-

The mass and half-life of an atomic nucleus play an important role in nuclear structure and astrophysics, as well as in fundamental interactions and symmetries [1], which reflect all the interactions between constituent nucleons. The presently unknown nuclear masses, particularly those of nuclides far from β-stability, are required to better understand the formation of elements in the universe [2]. For instance, accurate mass values, together with other information on N = Z (A = 78−100) nuclei, are crucial for the investigation of the rp-(rapid proton capture) and αp-processes. Simultaneously, they are employed for solve many key questions related to nuclear structure, including the origin of Wigner energy, T = 0 pairing, isospin symmetry, location of proton drop lines, evolution of deformation and shell closure, testing of mass models, constraints on the B (GT) value of beta decay along N = Z, and testing of the CVC hypothesis. However, such nuclei, characterized by low production cross-sections and short half-lives, are extremely difficult to produce and measure in a laboratory. Therefore, highly efficient measurement techniques and facilities are required. Storage ring mass spectrometers offer the possibility of simultaneous mass and half-life measurements of these short-lived nuclides. There are three such heavy-ion storage rings in operation worldwide, named the experimental storage ring ESR at GSI Helmholtz Center in Darmstadt [3], experimental Cooler Storage Ring CSRe at the Institute of Modern Physics in Lanzhou [4], and Rare-RI Ring R3 at the RIKEN Nishina Center in Tokyo [5].

To extend the mass and half-life measurement program to nuclei with even smaller production rates, the Spectrometer Ring (SRing) is being designed for the next-generation High Intensity heavy-ion Accelerator Facility (HIAF), which will be located in Huizhou, China [6, 7]. The HIAF will provide a high-intensity, high-quality, and higher-energy heavy-ion beam with the synchrotron Booster Ring (BRing). The transmission line between the BRing and SRing is both a transmission line between the two rings and a high-magnetic-rigidity (25 Tm) radioactive secondary beam line HIAF FRagment Separator (HFRS). The stable nuclear heavy ion beam extracted from BRing is targeted to produce a radioactive secondary beam, which can be directly used for experimental measurement after separation and selection by HFRS, or the isolated unstable nuclear secondary beam can be injected into the SRing to prepare high-quality secondary beams for high-precision experimental measurements.

Three operation modes have been carefully designed for the SRing: isochronous mode, normal mode, and internal target mode. The isochronous mode is specially designed for in-ring high-precision mass measurements of exotic nuclei with low production cross-sections and short half-lives. The normal mode is designed to prepare high-quality Rare Isotope Beams (RIBs) for Schottky mass spectrometry experiments and in-ring atomic physics experiments. The internal target mode is designed mainly for reaction studies utilizing the gas-jet target (GJT) and specific electron target (ET). In the isochronous mode, short half-life nuclei, especially neutron-rich nuclei far away from β decay stability, can be produced by HFRS via projectile fragmentation reactions. After in-flight separation and transmission, the secondary beams are finally injected and stored in the SRing for mass and half-life measurements of exotic nuclei. For instance, measuring the masses of nuclides around

$ {}^{78} {\rm{Ni}}$ ,$ {}^{122} {\rm{Zr}}$ , and$ {}^{132} {\rm{Sn}}$ , as well as the lifetime and nuclear reaction rates of the associated nuclei, will be a crucial task for the application of isochronous mode.In the storage ring mass spectrometry, the circulating ions follow Eq. (1), which connects the revolution times (T) of the circulating ions to their mass-to-charge ratios (

$ m/q $ ) and velocities (v) [8, 9]:$ \frac{\Delta T}{T} = \frac{1}{{\gamma_{t}}^{2}}\frac{\Delta (m/q)}{m/q} + \Biggl(\frac{{\gamma}^{2}}{{\gamma_t}^{2}}-1\Biggr)\frac{\Delta v}{v}+\Biggl(\frac{{\rm d}T}{T}\Biggr)_{\rm add} ,$

(1) where γ is the relativistic Lorentz factor of the circulating ions, and

$ \gamma_t $ is the transition energy of the storage ring.$ ({\rm d}T/T)_{\rm add} $ are additional aberrations to the revolution time spread.As revealed in Eq. (1), to accurately measure the

$ m/q $ values of the circulating ions, one must measure their revolution time or frequency under the condition that the second and third terms on the right side of Eq. (1) can be reduced to a negligible value. There are two methods to reduce the influence of the second term [10]. The first method is Schottky Mass Spectrometry (SMS), which is based on the reduction of the velocity spread$ \Delta v/v $ by applying beam cooling. Beam cooling requires several seconds, which sets a limit on the half-life of the measured nuclide. This method has been employed routinely at the ESR at GSI [11−15]. Another method is Isochronous Mass Spectrometry (IMS), which is based on the isochronous setting that the$ \gamma_t $ of the storage ring is equal to γ of the nuclides of interest. In the isochronous setting, the velocity difference of the circulating ions can be compensated by the difference of their corresponding orbit lengths, giving them the same revolution times. The IMS method is ideally suited for mass measurement of very short-lived nuclides ($ \rm {\mu\text{s}} $ to$ \rm ms $ ) because one measurement takes only a few hundred microseconds. This method has been employed at both the ESR and CSRe [9, 16−19].The ions of interest are injected into the ESR or CSRe with

$ \gamma_t = \gamma = 1.41 $ or$ 1.395 $ , respectively. The achieved mass resolving powers of IMS were approximately$ R({\rm FWHM}) \leq 2\times 10^{5} $ (ESR) and$ R({\rm FWHM}) \leq 5\times 10^{5} $ (CSRe), compared to$ R({\rm FWHM}) \leq1\times 10^{6} $ obtained in SMS experiments [20, 21]. R is the mass resolving power, which is defined as follows:$ R({\rm FWHM}) = \frac {m}{\Delta m} = \frac{1}{2.355}\frac{1}{\gamma_t^{2}}\frac{T}{\sigma (T)}. $

(2) In the SRing, both the SMS and IMS are used to accurately measure the mass and half-life of the short-lived nuclei. The design goal for the SMS of the SRing is to reach a final equilibrium momentum spread at the level of

$ 2\sigma (p)/p = \pm 6\times 10^{-7} \sim 10^{-5} $ using the stochastic and electron cooling systems. Meanwhile, the design goal for the IMS of the SRing is to reach a maximum mass resolution of$ 1\times 10^{6} $ ($ {\rm FWHM} $ ) for the nuclei of interest. To achieve this, a careful design of the isochronous mode of the SRing was carried out.The paper introduces the basic isochronous mode design as well as detailed higher-order isochronous corrections of the SRing. By applying higher-order isochronous corrections, a mass resolution of

$ R({\rm FWHM}) = 1\times10^{6} $ corresponding to a relative revolution time of$ \sigma(T)/T \sim 4.9\times 10^{-7} $ is provided by the isochronous setting$ \gamma_t = 1.43 $ within the momentum acceptance of$ \pm0.2$ %. -

The mass and half-life of an atomic nucleus play an important role in nuclear structure and astrophysics, as well as in fundamental interactions and symmetries [1], which reflect all the interactions between constituent nucleons. The presently unknown nuclear masses, particularly those of nuclides far from β-stability, are required to better understand the formation of elements in the universe [2]. For instance, accurate mass values, together with other information on N = Z (A = 78−100) nuclei, are crucial for the investigation of the rp-(rapid proton capture) and αp-processes. Simultaneously, they are employed for solve many key questions related to nuclear structure, including the origin of Wigner energy, T = 0 pairing, isospin symmetry, location of proton drop lines, evolution of deformation and shell closure, testing of mass models, constraints on the B (GT) value of beta decay along N = Z, and testing of the CVC hypothesis. However, such nuclei, characterized by low production cross-sections and short half-lives, are extremely difficult to produce and measure in a laboratory. Therefore, highly efficient measurement techniques and facilities are required. Storage ring mass spectrometers offer the possibility of simultaneous mass and half-life measurements of these short-lived nuclides. There are three such heavy-ion storage rings in operation worldwide, named the experimental storage ring ESR at GSI Helmholtz Center in Darmstadt [3], experimental Cooler Storage Ring CSRe at the Institute of Modern Physics in Lanzhou [4], and Rare-RI Ring R3 at the RIKEN Nishina Center in Tokyo [5].

To extend the mass and half-life measurement program to nuclei with even smaller production rates, the Spectrometer Ring (SRing) is being designed for the next-generation High Intensity heavy-ion Accelerator Facility (HIAF), which will be located in Huizhou, China [6, 7]. The HIAF will provide a high-intensity, high-quality, and higher-energy heavy-ion beam with the synchrotron Booster Ring (BRing). The transmission line between the BRing and SRing is both a transmission line between the two rings and a high-magnetic-rigidity (25 Tm) radioactive secondary beam line HIAF FRagment Separator (HFRS). The stable nuclear heavy ion beam extracted from BRing is targeted to produce a radioactive secondary beam, which can be directly used for experimental measurement after separation and selection by HFRS, or the isolated unstable nuclear secondary beam can be injected into the SRing to prepare high-quality secondary beams for high-precision experimental measurements.

Three operation modes have been carefully designed for the SRing: isochronous mode, normal mode, and internal target mode. The isochronous mode is specially designed for in-ring high-precision mass measurements of exotic nuclei with low production cross-sections and short half-lives. The normal mode is designed to prepare high-quality Rare Isotope Beams (RIBs) for Schottky mass spectrometry experiments and in-ring atomic physics experiments. The internal target mode is designed mainly for reaction studies utilizing the gas-jet target (GJT) and specific electron target (ET). In the isochronous mode, short half-life nuclei, especially neutron-rich nuclei far away from β decay stability, can be produced by HFRS via projectile fragmentation reactions. After in-flight separation and transmission, the secondary beams are finally injected and stored in the SRing for mass and half-life measurements of exotic nuclei. For instance, measuring the masses of nuclides around

$ {}^{78} {\rm{Ni}}$ ,$ {}^{122} {\rm{Zr}}$ , and$ {}^{132} {\rm{Sn}}$ , as well as the lifetime and nuclear reaction rates of the associated nuclei, will be a crucial task for the application of isochronous mode.In the storage ring mass spectrometry, the circulating ions follow Eq. (1), which connects the revolution times (T) of the circulating ions to their mass-to-charge ratios (

$ m/q $ ) and velocities (v) [8, 9]:$ \frac{\Delta T}{T} = \frac{1}{{\gamma_{t}}^{2}}\frac{\Delta (m/q)}{m/q} + \Biggl(\frac{{\gamma}^{2}}{{\gamma_t}^{2}}-1\Biggr)\frac{\Delta v}{v}+\Biggl(\frac{{\rm d}T}{T}\Biggr)_{\rm add} ,$

(1) where γ is the relativistic Lorentz factor of the circulating ions, and

$ \gamma_t $ is the transition energy of the storage ring.$ ({\rm d}T/T)_{\rm add} $ are additional aberrations to the revolution time spread.As revealed in Eq. (1), to accurately measure the

$ m/q $ values of the circulating ions, one must measure their revolution time or frequency under the condition that the second and third terms on the right side of Eq. (1) can be reduced to a negligible value. There are two methods to reduce the influence of the second term [10]. The first method is Schottky Mass Spectrometry (SMS), which is based on the reduction of the velocity spread$ \Delta v/v $ by applying beam cooling. Beam cooling requires several seconds, which sets a limit on the half-life of the measured nuclide. This method has been employed routinely at the ESR at GSI [11−15]. Another method is Isochronous Mass Spectrometry (IMS), which is based on the isochronous setting that the$ \gamma_t $ of the storage ring is equal to γ of the nuclides of interest. In the isochronous setting, the velocity difference of the circulating ions can be compensated by the difference of their corresponding orbit lengths, giving them the same revolution times. The IMS method is ideally suited for mass measurement of very short-lived nuclides ($ \rm {\mu\text{s}} $ to$ \rm ms $ ) because one measurement takes only a few hundred microseconds. This method has been employed at both the ESR and CSRe [9, 16−19].The ions of interest are injected into the ESR or CSRe with

$ \gamma_t = \gamma = 1.41 $ or$ 1.395 $ , respectively. The achieved mass resolving powers of IMS were approximately$ R({\rm FWHM}) \leq 2\times 10^{5} $ (ESR) and$ R({\rm FWHM}) \leq 5\times 10^{5} $ (CSRe), compared to$ R({\rm FWHM}) \leq1\times 10^{6} $ obtained in SMS experiments [20, 21]. R is the mass resolving power, which is defined as follows:$ R({\rm FWHM}) = \frac {m}{\Delta m} = \frac{1}{2.355}\frac{1}{\gamma_t^{2}}\frac{T}{\sigma (T)}. $

(2) In the SRing, both the SMS and IMS are used to accurately measure the mass and half-life of the short-lived nuclei. The design goal for the SMS of the SRing is to reach a final equilibrium momentum spread at the level of

$ 2\sigma (p)/p = \pm 6\times 10^{-7} \sim 10^{-5} $ using the stochastic and electron cooling systems. Meanwhile, the design goal for the IMS of the SRing is to reach a maximum mass resolution of$ 1\times 10^{6} $ ($ {\rm FWHM} $ ) for the nuclei of interest. To achieve this, a careful design of the isochronous mode of the SRing was carried out.The paper introduces the basic isochronous mode design as well as detailed higher-order isochronous corrections of the SRing. By applying higher-order isochronous corrections, a mass resolution of

$ R({\rm FWHM}) = 1\times10^{6} $ corresponding to a relative revolution time of$ \sigma(T)/T \sim 4.9\times 10^{-7} $ is provided by the isochronous setting$ \gamma_t = 1.43 $ within the momentum acceptance of$ \pm0.2$ %. -

The mass and half-life of an atomic nucleus play an important role in nuclear structure and astrophysics, as well as in fundamental interactions and symmetries [1], which reflect all the interactions between constituent nucleons. The presently unknown nuclear masses, particularly those of nuclides far from β-stability, are required to better understand the formation of elements in the universe [2]. For instance, accurate mass values, together with other information on N = Z (A = 78−100) nuclei, are crucial for the investigation of the rp-(rapid proton capture) and αp-processes. Simultaneously, they are employed for solve many key questions related to nuclear structure, including the origin of Wigner energy, T = 0 pairing, isospin symmetry, location of proton drop lines, evolution of deformation and shell closure, testing of mass models, constraints on the B (GT) value of beta decay along N = Z, and testing of the CVC hypothesis. However, such nuclei, characterized by low production cross-sections and short half-lives, are extremely difficult to produce and measure in a laboratory. Therefore, highly efficient measurement techniques and facilities are required. Storage ring mass spectrometers offer the possibility of simultaneous mass and half-life measurements of these short-lived nuclides. There are three such heavy-ion storage rings in operation worldwide, named the experimental storage ring ESR at GSI Helmholtz Center in Darmstadt [3], experimental Cooler Storage Ring CSRe at the Institute of Modern Physics in Lanzhou [4], and Rare-RI Ring R3 at the RIKEN Nishina Center in Tokyo [5].

To extend the mass and half-life measurement program to nuclei with even smaller production rates, the Spectrometer Ring (SRing) is being designed for the next-generation High Intensity heavy-ion Accelerator Facility (HIAF), which will be located in Huizhou, China [6, 7]. The HIAF will provide a high-intensity, high-quality, and higher-energy heavy-ion beam with the synchrotron Booster Ring (BRing). The transmission line between the BRing and SRing is both a transmission line between the two rings and a high-magnetic-rigidity (25 Tm) radioactive secondary beam line HIAF FRagment Separator (HFRS). The stable nuclear heavy ion beam extracted from BRing is targeted to produce a radioactive secondary beam, which can be directly used for experimental measurement after separation and selection by HFRS, or the isolated unstable nuclear secondary beam can be injected into the SRing to prepare high-quality secondary beams for high-precision experimental measurements.

Three operation modes have been carefully designed for the SRing: isochronous mode, normal mode, and internal target mode. The isochronous mode is specially designed for in-ring high-precision mass measurements of exotic nuclei with low production cross-sections and short half-lives. The normal mode is designed to prepare high-quality Rare Isotope Beams (RIBs) for Schottky mass spectrometry experiments and in-ring atomic physics experiments. The internal target mode is designed mainly for reaction studies utilizing the gas-jet target (GJT) and specific electron target (ET). In the isochronous mode, short half-life nuclei, especially neutron-rich nuclei far away from β decay stability, can be produced by HFRS via projectile fragmentation reactions. After in-flight separation and transmission, the secondary beams are finally injected and stored in the SRing for mass and half-life measurements of exotic nuclei. For instance, measuring the masses of nuclides around

$ {}^{78} {\rm{Ni}}$ ,$ {}^{122} {\rm{Zr}}$ , and$ {}^{132} {\rm{Sn}}$ , as well as the lifetime and nuclear reaction rates of the associated nuclei, will be a crucial task for the application of isochronous mode.In the storage ring mass spectrometry, the circulating ions follow Eq. (1), which connects the revolution times (T) of the circulating ions to their mass-to-charge ratios (

$ m/q $ ) and velocities (v) [8, 9]:$ \frac{\Delta T}{T} = \frac{1}{{\gamma_{t}}^{2}}\frac{\Delta (m/q)}{m/q} + \Biggl(\frac{{\gamma}^{2}}{{\gamma_t}^{2}}-1\Biggr)\frac{\Delta v}{v}+\Biggl(\frac{{\rm d}T}{T}\Biggr)_{\rm add} ,$

(1) where γ is the relativistic Lorentz factor of the circulating ions, and

$ \gamma_t $ is the transition energy of the storage ring.$ ({\rm d}T/T)_{\rm add} $ are additional aberrations to the revolution time spread.As revealed in Eq. (1), to accurately measure the

$ m/q $ values of the circulating ions, one must measure their revolution time or frequency under the condition that the second and third terms on the right side of Eq. (1) can be reduced to a negligible value. There are two methods to reduce the influence of the second term [10]. The first method is Schottky Mass Spectrometry (SMS), which is based on the reduction of the velocity spread$ \Delta v/v $ by applying beam cooling. Beam cooling requires several seconds, which sets a limit on the half-life of the measured nuclide. This method has been employed routinely at the ESR at GSI [11−15]. Another method is Isochronous Mass Spectrometry (IMS), which is based on the isochronous setting that the$ \gamma_t $ of the storage ring is equal to γ of the nuclides of interest. In the isochronous setting, the velocity difference of the circulating ions can be compensated by the difference of their corresponding orbit lengths, giving them the same revolution times. The IMS method is ideally suited for mass measurement of very short-lived nuclides ($ \rm {\mu\text{s}} $ to$ \rm ms $ ) because one measurement takes only a few hundred microseconds. This method has been employed at both the ESR and CSRe [9, 16−19].The ions of interest are injected into the ESR or CSRe with

$ \gamma_t = \gamma = 1.41 $ or$ 1.395 $ , respectively. The achieved mass resolving powers of IMS were approximately$ R({\rm FWHM}) \leq 2\times 10^{5} $ (ESR) and$ R({\rm FWHM}) \leq 5\times 10^{5} $ (CSRe), compared to$ R({\rm FWHM}) \leq1\times 10^{6} $ obtained in SMS experiments [20, 21]. R is the mass resolving power, which is defined as follows:$ R({\rm FWHM}) = \frac {m}{\Delta m} = \frac{1}{2.355}\frac{1}{\gamma_t^{2}}\frac{T}{\sigma (T)}. $

(2) In the SRing, both the SMS and IMS are used to accurately measure the mass and half-life of the short-lived nuclei. The design goal for the SMS of the SRing is to reach a final equilibrium momentum spread at the level of

$ 2\sigma (p)/p = \pm 6\times 10^{-7} \sim 10^{-5} $ using the stochastic and electron cooling systems. Meanwhile, the design goal for the IMS of the SRing is to reach a maximum mass resolution of$ 1\times 10^{6} $ ($ {\rm FWHM} $ ) for the nuclei of interest. To achieve this, a careful design of the isochronous mode of the SRing was carried out.The paper introduces the basic isochronous mode design as well as detailed higher-order isochronous corrections of the SRing. By applying higher-order isochronous corrections, a mass resolution of

$ R({\rm FWHM}) = 1\times10^{6} $ corresponding to a relative revolution time of$ \sigma(T)/T \sim 4.9\times 10^{-7} $ is provided by the isochronous setting$ \gamma_t = 1.43 $ within the momentum acceptance of$ \pm0.2$ %. -

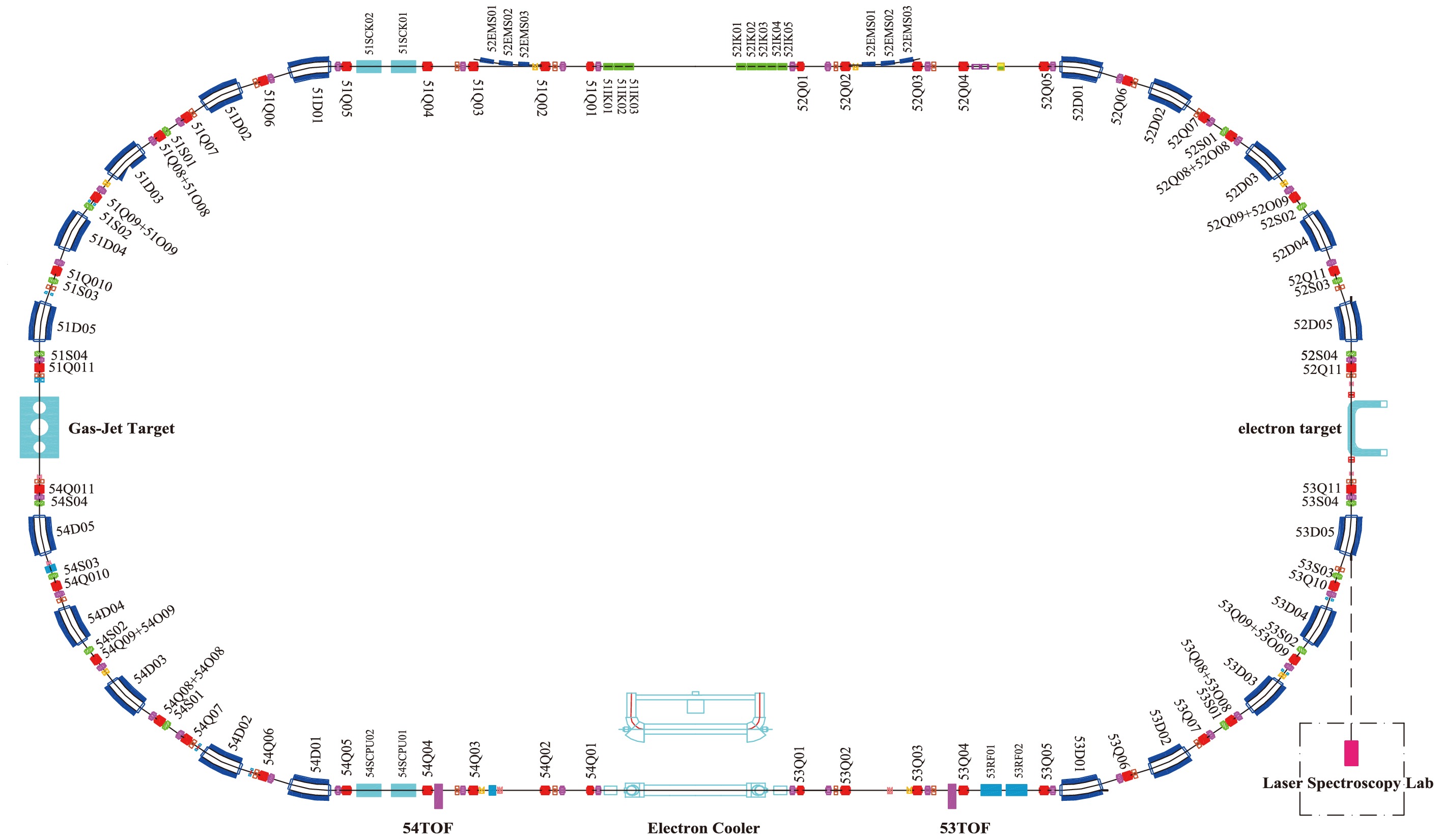

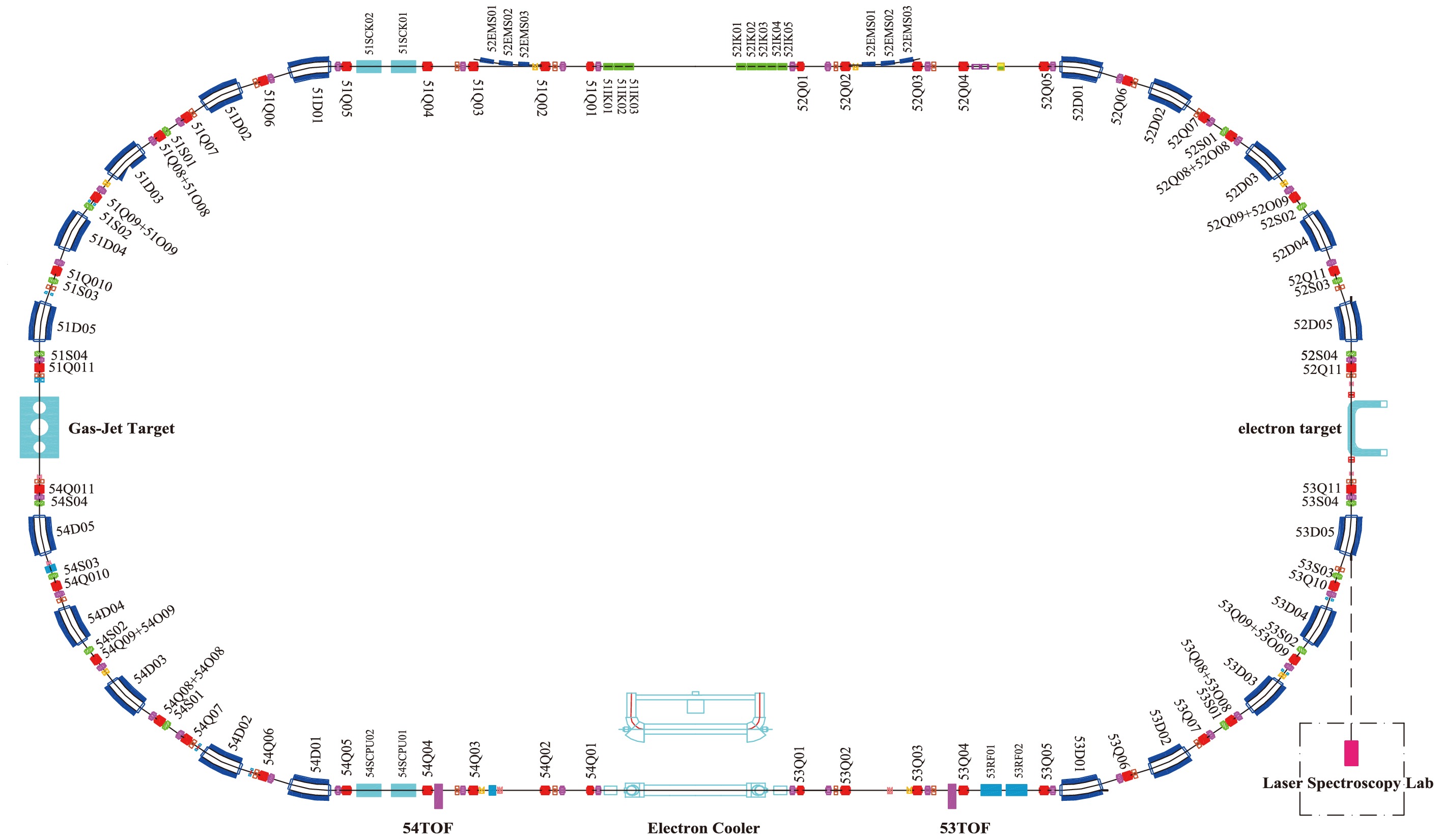

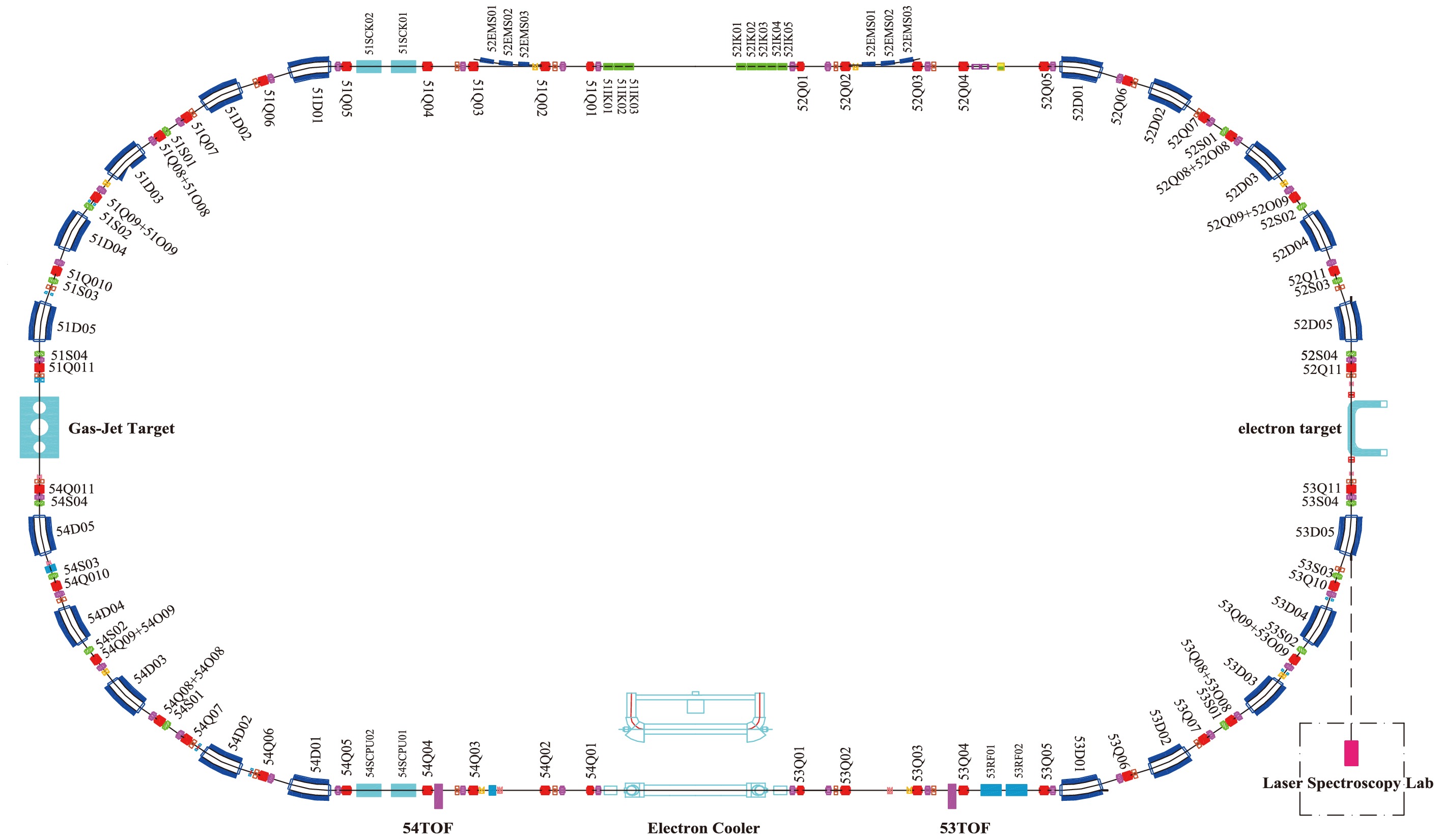

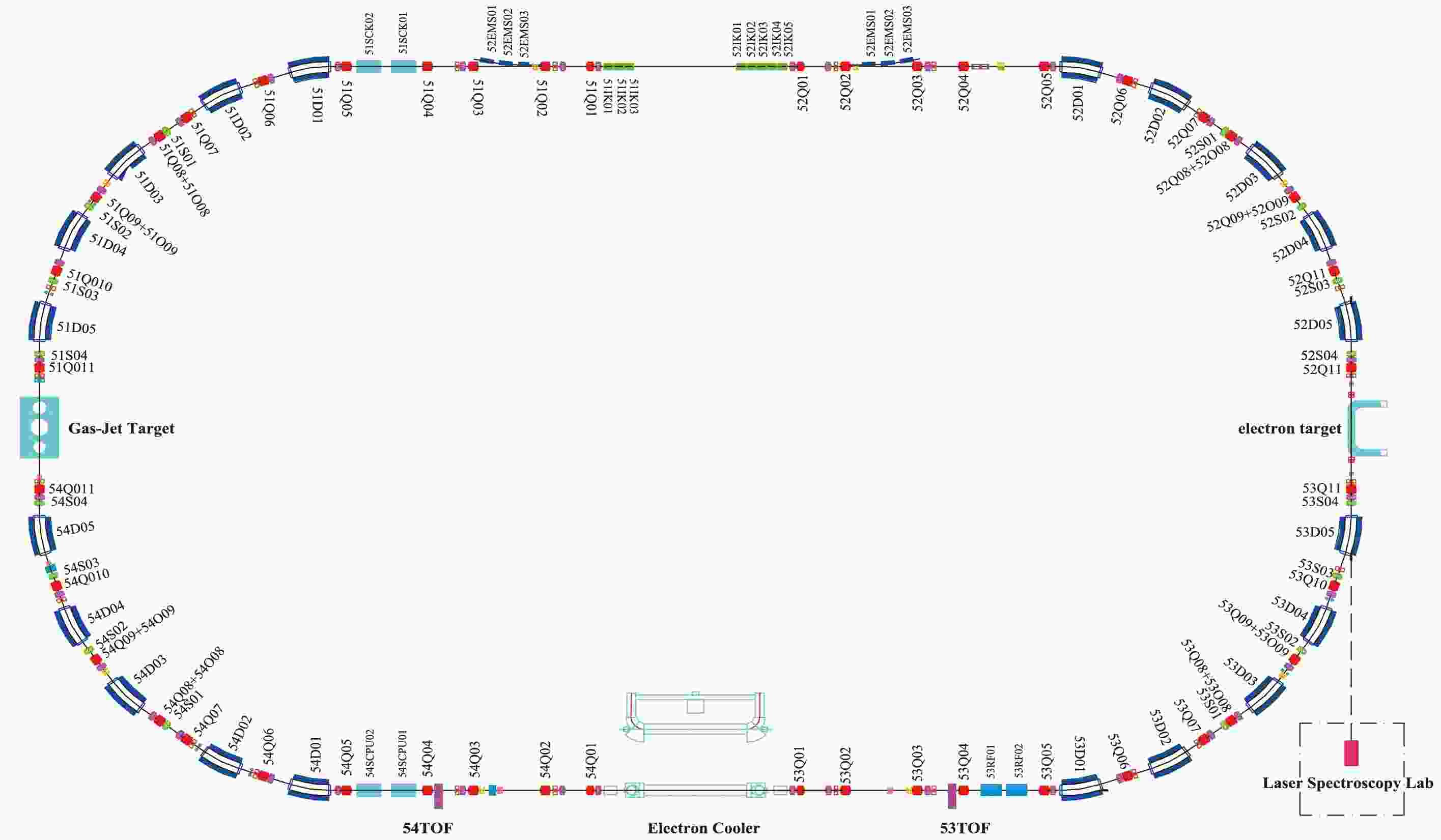

The SRing is designed as a high-precision spectrometer equipped with different detectors for nuclear and atomic physics experiments. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the SRing has a four fold symmetric structure with a total circumference of 277 meters. The designed magnetic rigidity range is 1.5−15 Tm (8−13 Tm for the isochronous mode). Each quarter of the SRing consists of 5 dipole magnets and 11 quadrupole magnets to fulfill first-order focusing conditions. The electron cooler, electron target, Gas-Jet target, and two time-of-flight (TOF) detectors will be installed in dispersion-free straight sections. The gap of dipoles is 110 mm, and the apertures of quadrupoles and sextupoles are 320 mm×140 mm. For the second-order isochronicity and chromaticity correction, 4 sextupole magnets will be installed in the arcs. Additionally, 4 octupole coils will be installed in each quarter in the arc section for higher-order nonlinear corrections.

Figure 1. (color online) Layout of the SRing lattice. The blue, red, and green squares represent the dipoles (D), quadruples (Q), octupole coils (O) and sextupoles (S) , respectively. The cyan squares represent the electron cooler, electron target, and Gas-Jet target. The purple squares represent the TOF detectors.

The SRing isochronous mode will be operated as a TOF spectrometer for short-lived exotic nuclei produced and selected in flight with the HFRS. In the isochronous setting, for definite magnetic rigidity and transition energy settings of a storage ring, only ions with certain m/q can satisfy the "isochronous condition" γ =

$ \gamma_t $ . To distinguish, these ions are called "isochronous ions". In isochronous condition, the second term on the right side of Eq. (1) can be reduced to a negligible value, and T only depends on$ m/q $ . Thus, all particles with the same$ m/q $ at different velocities travel around the ring with equal revolution times. Therefore, measurements of the revolution times give the possibility to determine$ m/q $ ratios of circulating ions.The mean transition energy

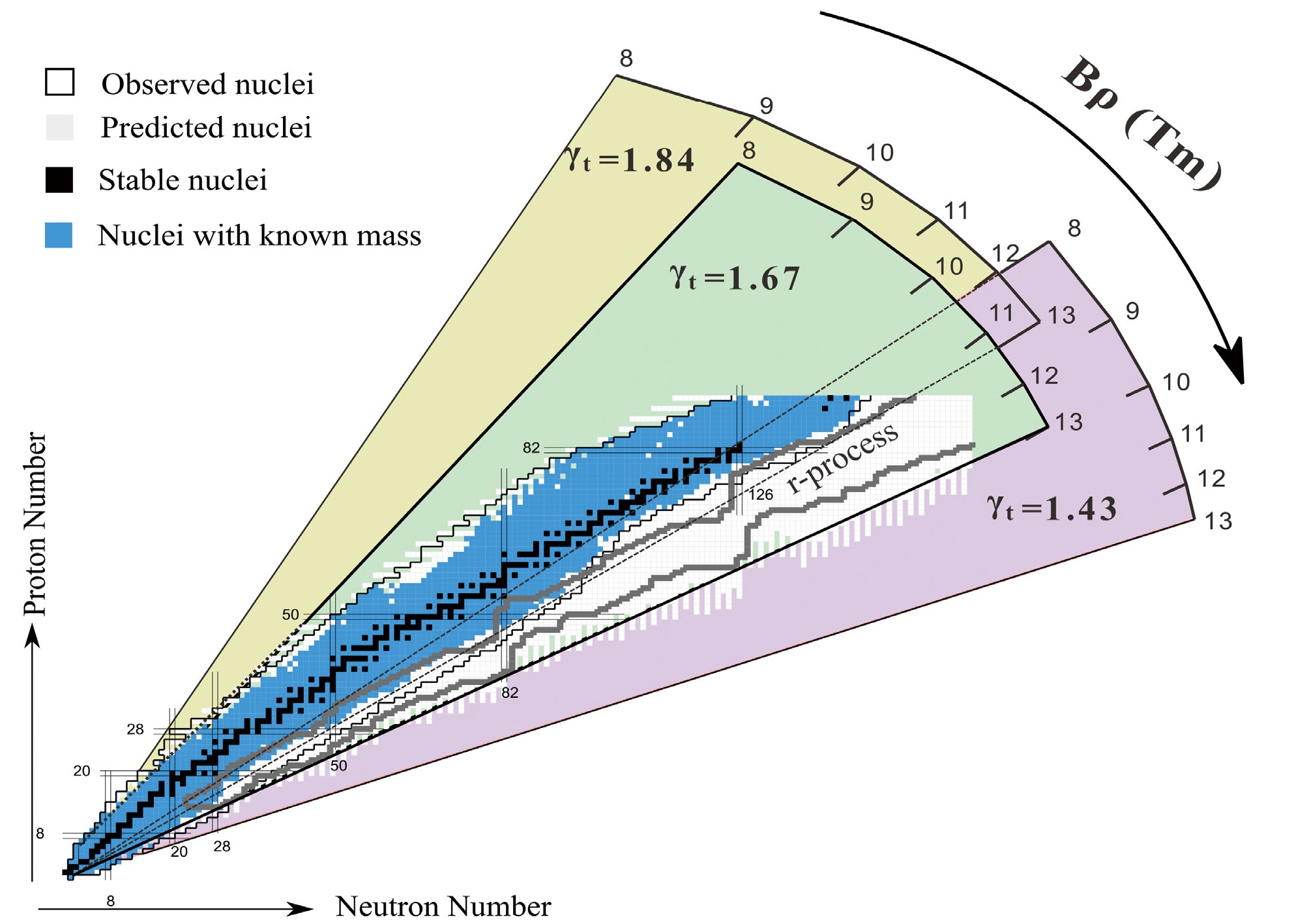

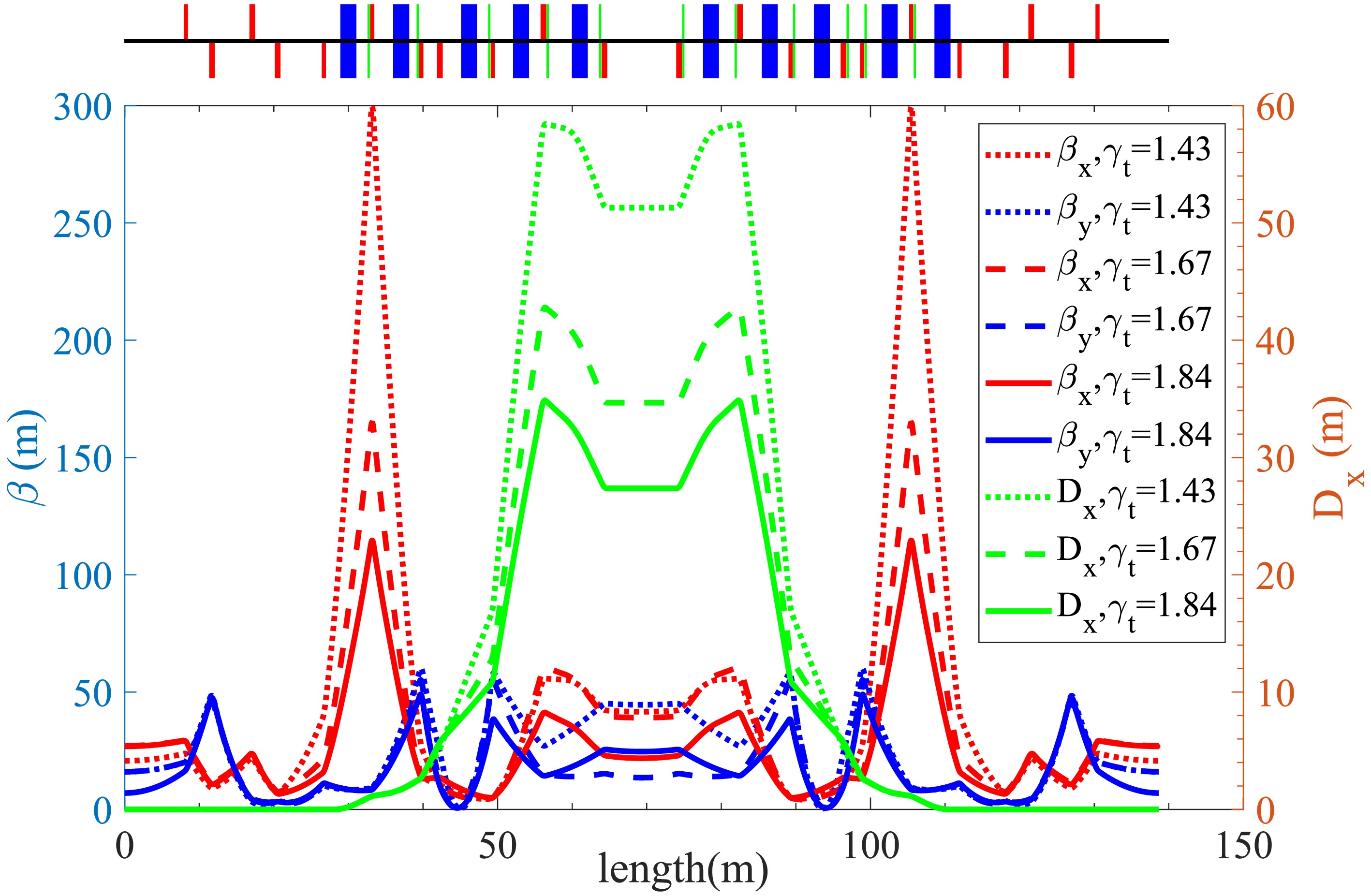

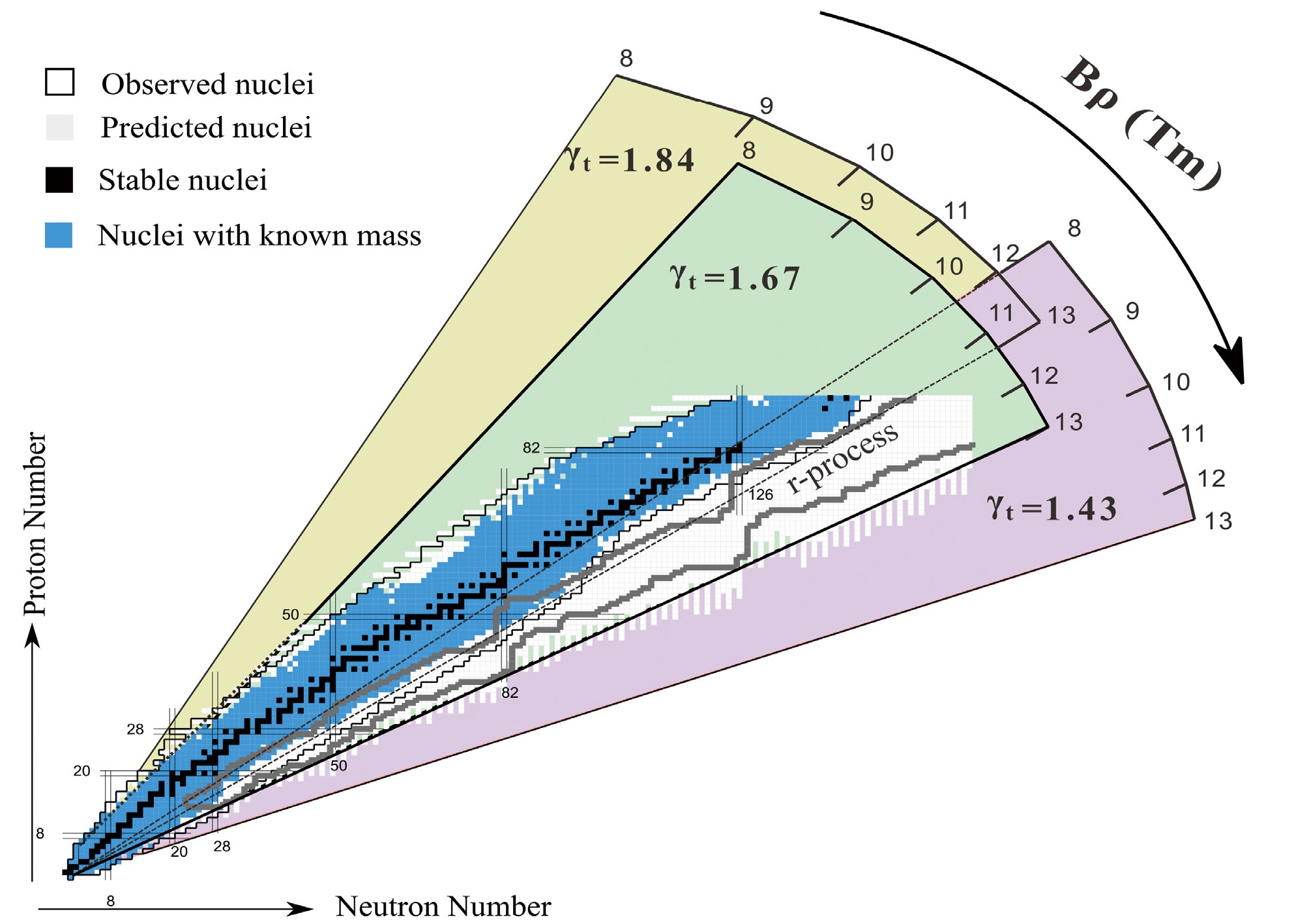

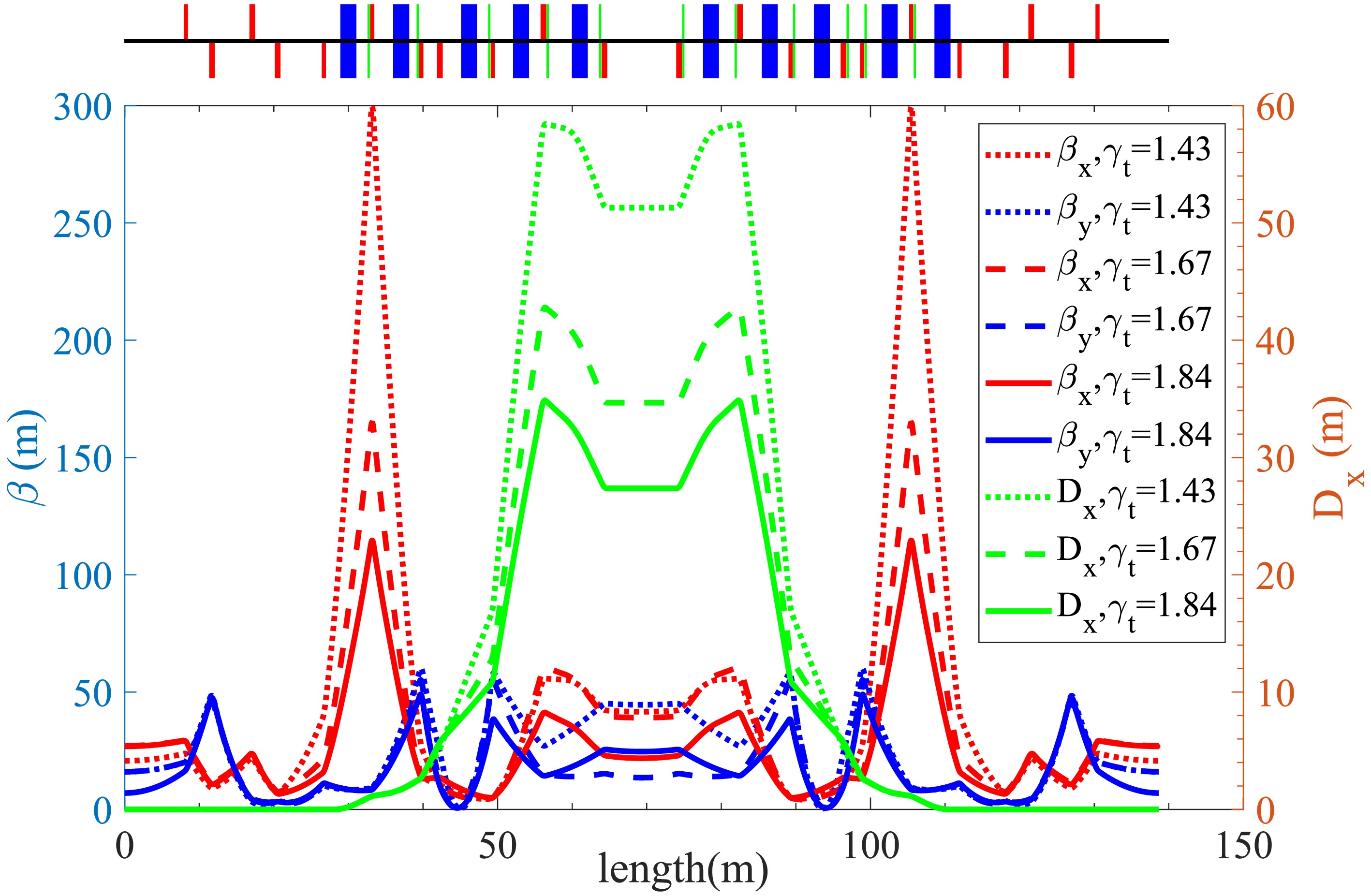

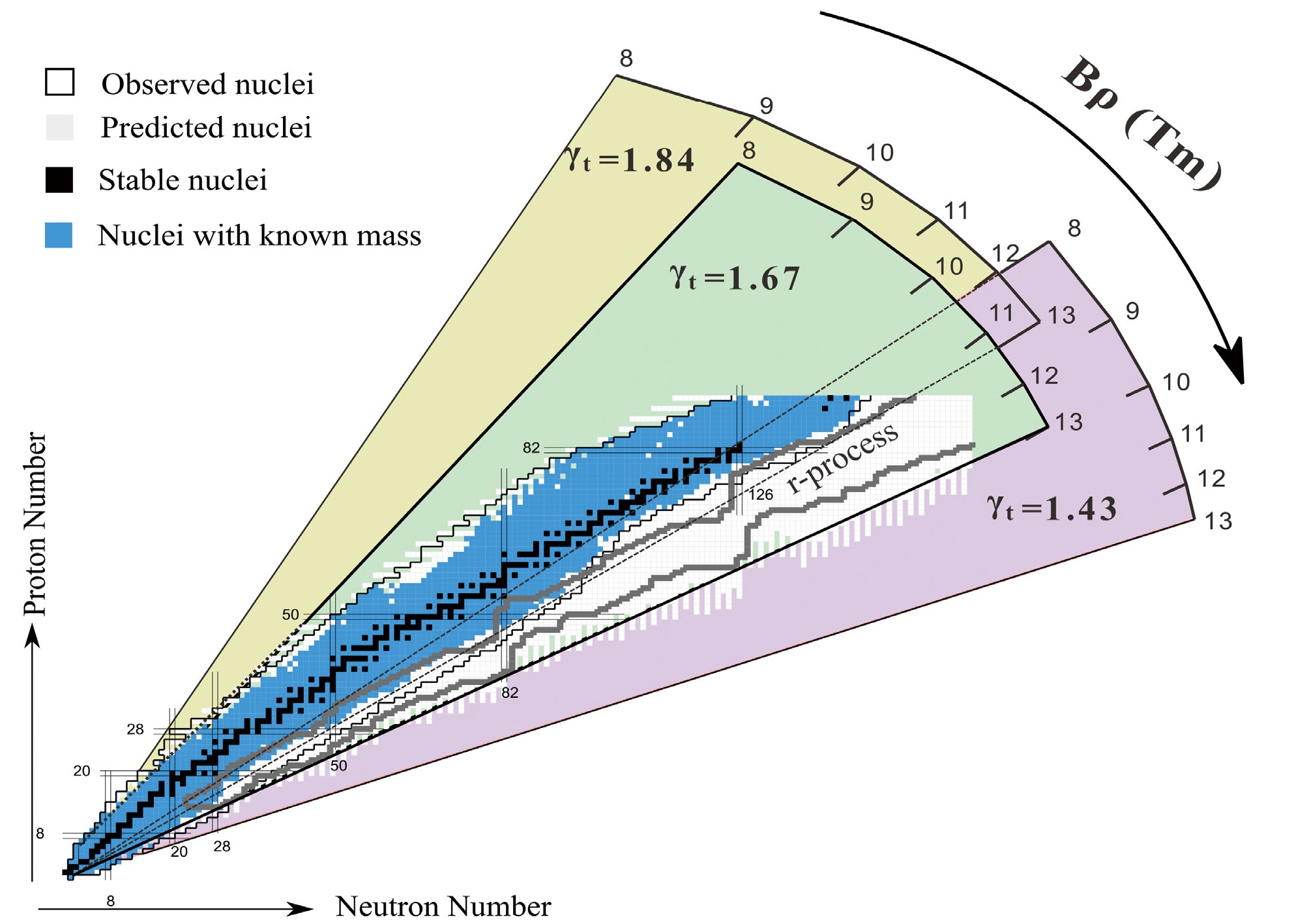

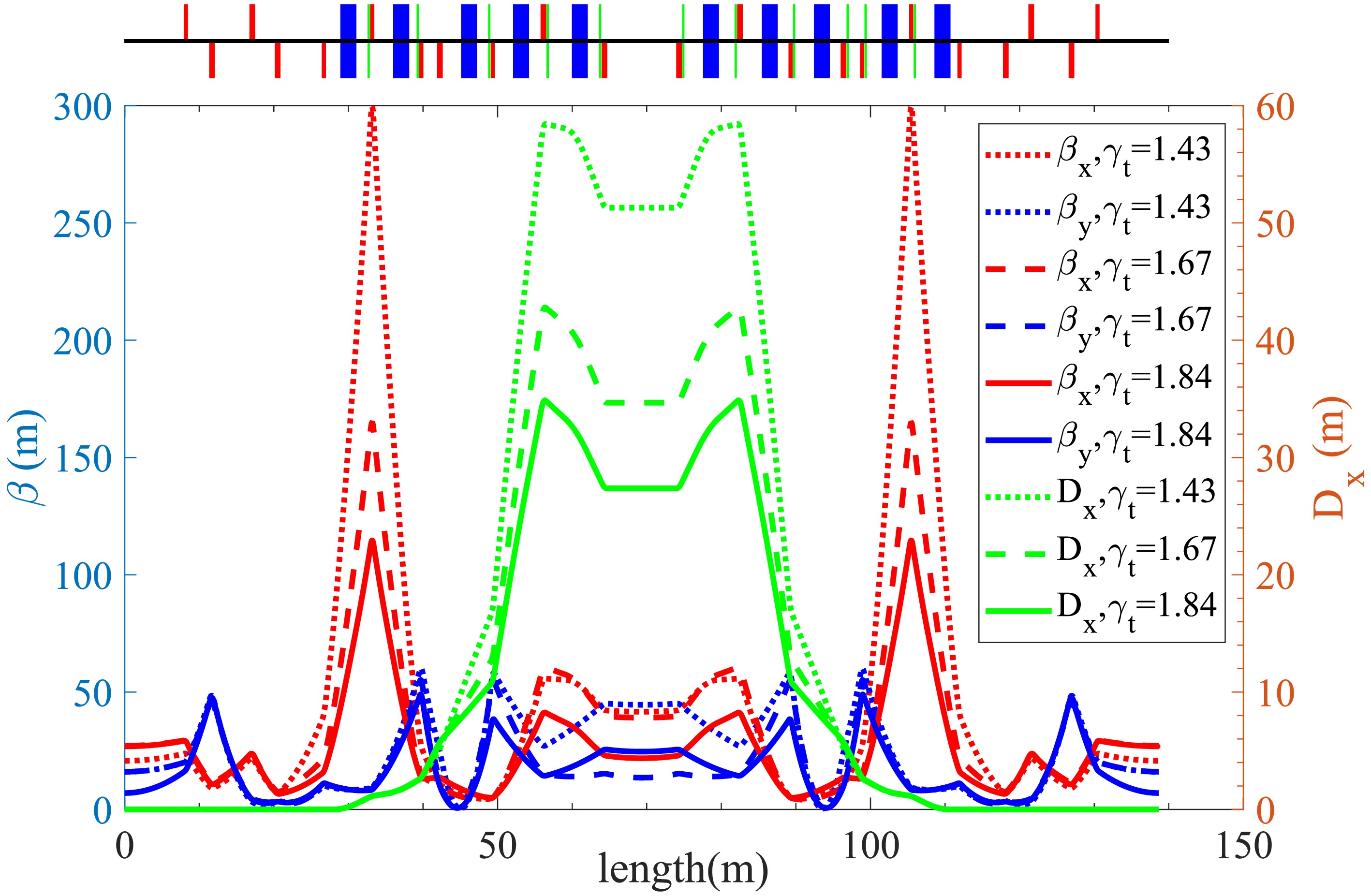

$ \gamma_t $ can be adjusted by quadrupole settings. Three settings with$ \gamma_t $ = 1.43, 1.67, and 1.84 have been designed for the IMS mode planned at the SRing. The$ \gamma_t $ = 1.43 setting is for accessing to the mass region of very neutron-rich nuclei, which allows the measurements of$ m/q $ from 2.52 to 4.10 in the magnetic rigidity region of 8−13 Tm. The$ \gamma_t $ = 1.84 setting is for accessing to very proton-rich nuclei, allowing$ m/q $ to be measure from 1.66 to 2.70 in the range of magnetic rigidity. As shown in Fig. 2, one can measure a wide region of exotic nuclei indicated in the chart of nuclei with different isochronous settings of the SRing [27]. The transverse acceptance in all three setting is 30 mm mrad in both planes. The longitudinal acceptance is smallest for the$ \gamma_t = 1.43 $ mode due to the largest dispersion and corresponds to$ \delta p/p $ =$ \pm0.2$ %. For the$ \gamma_t = $ 1.67 and 1.84 settings, the momentum acceptance is$ \pm0.25$ % and$ \pm0.3$ %, respectively. The β and dispersion functions for the three isochronous settings are shown in Fig. 3. The calculated optics parameters for different isochronous modes are given in Table 1.

Figure 2. (color online) Nuclides that could be measured in the SRing. Different sectors indicate the regions of nuclei that can be accessed with different isochronous settings and corresponding Bρ of the SRing. Known and stable nuclides are shown by black and blue, respectively [22−25]. A predicted astrophysical rapid-neutron capture process is shown as a brown curve [26].

Figure 3. (color online)

$\beta $ functions and dispersion functions along path length of half SRing for different$\gamma_t $ settings.transition energy $ \gamma_t $

1.43 1.67 1.84 $ \varepsilon_x $ /

$ {\rm mm\cdot mrad} $

30 30 30 $ \varepsilon_y $ /

$ {\rm {mm\cdot mrad}} $

30 30 30 momentum acceptance $ \pm0.2$ %

$ \pm0.25$ %

$ \pm0.30$ %

tune $ Qx/Qy $

2.46/5.44 2.58/5.56 2.65/5.62 chromaticity $ \xi_x/\xi_y $

–9.53/–3.87 –4.77/–6.57 –4.58/–7.60 Table 1. Isochronous mode optics parameters of the SRing.

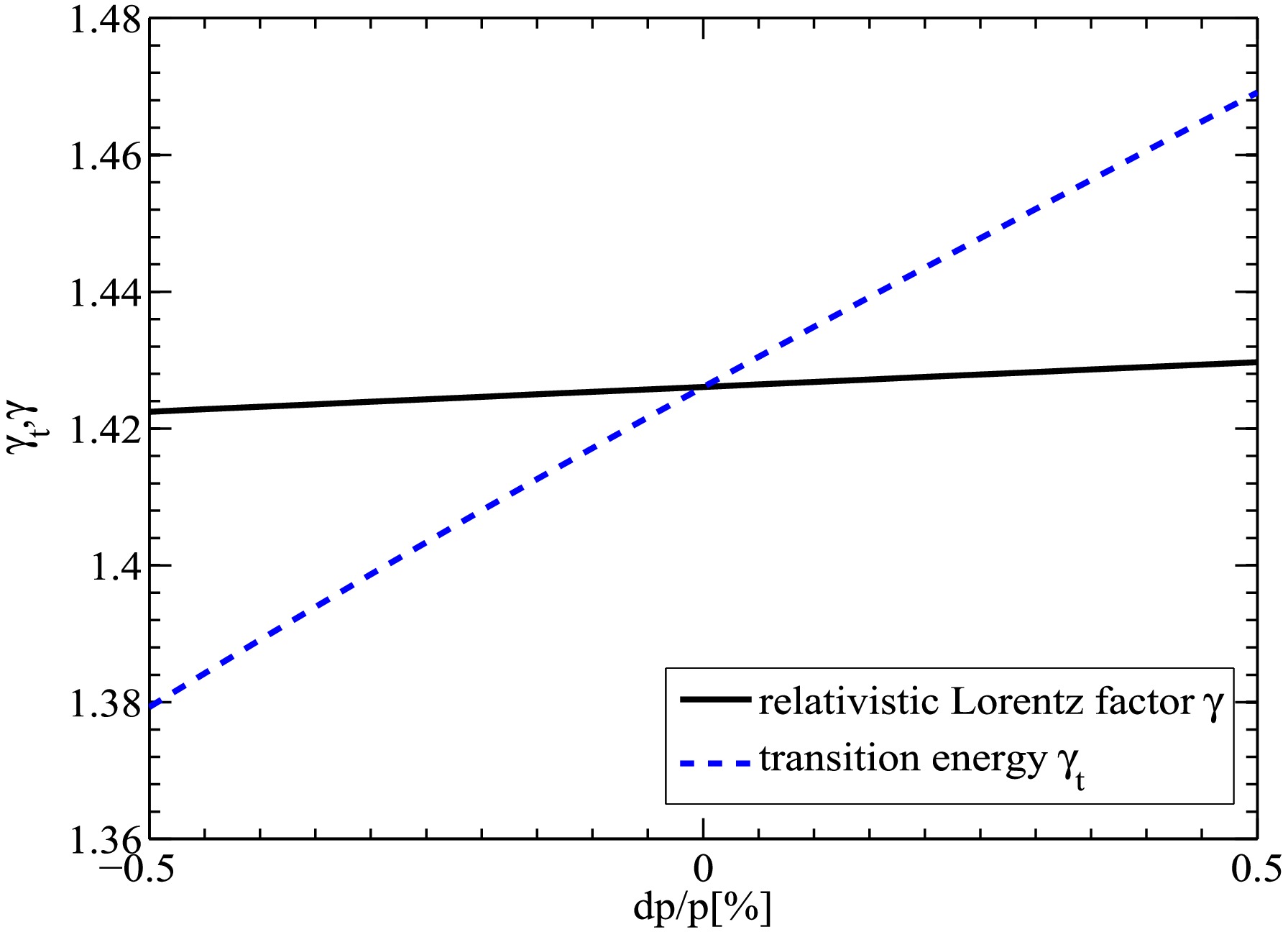

The dependence of the theoretical

$ \gamma_t $ and γ on the momentum deviation of the stored particles for the$ \gamma_t = 1.43 $ setting of the SRing was analyzed by the GICOSY code [28−30]. As shown in Fig. 4, the isochronous condition is not satisfied in the linear lattice calculations when the momentum deviation from the central momentum increases. The relative revolution time difference only reaches$ \sigma (T)/T \leq2.16\times10^{-5} $ , with a momentum deviation range of$ \pm0.2$ %. The higher-order isochronous corrections are needed to improve the revolution time resolution. -

The SRing is designed as a high-precision spectrometer equipped with different detectors for nuclear and atomic physics experiments. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the SRing has a four fold symmetric structure with a total circumference of 277 meters. The designed magnetic rigidity range is 1.5−15 Tm (8−13 Tm for the isochronous mode). Each quarter of the SRing consists of 5 dipole magnets and 11 quadrupole magnets to fulfill first-order focusing conditions. The electron cooler, electron target, Gas-Jet target, and two time-of-flight (TOF) detectors will be installed in dispersion-free straight sections. The gap of dipoles is 110 mm, and the apertures of quadrupoles and sextupoles are 320 mm×140 mm. For the second-order isochronicity and chromaticity correction, 4 sextupole magnets will be installed in the arcs. Additionally, 4 octupole coils will be installed in each quarter in the arc section for higher-order nonlinear corrections.

Figure 1. (color online) Layout of the SRing lattice. The blue, red, and green squares represent the dipoles (D), quadruples (Q), octupole coils (O) and sextupoles (S) , respectively. The cyan squares represent the electron cooler, electron target, and Gas-Jet target. The purple squares represent the TOF detectors.

The SRing isochronous mode will be operated as a TOF spectrometer for short-lived exotic nuclei produced and selected in flight with the HFRS. In the isochronous setting, for definite magnetic rigidity and transition energy settings of a storage ring, only ions with certain m/q can satisfy the "isochronous condition" γ =

$ \gamma_t $ . To distinguish, these ions are called "isochronous ions". In isochronous condition, the second term on the right side of Eq. (1) can be reduced to a negligible value, and T only depends on$ m/q $ . Thus, all particles with the same$ m/q $ at different velocities travel around the ring with equal revolution times. Therefore, measurements of the revolution times give the possibility to determine$ m/q $ ratios of circulating ions.The mean transition energy

$ \gamma_t $ can be adjusted by quadrupole settings. Three settings with$ \gamma_t $ = 1.43, 1.67, and 1.84 have been designed for the IMS mode planned at the SRing. The$ \gamma_t $ = 1.43 setting is for accessing to the mass region of very neutron-rich nuclei, which allows the measurements of$ m/q $ from 2.52 to 4.10 in the magnetic rigidity region of 8−13 Tm. The$ \gamma_t $ = 1.84 setting is for accessing to very proton-rich nuclei, allowing$ m/q $ to be measure from 1.66 to 2.70 in the range of magnetic rigidity. As shown in Fig. 2, one can measure a wide region of exotic nuclei indicated in the chart of nuclei with different isochronous settings of the SRing [27]. The transverse acceptance in all three setting is 30 mm mrad in both planes. The longitudinal acceptance is smallest for the$ \gamma_t = 1.43 $ mode due to the largest dispersion and corresponds to$ \delta p/p $ =$ \pm0.2$ %. For the$ \gamma_t = $ 1.67 and 1.84 settings, the momentum acceptance is$ \pm0.25$ % and$ \pm0.3$ %, respectively. The β and dispersion functions for the three isochronous settings are shown in Fig. 3. The calculated optics parameters for different isochronous modes are given in Table 1.

Figure 2. (color online) Nuclides that could be measured in the SRing. Different sectors indicate the regions of nuclei that can be accessed with different isochronous settings and corresponding Bρ of the SRing. Known and stable nuclides are shown by black and blue, respectively [22−25]. A predicted astrophysical rapid-neutron capture process is shown as a brown curve [26].

Figure 3. (color online)

$\beta $ functions and dispersion functions along path length of half SRing for different$\gamma_t $ settings.transition energy $ \gamma_t $

1.43 1.67 1.84 $ \varepsilon_x $ /

$ {\rm mm\cdot mrad} $

30 30 30 $ \varepsilon_y $ /

$ {\rm {mm\cdot mrad}} $

30 30 30 momentum acceptance $ \pm0.2$ %

$ \pm0.25$ %

$ \pm0.30$ %

tune $ Qx/Qy $

2.46/5.44 2.58/5.56 2.65/5.62 chromaticity $ \xi_x/\xi_y $

–9.53/–3.87 –4.77/–6.57 –4.58/–7.60 Table 1. Isochronous mode optics parameters of the SRing.

The dependence of the theoretical

$ \gamma_t $ and γ on the momentum deviation of the stored particles for the$ \gamma_t = 1.43 $ setting of the SRing was analyzed by the GICOSY code [28−30]. As shown in Fig. 4, the isochronous condition is not satisfied in the linear lattice calculations when the momentum deviation from the central momentum increases. The relative revolution time difference only reaches$ \sigma (T)/T \leq2.16\times10^{-5} $ , with a momentum deviation range of$ \pm0.2$ %. The higher-order isochronous corrections are needed to improve the revolution time resolution. -

The SRing is designed as a high-precision spectrometer equipped with different detectors for nuclear and atomic physics experiments. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the SRing has a four fold symmetric structure with a total circumference of 277 meters. The designed magnetic rigidity range is 1.5−15 Tm (8−13 Tm for the isochronous mode). Each quarter of the SRing consists of 5 dipole magnets and 11 quadrupole magnets to fulfill first-order focusing conditions. The electron cooler, electron target, Gas-Jet target, and two time-of-flight (TOF) detectors will be installed in dispersion-free straight sections. The gap of dipoles is 110 mm, and the apertures of quadrupoles and sextupoles are 320 mm×140 mm. For the second-order isochronicity and chromaticity correction, 4 sextupole magnets will be installed in the arcs. Additionally, 4 octupole coils will be installed in each quarter in the arc section for higher-order nonlinear corrections.

Figure 1. (color online) Layout of the SRing lattice. The blue, red, and green squares represent the dipoles (D), quadruples (Q), octupole coils (O) and sextupoles (S) , respectively. The cyan squares represent the electron cooler, electron target, and Gas-Jet target. The purple squares represent the TOF detectors.

The SRing isochronous mode will be operated as a TOF spectrometer for short-lived exotic nuclei produced and selected in flight with the HFRS. In the isochronous setting, for definite magnetic rigidity and transition energy settings of a storage ring, only ions with certain m/q can satisfy the "isochronous condition" γ =

$ \gamma_t $ . To distinguish, these ions are called "isochronous ions". In isochronous condition, the second term on the right side of Eq. (1) can be reduced to a negligible value, and T only depends on$ m/q $ . Thus, all particles with the same$ m/q $ at different velocities travel around the ring with equal revolution times. Therefore, measurements of the revolution times give the possibility to determine$ m/q $ ratios of circulating ions.The mean transition energy

$ \gamma_t $ can be adjusted by quadrupole settings. Three settings with$ \gamma_t $ = 1.43, 1.67, and 1.84 have been designed for the IMS mode planned at the SRing. The$ \gamma_t $ = 1.43 setting is for accessing to the mass region of very neutron-rich nuclei, which allows the measurements of$ m/q $ from 2.52 to 4.10 in the magnetic rigidity region of 8−13 Tm. The$ \gamma_t $ = 1.84 setting is for accessing to very proton-rich nuclei, allowing$ m/q $ to be measure from 1.66 to 2.70 in the range of magnetic rigidity. As shown in Fig. 2, one can measure a wide region of exotic nuclei indicated in the chart of nuclei with different isochronous settings of the SRing [27]. The transverse acceptance in all three setting is 30 mm mrad in both planes. The longitudinal acceptance is smallest for the$ \gamma_t = 1.43 $ mode due to the largest dispersion and corresponds to$ \delta p/p $ =$ \pm0.2$ %. For the$ \gamma_t = $ 1.67 and 1.84 settings, the momentum acceptance is$ \pm0.25$ % and$ \pm0.3$ %, respectively. The β and dispersion functions for the three isochronous settings are shown in Fig. 3. The calculated optics parameters for different isochronous modes are given in Table 1.

Figure 2. (color online) Nuclides that could be measured in the SRing. Different sectors indicate the regions of nuclei that can be accessed with different isochronous settings and corresponding Bρ of the SRing. Known and stable nuclides are shown by black and blue, respectively [22−25]. A predicted astrophysical rapid-neutron capture process is shown as a brown curve [26].

Figure 3. (color online)

$\beta $ functions and dispersion functions along path length of half SRing for different$\gamma_t $ settings.transition energy $ \gamma_t $

1.43 1.67 1.84 $ \varepsilon_x $ /

$ {\rm mm\cdot mrad} $

30 30 30 $ \varepsilon_y $ /

$ {\rm {mm\cdot mrad}} $

30 30 30 momentum acceptance $ \pm0.2$ %

$ \pm0.25$ %

$ \pm0.30$ %

tune $ Qx/Qy $

2.46/5.44 2.58/5.56 2.65/5.62 chromaticity $ \xi_x/\xi_y $

–9.53/–3.87 –4.77/–6.57 –4.58/–7.60 Table 1. Isochronous mode optics parameters of the SRing.

The dependence of the theoretical

$ \gamma_t $ and γ on the momentum deviation of the stored particles for the$ \gamma_t = 1.43 $ setting of the SRing was analyzed by the GICOSY code [28−30]. As shown in Fig. 4, the isochronous condition is not satisfied in the linear lattice calculations when the momentum deviation from the central momentum increases. The relative revolution time difference only reaches$ \sigma (T)/T \leq2.16\times10^{-5} $ , with a momentum deviation range of$ \pm0.2$ %. The higher-order isochronous corrections are needed to improve the revolution time resolution. -

The relative revolution time difference between an arbitrary and the reference particle can be expressed as a higher-order approximation using a Taylor series in terms of the initial coordinates [31, 32]:

$ \begin{aligned}[b] \Delta T/T =\;& (t|x)_c x+(t|a)_c a+(t|\delta)_c \delta \\&+(t|xx)_c x^{2}+(t|xa)_c xa+(t|aa)_c a^{2}+(t|yy)_c y^{2}\\&+(t|yb)_c yb+(t|bb)_c b^{2} \\&+(t|x\delta)_c x\delta+(t|a\delta)_c a\delta+(t|\delta\delta)_c \delta^{2} \\&+(t|xxx)_c x^{3}+\cdots +(t|\delta\delta\delta)_c \delta^{3} \\&+\cdots \end{aligned} $

(3) The coefficients of the Taylor series are the partial derivatives of the left coordinate before the line with respect to the right coordinates, as well as the transfer matrix elements, e.g.,

$ t(x\delta)= \frac{\partial^2 t}{\partial x\partial\delta}$ , x and y are the transverse positions, a and b are the transverse slopes, and δ is the relative momentum deviation$ (\delta = (p-p_0)/p_0) $ to the reference particle. c represents coefficients normalized by the total time of flight$ nT_0 $ ($ (t|x)_c = (t|x)/nT_0 $ ), where n is the number of turns and$ T_0 $ is the revolution time of the reference particle.The terms in Eq. (3) covers the contributions from linear lattice unisochroneity as shown in Fig. 4, as well as the third term

$ $ $({\rm d}T/T)_{\rm add} $ on the right side of Eq. (1) [32, 33]. These aberrations include the influence of momentum deviation, transverse emittance and nonlinear field errors, etc [34−37]. The aberrations are corrected with two tricks. In the first trick, the influence of transverse emittance is investigated corrected by using sextupoles in the dispersive section. This trick tries to minimize the width of$\gamma_t $ curve in Fig. 4 without considering of its shape. The second trick will focusing on investigation the shapes of$\gamma_t $ curve with influence of field imperfections in addition to the unisochroneity of linear lattice shown in Fig. 4, and correction of the$\gamma_t $ curve to satisfy isochronous condition. -

The relative revolution time difference between an arbitrary and the reference particle can be expressed as a higher-order approximation using a Taylor series in terms of the initial coordinates [31, 32]:

$ \begin{aligned}[b] \Delta T/T =\;& (t|x)_c x+(t|a)_c a+(t|\delta)_c \delta \\&+(t|xx)_c x^{2}+(t|xa)_c xa+(t|aa)_c a^{2}+(t|yy)_c y^{2}\\&+(t|yb)_c yb+(t|bb)_c b^{2} \\&+(t|x\delta)_c x\delta+(t|a\delta)_c a\delta+(t|\delta\delta)_c \delta^{2} \\&+(t|xxx)_c x^{3}+\cdots +(t|\delta\delta\delta)_c \delta^{3} \\&+\cdots \end{aligned} $

(3) The coefficients of the Taylor series are the partial derivatives of the left coordinate before the line with respect to the right coordinates, as well as the transfer matrix elements, e.g.,

$ t(x\delta)= \frac{\partial^2 t}{\partial x\partial\delta}$ , x and y are the transverse positions, a and b are the transverse slopes, and δ is the relative momentum deviation$ (\delta = (p-p_0)/p_0) $ to the reference particle. c represents coefficients normalized by the total time of flight$ nT_0 $ ($ (t|x)_c = (t|x)/nT_0 $ ), where n is the number of turns and$ T_0 $ is the revolution time of the reference particle.The terms in Eq. (3) covers the contributions from linear lattice unisochroneity as shown in Fig. 4, as well as the third term

$ $ $({\rm d}T/T)_{\rm add} $ on the right side of Eq. (1) [32, 33]. These aberrations include the influence of momentum deviation, transverse emittance and nonlinear field errors, etc [34−37]. The aberrations are corrected with two tricks. In the first trick, the influence of transverse emittance is investigated corrected by using sextupoles in the dispersive section. This trick tries to minimize the width of$\gamma_t $ curve in Fig. 4 without considering of its shape. The second trick will focusing on investigation the shapes of$\gamma_t $ curve with influence of field imperfections in addition to the unisochroneity of linear lattice shown in Fig. 4, and correction of the$\gamma_t $ curve to satisfy isochronous condition. -

The relative revolution time difference between an arbitrary and the reference particle can be expressed as a higher-order approximation using a Taylor series in terms of the initial coordinates [31, 32]:

$ \begin{aligned}[b] \Delta T/T =\;& (t|x)_c x+(t|a)_c a+(t|\delta)_c \delta \\&+(t|xx)_c x^{2}+(t|xa)_c xa+(t|aa)_c a^{2}+(t|yy)_c y^{2}\\&+(t|yb)_c yb+(t|bb)_c b^{2} \\&+(t|x\delta)_c x\delta+(t|a\delta)_c a\delta+(t|\delta\delta)_c \delta^{2} \\&+(t|xxx)_c x^{3}+\cdots +(t|\delta\delta\delta)_c \delta^{3} \\&+\cdots \end{aligned} $

(3) The coefficients of the Taylor series are the partial derivatives of the left coordinate before the line with respect to the right coordinates, as well as the transfer matrix elements, e.g.,

$ t(x\delta)= \frac{\partial^2 t}{\partial x\partial\delta}$ , x and y are the transverse positions, a and b are the transverse slopes, and δ is the relative momentum deviation$ (\delta = (p-p_0)/p_0) $ to the reference particle. c represents coefficients normalized by the total time of flight$ nT_0 $ ($ (t|x)_c = (t|x)/nT_0 $ ), where n is the number of turns and$ T_0 $ is the revolution time of the reference particle.The terms in Eq. (3) covers the contributions from linear lattice unisochroneity as shown in Fig. 4, as well as the third term

$ $ $({\rm d}T/T)_{\rm add} $ on the right side of Eq. (1) [32, 33]. These aberrations include the influence of momentum deviation, transverse emittance and nonlinear field errors, etc [34−37]. The aberrations are corrected with two tricks. In the first trick, the influence of transverse emittance is investigated corrected by using sextupoles in the dispersive section. This trick tries to minimize the width of$\gamma_t $ curve in Fig. 4 without considering of its shape. The second trick will focusing on investigation the shapes of$\gamma_t $ curve with influence of field imperfections in addition to the unisochroneity of linear lattice shown in Fig. 4, and correction of the$\gamma_t $ curve to satisfy isochronous condition. -

For ions with the same momentum in the storage ring, their orbital length deviation and consequently the relative revolution time difference depends quadratically on the amplitude of the betatron oscillations, which is directly related to the transverse emittance as follow [33, 38]:

$ \Biggl(\frac{\Delta L}{L}\Biggr)_{\beta}\approx\frac {1}{4L_0}\int_0^{s}(\varepsilon_x \gamma_x(s) +\varepsilon_x h^{2}(s)\beta_x(s) +\varepsilon_y \gamma_y(s)){\rm d}s ,$

(4) where

$ \varepsilon_x $ and$ \varepsilon_y $ are the transverse emittance values in each plane.$ \beta_x(s) $ ,$ \gamma_x(s) $ , and$ \gamma_y(s) $ are the Twiss parameters of the storage ring.$ h(s)=\frac{1}{\rho(s)} $ is the bending power of the dipole field.When the transverse emittance increases, ions oscillate around the reference orbit with higher betatron oscillation amplitude. Then, they will have longer orbit length and revolution time. Large acceptance of the SRing is more crucial for IMS experiments of very short-lived nuclei with low production cross-sections. This means a high transmission efficiency from the HFRS to the SRing is desired, and the stored ions may have a large momentum spread and large transverse emittance. To increase the mass resolving power while keeping large acceptance of the SRing, the influence of transverse emittance on the revolution time spread should be reduced by using the sextupoles in the dispersion section of the SRing.

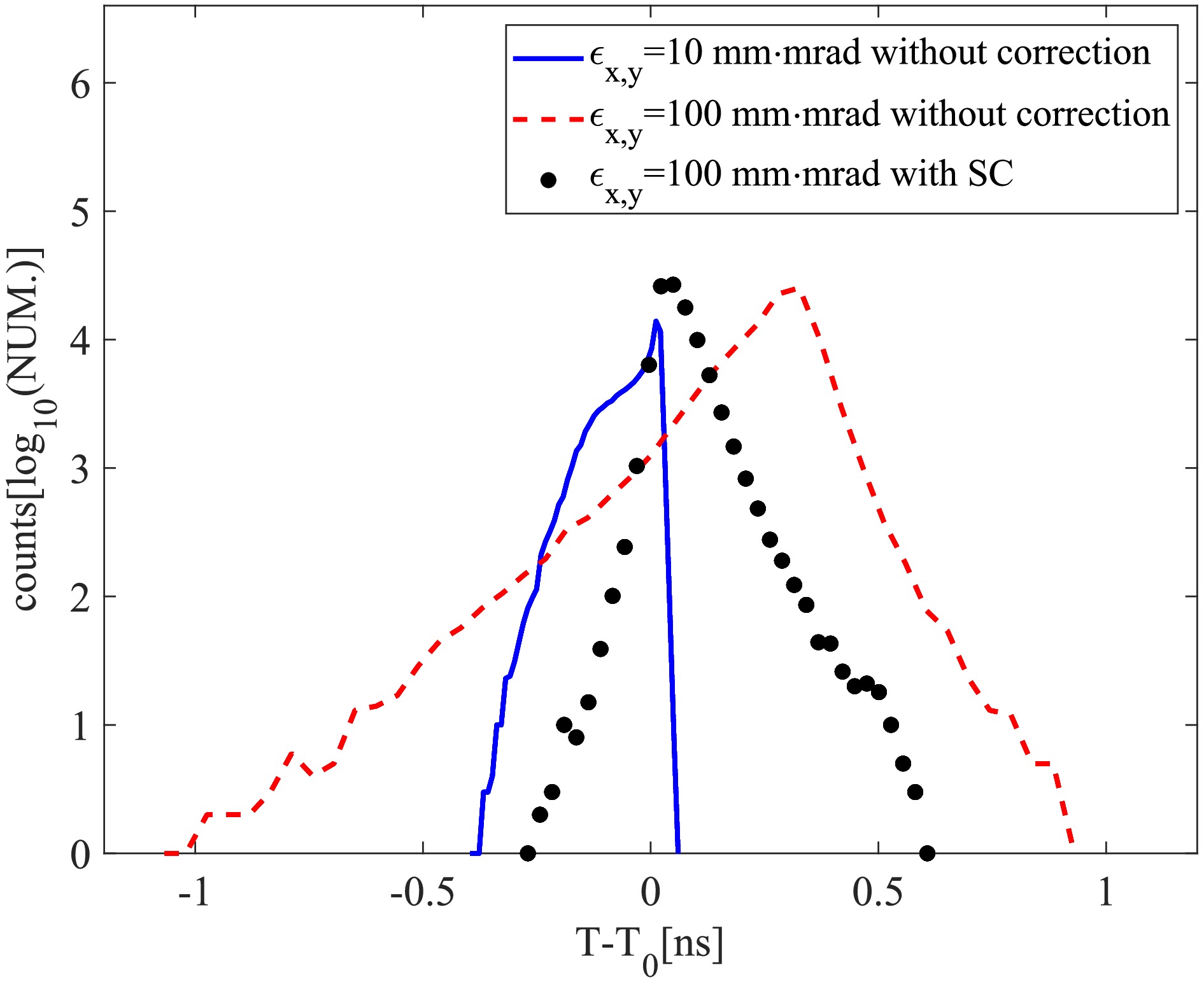

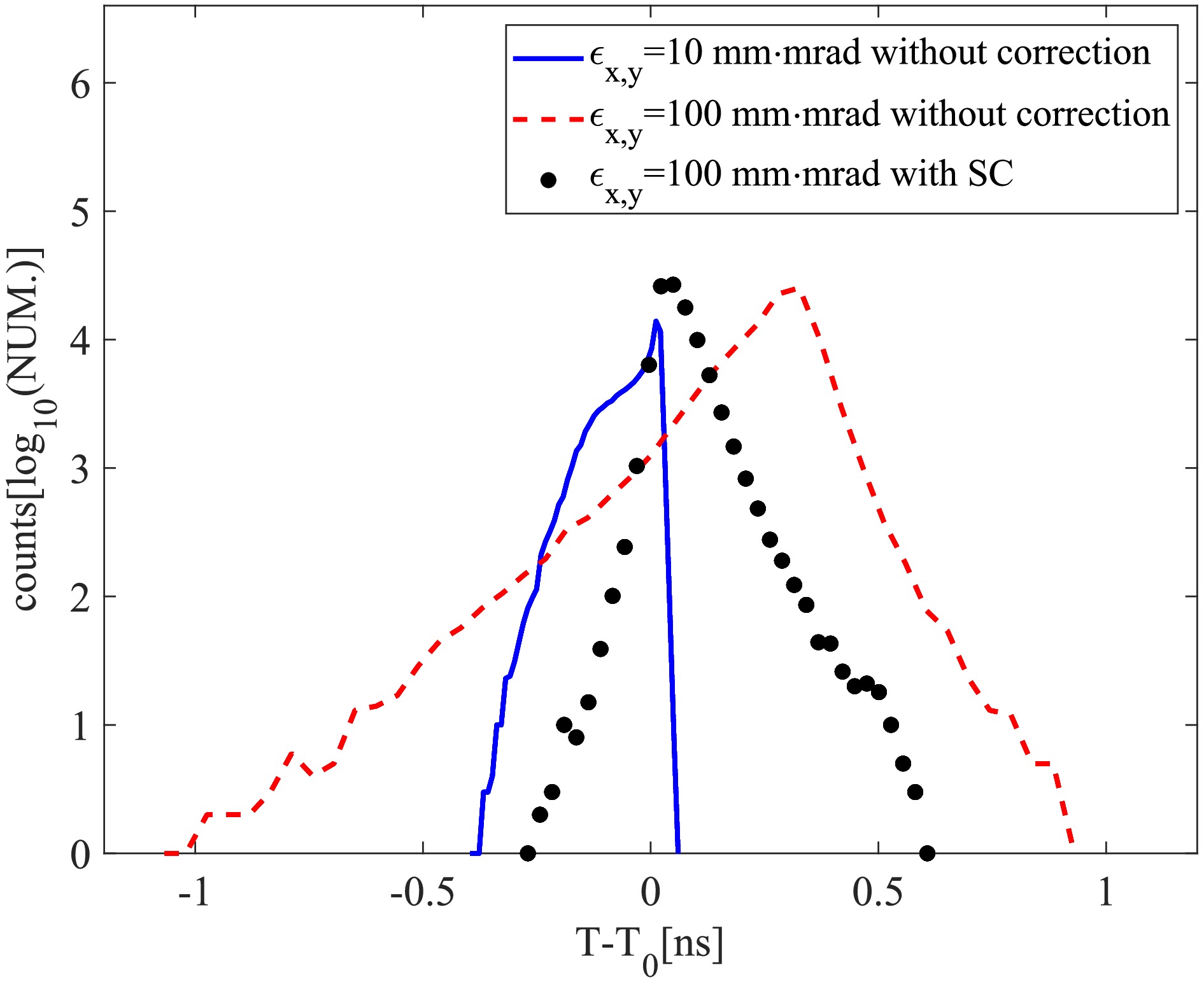

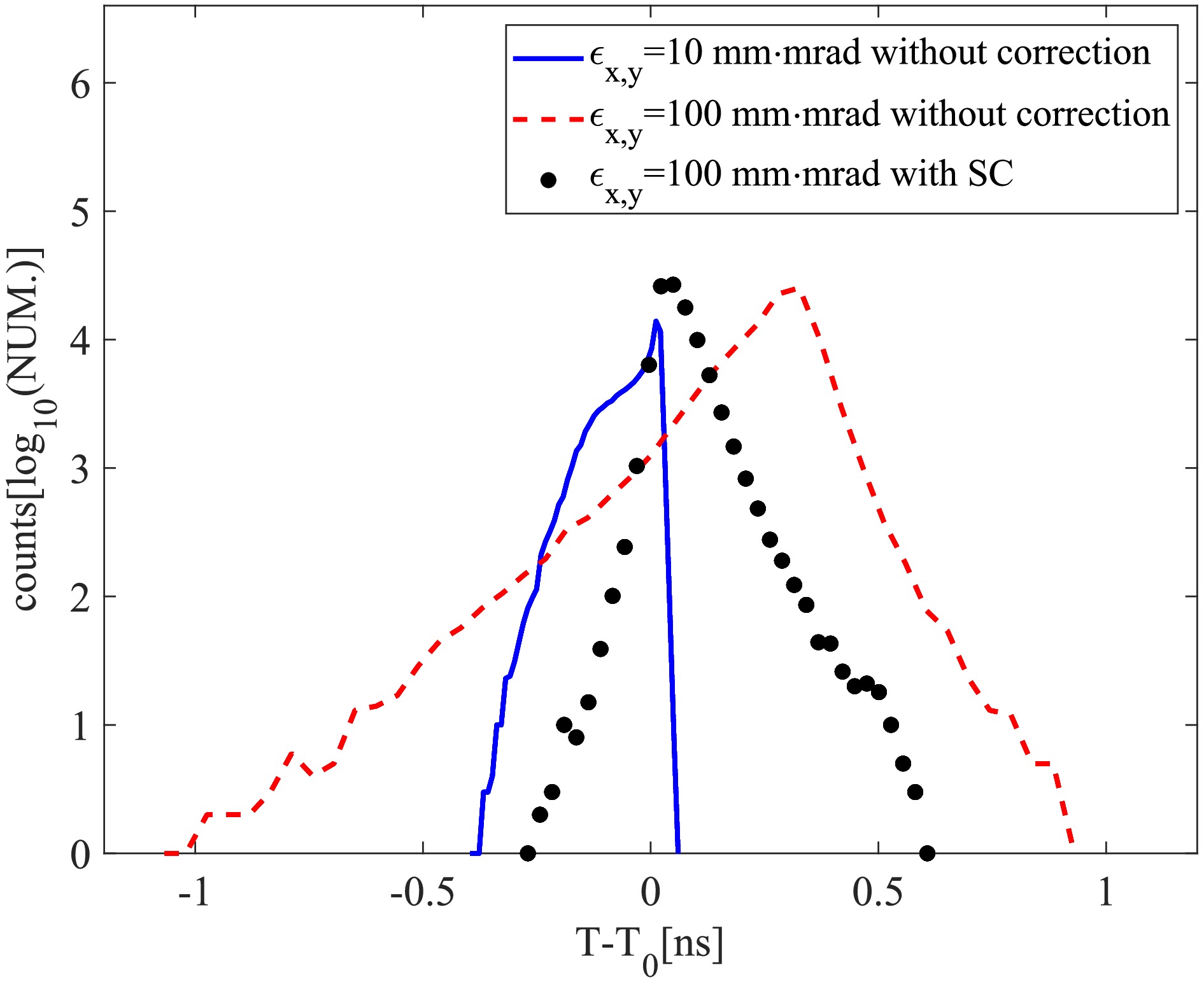

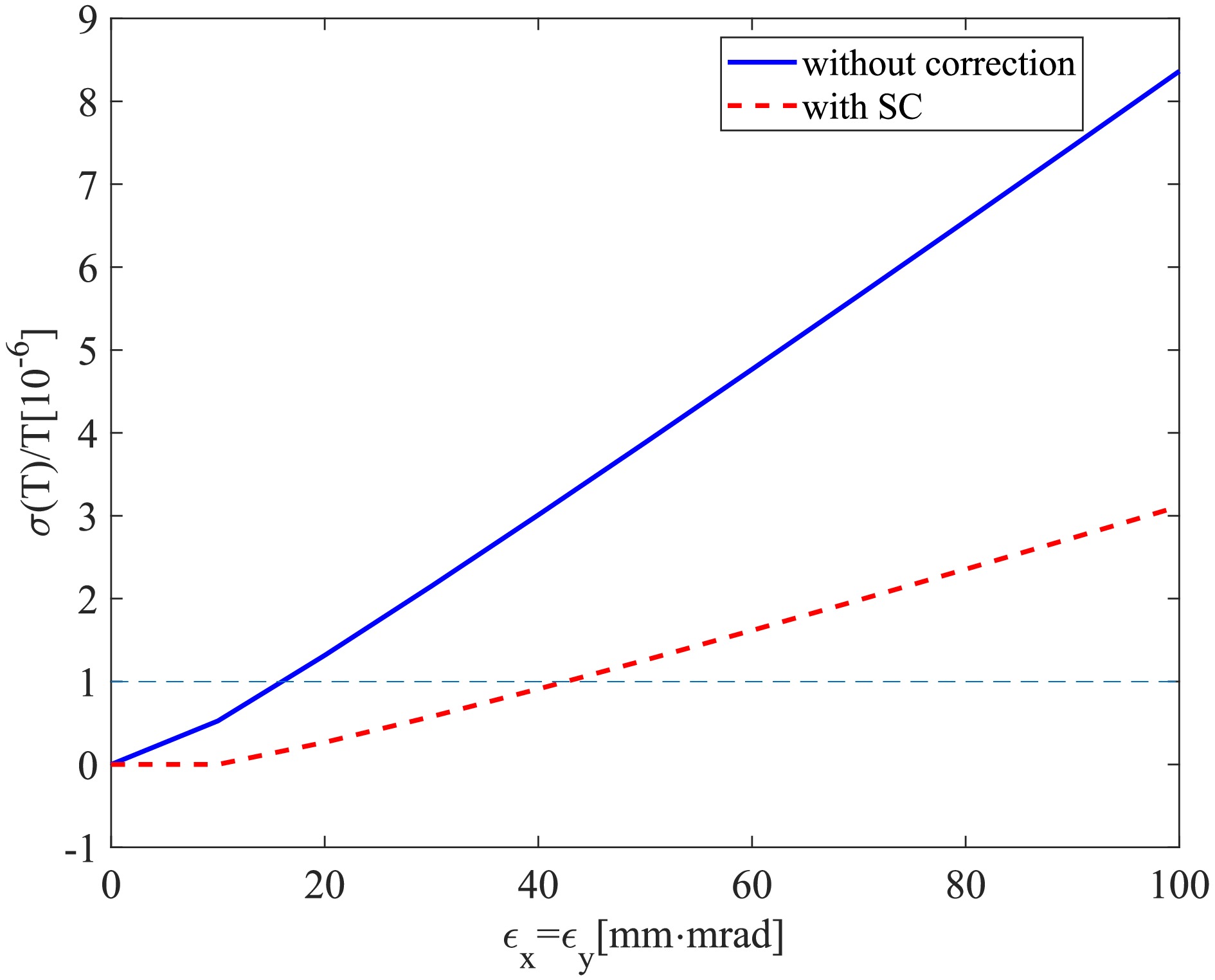

Figure 5 shows the revolution time distribution for two beams with the same momentum but different emittance: 10 and 100

$ {\rm mm\cdot mrad} $ , where SC denotes sextupole magnet corrections. In the calculation,$10^6 $ stored zero momentum deviation isochronous ions were used, the emittance was changed simultaneously in the horizontal and vertical planes, and the revolution time ($ T_0 $ ) of stored ions in the SRing is approximately 1.24$ \mu\text{s} $ . Three families of sextupole magnets were used to correct the transverse emittance influence, including the second order$ (t|\delta \delta) $ . When the emittance increases, the spread of revolution time increases and the central value also changes. The second effect is more important for the mass measurement experiments, because the mean value of the revolution time distribution is used for mass determination. This causes systematic errors and cannot be eliminated by increasing statistics. After the further corrections of the transverse emittance influence including the second order$ (t|\delta \delta) $ , the mean shift of the revolution time reduces from about 350 ps to 11 ps for transverse emittance of 100 mm·mrad. The FWHM of the distributions in Fig. 5 is 32.3 ps, 135.5 ps and 85.1 ps, respectively.

Figure 5. (color online) Revolution time distribution for beams with the same momentum but different emittance. The y-axis is a logarithmic scale.

As illustrated in Fig. 6, the revolution time spread increases linearly with the beam transverse emittance. In the simulations, we used

$10^6 $ zero momentum deviation isochronous ions and tracked for 100 turns. The emittance was changed simultaneously in the horizontal and vertical planes. With the sextupole correction,$ \sigma (T)/T \leq 1\times 10^{-6} $ will be reached with a transverse emittance of$ < 45$ $ {\rm mm\cdot mrad} $ in both planes for beams with the reference momentum, expanded from$ < 15 $ ${\rm mm\cdot mrad} $ without correction. -

For ions with the same momentum in the storage ring, their orbital length deviation and consequently the relative revolution time difference depends quadratically on the amplitude of the betatron oscillations, which is directly related to the transverse emittance as follow [33, 38]:

$ \Biggl(\frac{\Delta L}{L}\Biggr)_{\beta}\approx\frac {1}{4L_0}\int_0^{s}(\varepsilon_x \gamma_x(s) +\varepsilon_x h^{2}(s)\beta_x(s) +\varepsilon_y \gamma_y(s)){\rm d}s ,$

(4) where

$ \varepsilon_x $ and$ \varepsilon_y $ are the transverse emittance values in each plane.$ \beta_x(s) $ ,$ \gamma_x(s) $ , and$ \gamma_y(s) $ are the Twiss parameters of the storage ring.$ h(s)=\frac{1}{\rho(s)} $ is the bending power of the dipole field.When the transverse emittance increases, ions oscillate around the reference orbit with higher betatron oscillation amplitude. Then, they will have longer orbit length and revolution time. Large acceptance of the SRing is more crucial for IMS experiments of very short-lived nuclei with low production cross-sections. This means a high transmission efficiency from the HFRS to the SRing is desired, and the stored ions may have a large momentum spread and large transverse emittance. To increase the mass resolving power while keeping large acceptance of the SRing, the influence of transverse emittance on the revolution time spread should be reduced by using the sextupoles in the dispersion section of the SRing.

Figure 5 shows the revolution time distribution for two beams with the same momentum but different emittance: 10 and 100

$ {\rm mm\cdot mrad} $ , where SC denotes sextupole magnet corrections. In the calculation,$10^6 $ stored zero momentum deviation isochronous ions were used, the emittance was changed simultaneously in the horizontal and vertical planes, and the revolution time ($ T_0 $ ) of stored ions in the SRing is approximately 1.24$ \mu\text{s} $ . Three families of sextupole magnets were used to correct the transverse emittance influence, including the second order$ (t|\delta \delta) $ . When the emittance increases, the spread of revolution time increases and the central value also changes. The second effect is more important for the mass measurement experiments, because the mean value of the revolution time distribution is used for mass determination. This causes systematic errors and cannot be eliminated by increasing statistics. After the further corrections of the transverse emittance influence including the second order$ (t|\delta \delta) $ , the mean shift of the revolution time reduces from about 350 ps to 11 ps for transverse emittance of 100 mm·mrad. The FWHM of the distributions in Fig. 5 is 32.3 ps, 135.5 ps and 85.1 ps, respectively.

Figure 5. (color online) Revolution time distribution for beams with the same momentum but different emittance. The y-axis is a logarithmic scale.

As illustrated in Fig. 6, the revolution time spread increases linearly with the beam transverse emittance. In the simulations, we used

$10^6 $ zero momentum deviation isochronous ions and tracked for 100 turns. The emittance was changed simultaneously in the horizontal and vertical planes. With the sextupole correction,$ \sigma (T)/T \leq 1\times 10^{-6} $ will be reached with a transverse emittance of$ < 45$ $ {\rm mm\cdot mrad} $ in both planes for beams with the reference momentum, expanded from$ < 15 $ ${\rm mm\cdot mrad} $ without correction. -

For ions with the same momentum in the storage ring, their orbital length deviation and consequently the relative revolution time difference depends quadratically on the amplitude of the betatron oscillations, which is directly related to the transverse emittance as follow [33, 38]:

$ \Biggl(\frac{\Delta L}{L}\Biggr)_{\beta}\approx\frac {1}{4L_0}\int_0^{s}(\varepsilon_x \gamma_x(s) +\varepsilon_x h^{2}(s)\beta_x(s) +\varepsilon_y \gamma_y(s)){\rm d}s ,$

(4) where

$ \varepsilon_x $ and$ \varepsilon_y $ are the transverse emittance values in each plane.$ \beta_x(s) $ ,$ \gamma_x(s) $ , and$ \gamma_y(s) $ are the Twiss parameters of the storage ring.$ h(s)=\frac{1}{\rho(s)} $ is the bending power of the dipole field.When the transverse emittance increases, ions oscillate around the reference orbit with higher betatron oscillation amplitude. Then, they will have longer orbit length and revolution time. Large acceptance of the SRing is more crucial for IMS experiments of very short-lived nuclei with low production cross-sections. This means a high transmission efficiency from the HFRS to the SRing is desired, and the stored ions may have a large momentum spread and large transverse emittance. To increase the mass resolving power while keeping large acceptance of the SRing, the influence of transverse emittance on the revolution time spread should be reduced by using the sextupoles in the dispersion section of the SRing.

Figure 5 shows the revolution time distribution for two beams with the same momentum but different emittance: 10 and 100

$ {\rm mm\cdot mrad} $ , where SC denotes sextupole magnet corrections. In the calculation,$10^6 $ stored zero momentum deviation isochronous ions were used, the emittance was changed simultaneously in the horizontal and vertical planes, and the revolution time ($ T_0 $ ) of stored ions in the SRing is approximately 1.24$ \mu\text{s} $ . Three families of sextupole magnets were used to correct the transverse emittance influence, including the second order$ (t|\delta \delta) $ . When the emittance increases, the spread of revolution time increases and the central value also changes. The second effect is more important for the mass measurement experiments, because the mean value of the revolution time distribution is used for mass determination. This causes systematic errors and cannot be eliminated by increasing statistics. After the further corrections of the transverse emittance influence including the second order$ (t|\delta \delta) $ , the mean shift of the revolution time reduces from about 350 ps to 11 ps for transverse emittance of 100 mm·mrad. The FWHM of the distributions in Fig. 5 is 32.3 ps, 135.5 ps and 85.1 ps, respectively.

Figure 5. (color online) Revolution time distribution for beams with the same momentum but different emittance. The y-axis is a logarithmic scale.

As illustrated in Fig. 6, the revolution time spread increases linearly with the beam transverse emittance. In the simulations, we used

$10^6 $ zero momentum deviation isochronous ions and tracked for 100 turns. The emittance was changed simultaneously in the horizontal and vertical planes. With the sextupole correction,$ \sigma (T)/T \leq 1\times 10^{-6} $ will be reached with a transverse emittance of$ < 45$ $ {\rm mm\cdot mrad} $ in both planes for beams with the reference momentum, expanded from$ < 15 $ ${\rm mm\cdot mrad} $ without correction. -

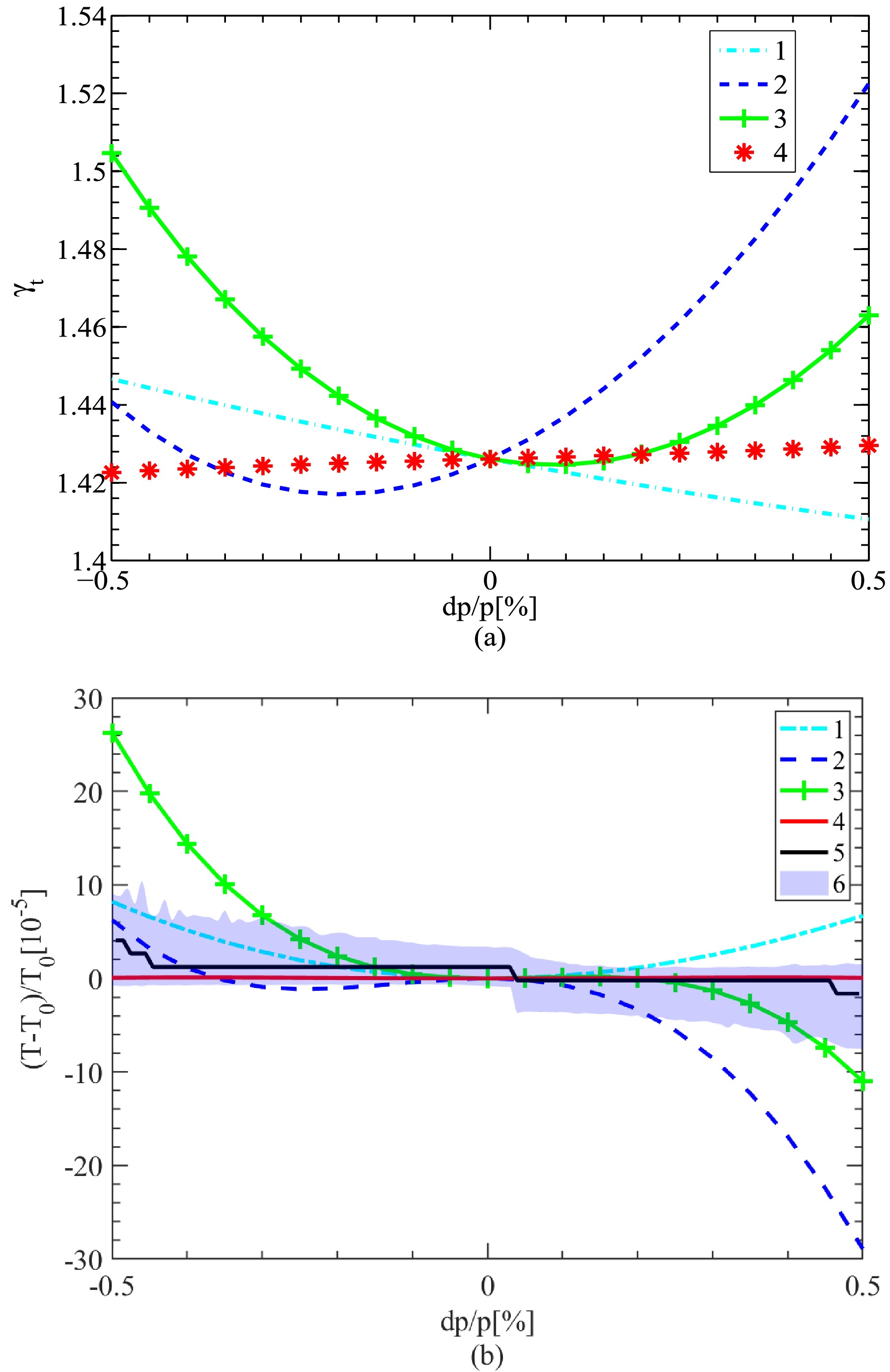

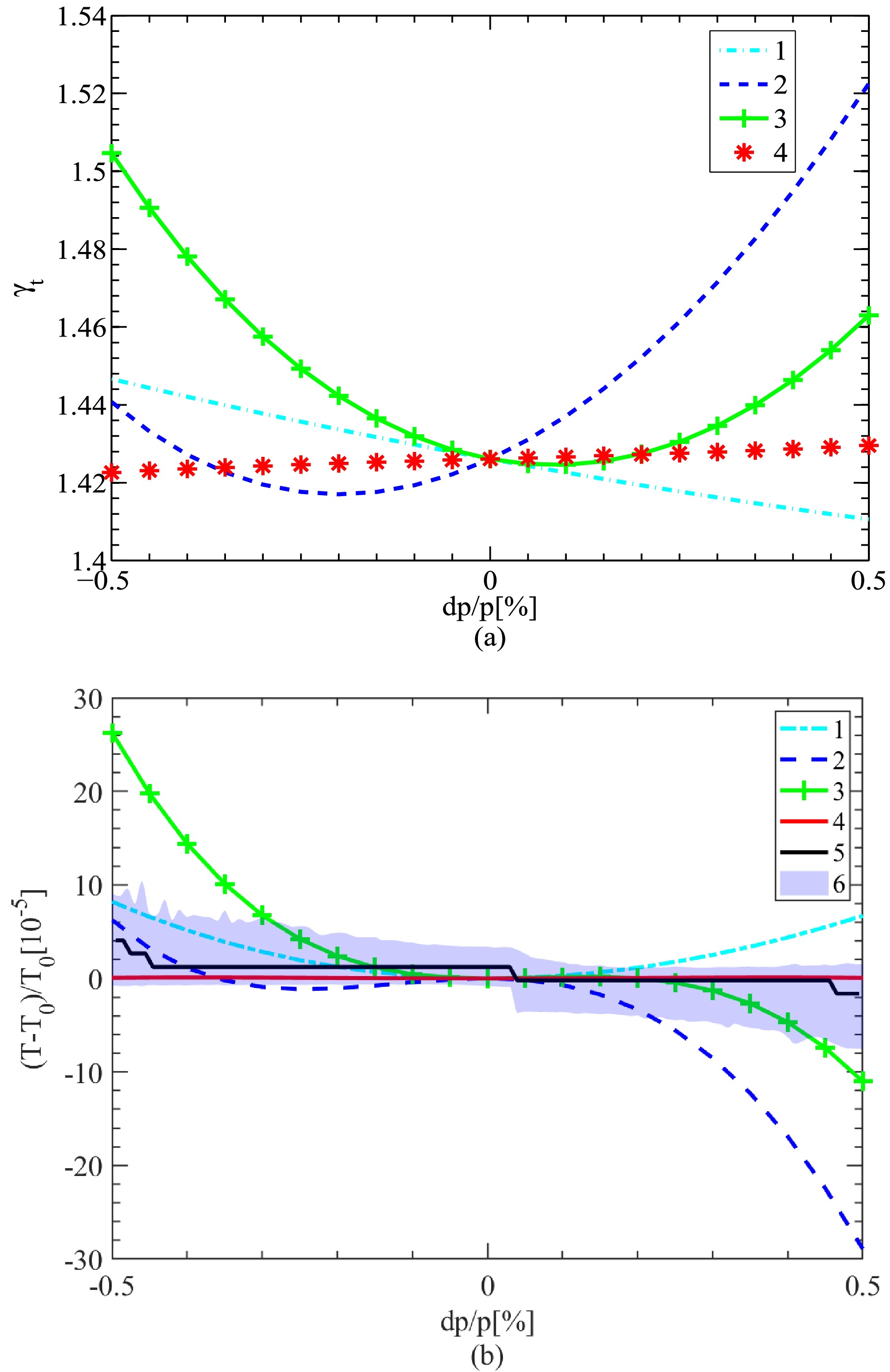

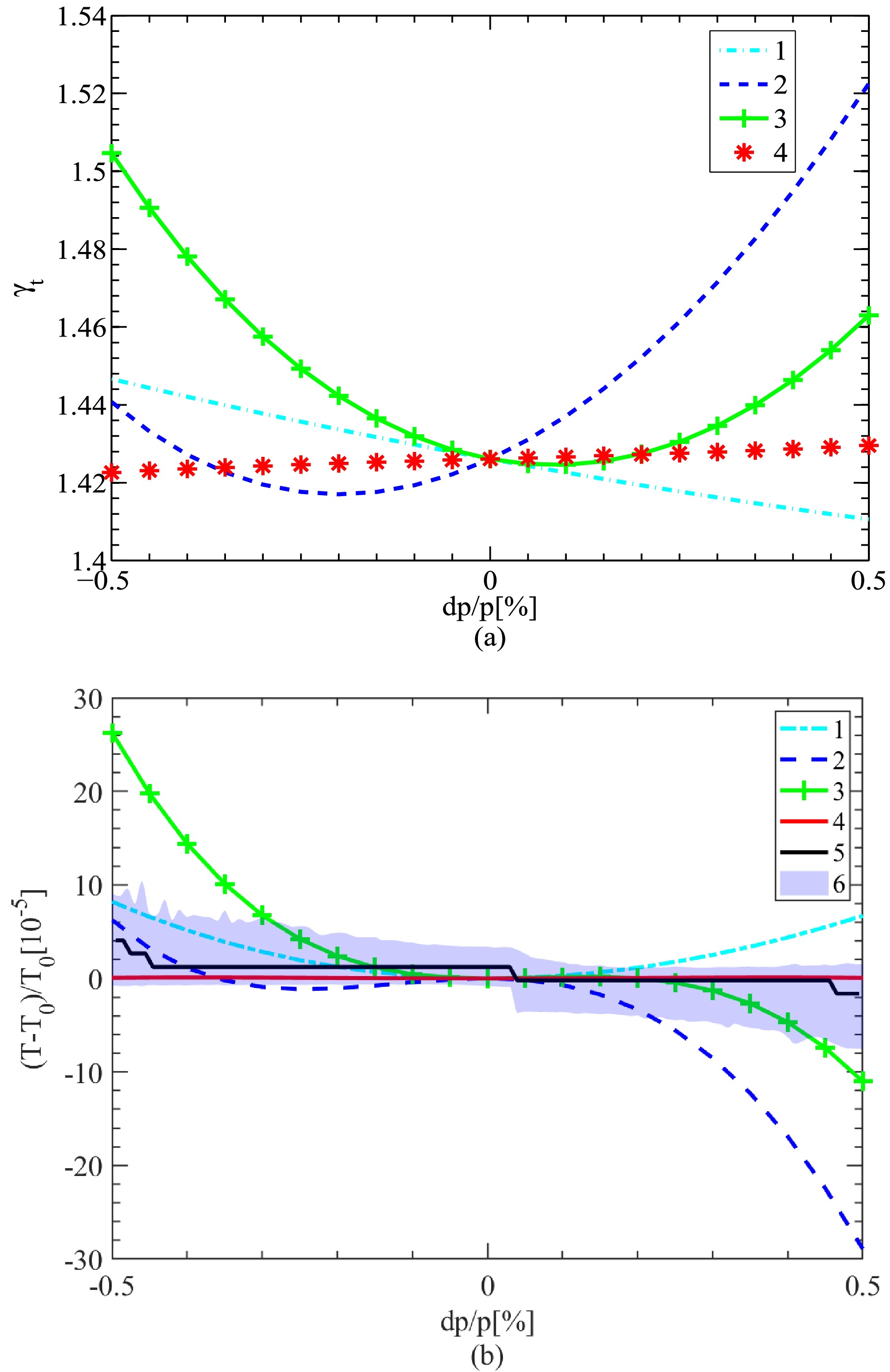

For the large aperture magnet design of the SRing, the imperfection of the magnetic field changes the designed dispersion and

$ \beta- $ function of the storage ring. This also results in a change of$ \gamma_t $ of the storage ring as a function of momentum deviation. The variation of revolution time of the stored ions as a function of momentum deviation will also be influenced. The influence of magnetic field imperfections on the revolution time and corresponding correction scheme with sextupoles and octupoles were investigated. In the calculation, the transverse emittance setting is 30$ {\rm mm\cdot mrad} $ . The main ingredients considered here are the higher-order field components of dipoles and fringe fields of dipoles and quadrupoles.The dipole magnetic field homogeneity is crucial for the time resolution, which can be described by a series of higher-order field indices

$ n_i $ as [30]$ B_{(x,y = 0)} = B_0 \bigg[1- n_1\Biggl({\frac{x}{{\rho}}}\Biggr)- n_2\Biggl({\frac{x}{{\rho}}}\Biggr)^{2}- n_i\Biggl({\frac{x}{{\rho}}}\Biggr)^{i}+\cdots \bigg], $

(5) where ρ is the reference radius of the dipole magnet.

In the calculation, the indices

$ n_1 $ = 0.0059,$ n_2 $ = 0.3491,$ n_3 $ = 41.2653,$ n_4 $ = 243.4654, and$ n_5 $ = 7149.2430, and the dipole magnetic field$ B = 1.252~ T $ . One can see that the higher-order field components of the dipoles lead to variation of revolution time, as shown by curve 1 in Fig. 7. This implies that, in the design of the magnet, the higher-order field of the dipoles should be minimized for the IMS experiments. The influence of the higher-order field components of dipoles can be completely compensated by the corresponding order of magnetic field.

Figure 7. (color online) Transition energy

$ \gamma_t $ (a) and relative variation of revolution time (b) as a function of momentum deviation. For curves (1): only with the influence of the higher-order field components of dipoles; (2): with only the influence of the fringe fields of dipoles and quadrupoles; (3): with both (1) and (2); (4): an correction of (3) by three families of sextupole and one family of octupole; (5): The influence of base line of (4) by transverse emittance 30 mm·mrad; and the shaded area (6) is the FWHM of (5).The quadrupoles in the SRing will have a maximum aperture of 0.32 m, which will lead to strong extended fringe field proportional to its pole field [39]. The influence of the quadrupole fringe field in the SRing was analyzed by the mode "F F 1" in GICOSY code, as illustrated by curve 2 in Fig. 7. The change of the optics leads to a change of the tune and correspondingly of the chromaticity. The fringe fields will have a considerable influence on orbit length of ions away from the reference orbit.

To mitigate the higher-order aberrations caused by the higher-order field components of dipoles and fringe fields of dipoles and quadrupoles, several families of sextupoles and octupoles are introduced. Adjustment of quadupoles is needed to correct the center value of

$ \gamma_t $ .The corrections result is shown as curve 4 in Fig. 7. Finally, with three sextupole families and one octupole family corrections,

$ \sigma (T)/T $ was reduced to$ 4.9\times 10^{-7} $ within the range of momentum acceptance of$ \pm0.2$ %. According to the symmetry of SRing shown in Fig. 1, each magnet family includes 4 magnets with same strength.The curve 5 and the shaded area 6 show the influence of 30 mm·mrad transverse emittance. Usually, such influence can be mitigated by filtering of the frequency components with transverse betatron tunes and their high order combinations in the time sequence signals [40].

-

For the large aperture magnet design of the SRing, the imperfection of the magnetic field changes the designed dispersion and

$ \beta- $ function of the storage ring. This also results in a change of$ \gamma_t $ of the storage ring as a function of momentum deviation. The variation of revolution time of the stored ions as a function of momentum deviation will also be influenced. The influence of magnetic field imperfections on the revolution time and corresponding correction scheme with sextupoles and octupoles were investigated. In the calculation, the transverse emittance setting is 30$ {\rm mm\cdot mrad} $ . The main ingredients considered here are the higher-order field components of dipoles and fringe fields of dipoles and quadrupoles.The dipole magnetic field homogeneity is crucial for the time resolution, which can be described by a series of higher-order field indices

$ n_i $ as [30]$ B_{(x,y = 0)} = B_0 \bigg[1- n_1\Biggl({\frac{x}{{\rho}}}\Biggr)- n_2\Biggl({\frac{x}{{\rho}}}\Biggr)^{2}- n_i\Biggl({\frac{x}{{\rho}}}\Biggr)^{i}+\cdots \bigg], $

(5) where ρ is the reference radius of the dipole magnet.

In the calculation, the indices

$ n_1 $ = 0.0059,$ n_2 $ = 0.3491,$ n_3 $ = 41.2653,$ n_4 $ = 243.4654, and$ n_5 $ = 7149.2430, and the dipole magnetic field$ B = 1.252~ T $ . One can see that the higher-order field components of the dipoles lead to variation of revolution time, as shown by curve 1 in Fig. 7. This implies that, in the design of the magnet, the higher-order field of the dipoles should be minimized for the IMS experiments. The influence of the higher-order field components of dipoles can be completely compensated by the corresponding order of magnetic field.

Figure 7. (color online) Transition energy

$ \gamma_t $ (a) and relative variation of revolution time (b) as a function of momentum deviation. For curves (1): only with the influence of the higher-order field components of dipoles; (2): with only the influence of the fringe fields of dipoles and quadrupoles; (3): with both (1) and (2); (4): an correction of (3) by three families of sextupole and one family of octupole; (5): The influence of base line of (4) by transverse emittance 30 mm·mrad; and the shaded area (6) is the FWHM of (5).The quadrupoles in the SRing will have a maximum aperture of 0.32 m, which will lead to strong extended fringe field proportional to its pole field [39]. The influence of the quadrupole fringe field in the SRing was analyzed by the mode "F F 1" in GICOSY code, as illustrated by curve 2 in Fig. 7. The change of the optics leads to a change of the tune and correspondingly of the chromaticity. The fringe fields will have a considerable influence on orbit length of ions away from the reference orbit.

To mitigate the higher-order aberrations caused by the higher-order field components of dipoles and fringe fields of dipoles and quadrupoles, several families of sextupoles and octupoles are introduced. Adjustment of quadupoles is needed to correct the center value of

$ \gamma_t $ .The corrections result is shown as curve 4 in Fig. 7. Finally, with three sextupole families and one octupole family corrections,

$ \sigma (T)/T $ was reduced to$ 4.9\times 10^{-7} $ within the range of momentum acceptance of$ \pm0.2$ %. According to the symmetry of SRing shown in Fig. 1, each magnet family includes 4 magnets with same strength.The curve 5 and the shaded area 6 show the influence of 30 mm·mrad transverse emittance. Usually, such influence can be mitigated by filtering of the frequency components with transverse betatron tunes and their high order combinations in the time sequence signals [40].

-

For the large aperture magnet design of the SRing, the imperfection of the magnetic field changes the designed dispersion and

$ \beta- $ function of the storage ring. This also results in a change of$ \gamma_t $ of the storage ring as a function of momentum deviation. The variation of revolution time of the stored ions as a function of momentum deviation will also be influenced. The influence of magnetic field imperfections on the revolution time and corresponding correction scheme with sextupoles and octupoles were investigated. In the calculation, the transverse emittance setting is 30$ {\rm mm\cdot mrad} $ . The main ingredients considered here are the higher-order field components of dipoles and fringe fields of dipoles and quadrupoles.The dipole magnetic field homogeneity is crucial for the time resolution, which can be described by a series of higher-order field indices

$ n_i $ as [30]$ B_{(x,y = 0)} = B_0 \bigg[1- n_1\Biggl({\frac{x}{{\rho}}}\Biggr)- n_2\Biggl({\frac{x}{{\rho}}}\Biggr)^{2}- n_i\Biggl({\frac{x}{{\rho}}}\Biggr)^{i}+\cdots \bigg], $

(5) where ρ is the reference radius of the dipole magnet.

In the calculation, the indices

$ n_1 $ = 0.0059,$ n_2 $ = 0.3491,$ n_3 $ = 41.2653,$ n_4 $ = 243.4654, and$ n_5 $ = 7149.2430, and the dipole magnetic field$ B = 1.252~ T $ . One can see that the higher-order field components of the dipoles lead to variation of revolution time, as shown by curve 1 in Fig. 7. This implies that, in the design of the magnet, the higher-order field of the dipoles should be minimized for the IMS experiments. The influence of the higher-order field components of dipoles can be completely compensated by the corresponding order of magnetic field.

Figure 7. (color online) Transition energy

$ \gamma_t $ (a) and relative variation of revolution time (b) as a function of momentum deviation. For curves (1): only with the influence of the higher-order field components of dipoles; (2): with only the influence of the fringe fields of dipoles and quadrupoles; (3): with both (1) and (2); (4): an correction of (3) by three families of sextupole and one family of octupole; (5): The influence of base line of (4) by transverse emittance 30 mm·mrad; and the shaded area (6) is the FWHM of (5).The quadrupoles in the SRing will have a maximum aperture of 0.32 m, which will lead to strong extended fringe field proportional to its pole field [39]. The influence of the quadrupole fringe field in the SRing was analyzed by the mode "F F 1" in GICOSY code, as illustrated by curve 2 in Fig. 7. The change of the optics leads to a change of the tune and correspondingly of the chromaticity. The fringe fields will have a considerable influence on orbit length of ions away from the reference orbit.

To mitigate the higher-order aberrations caused by the higher-order field components of dipoles and fringe fields of dipoles and quadrupoles, several families of sextupoles and octupoles are introduced. Adjustment of quadupoles is needed to correct the center value of

$ \gamma_t $ .The corrections result is shown as curve 4 in Fig. 7. Finally, with three sextupole families and one octupole family corrections,

$ \sigma (T)/T $ was reduced to$ 4.9\times 10^{-7} $ within the range of momentum acceptance of$ \pm0.2$ %. According to the symmetry of SRing shown in Fig. 1, each magnet family includes 4 magnets with same strength.The curve 5 and the shaded area 6 show the influence of 30 mm·mrad transverse emittance. Usually, such influence can be mitigated by filtering of the frequency components with transverse betatron tunes and their high order combinations in the time sequence signals [40].

-

The isochronous modes with three transition energy settings of the SRing is designed for precise mass and half-life measurements of short-lived exotic nuclide. The influence of transverse emittance and field imperfections, including nonlinear field errors of dipoles and fringe fields of dipoles and quadrupoles, on the revolution time resolution of the isochronous mode has been studied.

The calculations show that the revolution time spread strongly depends on the beam transverse emittance. When the emittance increases, the width becomes large and the center of the revolution time is shifted. Although such influence is large, but it can be mitigated by filtering of the time sequence signals based on accelerator theory of transverse motions.

Focusing on the lowest transition energy,

$ \gamma_t=1.43 $ , the influence of field perfections, such as higher-order field components of dipoles and fringe field of dipole and quadrupole magnets, on the revolution time resolution are studied. The higher-order magnets, such as sextupole and octupole families are used to optimize the time resolution.With three families of sextupole and one family of octupole, a mass resolution of

$ R({\rm FWHM}) = 1\times 10^6 $ to$ \sigma (T)=T \sim 4.9\times 10^{-7} $ is reached, within the momentum. -

The isochronous modes with three transition energy settings of the SRing is designed for precise mass and half-life measurements of short-lived exotic nuclide. The influence of transverse emittance and field imperfections, including nonlinear field errors of dipoles and fringe fields of dipoles and quadrupoles, on the revolution time resolution of the isochronous mode has been studied.

The calculations show that the revolution time spread strongly depends on the beam transverse emittance. When the emittance increases, the width becomes large and the center of the revolution time is shifted. Although such influence is large, but it can be mitigated by filtering of the time sequence signals based on accelerator theory of transverse motions.

Focusing on the lowest transition energy,

$ \gamma_t=1.43 $ , the influence of field perfections, such as higher-order field components of dipoles and fringe field of dipole and quadrupole magnets, on the revolution time resolution are studied. The higher-order magnets, such as sextupole and octupole families are used to optimize the time resolution.With three families of sextupole and one family of octupole, a mass resolution of

$ R({\rm FWHM}) = 1\times 10^6 $ to$ \sigma (T)=T \sim 4.9\times 10^{-7} $ is reached, within the momentum. -

The isochronous modes with three transition energy settings of the SRing is designed for precise mass and half-life measurements of short-lived exotic nuclide. The influence of transverse emittance and field imperfections, including nonlinear field errors of dipoles and fringe fields of dipoles and quadrupoles, on the revolution time resolution of the isochronous mode has been studied.

The calculations show that the revolution time spread strongly depends on the beam transverse emittance. When the emittance increases, the width becomes large and the center of the revolution time is shifted. Although such influence is large, but it can be mitigated by filtering of the time sequence signals based on accelerator theory of transverse motions.

Focusing on the lowest transition energy,

$ \gamma_t=1.43 $ , the influence of field perfections, such as higher-order field components of dipoles and fringe field of dipole and quadrupole magnets, on the revolution time resolution are studied. The higher-order magnets, such as sextupole and octupole families are used to optimize the time resolution.With three families of sextupole and one family of octupole, a mass resolution of

$ R({\rm FWHM}) = 1\times 10^6 $ to$ \sigma (T)=T \sim 4.9\times 10^{-7} $ is reached, within the momentum.

Design optimization of isochronous mode in the HIAF-SRing

- Received Date: 2025-01-29

- Available Online: 2025-12-15

Abstract: The measurement of mass, or equivalently the binding energy, of exotic nuclei has reached the limits of nuclear existence, which are characterized by tiny production cross-sections and short half-lives. The isochronous mode of the Spectrometer Ring at the High Intensity heavy-ion Accelerator Facility project in China (HIAF-SRing) offers the capacity for such measurements. However, many factors limit the revolution time resolution of the isochronous mode of the large acceptance HIAF-SRing. Nonlinear field errors as well as fringe fields of the wide aperture dipoles and quadrupoles strongly excite the higher-order aberrations, which negatively affect the revolution time resolution. Moreover, the transverse emittance of the beam is inversely proportional to the revolution time resolution. Their influence is investigated here, and a possible correction scheme with sextupoles and octupoles is shown. With higher-order corrections, a mass resolution of

Abstract

Abstract HTML

HTML Reference

Reference Related

Related PDF

PDF

DownLoad:

DownLoad: