-

The large collective flow and momentum anisotropy as manifested in the final hadron spectra in high-energy heavy-ion collisions indicate a strong collectivity of the produced dense and hot nuclear matter during its dynamic evolution [1, 2]. The observed approximate constituent quark number (NCQ) scaling of the elliptic flow for light quark hadrons [3-6] and strong jet quenching [7-10] in high-energy heavy-ion collisions at both the Relativistic Heavy-ion Collider (RHIC) and the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) suggest the formation of a hot, deconfined, and opaque quark-gluon plasma (QGP). Similar phenomena are also observed for heavy quark mesons [11-17]. Experimental data from the RHIC and LHC show a large elliptic flow of

$ D^0 $ mesons at low-$ p_T $ , which also approximately obeys the NCQ scaling of light quark hadrons [13, 18]. Heavy quarks are predominantly produced through initial hard processes and have mass scales much larger than the typical temperature of the QGP medium. Therefore, it still remains an interesting question as to whether and to what degree charm quarks become thermalized [2] and flow with the QGP due to their strong interaction with the hot medium.Past studies usually describe the thermalization processes of heavy quarks with transport equations. Their low-momentum (

$ p\lesssim M $ ) dynamics in the QGP medium are usually treated as Brownian motion [19-21], considering the masses of heavy quarks to be much larger than the typical temperatures in the medium$ M\gg T $ . For the transport of heavy quarks with intermediate momentum$ p\gtrsim M $ , both the collisional and radiative energy loss have to be considered. For high-momentum heavy quarks, most transport models [22-24] consider the gluon radiations and interactions between heavy quarks and the medium as perturbative processes or use transport coefficients with weakly-coupled assumptions as inputs.It was found that transport models need a large heavy-quark momentum-diffusion parameter (

$ \hat{q} = 0.7...2.7 $ GeV$ {}^2/ $ fm at$ T = 300 $ MeV and$ p = 30 $ GeV/c [25]) to describe the observed medium modification of the heavy-quark meson spectra and elliptic flow coefficients [25, 26]. Several studies have attempted to evaluate the heavy quark diffusion coefficient at zero momentum non-perturbatively from lattice QCD [27-29]. The estimated interaction strength is comparable to the values from phenomenological determination [24, 30] and much larger than the natural expectation of the weakly-coupled theory at the leading order. This poses questions regarding the weak-coupling assumption on the nature of the interaction between heavy quarks and the QGP medium. It is possible that, with a strong coupling, the dynamics of the low-$ p_T $ charm quarks in the QGP are better described by a hydrodynamic approach.In this study, we compute the production of low-

$ p_T $ D mesons in an extreme limit of hydrodynamic evolution with the following assumptions. First, the number of (anti)charm quarks is conserved during the lifetime of the fireball, i.e., thermal production of heavy quark pairs is negligible. Second, the coupling is so strong that the initially produced charm quarks quickly diffuse into the QGP and reach local kinetic equilibrium. Finally, the differential yield of D mesons is computed using the Cooper-Frye formula [31] on the hydrodynamic freeze-out hypersurface, with an effective charm chemical potential to guarantee the charm yield is the same as measured in the experiment. We compare the resultant$ p_T $ -dependent spectra and elliptic flow of low-$ p_T $ D mesons, which are considered as the manifestation of the extreme limit of complete thermalization of heavy quarks, to the experimental data as well as transport calculations to quantify the degree of heavy-quark thermalization in heavy-ion collisions. We use the (3+1)D hydrodynamic model (CLVisc) [32] and a linearized Boltzmann-Langevin model [24] for heavy quark transport.The paper is organized as follows. In Section II, we introduce the relativistic hydrodynamic model and the Boltzmann-Langevin transport model for the calculations of

$ p_T $ spectra and elliptic flow of charmed mesons. In Section III, we first discuss the calibration of the hydro model to the experimental data on light quark hadron spectra and elliptic flow in Au+Au collisions at the RHIC energy. We then compare the hydro results on the$ p_T $ spectra and elliptic flow of charmed mesons at low$ p_T $ to the experimental data and transport calculations and discuss the implications on the degree of thermalization for heavy quarks in the QGP formed in high-energy heavy-ion collisions. -

In the usual paradigm for charmed meson production in high-energy heavy-ion collisions, charm quarks are produced through the initial hard scatterings [33]. These heavy quarks experience energy loss and momentum diffusion in the QGP through both elastic and inelastic collisions with the medium, which can be modeled as the drag and diffusion coefficients in the Boltzmann-Langevin equations. The final D mesons are formed through charm quark fragmentation at high

$ p_T $ [34-36] or charm-light quark recombination at low and intermediate$ p_T $ [37]. Such transport models for initial heavy quark and final meson production can describe the charm meson spectra and elliptic flow well in high-energy heavy-ion collisions [25, 26]. However, it is still interesting to investigate whether and to what degree the heavy quarks achieve kinematic equilibrium. If these heavy quarks indeed reach local thermal equilibrium, one should expect that the hydrodynamic model can also describe heavy meson spectra and elliptic flow. Furthermore, a hydrodynamic picture overcomes the difficulty of the transport equation when the coupling becomes large between charm quarks or mesons and the medium.In this study, we consider the extreme scenario and investigate the charmed meson spectra and elliptic flow in the limit of the fully thermalized low-

$ p_T $ charm quarks. These low-$ p_T $ charm quarks are still produced initially through hard processes; however, the interactions are assumed to be strong enough that they quickly diffuse into the medium and lose the memory of their initial distribution in phase space, both in terms of the spatial location and momentum of the initial production through hard processes. In the momentum space, they are assumed to reach full kinetic equilibrium and comove with the medium, flowing with the strongly coupled QGP as light quarks and gluons. Finally, the charm quarks transit to charm hadrons with a phase transition of the bulk medium, where we assume the interaction in the hadronic phase is still strong enough to maintain the kinetic equilibrium and equilibrium ratios of different species of charm mesons. In this situation, the low-$ p_T $ D mesons are produced in the same way as other light hadrons on the freeze-out hypersurface in a relativistic hydrodynamic model. The temperature and fluid velocity profiles on the freeze-out hypersurface are crucial for a reasonable estimate of the D-meson spectra and elliptic flow in the limit of a complete heavy-quark thermalization. We will use the rapidity distribution,$ p_T $ spectra, and elliptic flow of charged pions to calibrate the hydrodynamic model.For completeness, we have to consider

$ D^0 $ mesons from the feed-down of$ D^* $ . Using the feed-down tables from [37, 38],$ D^*(2007)^0 \xrightarrow{64.7{\text{%}}} D^0(1865) + \pi^0, $

(1) $ D^*(2007)^0 \xrightarrow{35.3{\text{%}}} D^0(1865) + \gamma, $

(2) $ D^*(2010)^+ \xrightarrow{68{\text{%}}} D^0(1865) + \pi^+ $

(3) Note that the

$ D^* $ 's are vector mesons with spin 1. Therefore, the spin degeneracy ratio for$ D^* / D $ is$ 3:1 $ . -

The hydrodynamic model we use, CLVisc, is a (3+1)D viscous hydrodynamic model parallelized on GPU using OpenCL [32]. The program is well tested against several analytical solutions and can describe the bulk hadron spectra and anisotropic flow in high-energy heavy-ion collisions at top RHIC and LHC energy. It simulates the fluid dynamic evolution of the strongly interacting QCD matter created in high-energy heavy-ion collisions by solving the fluid dynamic equations

$ \nabla_\mu T^{\mu\nu} = 0, {\ \ {{\rm{with}}}\ \ } T^{\mu\nu} = \varepsilon u^\mu u^\nu - P\Delta^{\mu\nu}+\pi^{\mu\nu}, $

(4) where

$ \varepsilon $ is the energy density, P is the pressure as a function of energy density given by the equation of state (EoS),$ \Delta^{\mu\nu} = g^{\mu\nu}-u^\mu u^\nu $ is a projection operator,$ u^\mu $ is the fluid four-velocity obeying$ u^\mu u_\mu = 1 $ and$ \pi^{\mu\nu} $ is the shear stress tensor.The initial condition for entropy density distribution in the transverse plane is provided by the Trento Monte Carlo model [39, 40]. An envelope function is used to approximate the longitudinal distribution along the space-time rapidity,

$ H\left(\eta_{s}\right) = \exp \left[-\frac{\left(|\eta_{s}|-\eta_{w}\right)^{2}}{2 \sigma_{\eta}^{2}} \theta\left(|\eta_{s}|-\eta_{w}\right)\right], $

(5) where

$ \sigma_{\eta} = 1.5 $ and$ \sigma_{w} = 1.3 $ are used for Au+Au collisions at$ \sqrt{s_{NN}} = 200 $ GeV.We have assumed an initial time for the hydrodynamics

$ \tau_0 = 0.6 $ fm. In the present study, we use the partial chemical equilibrium EoS with chemical freeze-out temperature 165 MeV and a smooth crossover between a QGP at high temperature and hadron resonance gas (HRG) EoS at low temperature [41] as inspired by the lattice QCD study.Baryons and mesons passing through the freeze-out hyper-surface are assumed to obey Fermi-Dirac and Bose-Einstein distributions, respectively. Their momentum distributions are given by the Cooper-Frye formula [31],

$ \frac{{\rm d}N_i}{{\rm d}y p_T{\rm d}p_T{\rm d}\phi} = \frac{g_i}{(2\pi)^3}\int{p^\mu {\rm d}\Sigma_\mu f(p\cdot u)}(1+\delta f), $

(6) where

$ g_i = 2 {\rm{spin}} + 1 $ is the spin degeneracy,$ p^{\mu} $ is the four-momenta of produced particles in the laboratory frame,$ \Sigma_{\mu} $ is the freeze-out hyper-surface,$ f(p\cdot u) $ is the Fermi-Dirac/Bose-Einstein distribution function,$ f(p\cdot u) = \frac{1}{\exp \left[\left(p \cdot u-\mu_{i}\right) / T_{\mathrm{frz}}\right] \pm 1} , $

(7) and

$ \delta f $ is the non-equilibrium correction,$ \delta f = \left(1 \mp f_{\mathrm{eq}}\right) \frac{p_{\mu} p_{\nu} \pi^{\mu \nu}}{2 T_{\mathrm{frz}}^{2}(\varepsilon+P)}. $

(8) We have chosen the freeze-out temperature

$ T_{fz} = 137 $ MeV for light flavor hadrons. The freeze-out temperatures for D mesons are different, and we consider several values to provide an estimate of the uncertainties.The elliptic flow of D mesons is defined as the second coefficient of the Fourier decomposition of their azimuthal angle distributions with respect to the event plane of light hadrons,

$ \frac{{\rm d}^{3} N}{p_{{T}} {\rm d} p_{{T}} {\rm d} y {\rm d} \phi} = \frac{{\rm d}^{2} N}{2 \pi p_{{T}} {\rm d} p_{{T}} {\rm d} y}\left[1+\sum\limits_{n = 1}^{\infty} 2 v_{n} \cos \left(n\left(\phi-\Psi_{\mathrm{EP}}\right)\right)\right]. $

(9) -

We compare the charm meson spectra and flow calculated from the hydrodynamic freeze-out model to that from a transport model [24]. The transport approach assumes that heavy quarks, including those with low momentum in the comoving frame of the medium, remain good quasi-particles in the QGP. Therefore, the dynamics of low-

$ p_T $ heavy flavors can be described by a Boltzmann-type transport equation,$ \begin{aligned}[b] \left(\frac{\partial}{\partial t}+{{v}}\cdot \nabla\right) f_Q(t,{{x}}, {{p}}) =& \int \left[\frac{{\rm d}R}{{\rm d}{{q}}^3}(p+q,q) f_Q(p+q) \right. \\&\left.-\frac{{\rm d}R}{{\rm d}{{q}}^3}(p,q)f_Q(p)\right] {\rm d}{{q}}^3. \end{aligned}$

(10) Here,

$f_Q(t, { x}, { p})$ is the phase-space density of heavy flavors: heavy quarks or heavy mesons (heavy baryons are omitted in this study).${\rm d}R(p,q)/{\rm d}q^3$ is the differential rate for a heavy flavor particle with momentum p to transfer three-momentum${{q}}$ to the local medium with flow velocity u and temperature T.The hydrodynamic and the transport model have both overlapping and distinct regimes of application. Both models contain the equilibrium situation. Compared to the hydrodynamic approach, a transport model also governs the far-from-equilibrium dynamics of heavy flavor particles. The traces of off-equilibrium effects can be important in a finite and expanding plasma with moderate coupling between heavy quarks and the medium. In the meantime, hydrodynamics can describe the evolution with large couplings and in the non-quasiparticle regime, which is beyond the applicability of the transport approach. Therefore, both models provide complementary pictures to understand the experimental data.

The initial charm quark spectrum that initializes the transport equation is obtained from the perturbative QCD based FONLL [42, 43] calculation with EPPS16 nuclear parton distribution function [44]. In the medium above the pseudo-critical temperature (

$ T>T_c $ ), we assume the heavy flavors exist as deconfined heavy quarks. The interaction rate consists of two parts with a comparable contribution to heavy quark energy loss at intermediate$ p_T $ region: collisional processes and medium-induced gluon radiations.Collisional process in the QGP Collisional processes are mainly modeled by two-body scatterings between the heavy quark and medium partons,

$\begin{aligned}[b] \frac{{\rm d}R_{i = q,g}}{{\rm d}{{q}}^3} =& \int \overline{|M_{Qi\rightarrow Q'i'}^2|}\frac{d_i f(p_i)}{16\pi^2 E_QE_Q'} \frac{{d}^3p_i}{2E_i} \frac{{d}^3p_i'}{2E_i'} \\&\times\delta^{(4)}(p_Q+p_i-p_Q'-p_i'), \end{aligned} $

(11) where Q (i) and

$ Q' $ ($ i' $ ) labels the initial and final state heavy quark (medium quark or gluon).${{{p}}_{{Q}}'} = {{{p}}_{{Q}}}+{{q}}$ is the three-momentum transfer to the heavy quark.$ \overline{|M_{Qi\rightarrow Q'i'}^2|} $ is the squared amplitude of the two-body collision at leading order, averaging over the initial-stage quantum number and summed over the final-state quantum number. The$ \hat{t} $ -channel divergence is screened using the QCD non-perturbative scale$ \Lambda = 0.2 $ GeV and the Debye screening mass$ m_D = \sqrt{6\pi\alpha_s} T $ of a three-flavor plasma,$ \overline{|M_{Qi\rightarrow Q'i'}^2|} \sim \frac{1}{\hat{t}^2} \rightarrow \frac{1}{(\hat{t}-\Lambda^2)(\hat{t}-m_D^2)}. $

(12) Finally,

$f(p_i) = {\rm e}^{-p_i\cdot u/T}$ is the classical thermal distribution function of the medium parton in plasma with local four-velocity u and temperature T, obtained from hydrodynamic simulations. The degeneracy factors for medium quarks and gluons are$ d_g = 2 d_A = 16 $ and$ d_q = $ $ 4 N_f N_c = 36 $ , respectively. Besides perturbative scatterings, an additional effective heavy-quark diffusion constant of the form$ \frac{\Delta \kappa_D}{T^3} = A+\frac{B}{ET} $

(13) is introduced to mimic a possible non-perturbative contribution that peaks at low energy and low temperature. The effective heavy-quark-medium coupling parameter and the parameters in the non-perturbative diffusion constant are tuned in [24] to the suppression and momentum anisotropy of the production of open heavy flavor particles.

Medium-induced radiative process in the QGP phase Heavy quarks can radiate additional gluons in the collision with medium partons. This is treated similarly to the rate in Eq. (11) for collisional processes, using two-to-three-body matrix-elements. One complication is that energetic gluon radiation in the rest frame of the medium is suppressed due to the QCD Landau-Pomeranchuk-Migdal (LPM) effect. In [24], this was included by restricting the phase-space of the radiated gluon using an interference factor motivated by the Higher-Twist approach

$ 2[1-\cos( t/\tau_f)] $ , where t is the time since the last gluon radiation, while$ \tau_f = 2x(1-x)E_Q/(k_\perp^2+x^2M^2) $ is the gluon formation time. Despite the LPM suppression, the radiative energy loss was found to be equally important in the intermediate$ p_T $ region.Heavy quark hadronization and hadronic rescattering At the pseudo-critical temperature, charm quarks hadronize to D-mesons through both fragmentation and recombination mechanisms [45]. In the hadronic phase, D-mesons continued to interact with the light mesons via D-

$ \pi $ and D-$ \rho $ scatterings [46] as implemented in Ultra-relativistic Quantum Molecular Dynamics (UrQMD) [47, 48]. -

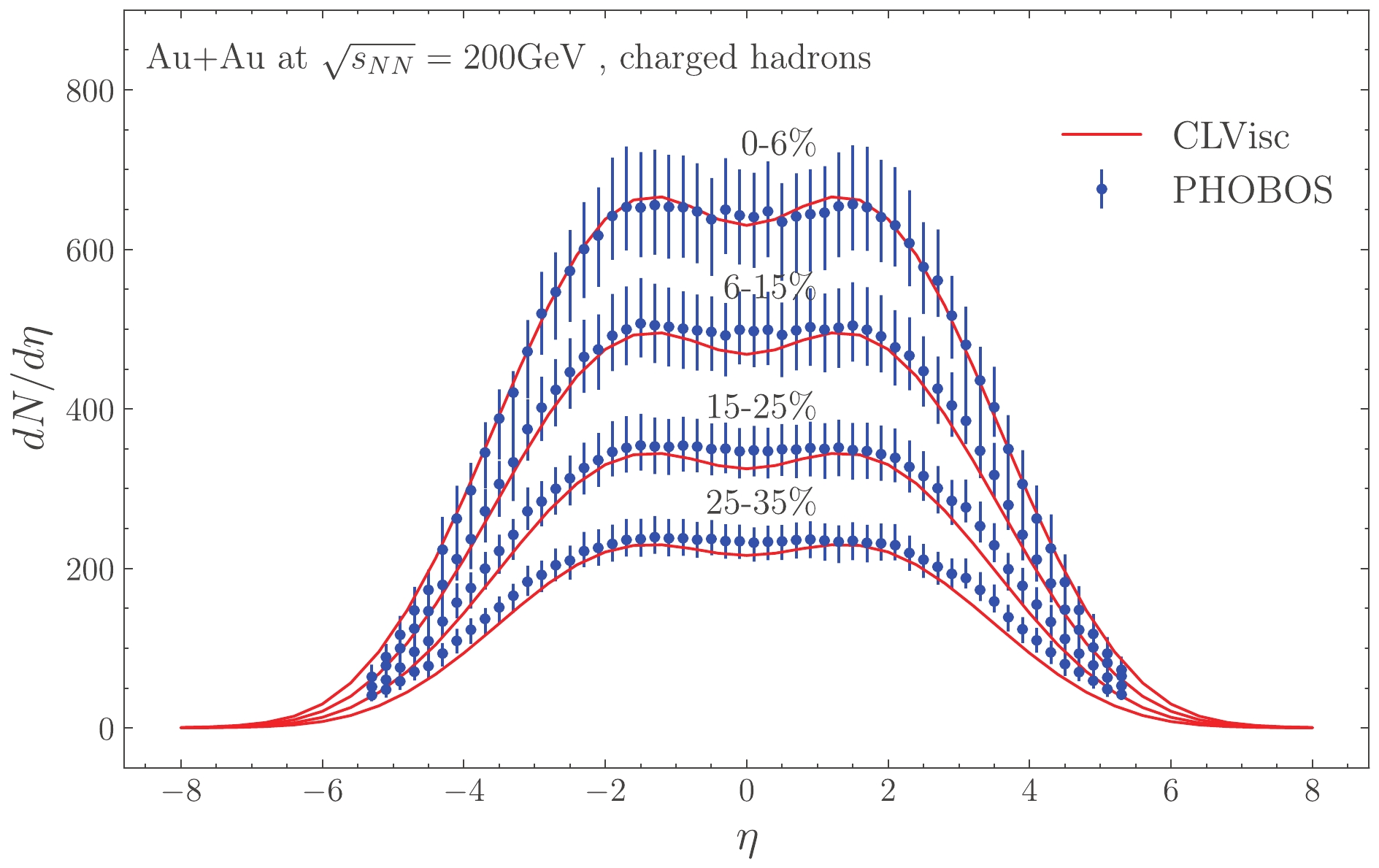

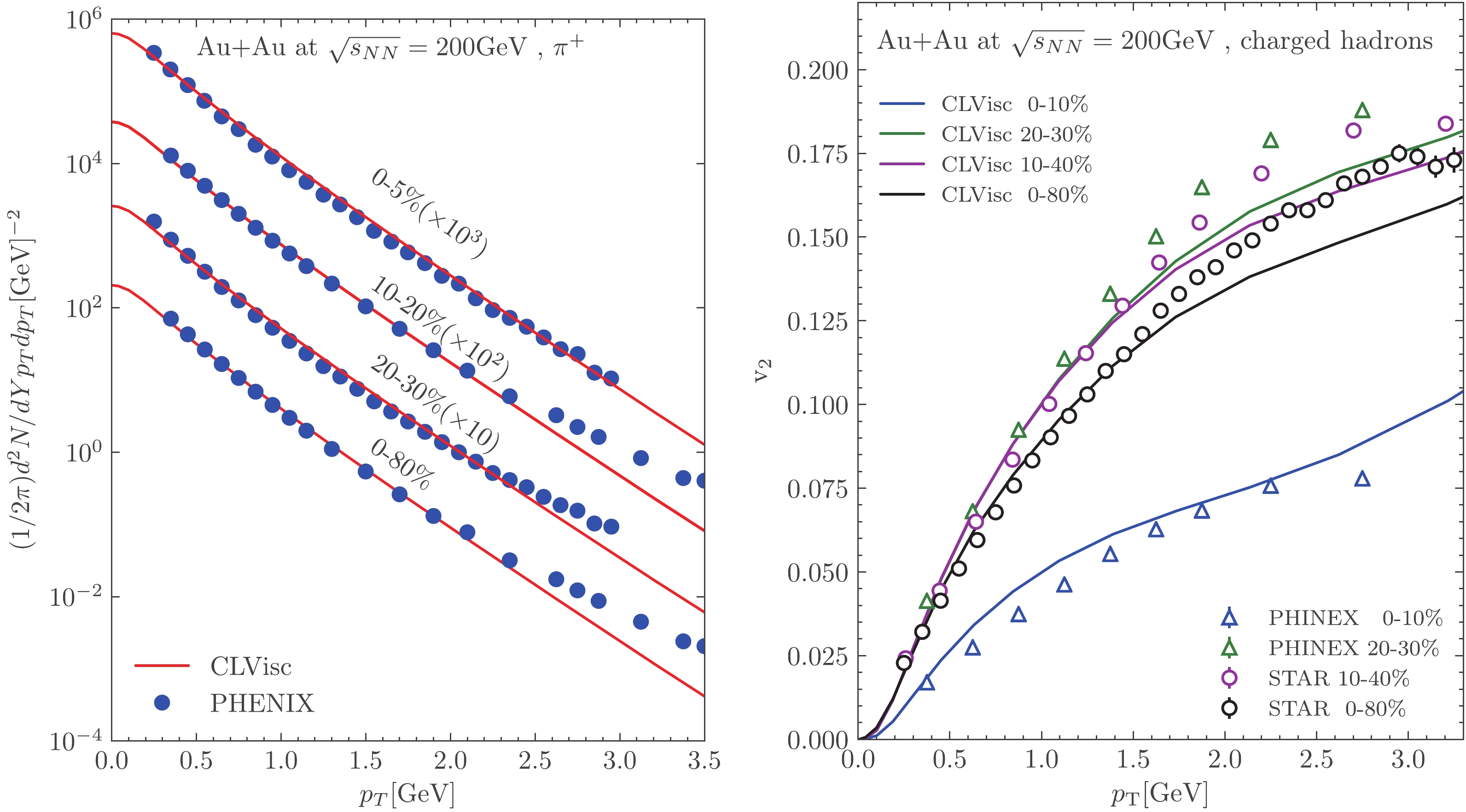

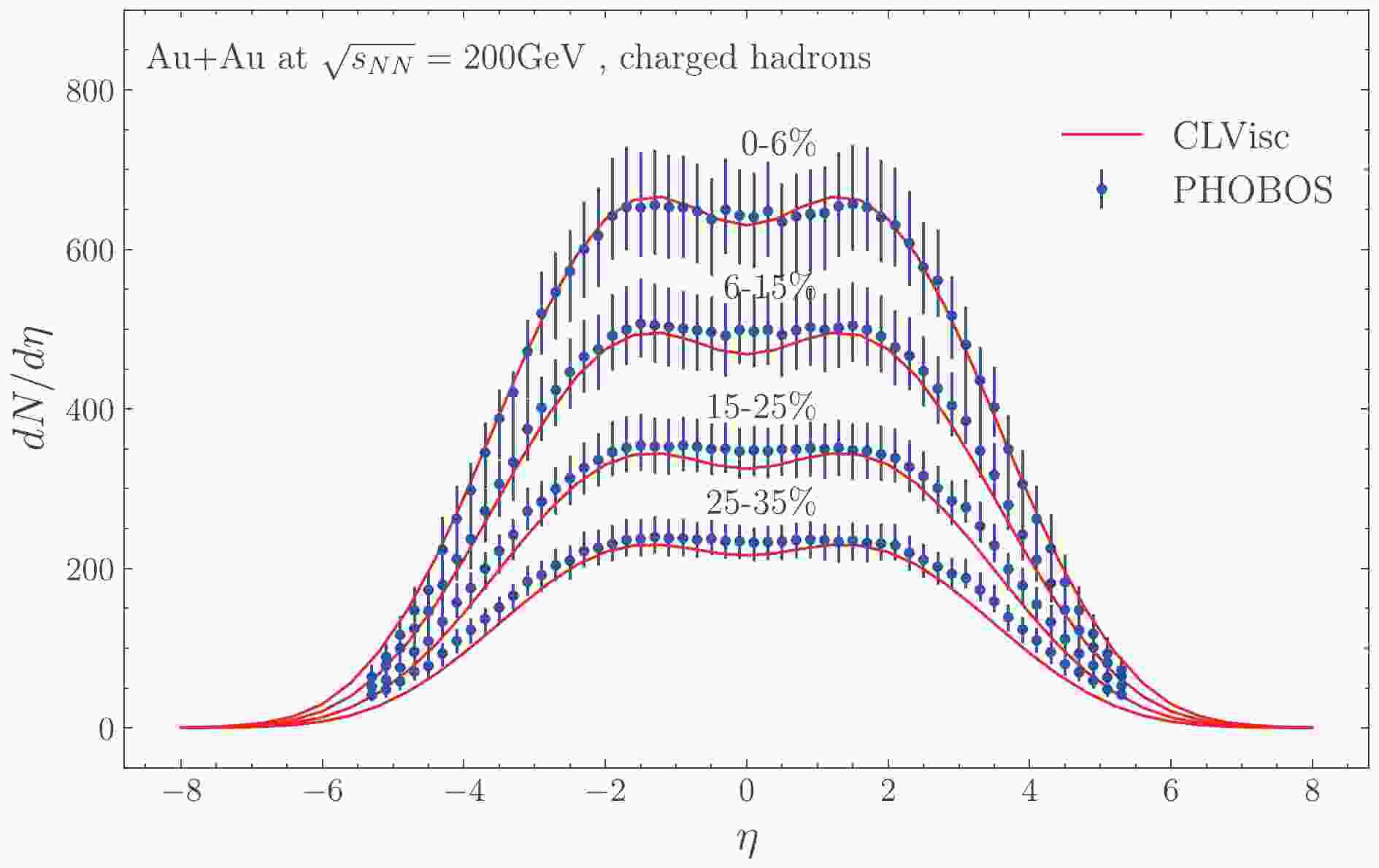

To calibrate the relativistic hydrodynamic model, we have computed the pseudorapidity density of charged particles

${\rm d}N_{ \rm{ch}}/{\rm d}\eta$ as shown in Fig. 1, and the$ p_T $ spectra and the elliptic flow$ v_2 $ of$ \pi^+ $ as shown in Fig. 2 for central Au+Au collisions with centrality range 0-5% at$ \sqrt{s_{NN}} = 200 $ GeV. The calibrated parameters are the scale factor of 53 multiplied to the initial entropy density from the Trento model [39, 40], the starting time for hydro$ \tau_0 = 0.6 $ fm, the shear viscosity over entropy density ratio$ \eta/s = 0.15 $ , and the freeze-out temperature for light hadrons$ T_{fz} = 137 $ MeV. These values have been tuned such that the predicted${\rm d}N_{ \rm{ch}}/{\rm d}\eta$ ,$ p_T $ spectra and$ v_2(p_T) $ of charged pions from relativistic hydrodynamics agree with the experimental data. Relativistic hydrodynamics with the same set of parameters also describes data well at other centralities and we refer readers to Ref. [32] for a more detailed description of CLVisc and the parameters. These parameters are fixed in the following calculations of the heavy quark meson spectra, except the freeze-out temperatures for D mesons. We will vary the value of the D meson freeze-out temperature and study its effect on the final D meson spectra and the elliptic flow.

Figure 1. (color online) Pseudorapidity density of charged hadrons from integrating the Cooper-Frye formula over the freeze-out hyperspace obtained in the CLVisc calculation. It agrees with the data of the PHOBOS experiment for Au+Au collisions at

$ \sqrt{s_{NN}} = 200 $ GeV [49].

Figure 2. (color online) Left: transverse momentum spectra of

$ \pi^+ $ in Au+Au collisions. Right: anisotropic flow coefficient$ v_2 $ in Au+Au collisions using the event-plane method. In both panels, CLVisc calculations (lines) are compared to data from the PHENIX experiment [50] and STAR experiment [51]. -

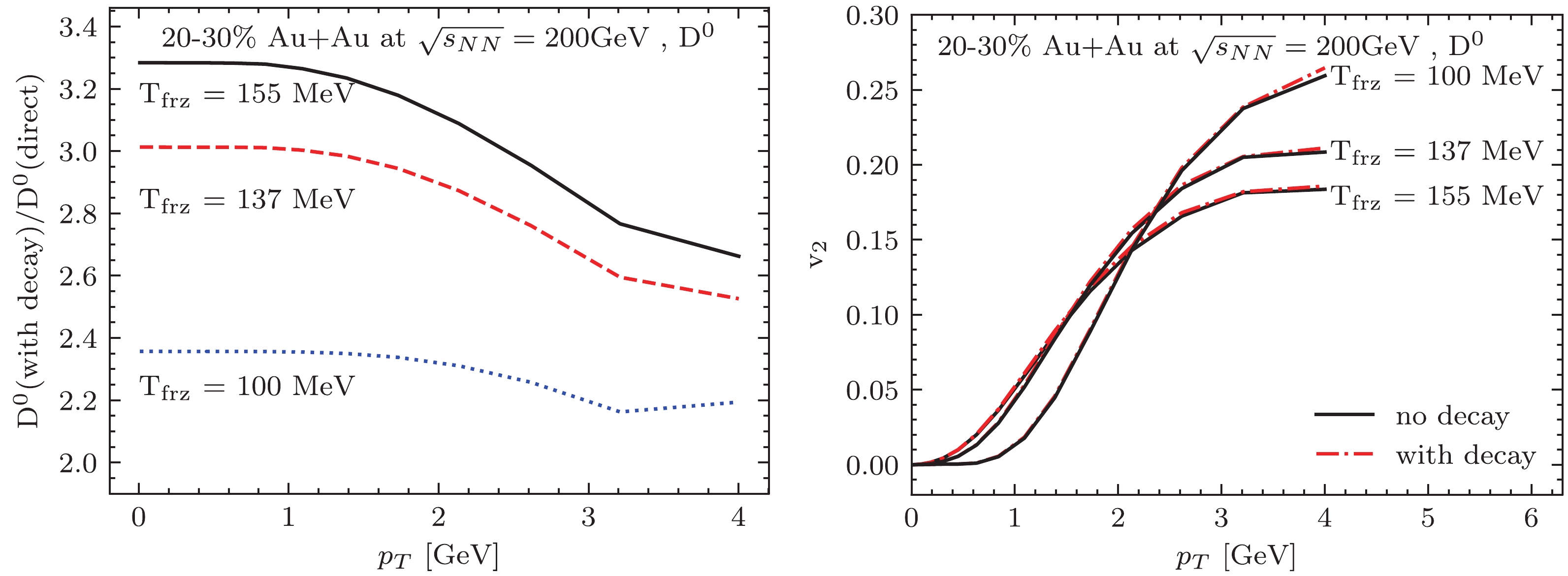

The effects of freeze-out temperature and resonance decays on

$ D^0 $ meson production are studied in this section. In the left panel of Fig. 3, we show the ratio between$ D^0 $ $ p_T $ spectra with and without contributions from the resonance decays. In the right panel of Fig. 3, we compare the$ D^0 $ meson elliptic flow as a function of$ p_T $ with (dot-dashed) and without (solid) resonance decays for three different values of the D meson freeze-out temperatures,$ T_{fz} = $ 100, 137, and 155 MeV. We see that the resonance decay has a much larger effect on the$ p_T $ spectra of$ D^0 $ (left panel) than that on the elliptic flow$ v_2 $ of$ D^0 $ (right panel). For a given D meson freeze-out temperature, resonance decays from$ D^{*} $ contribute more$ D^0 $ mesons at low$ p_T $ than that at high$ p_T $ . The ratio between$ D^0 $ with and without decay decreases as$ p_T $ increases for all three freeze-out temperatures considered here. As one increases the freeze-out temperature from$ 100 $ MeV to$ 137 $ MeV and$ 155 $ MeV, not only the$ D^0 $ yield but also the ratio between$ D^0 $ with and without decay increases, from approximately$ 2.35 $ to$ 3.0 $ and$ 3.3 $ at$ p_T<1 $ GeV. The elliptic flow without decay (black solid), in contrast, almost overlaps that with decays (red dash-dotted) for all three different freeze-out temperatures; therefore, it is insensitive to the contributions from the resonance decays. The freeze-out temperature, however, has a large effect on the shape and magnitude of the elliptic flow as a function of transverse momentum. At small transverse momentum ($ p_T $ < 2 GeV), the elliptic flow increases with the freeze-out temperature. At large transverse momentum ($ p_T $ > 2 GeV), the trend goes the opposite way – the elliptic flow decreases as the freeze-out temperature increases.

Figure 3. (color online) Left: freeze-out temperature dependence of the effect of resonance decay on the

$ D^0 $ $ p_T $ spectra. Right: freeze-out temperature dependence of the effect of resonance decay on the$ D^0 $ flow coefficient$ v_2 $ . Calculations in both panels use one-shot hydrodynamic simulation of 20%-30% central Au+Au collisions at$ \sqrt{s_{NN}} = 200 $ GeV. -

In Fig. 4, we show the hydrodynamic calculations of the transverse momentum (

$ p_T $ ) spectra (left) and the$ p_T $ -dependent elliptic flow (right) of$ D^0 $ mesons in Au+Au collisions at$\sqrt{s_{NN}} = 200$ GeV for different centralities as compared with the results of the transport approach and experimental data from the STAR experiment [12]. As the thermal production of charm quark pairs is negligible in the QGP at the temperatures reached in heavy-ion collisions at the RHIC and LHC colliding energies, we assume the charm quark number from the initial hard processes is conserved via an introduction of charm chemical potential at the freeze-out. The value of the chemical potential$ \mu_c $ at the freeze-out temperature$T_{\rm frz}$ is adjusted to fit the magnitude of the experimental data on the$ p_T $ spectra at low$ p_T $ in the most central collisions. For$T_{\rm frz} = 150$ MeV, the effective charm chemical potential$ \mu_c = 700 $ MeV is found to fit the experimental data on$ D^0 $ spectra (red) at low$ p_T $ ($p_T < 1\ {\rm GeV}$ ) for 0-10% (solid), 10%-40% (dot-dashed), and 0-80% (dashed) centrality. With the same freeze-out temperature and the effective charm chemical potential in the most central collisions, the hydrodynamic model can describe the low$ p_T $ spectra well at other centralities. However, the hydro calculations overpredict the$ p_T $ spectra at$ p_T>1 $ GeV/c.

Figure 4. (color online) Left: hydrodynamic calculations (lines) of

$ D^0 $ $ p_T $ spectra in Au+Au collisions at$\sqrt{s_{NN}} = 200$ GeV for three different centrality bins, using two different sets of freeze-out temperatures and effective charm chemical potentials. They are compared to transport calculations in the same collision system (blue bands) and data from the STAR experiment [12]. We also compare the D-meson production in p+p collisions from FONLL calculation (green band) [42, 43] to the STAR measurement [52]. Right: hydrodynamic calculations of$ D^0 $ meson$ v_2 $ are compared to transport calculations and STAR data [13].Different hadrons can freeze-out at different temperatures in the hydrodynamic model of hadron production. For example, it was shown in the UrQMD model studies that protons freeze-out earlier than pions and kaons [53]. In the hydro calculation of

$ D^0 $ spectra (red in the left panel), we have assumed that$ D^0 $ mesons freeze out ($T_{\rm frz} = 150$ MeV) earlier than the light quark hadrons ($T_{\rm frz} = 137$ MeV). If we set the freeze-out temperature of$ D^0 $ the same as that of the light quark hadrons at 137 MeV with a re-adjusted charm chemical potential$ \mu_c = 800 $ MeV, the slope of the$ p_T $ spectra becomes slightly larger (blue) due to increased radial expansion, further away from experimental data. Increasing the freeze-out temperature slightly decreases the slope of the spectra at high$ p_T $ . However, the change is too small to describe the data at high$ p_T $ .In the left panel of Fig. 4, we further compare the transport calculations (blue bands) of the

$ D^0 $ spectra in Au+Au collisions. Before discussing the results in Au+Au collisions, it is necessary to present the FONLL calculation of the baseline$ D^0 $ spectra (green band) in p+p collisions. The$ D^0 $ meson spectra in p+p collisions are computed using the FONLL program [42, 43], for which major uncertainty stems from the variation of the renormalization scale$ m_T/2<\mu_R<2m_T $ , where$ m_T = \sqrt{M^2+p_T^2} $ is the transverse mass of the heavy quark. From Fig. 4, the central prediction from FONLL (green line) systemically underestimates the STAR data on$ D^0 $ production in p+p collisions at low$ p_T $ , while the upper band of the prediction with$ \mu_R = m_T/2 $ is found to be closer to the measurements. Moving to results for nuclear collisions, we can see that the transport approach, which includes effects of non-equilibrium evolution, describes the experimental data on$ p_T $ spectra at large$ p_T>2 $ GeV/c. At low$ p_T $ , the calculations are still consistent with experiments within error bands; however, the central points of the band under-predict the experimental data. We comment that the production of low-$ p_T $ D mesons in nuclear collisions is sensitive to the small-x region of the nuclear parton distribution function (nPDF), which is less well-constrained than the parton distribution function of the proton. Despite the EPPS16 nPDF publishing its uncertainties, we have only shown calculations using the central fit of the EPPS16 nPDF.Comparison of the high-

$ p_T $ part of the spectra between the hydrodynamic results and experimental data shows that charm quarks have not reached complete equilibrium for$ p_T>1 $ GeV/c, as the spectra from experiments are still below the hydrodynamic results, assuming a fully equilibrated system of charm quarks that flow with the QGP fluid. The enhanced ratios of$ \Lambda_c / D^0 $ and$ D_s/D^0 $ observed at the RHIC [54, 55] for$\rm Au+Au$ collisions and LHC [56, 57] for$\rm Pb+Pb$ collisions as compared with$ p+p $ collisions may partially contribute to this$ D^0 $ suppression [58-61].Both the relativistic hydro and transport models can describe the experimental data on the elliptic flow of

$ D^0 $ mesons within the error bars as shown in the right panel of Fig. 4. One can see the mass ordering of the elliptic flow by comparing it to the elliptic flow of charged pions (blue) from the same hydrodynamic calculations. The hydrodynamic results on$ v_2(p_T) $ at low$ p_T $ are insensitive to the value of the freeze-out temperature.We stress that even though the hydrodynamic model fails to describe the

$ p_T $ spectra of$ D^0 $ beyond$ p_T>1 $ GeV/c, its results on the elliptic flow agree with the experimental data and transport model calculation (solid blue) for$ p_T $ up to 4 GeV/c. This implies that the experimental data on the elliptic flow cannot provide a stringent constraint on the kinetic equilibration of heavy quarks. The strong interaction between heavy quarks and the medium, however, can "drag" the heavy quarks along collective flow developed for the bulk medium even though the interaction might not drive the heavy quarks to full kinetic equilibration. -

We have calculated the

$ D^0 $ meson spectra and elliptic flow in Au+Au collisions at the RHIC energy within a relativistic viscous hydrodynamic model assuming that charm quarks initially produced through hard processes become fully kinetically equilibrated in the QGP. We neglect the thermal charm quark pair production in the QGP and use an effective charm chemical potential at the freeze-out, which is tuned to describe the number of charm quarks produced in the initial hard processes. With the charm freeze-out temperature$ T_{\rm frz} = 137-150 $ MeV, the hydrodynamic model can describe the experimental data on$ D^0 $ elliptic flow for$ p_T<4 $ GeV/c as well as the elliptic flow of light quark hadrons. The mass ordering of the elliptic flow for pions and D mesons in the experimental data is also observed for a freeze-out temperature between 137 and 150 MeV. We have also compared the hydrodynamic results with those from a transport model with both energy loss and momentum diffusion, which can describe the observed elliptic flow of$ D^0 $ mesons at both low and high$ p_T $ .The hydrodynamic model, however, fails to describe the

$ p_T $ spectra of$ D^0 $ for$ p_T>1 $ GeV/c, significantly over-predicting the$ D^0 $ $ p_T $ spectra at large$ p_T $ . The transport model, in contrast, can describe the$ p_T $ spectra well at large$ p_T> $ 2 GeV/c due to parton energy loss. However, its central values under-predict the spectra at low$ p_T $ due to the baseline spectra of the initial charm production through hard processes in p+p collisions.Our comparative study indicates that only the low-

$ p_T $ D mesons in the experiments might have reached kinetic equilibrium while charm quarks in the intermediate region of$ p_T $ are partially thermalized. Parton energy loss and momentum diffusion in the transport model can describe well the non-equilibrium behavior of D mesons spectra and elliptic flow at large$ p_T $ . The interaction of charm quarks in partial equilibrium with the medium in the intermediate$ p_T $ , however, can develop an elliptic flow as large as that of fully equilibrated charm quarks.

Hydrodynamic description of D meson production in high-energy heavy-ion collisions

- Received Date: 2021-01-05

- Available Online: 2021-07-15

Abstract: The large values and constituent-quark-number scaling of the elliptic flow of low-

Abstract

Abstract HTML

HTML Reference

Reference Related

Related PDF

PDF

DownLoad:

DownLoad: