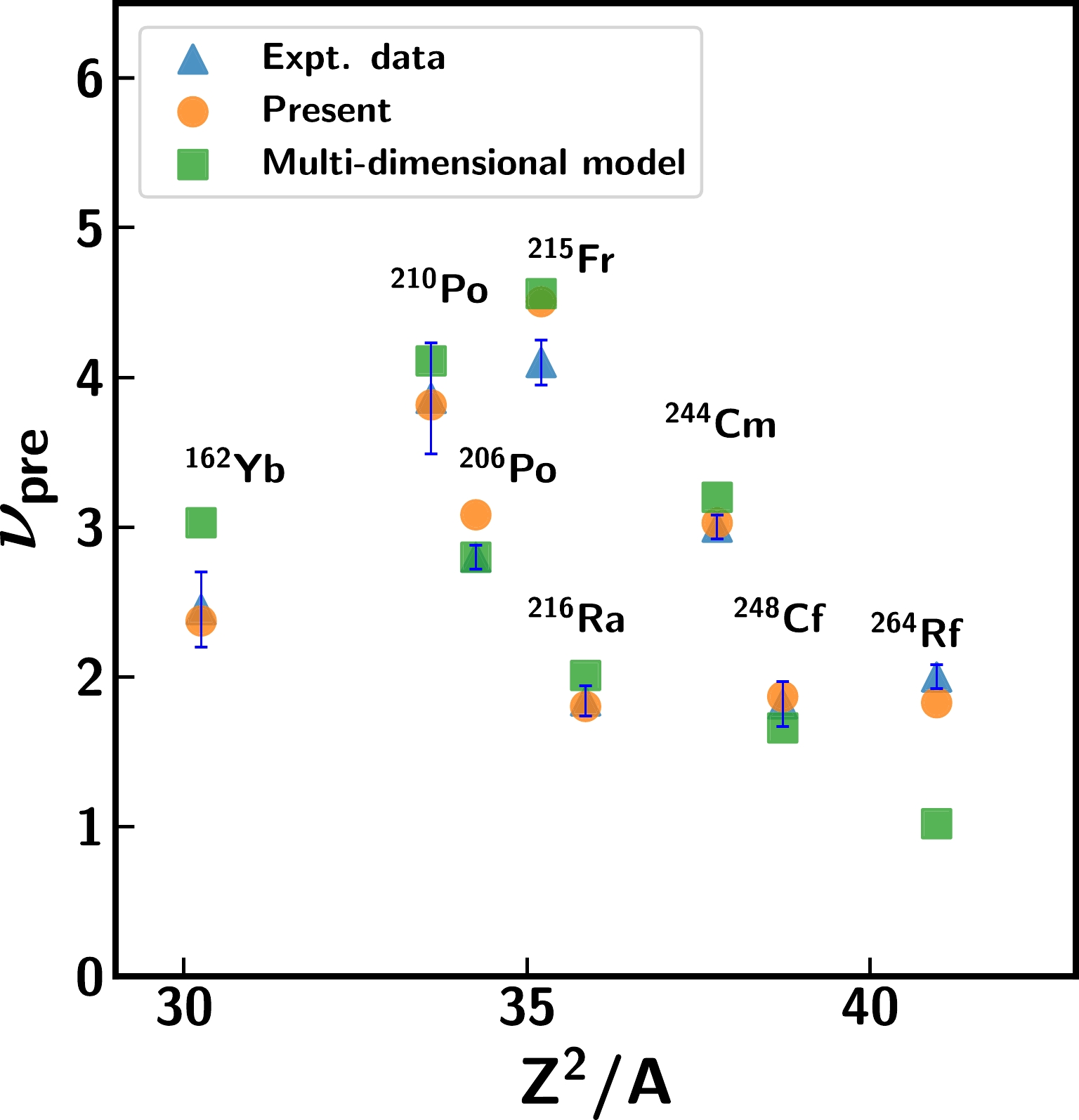

$ ^{210} $ Po,$ ^{212} $ Rn, and$ ^{213} $ Fr (top panel) and distribution of the percentage yield of evaporated pre-scission neutrons as a function of (q) for the three CN at 50 MeV excitation energy (bottom panel). The deformation coordinate (q) assumes a value of 0.6 (q$_{\rm neck}$ ) when the neck of the fissioning nucleus starts to develop and q=0.8 (q$_{\rm sadd}$ ) at the saddle state configuration.Although the present code uses the classical 1D approach to describe the fission observables, the main objective of this study is to provide a simultaneous description of the experimental data without any parameter adjustment, thus eliminating certain reported ambiguities. A comparison between

$\nu_{\rm pre}$ calculated based on the 1D model and recent macroscopic multi-dimensional models is displayed in Fig. 6. It can be observed that the$\nu_{\rm pre}$ values predicted by different models are very similar and also reproduce the measurements quite well for reactions spanning a wide range of the fissility parameter,$ Z^{2}/A $ . Additionally, multi-dimensional calculations [34, 50, 81] also use the formalisms adopted from Refs. [36, 69]; these include a parameterization of the surface friction model and the weakest coordinate dependence of the level-density parameter, as employed in the present study. Hence, the qualitative nature of the observed features presented here is not expected to be different with a multi-dimensional approach. As the present framework is found to provide realistic values that are close to the measured data, we believe that the 1D approach can still serve as a potential tool for studying the wider systematics and that this can be accomplished using minimum computational resources.

Figure 6. (color online) Comparison of measured pre-scission neutron multiplicities (

$\nu_{\rm pre}$ ) with the results of the 1D model (present work) and multi-dimensional models. The filled triangles (blue) denote experimental data [6, 14, 59, 76–79], dynamical model calculations are represented by filled circles (orange), and the filled squares (green) denote the results of multi-dimensional dynamical calculations [28, 30, 34, 80].It must be remarked here that even though the present analysis reasonably reproduces the experimental data without invoking any shell corrections at high excitation energies, we cannot possibly conclude that shell effects are not relevant in the analysis. As the present investigation considers only the first chance fission at

$E_{\rm ex}$ >40 MeV, above which shell effects are expected to be washed out, no indication for the need to include shell corrections was found. However, for the case when the CN is populated at low excitation energies or reaches a low excitation energy owing to neutron emission because of competition between neutron evaporation and fission (multi-chance fission), microscopic effects have to be considered. A recent microscopic study of dissipation within the Hartree-Fock+BCS framework [75] revealed a strong dependence of dissipation on the deformation and initial excitation energies of hot nuclei. The possible influence of the microscopic temperature dependence of the fission barrier height and its curvature has also been emphasized in some recent studies considering a complete microscopic description of the fission process [82, 83]. A microscopic framework based on the finite-temperature Skyrme-Hartree-Fock+BCS approach [84] was adopted in a previous study to demonstrate the essential role of energy dependent fission barriers by studying the experimental fission probability of$ ^{210} $ Po. However, it would be quite interesting to extend the investigation of Fr nuclei within such a microscopic framework. -

In this paper, we report a systematic study on the fission dynamics of N=126 shell closed nuclei in the mass region of 200, with a simultaneous description of three fission observables. The present study highlights the limited reliability of the conclusions drawn from recent statistical model analyses of shell closed nuclei, namely

$ ^{210} $ Po,$ ^{212} $ Rn, and$ ^{213} $ Fr, at excitation energies above 40 MeV, and the analysis advocates the inclusion of extra shell effects at the saddle configuration even after their inclusion in the level density formulation. Notably, previous analyses of$\nu_{\rm pre}$ and the ER cross-sections were based on different assumptions and case dependent parameter adjustments and failed to reach a definite conclusion. Based on the present analysis, we conclude that without several of these assumptions and parameter adjustments, a well established combined dynamical and statistical model can simultaneously reproduce the available data for$\nu_{\rm pre}$ , fission, and ER excitation functions (also fusion cross-sections in certain cases) for neutron shell closed nuclei such as$ ^{210} $ Po and$ ^{212} $ Rn and their non-shell closed isotopes$ ^{206} $ Po and$ ^{214,216} $ Rn without the need of including any extra shell effects. There appears to be no discernible influence of the N$ = $ 126 neutron shell structure on these measured fission observables in the medium excitation energy range. The present analysis also indicates a relatively smaller role of the entrance channel effects in the studied systems.However, we identify a significant mismatch between the measured

$\nu_{\rm pre}$ data and the model predictions for Fr nuclei generated in the reactions$ ^{19} $ F+$ ^{194,196,198} $ Pt and$ ^{16} $ O+$ ^{197} $ Au, despite a reasonable description of the fission and fusion cross-sections. The$\nu_{\rm pre}$ data for Fr nuclei could only be reproduced after invoking a temperature dependent frictional form. The difficulty in completely reproducing some specific measurements of Fr nuclei is still not well understood, and additional measurements are desired. Although the present analysis is limited to the study of three fission observables, it would also be interesting to extend the investigation to a systematic study using the recent microscopic theory within the Hartree-Fock + BCS framework. -

We are thankful to K. S. Golda and N. Saneesh at IUAC for fruitful discussions.

Investigating the fission dynamics of the following neutron shell closed nuclei within a stochastic dynamical approach: 210Po, 212Rn, and 213Fr

- Received Date: 2022-07-27

- Available Online: 2023-03-15

Abstract: The dissipative dynamics of nuclear fission is a well confirmed phenomenon that can be either described by a Kramers-modified statistical model or by a dynamical model employing the Langevin equation. Although dynamical models as well as statistical models incorporating fission delays have been found to explain the measured fission observables in several studies, they present conflicting results for shell closed nuclei in the mass region of 200. Notably, an analysis of the recent data on neutron shell closed nuclei in the excitation energy range of 40

Abstract

Abstract HTML

HTML Reference

Reference Related

Related PDF

PDF

DownLoad:

DownLoad: