-

Proton radioactivity, discovered as a significant spontaneous decay mode in the study of exotic nuclei beyond the

$ \beta $ -stability line, manifests as single-proton and two-proton (2p) radioactivity. First detected by Jackson et al. during the 1970s in the isomeric state of 53Com [1, 2], it was later independently observed from ground states in 151Lu [3] (by Hofmann) and 147Tm [4] (by Klepper). Following these key findings, numerous proton-emitting radionuclides have been identified. To date, research has characterized over 40 such emitters in ground and isomeric states across the Z=51~83 region. Although proton radioactivity exists in nuclei with Z<50, accurately measuring their extremely short half-lives remains challenging because of current limitations in experimental techniques and detection equipment [5]. The phenomenon of true two-proton radioactivity (requiring$ Q_{\rm{2p}} > $ 0 and$ Q_{\rm{p} } < $ 0, where$ Q_{\rm{p}} $ and$ Q_{\rm{2p}} $ represent the single-proton radioactivity released energy and two-proton radioactivity released energy) was first established theoretically by Zel'dovich and Goldansky in the 1960s [6−8]. It was initially observed experimentally in 45Fe at GSI and GANIL in 2002 [9, 10]. Since then, this decay mode has been found in other neutron-deficient nuclei, specifically 54Zn, 48Ni, 19Mg, and 67Kr [11−14]. Before 2002, the not true 2p radioactivity ($ Q_{\rm{2p}} > $ 0 and$ Q_{\rm{p}} > $ 0) was observed from 6Be, 12O, and 16Ne [15−20]. The exploration of nuclear structure and potential proton drip line [21−26] is anticipated to advance through the discovery of more proton-emitting radionuclides, facilitated by upgrades to experimental facilities and methods. As a valuable tool for investigating nuclear properties such as released energy and half-life, proton radioactivity is becoming an increasingly important topic in the field [27−30].Numerous empirical formulas and theoretical models have been developed to study the half-life of proton radioactivity. In the field of single-proton radioactivity, these include the single-folding model [31, 32], generalized liquid drop model (GLDM) [33], relativistic density functional theory [34], density-dependent M3Y effective interactions [35, 36], phenomenological unified fission model [37, 38], distorted-wave Born approximation [39], universal decay law of proton radioactivity (UDLP) [40], Gamow-like model (GLM) [24, 41], Coulomb and proximity potential model (CPPM) [42], deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum [43], and triaxial relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum [44], among others. In the field of two-proton radioactivity, these include the direct decay model [45−49], the simultaneous versus sequential decay model [7, 50], diproton model [8, 51], and three-body model, among others [49, 52−55]. Furthermore, empirical formulas serve as critical analytical tools in two-proton emission studies, and they are predominantly derived from the Geiger-Nuttall (G-N) law [56]. Representative formulations include those proposed by Sreeja et al. [57] and Liu et al. [58].

The GLM, a simple phenomenological model, was initially proposed by Zdeb et al. to study

$ \alpha $ decay [59]. The calculated$ \alpha $ decay half-life of the model showed close agreement with experimental values, prompting its extension to proton radioactivity investigation [41]. In this application, the GLM demonstrated high sensitivity of proton radioactivity half-lives to the external barrier position, emphasizing that accurate potential energy curves are vital in calculations. The GLM represents the external potential via the Coulomb and centrifugal potentials and the internal potential as a square well potential. This method has considerably deeper physical foundations and retains the simplicity of the Viola-Seaborg approach [41]. In 2019, Chen et al. modified the GLM to consider the screening effect of the Coulomb interaction between the emitted proton and daughter nuclei on Hulthen potential [24]. In 2021, Liu et al. [60] applied the GLM to two-proton radioactivity research. Subsequently, in 2022, Zhu et al. [61] investigated two-proton radioactivity using the GLM, considering electrostatic screening effects. More recently, in 2024, Zhang et al. [62] developed the deformed Gamow-like model (D-GLM-zhang) to examine how angular momentum affects the half-life of proton radioactivity. Insights into the final Nilsson configuration, and consequently, valuable information about nuclear shape, are provided by studying the half-life associated with proton radioactivity in deformed nuclei. This paper modified the Coulomb interaction between the emitted proton and daughter nucleus by considering the deformation effect of the daughter nucleus and systematically calculated the half-lives of single-proton and two-proton radioactive nuclei.The remainder of this article is organized as follows: Sec. II discusses the theoretical framework of the computational model in detail, Sec. III presents and discusses the results, and Sec. IV summarizes the findings.

-

Proton radioactivity, discovered as a significant spontaneous decay mode in the study of exotic nuclei beyond the

$ \beta $ -stability line, manifests in two types: single-proton and two-proton (2p) radioactivity. First detected by Jackson and colleagues during the 1970s in the isomeric state of 53Com [1, 2], it was later independently observed from ground states in 151Lu [3] (by Hofmann) and 147Tm [4] (by Klepper). Following these key findings, numerous proton-emitting radionuclides have been identified. To date, research has characterized over forty such emitters in ground and isomeric states across the Z=51~83 region. While proton radioactivity also exists in nuclei with Z<50, accurately measuring their extremely short half-lives remains challenging due to current limitations in experimental techniques and detection equipment [5]. The phenomenon of true two-proton radioactivity (requiring$ Q_{\rm{2p}} > $ 0 and$ Q_{\rm{p} } < $ 0, where$ Q_{\rm{p}} $ and$ Q_{\rm{2p}} $ represent the single-proton radioactivity released energy and two-proton radioactivity released energy) was first established theoretically by Zel'dovich and Goldanskii in the 1960s [6−8]. It was initially observed experimentally in 45Fe at GSI and GANIL in 2002 [9, 10]. Since then, this decay mode has also been found in other neutron-deficient nuclei, specifically 54Zn, 48Ni, 19 Mg, and 67Kr [11−14]. Before 2002, the not true 2p radioactivity($ Q_{\rm{2p}} > $ 0 and$ Q_{\rm{p}} > $ 0) was observed from 6Be, 12O, and 16Ne [15−20]. The exploration of nuclear structure and the potential proton drip line [21−26] is anticipated to advance through the discovery of more proton-emitting radionuclides, facilitated by upgrades to experimental facilities and methods. As a valuable tool for investigating nuclear properties such as released energy and half-life, proton radioactivity is becoming an increasingly important topic in the field [27−30].To study the half-life of proton radioactivity, numerous empirical formulas and theoretical models have been developed. In the field of single-proton radioactivity, these include the single-folding model (SFM) [31, 32], the generalized liquid drop model (GLDM) [33], the relativistic density functional theory (RDFT) [34], the density-dependent M3Y (DDM3Y) effective interactions [35, 36], the phenomenological unified fission model (PUFM) [37, 38], the distorted-wave Born approximation (DWBA) [39], the universal decay law of proton radioactivity (UDLP) [40], the Gamow-like model (GLM) [24, 41], the Coulomb and proximity potential model (CPPM) [42] the deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum (DRHBc) [43] and the triaxial relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum (TRHBc) [44], among others. In the field of two-proton radioactivity, these include the direct decay model [45−49], the simultaneous versus sequential decay model [7, 50], the diproton model [8, 51], and the three-body model, among others [49, 52−55]. Furthermore, empirical formulas serve as critical analytical tools in two-proton emission studies, predominantly derived from the Geiger-Nuttall (G-N) law [56]. Representative formulations include those proposed by Sreeja et al [57]. and Liu et al [58].

The GLM, a simple phenomenological model, was initially proposed by Zdeb et al to study

$ \alpha $ decay [67]. The model's calculated$ \alpha $ decay half-life showed close agreement with experimental values, prompting to its extension to proton radioactivity investigation [41]. In this application, the GLM demonstrated high sensitivity of proton radioactivity half-lives to the external barrier position, emphasizing that accurate potential energy curves are vital in calculations. The GLM represents the external potential via the Coulomb and centrifugal potentials and the internal potential as a square well potential. This method has much deeper physical foundations and retains the simplicity of the Viola-Seaborg approach [41]. In 2019, Chen et al modified the GLM to account for the screening effect of the Coulomb interaction between emitted proton and daughter nuclei on Hulthen potential [24]. In 2021, Liu et al [68] applied the GLM to two-proton radioactivity research. Subsequently, in 2022, Zhu et al [69] investigated two-proton radioactivity using the GLM, considering electrostatic screening effects. More recently, in 2024, Zhang et al developed the deformed Gamow-like Model (D-GLM-zhang) [70] to examine how angular momentum impacts the half-life of proton radioactivity. Insights into the final Nilsson configuration and consequently valuable information about nuclear shape—are provided by studying the half-life associated with proton radioactivity in deformed nuclei. This paper modified the Coulomb interaction between the emitted proton and daughter nucleus by considering the deformation effect of the daughter nucleus, and systematically calculated the half-lives of single-proton and two-proton radioactive nuclei.The structure of this article is as follows: Section 2 discusses the theoretical framework of the computational model in detail, Section 3 presents and discusses the results, and Section 4 summarizes the findings.

-

Proton radioactivity, discovered as a significant spontaneous decay mode in the study of exotic nuclei beyond the

$ \beta $ -stability line, manifests as single-proton and two-proton (2p) radioactivity. First detected by Jackson et al. during the 1970s in the isomeric state of 53Com [1, 2], it was later independently observed from ground states in 151Lu [3] (by Hofmann) and 147Tm [4] (by Klepper). Following these key findings, numerous proton-emitting radionuclides have been identified. To date, research has characterized over 40 such emitters in ground and isomeric states across the Z=51~83 region. Although proton radioactivity exists in nuclei with Z<50, accurately measuring their extremely short half-lives remains challenging because of current limitations in experimental techniques and detection equipment [5]. The phenomenon of true two-proton radioactivity (requiring$ Q_{\rm{2p}} > $ 0 and$ Q_{\rm{p} } < $ 0, where$ Q_{\rm{p}} $ and$ Q_{\rm{2p}} $ represent the single-proton radioactivity released energy and two-proton radioactivity released energy) was first established theoretically by Zel'dovich and Goldansky in the 1960s [6−8]. It was initially observed experimentally in 45Fe at GSI and GANIL in 2002 [9, 10]. Since then, this decay mode has been found in other neutron-deficient nuclei, specifically 54Zn, 48Ni, 19Mg, and 67Kr [11−14]. Before 2002, the not true 2p radioactivity ($ Q_{\rm{2p}} > $ 0 and$ Q_{\rm{p}} > $ 0) was observed from 6Be, 12O, and 16Ne [15−20]. The exploration of nuclear structure and potential proton drip line [21−26] is anticipated to advance through the discovery of more proton-emitting radionuclides, facilitated by upgrades to experimental facilities and methods. As a valuable tool for investigating nuclear properties such as released energy and half-life, proton radioactivity is becoming an increasingly important topic in the field [27−30].Numerous empirical formulas and theoretical models have been developed to study the half-life of proton radioactivity. In the field of single-proton radioactivity, these include the single-folding model [31, 32], generalized liquid drop model (GLDM) [33], relativistic density functional theory [34], density-dependent M3Y effective interactions [35, 36], phenomenological unified fission model [37, 38], distorted-wave Born approximation [39], universal decay law of proton radioactivity (UDLP) [40], Gamow-like model (GLM) [24, 41], Coulomb and proximity potential model (CPPM) [42], deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum [43], and triaxial relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum [44], among others. In the field of two-proton radioactivity, these include the direct decay model [45−49], the simultaneous versus sequential decay model [7, 50], diproton model [8, 51], and three-body model, among others [49, 52−55]. Furthermore, empirical formulas serve as critical analytical tools in two-proton emission studies, and they are predominantly derived from the Geiger-Nuttall (G-N) law [56]. Representative formulations include those proposed by Sreeja et al. [57] and Liu et al. [58].

The GLM, a simple phenomenological model, was initially proposed by Zdeb et al. to study

$ \alpha $ decay [59]. The calculated$ \alpha $ decay half-life of the model showed close agreement with experimental values, prompting its extension to proton radioactivity investigation [41]. In this application, the GLM demonstrated high sensitivity of proton radioactivity half-lives to the external barrier position, emphasizing that accurate potential energy curves are vital in calculations. The GLM represents the external potential via the Coulomb and centrifugal potentials and the internal potential as a square well potential. This method has considerably deeper physical foundations and retains the simplicity of the Viola-Seaborg approach [41]. In 2019, Chen et al. modified the GLM to consider the screening effect of the Coulomb interaction between the emitted proton and daughter nuclei on Hulthen potential [24]. In 2021, Liu et al. [60] applied the GLM to two-proton radioactivity research. Subsequently, in 2022, Zhu et al. [61] investigated two-proton radioactivity using the GLM, considering electrostatic screening effects. More recently, in 2024, Zhang et al. [62] developed the deformed Gamow-like model (D-GLM-zhang) to examine how angular momentum affects the half-life of proton radioactivity. Insights into the final Nilsson configuration, and consequently, valuable information about nuclear shape, are provided by studying the half-life associated with proton radioactivity in deformed nuclei. This paper modified the Coulomb interaction between the emitted proton and daughter nucleus by considering the deformation effect of the daughter nucleus and systematically calculated the half-lives of single-proton and two-proton radioactive nuclei.The remainder of this article is organized as follows: Sec. II discusses the theoretical framework of the computational model in detail, Sec. III presents and discusses the results, and Sec. IV summarizes the findings.

-

Proton radioactivity, discovered as a significant spontaneous decay mode in the study of exotic nuclei beyond the

$ \beta $ -stability line, manifests as single-proton and two-proton (2p) radioactivity. First detected by Jackson et al. during the 1970s in the isomeric state of 53Com [1, 2], it was later independently observed from ground states in 151Lu [3] (by Hofmann) and 147Tm [4] (by Klepper). Following these key findings, numerous proton-emitting radionuclides have been identified. To date, research has characterized over 40 such emitters in ground and isomeric states across the Z=51~83 region. Although proton radioactivity exists in nuclei with Z<50, accurately measuring their extremely short half-lives remains challenging because of current limitations in experimental techniques and detection equipment [5]. The phenomenon of true two-proton radioactivity (requiring$ Q_{\rm{2p}} > $ 0 and$ Q_{\rm{p} } < $ 0, where$ Q_{\rm{p}} $ and$ Q_{\rm{2p}} $ represent the single-proton radioactivity released energy and two-proton radioactivity released energy) was first established theoretically by Zel'dovich and Goldansky in the 1960s [6−8]. It was initially observed experimentally in 45Fe at GSI and GANIL in 2002 [9, 10]. Since then, this decay mode has been found in other neutron-deficient nuclei, specifically 54Zn, 48Ni, 19Mg, and 67Kr [11−14]. Before 2002, the not true 2p radioactivity ($ Q_{\rm{2p}} > $ 0 and$ Q_{\rm{p}} > $ 0) was observed from 6Be, 12O, and 16Ne [15−20]. The exploration of nuclear structure and potential proton drip line [21−26] is anticipated to advance through the discovery of more proton-emitting radionuclides, facilitated by upgrades to experimental facilities and methods. As a valuable tool for investigating nuclear properties such as released energy and half-life, proton radioactivity is becoming an increasingly important topic in the field [27−30].Numerous empirical formulas and theoretical models have been developed to study the half-life of proton radioactivity. In the field of single-proton radioactivity, these include the single-folding model [31, 32], generalized liquid drop model (GLDM) [33], relativistic density functional theory [34], density-dependent M3Y effective interactions [35, 36], phenomenological unified fission model [37, 38], distorted-wave Born approximation [39], universal decay law of proton radioactivity (UDLP) [40], Gamow-like model (GLM) [24, 41], Coulomb and proximity potential model (CPPM) [42], deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum [43], and triaxial relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum [44], among others. In the field of two-proton radioactivity, these include the direct decay model [45−49], the simultaneous versus sequential decay model [7, 50], diproton model [8, 51], and three-body model, among others [49, 52−55]. Furthermore, empirical formulas serve as critical analytical tools in two-proton emission studies, and they are predominantly derived from the Geiger-Nuttall (G-N) law [56]. Representative formulations include those proposed by Sreeja et al. [57] and Liu et al. [58].

The GLM, a simple phenomenological model, was initially proposed by Zdeb et al. to study

$ \alpha $ decay [59]. The calculated$ \alpha $ decay half-life of the model showed close agreement with experimental values, prompting its extension to proton radioactivity investigation [41]. In this application, the GLM demonstrated high sensitivity of proton radioactivity half-lives to the external barrier position, emphasizing that accurate potential energy curves are vital in calculations. The GLM represents the external potential via the Coulomb and centrifugal potentials and the internal potential as a square well potential. This method has considerably deeper physical foundations and retains the simplicity of the Viola-Seaborg approach [41]. In 2019, Chen et al. modified the GLM to consider the screening effect of the Coulomb interaction between the emitted proton and daughter nuclei on Hulthen potential [24]. In 2021, Liu et al. [60] applied the GLM to two-proton radioactivity research. Subsequently, in 2022, Zhu et al. [61] investigated two-proton radioactivity using the GLM, considering electrostatic screening effects. More recently, in 2024, Zhang et al. [62] developed the deformed Gamow-like model (D-GLM-zhang) to examine how angular momentum affects the half-life of proton radioactivity. Insights into the final Nilsson configuration, and consequently, valuable information about nuclear shape, are provided by studying the half-life associated with proton radioactivity in deformed nuclei. This paper modified the Coulomb interaction between the emitted proton and daughter nucleus by considering the deformation effect of the daughter nucleus and systematically calculated the half-lives of single-proton and two-proton radioactive nuclei.The remainder of this article is organized as follows: Sec. II discusses the theoretical framework of the computational model in detail, Sec. III presents and discusses the results, and Sec. IV summarizes the findings.

-

Proton radioactivity, discovered as a significant spontaneous decay mode in the study of exotic nuclei beyond the

$ \beta $ -stability line, manifests as single-proton and two-proton (2p) radioactivity. First detected by Jackson et al. during the 1970s in the isomeric state of 53Com [1, 2], it was later independently observed from ground states in 151Lu [3] (by Hofmann) and 147Tm [4] (by Klepper). Following these key findings, numerous proton-emitting radionuclides have been identified. To date, research has characterized over 40 such emitters in ground and isomeric states across the Z=51~83 region. Although proton radioactivity exists in nuclei with Z<50, accurately measuring their extremely short half-lives remains challenging because of current limitations in experimental techniques and detection equipment [5]. The phenomenon of true two-proton radioactivity (requiring$ Q_{\rm{2p}} > $ 0 and$ Q_{\rm{p} } < $ 0, where$ Q_{\rm{p}} $ and$ Q_{\rm{2p}} $ represent the single-proton radioactivity released energy and two-proton radioactivity released energy) was first established theoretically by Zel'dovich and Goldansky in the 1960s [6−8]. It was initially observed experimentally in 45Fe at GSI and GANIL in 2002 [9, 10]. Since then, this decay mode has been found in other neutron-deficient nuclei, specifically 54Zn, 48Ni, 19Mg, and 67Kr [11−14]. Before 2002, the not true 2p radioactivity ($ Q_{\rm{2p}} > $ 0 and$ Q_{\rm{p}} > $ 0) was observed from 6Be, 12O, and 16Ne [15−20]. The exploration of nuclear structure and potential proton drip line [21−26] is anticipated to advance through the discovery of more proton-emitting radionuclides, facilitated by upgrades to experimental facilities and methods. As a valuable tool for investigating nuclear properties such as released energy and half-life, proton radioactivity is becoming an increasingly important topic in the field [27−30].Numerous empirical formulas and theoretical models have been developed to study the half-life of proton radioactivity. In the field of single-proton radioactivity, these include the single-folding model [31, 32], generalized liquid drop model (GLDM) [33], relativistic density functional theory [34], density-dependent M3Y effective interactions [35, 36], phenomenological unified fission model [37, 38], distorted-wave Born approximation [39], universal decay law of proton radioactivity (UDLP) [40], Gamow-like model (GLM) [24, 41], Coulomb and proximity potential model (CPPM) [42], deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum [43], and triaxial relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum [44], among others. In the field of two-proton radioactivity, these include the direct decay model [45−49], the simultaneous versus sequential decay model [7, 50], diproton model [8, 51], and three-body model, among others [49, 52−55]. Furthermore, empirical formulas serve as critical analytical tools in two-proton emission studies, and they are predominantly derived from the Geiger-Nuttall (G-N) law [56]. Representative formulations include those proposed by Sreeja et al. [57] and Liu et al. [58].

The GLM, a simple phenomenological model, was initially proposed by Zdeb et al. to study

$ \alpha $ decay [59]. The calculated$ \alpha $ decay half-life of the model showed close agreement with experimental values, prompting its extension to proton radioactivity investigation [41]. In this application, the GLM demonstrated high sensitivity of proton radioactivity half-lives to the external barrier position, emphasizing that accurate potential energy curves are vital in calculations. The GLM represents the external potential via the Coulomb and centrifugal potentials and the internal potential as a square well potential. This method has considerably deeper physical foundations and retains the simplicity of the Viola-Seaborg approach [41]. In 2019, Chen et al. modified the GLM to consider the screening effect of the Coulomb interaction between the emitted proton and daughter nuclei on Hulthen potential [24]. In 2021, Liu et al. [60] applied the GLM to two-proton radioactivity research. Subsequently, in 2022, Zhu et al. [61] investigated two-proton radioactivity using the GLM, considering electrostatic screening effects. More recently, in 2024, Zhang et al. [62] developed the deformed Gamow-like model (D-GLM-zhang) to examine how angular momentum affects the half-life of proton radioactivity. Insights into the final Nilsson configuration, and consequently, valuable information about nuclear shape, are provided by studying the half-life associated with proton radioactivity in deformed nuclei. This paper modified the Coulomb interaction between the emitted proton and daughter nucleus by considering the deformation effect of the daughter nucleus and systematically calculated the half-lives of single-proton and two-proton radioactive nuclei.The remainder of this article is organized as follows: Sec. II discusses the theoretical framework of the computational model in detail, Sec. III presents and discusses the results, and Sec. IV summarizes the findings.

-

In the DGLM model, the half-life and decay constant of the proton radioactivity are related as

$ T_{1/2}=\frac{\ln 2}{\lambda _{\rm{p/2p}}}, $

(1) where the decay constant

$ \lambda _{\rm{p/2p}} $ is defined as$ \lambda _{\rm{p/2p}}=S_{\rm{p/2p}}\nu P. $

(2) where

$ S_{\rm{p/2p}} $ represents the spectroscopic factor for either single-proton or two-proton radioactive systems,$ P $ represents the barrier penetration probability of the proton, and$ \nu $ represents its collision frequency with the potential barrier.When deformation effects are considered, the radius

$ R_{\rm{in}} $ and Coulomb potential$ V_{\rm{c}} $ of the square well change. Consequently, the total penetration probability is calculated by averaging over all directions as$ P=\frac{1}{2}\int_{0}^{\pi }P_{\theta }\sin \theta \,{\rm d}\theta, $

(3) where

$ \theta $ represents the angle between the subnucleus symmetry axis and radial vector. Under the classical Wentzel-Kramers-Brillouin approximation, this directional penetration probability takes the form$ P_{\theta }=\exp \left[ -\frac{2}{\hbar }\int_{R_{\rm{in}}(\theta )}^{R_{ \mathrm{out}}(\theta )}\sqrt{2\mu |V(r,\theta )-E_{k}|}\,{\rm d}r\right], $

(4) where

$ R_{\rm{in}}(\theta ) $ and$ R_{\rm{out}}(\theta ) $ represent the positions of the inner and outer barriers, respectively. The position$ R_{\rm{out}} $ of the outer barrier is derived from the equation$ V(R_{\rm{out}}(\theta ))=E_{k} $ .$ \mu =\frac{m_{\rm{p/2p}}m_{\rm{d}}}{m_{\rm{p/2p}}+m_{\rm{d}}}\approx 938.3\times A_{\rm{p/2p}}\times \frac{A_{\rm{d}}}{A} \text{ MeV/c}^{2} $ represents the reduced mass, where$ m_{\rm{p/2p}} $ and$ m_{\rm{d}} $ represent the masses of the emitted proton and daughter nuclei, respectively. Further,$ A_{\rm{p/2p}} $ ,$ A_{\rm{d}} $ , and$ A $ represent the mass numbers of the emitted proton, daughter nuclei, and proton emitter, respectively. In addition,$ E_{k}= Q_{\rm{p/2p}}(A- A_{\rm{p/2p}})/A $ represents the kinetic energy of the emitted proton. Incorporating electrostatic screening modifies$ Q_{\rm{p/2p}} $ , which is given by$ Q_{\rm{p/2p}}=\Delta M-(\Delta M_{\rm{d}}+\Delta M_{\rm{p/2p} })+k(Z^{\varepsilon }-Z_{\rm{d}}^{\varepsilon }), $

(5) where Z and

$ Z_{\rm{d}} $ represent the number of protons in the parent and daughter nuclei, respectively.$ \Delta M $ ,$ \Delta M_{\rm{d}} $ , and$ \Delta M_{\rm{p/2p}} $ represent the mass excesses of the parent nucleus, daughter nucleus, and emitted proton, respectively. The term$ k(Z^{\varepsilon }-Z_{\rm{d}}^{\varepsilon }) $ represents the charge screening effect where$ k=8.7$ eV,$ \varepsilon =2.517 $ for$ Z\geq 60 $ and$ k=13.6$ eV,$ \varepsilon =2.408 $ for$ Z<60 $ [63, 64].Summing the daughter nucleus radius and emitted proton radius yields the internal barrier position

$ R_{\rm{in}}(\theta ) $ .$ R_{\rm{in}}(\theta )=R_{\rm{p/2p}}+R_{\rm{d}}(\theta ), $

(6) $ R_{\rm{p/2p}}=r_{0}A_{\rm{p/2p}}^{1/3} $ represents the radius of the emitted proton, where$ A_{\rm{p/2p}} $ represents the mass number of the emitted proton.$ r_{0} $ represents the effective nuclear radius constant and is the only adjustable parameter in this model. Considering the effect of the deformation of the daughter nucleus, the radius is expressed as$ R_{\rm{d}}(\theta )=r_{0}A_{\rm{d}}^{1/3}\left[ 1+\sum\limits_{\lambda }\beta _{\lambda }Y_{\lambda 0}(\theta )\right], $

(7) where

$ \beta _{\lambda } $ represents the deformation parameter of the daughter nucleus ($ \lambda =2,4,6 $ correspond to the quadrupole, hexadecapole, and hexacontatetrapole deformations) and$ \beta _{\lambda } $ values are taken from FRDM2012 [65].$ Y_{\lambda 0}(\theta ) $ represents the spherical harmonics function.The total interaction potential

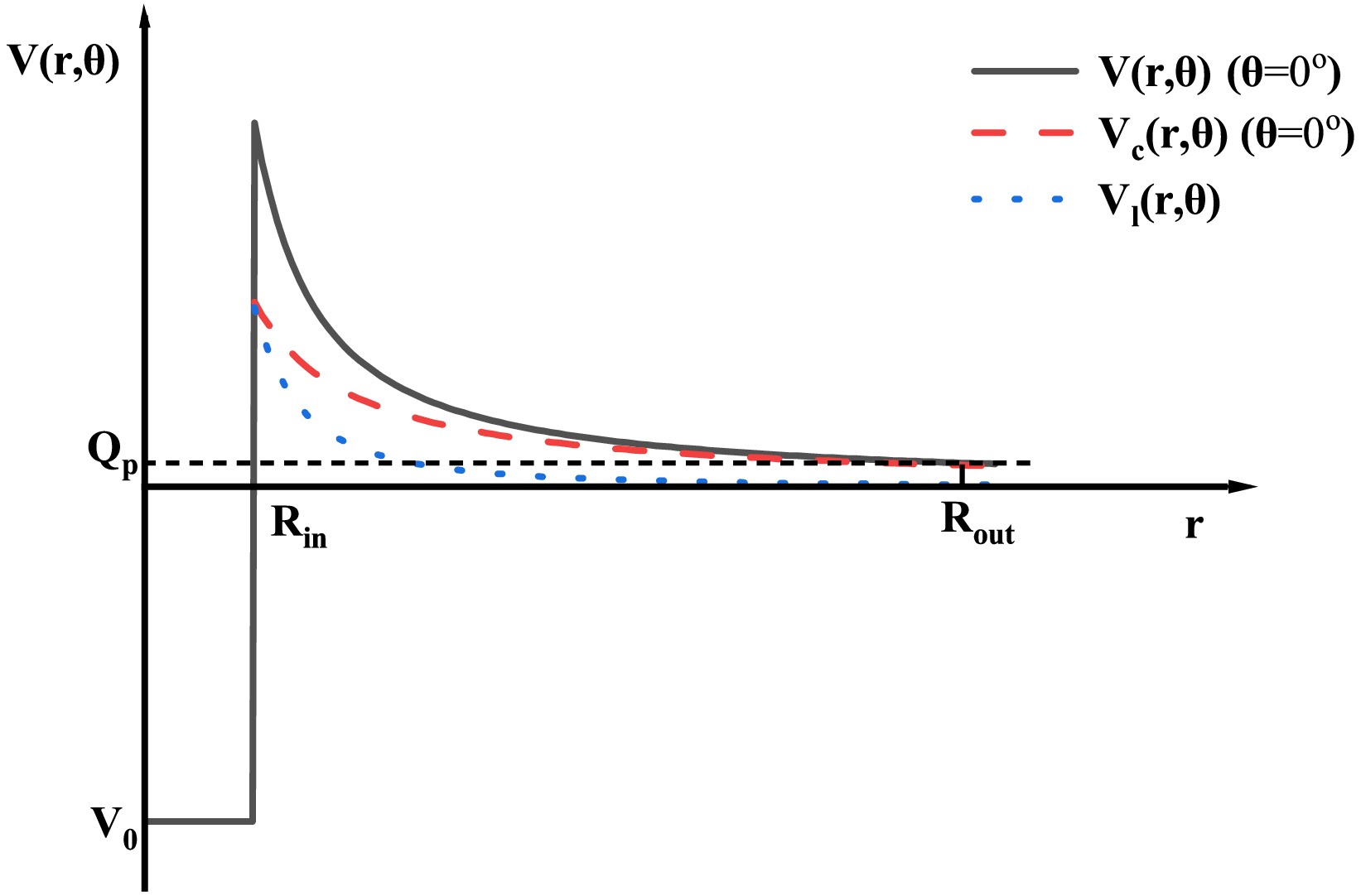

$ V(r,\theta ) $ between the daughter nucleus and the emitted proton can be expressed as$ V(r,\theta )= \begin{cases} -V_{0}, & 0\leq r\leq R_{\rm{in}}, \\ V_{\rm{c}}(r,\theta )+V_{l}(r), & r>R_{\rm{in}} \end{cases} $

(8) where

$ V_{0} $ represents the depth of the inner square well,$ V_{0}=25A_{\rm{p/2p}}$ MeV [66].$ V_{\rm{c}} $ represents the Coulomb interaction between the daughter nucleus and the emitted proton. Considering the effect of the deformation of the daughter nucleus on the Coulomb potential, the expression for the Coulomb potential is derived as$ \begin{aligned}[b] V_{\rm{c}}(r,\theta ) =\;&\frac{Z_{\rm{d}}Z_{\rm{p/2p}}{\rm{e}}^{2}}{r}+ \frac{3Z_{\rm{d}}Z_{\rm{p/2p}}{\rm{e}}^{2}}{r}\sum\limits_{\lambda =2,4,6}\frac{ 1}{2\lambda +1} \\ & \times \lbrack \frac{R_{\rm{d}}(\theta )}{r}]^{\lambda }Y_{\lambda 0}(\theta )\beta _{\lambda }, \end{aligned} $

(9) where r represents the distance between the daughter nucleus and the emitting proton. The centrifugal potential energy term is expressed as

$ V_{l}(r)=\frac{\hbar ^{2}l(l+1)}{2\mu r^{2}}, $

(10) where l represents the angular momentum carried by the emitted proton and determined by the spin parity conservation law. It can be expressed as [67]

$ l= \begin{cases} \Delta _{j} & {\rm{for\ even}}\; \Delta _{j}\; {\rm{and}}\; \pi =\pi _{\rm{d}}, \\ \Delta _{j}+1 & {\rm{for\ even}}\; \Delta _{j}\; {\rm{and}}\;\pi \neq \pi _{\rm{d}}, \\ \Delta _{j} & {\rm{for\ odd}}\; \Delta _{j}\; {\rm{and}}\; \pi \neq \pi _{\rm{d }}, \\ \Delta _{j}+1 & {\rm{for\ odd}}\; \Delta _{j}\; {\rm{and}}\; \pi =\pi _{\rm{d} }, \end{cases} $

(11) where

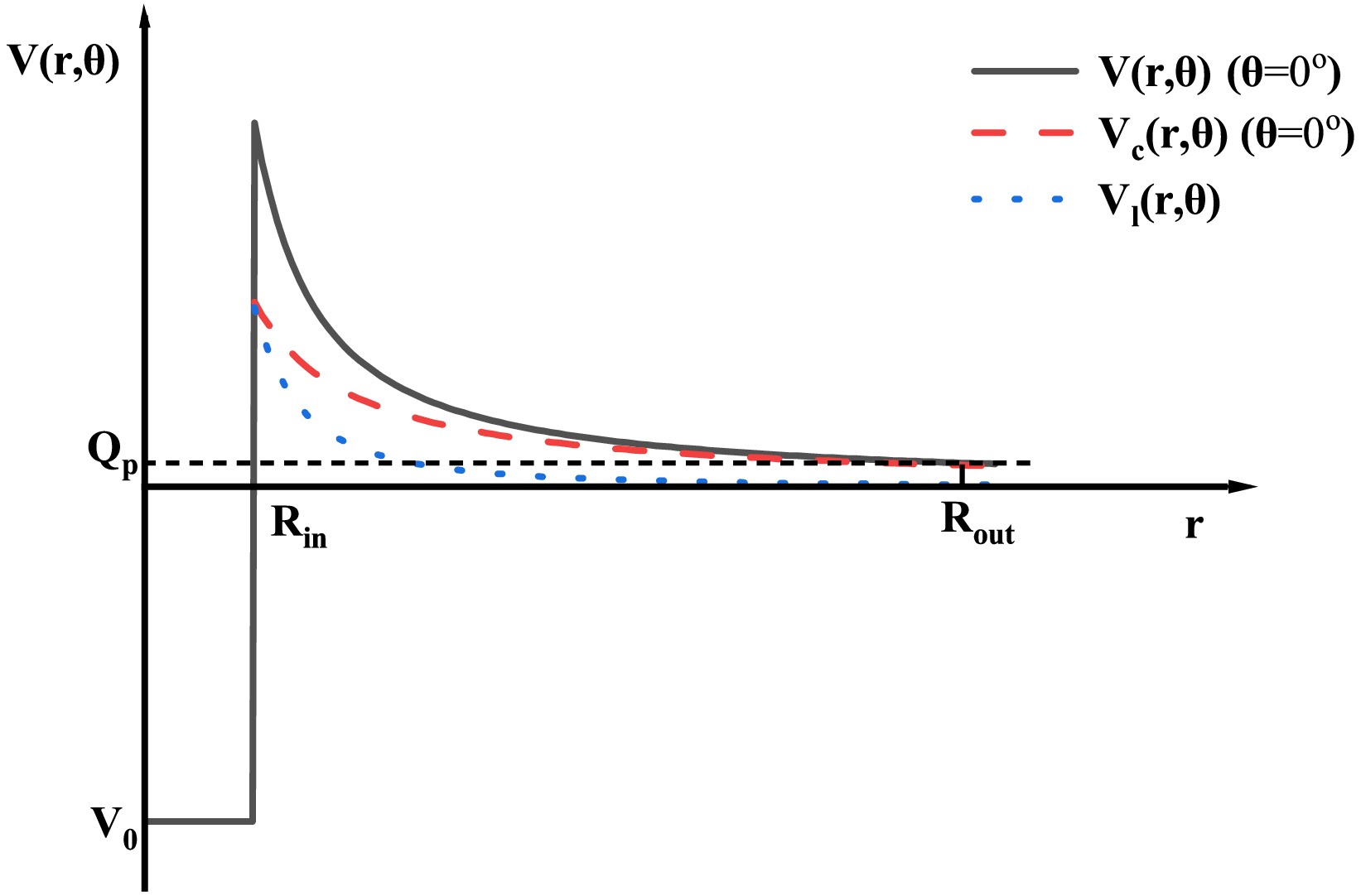

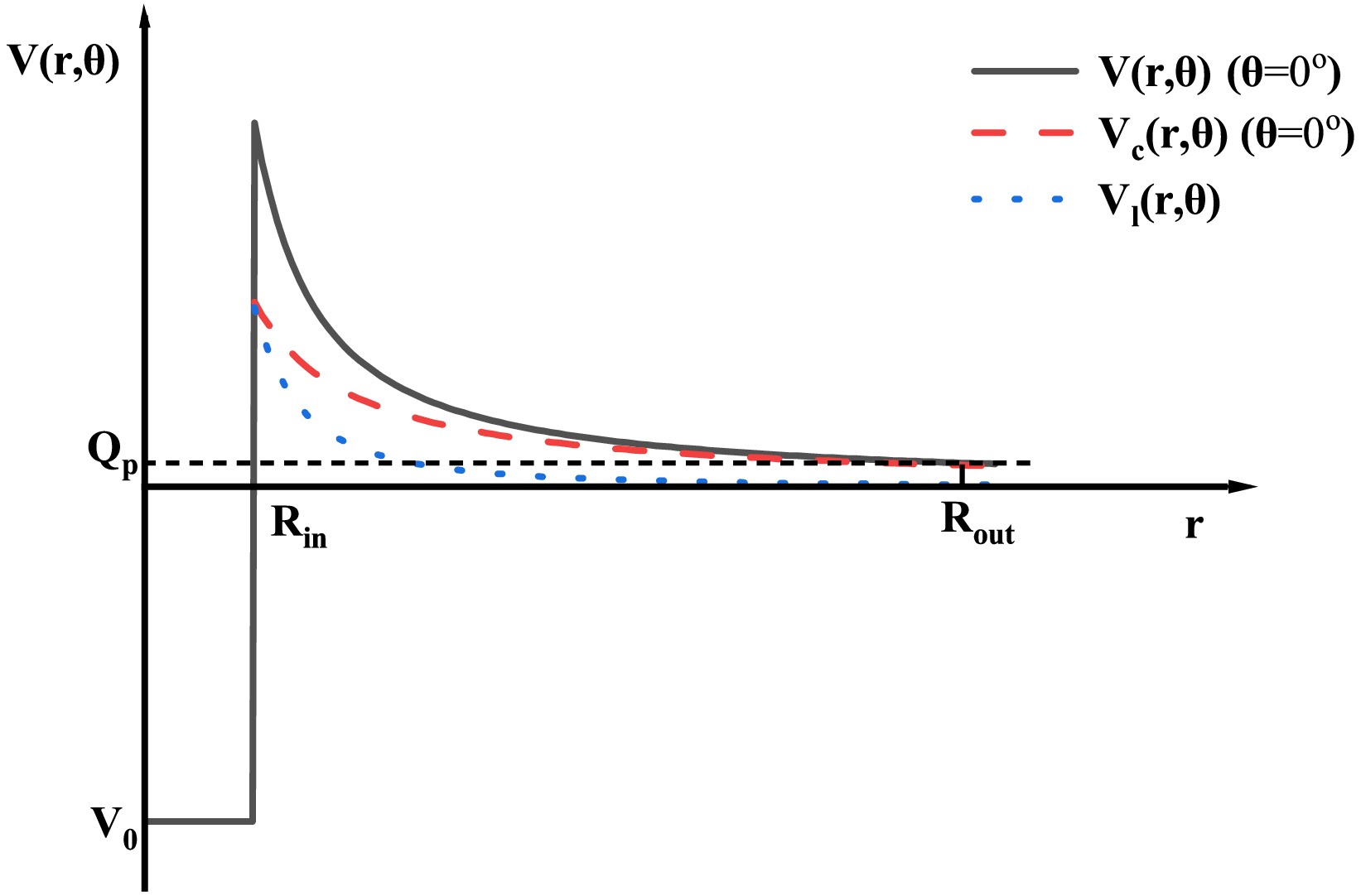

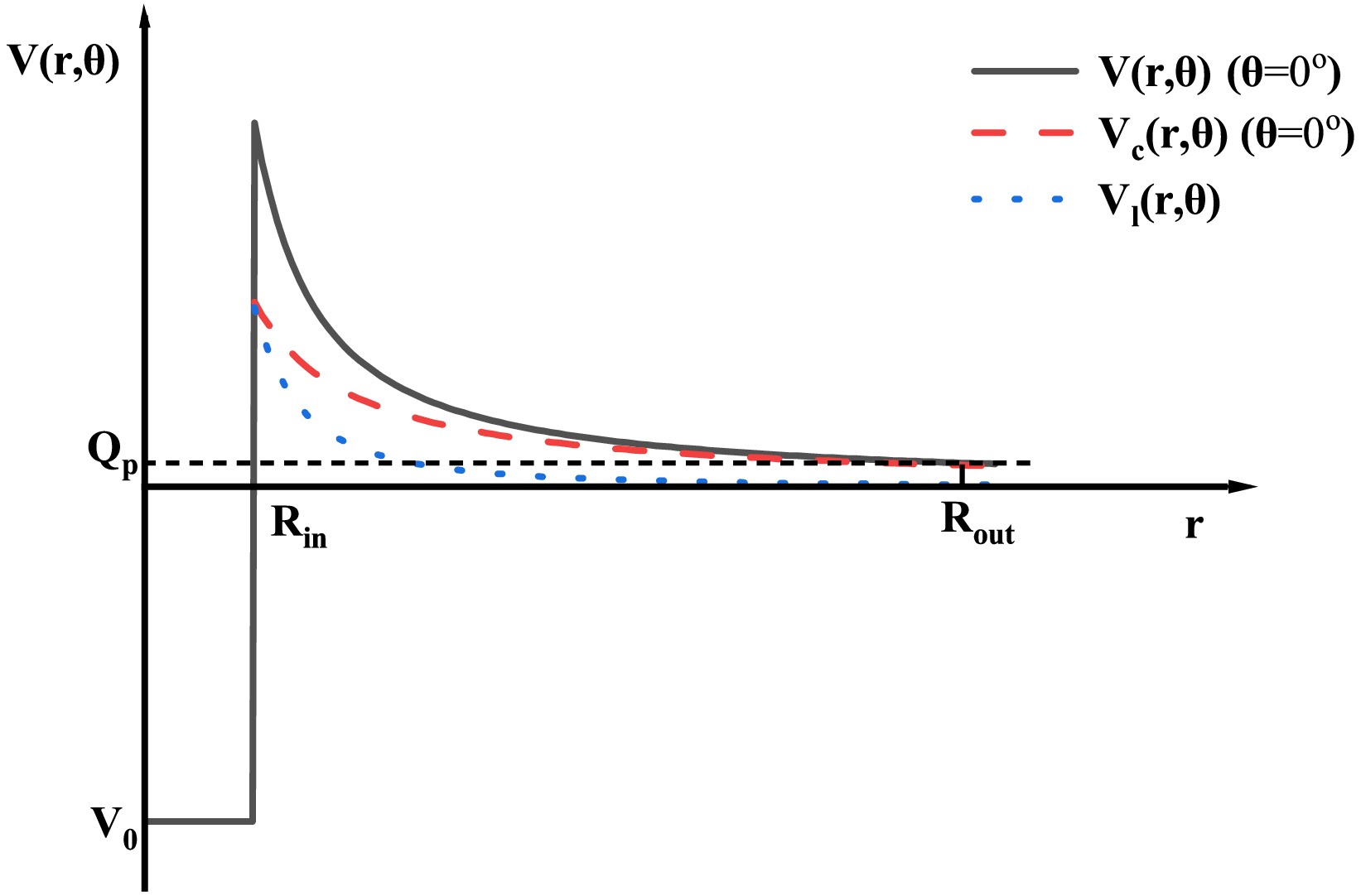

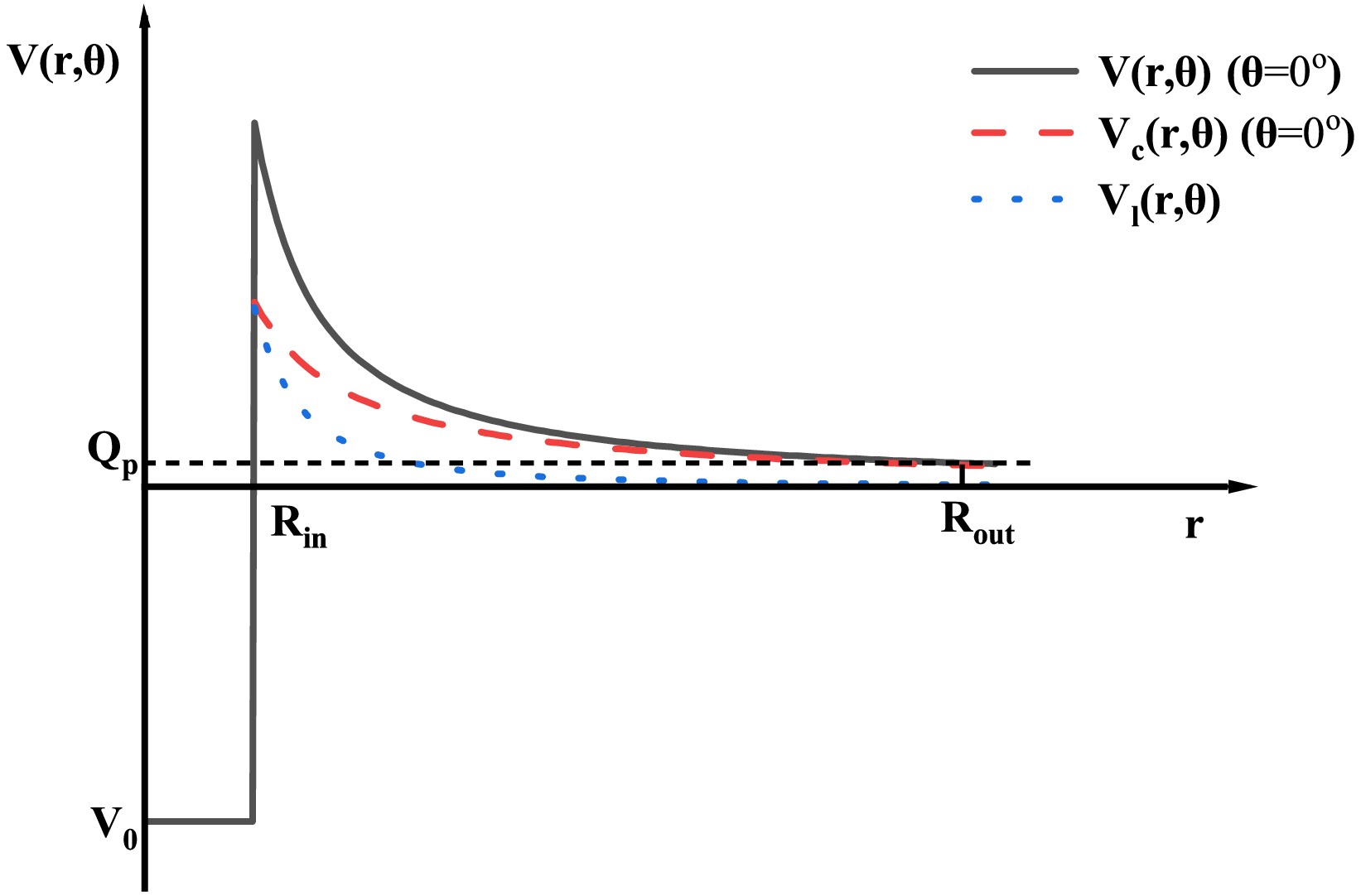

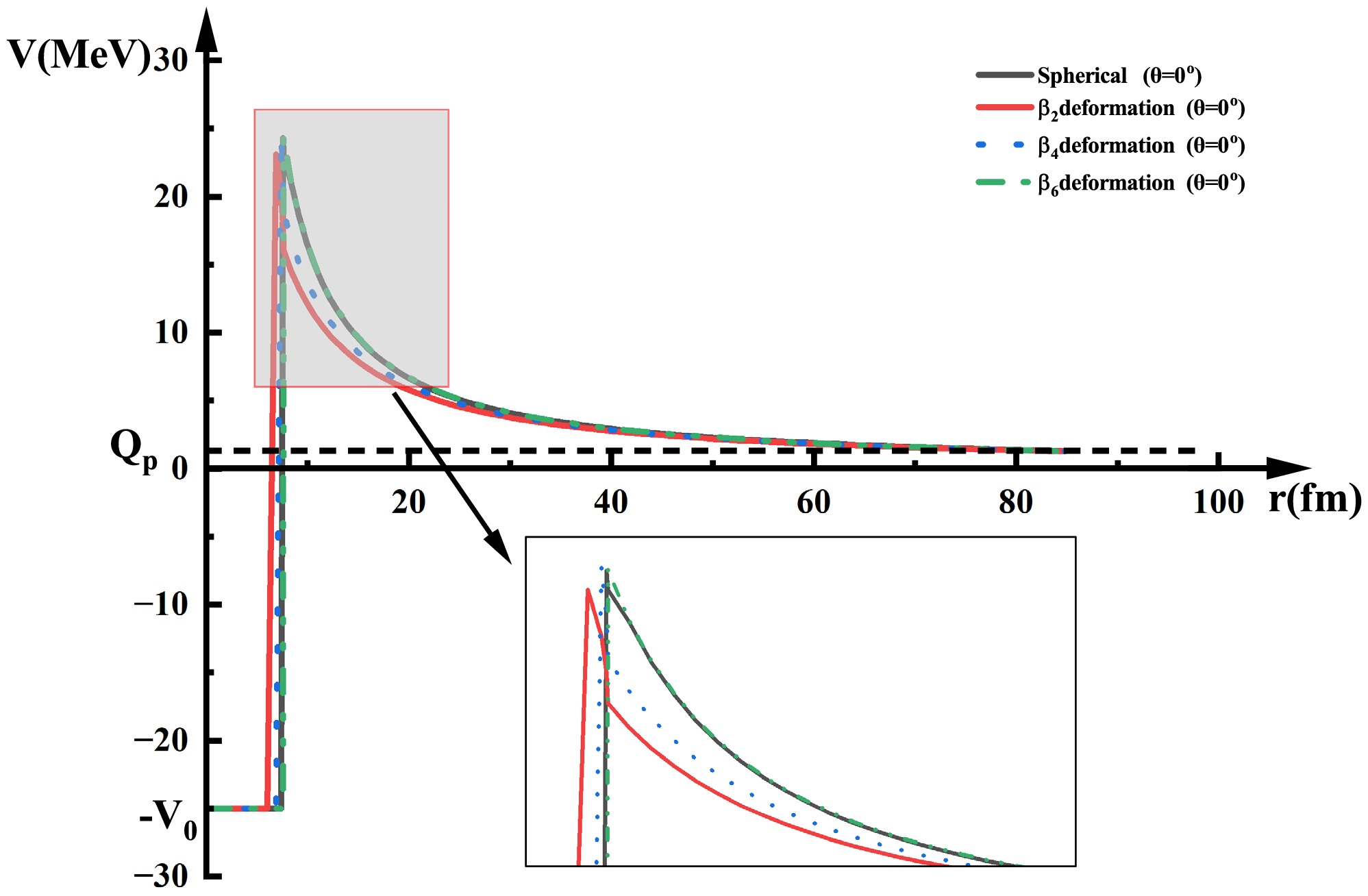

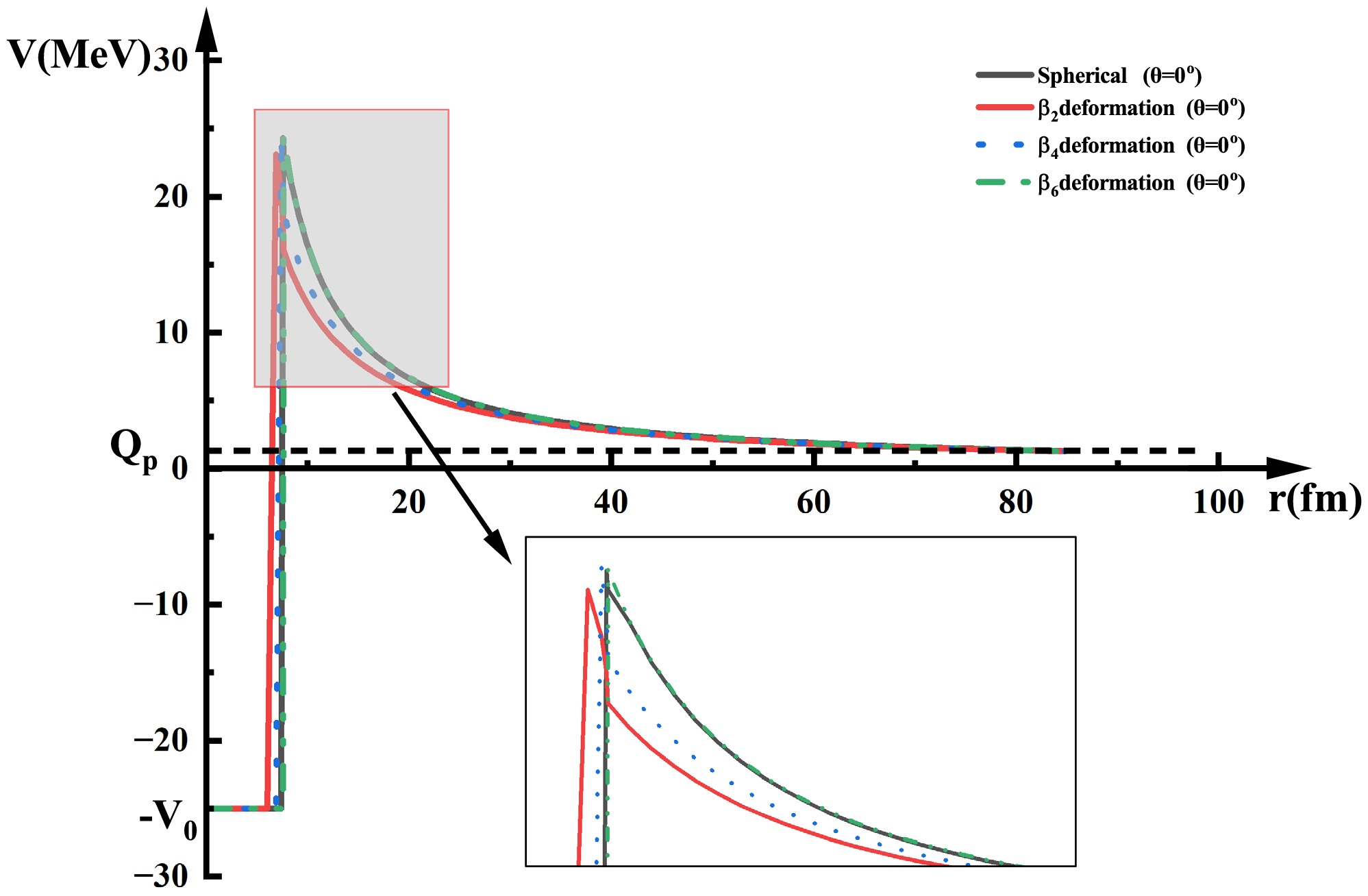

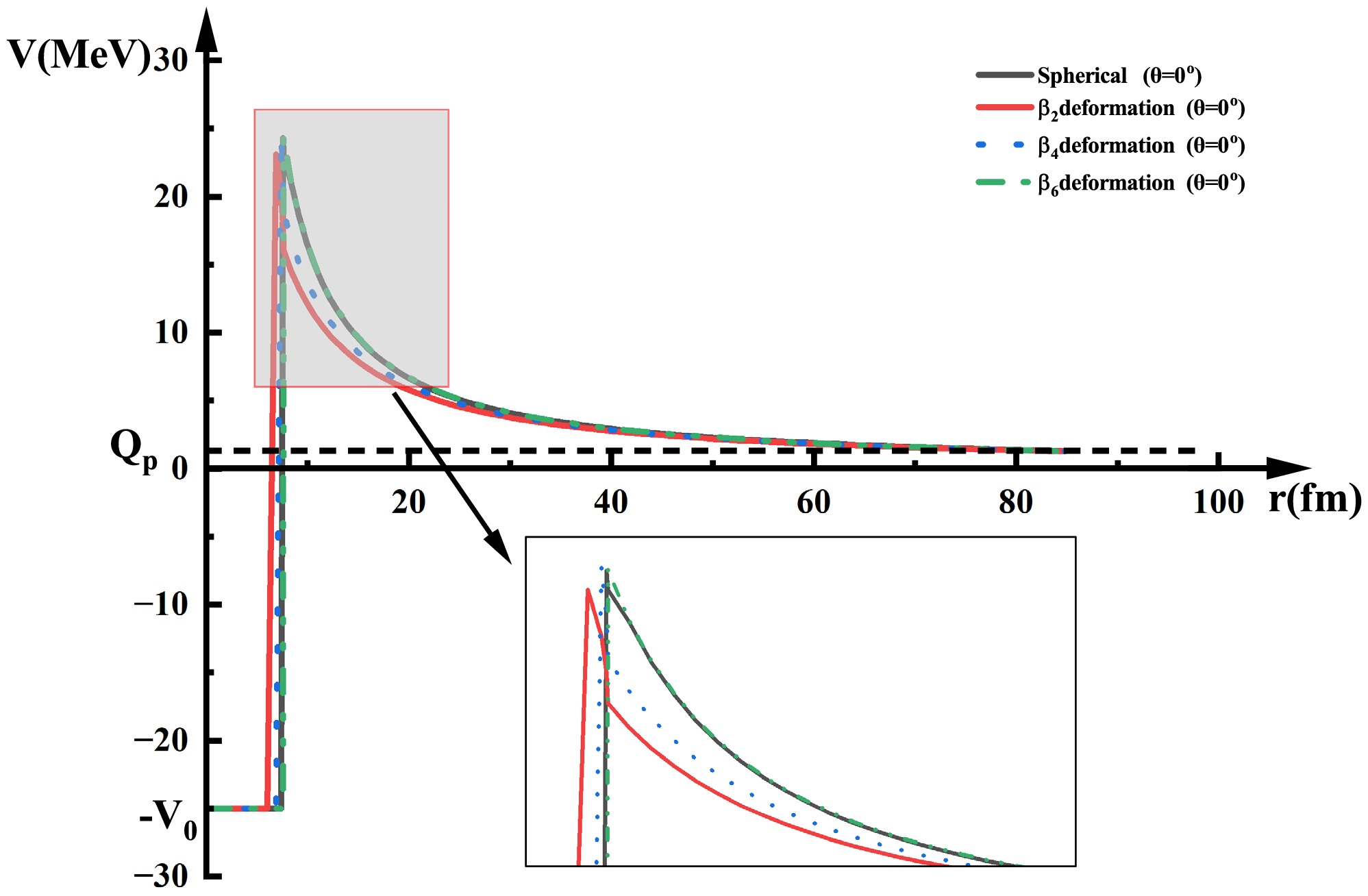

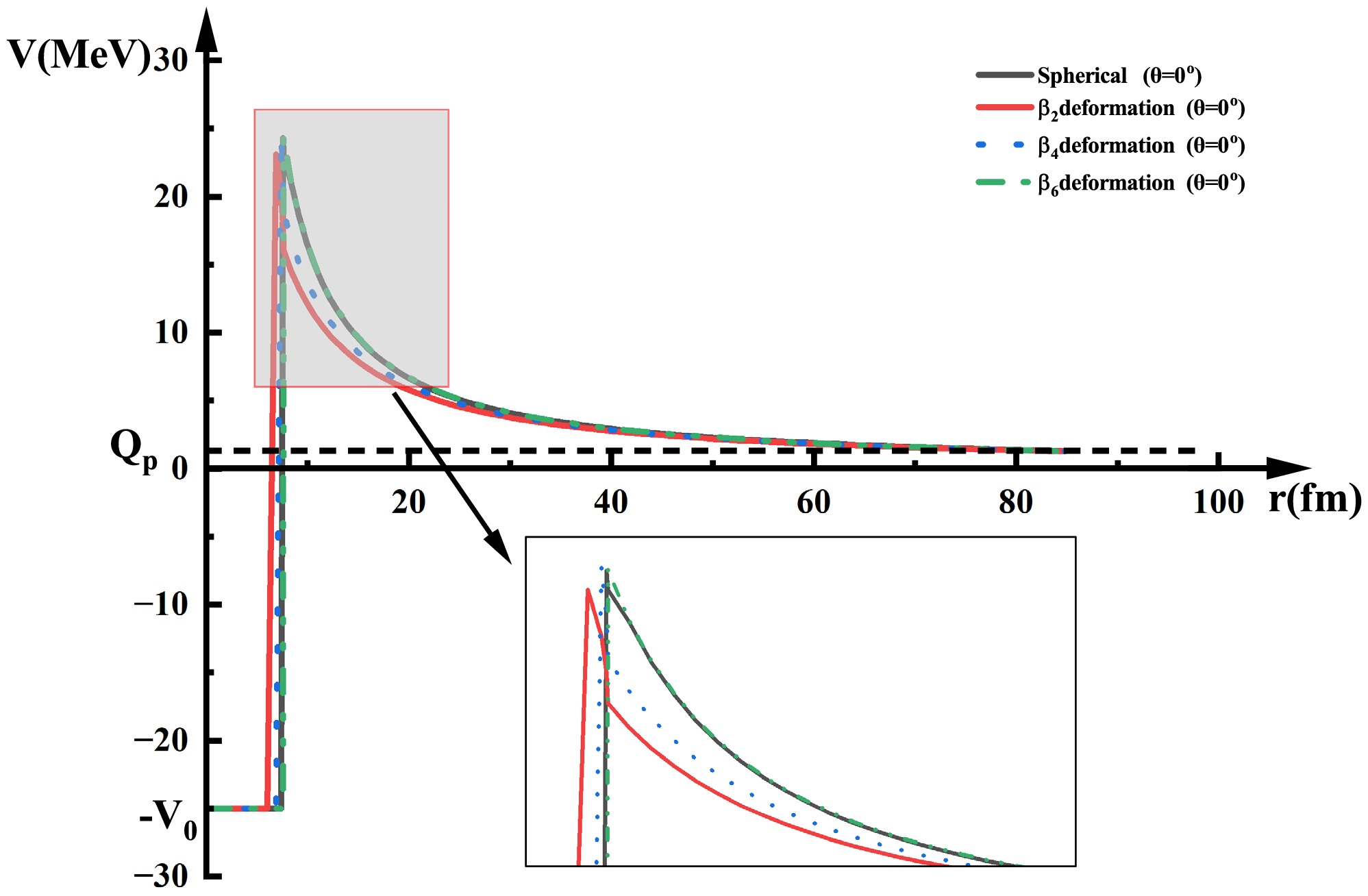

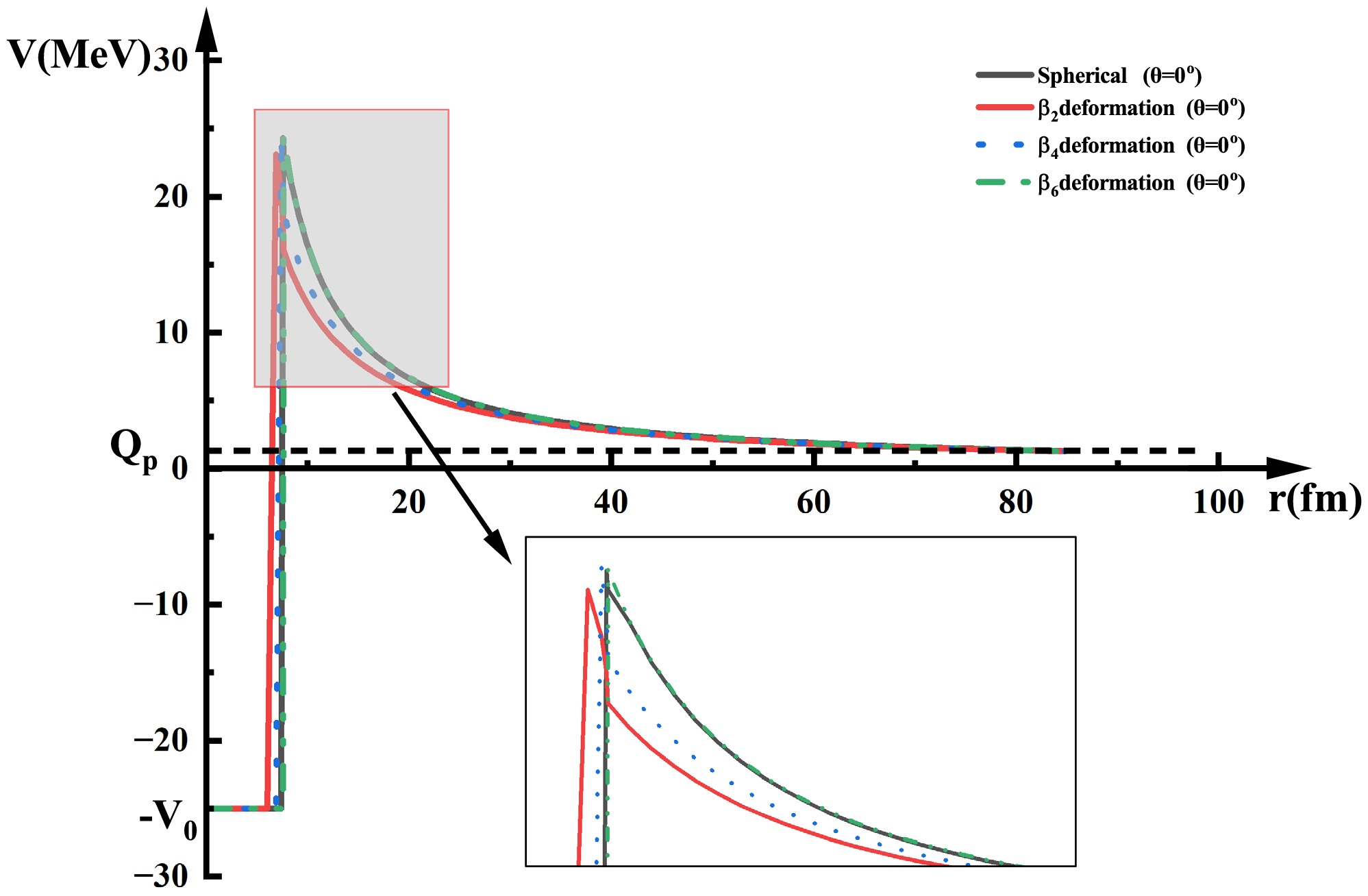

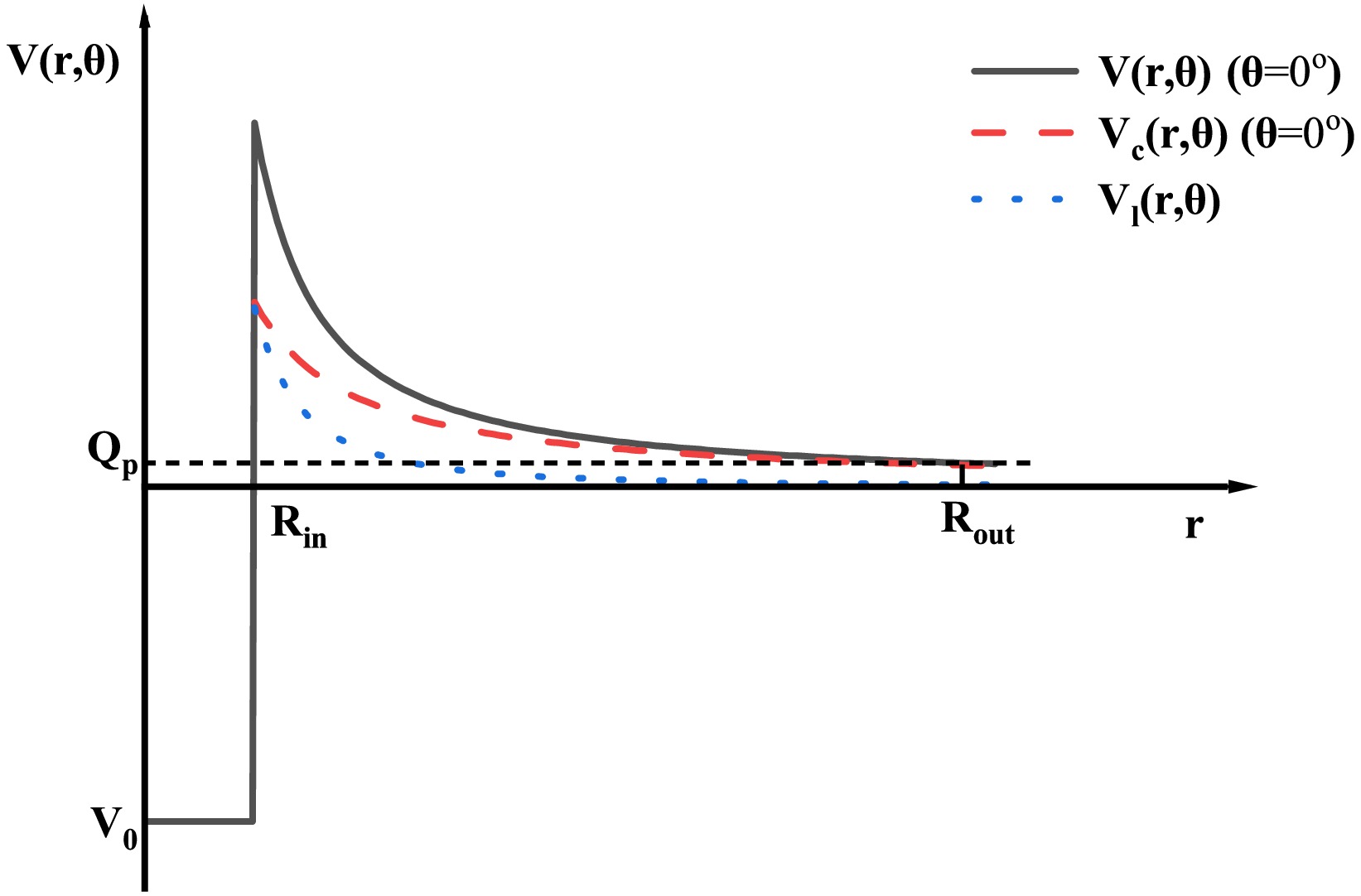

$ \pi $ and$ \pi _{\rm{d}} $ represent the parity of the parent and daughter nuclei, respectively.$ \Delta _{j}=|j-j_{\rm{d}}-j_{\rm{p}}^{\prime }| $ with$ j $ ,$ j_{\rm{d}} $ , and$ j_{\rm{p}}^{\prime } $ being the spins of the parent nucleus and emitted proton (for proton$ j^{\pi }=(1/2)^{+} $ ), respectively. We show the distribution of barriers in Fig. 1. In the first approximation, it is assumed to be given by the harmonic oscillator frequency in the Nilsson potential [68].

Figure 1. (color online) Relationship between the potential energy and center of mass distance of the decay system for 144Tm. The red and blue curves represent the Coulomb potential and centrifugal potential, respectively.

$ h\nu =\hbar \omega \simeq \frac{41}{A^{1/3}}{\rm{MeV}}, $

(12) where

$ h $ ,$ \hbar $ ,$ \omega $ , and$ A $ represent the Planck constant, reduced Planck constant, angular frequency, and mass number of proton emitters, respectively. -

In the DGLM model, proton radioactivity's half-life and decay constant are related as follows:

$ T_{1/2}=\frac{\ln 2}{\lambda _{\rm{p/2p}}}, $

(1) where the decay constant

$ \lambda _{\rm{p/2p}} $ is defined as:$ \lambda _{\rm{p/2p}}=S_{\rm{p/2p}}\nu P. $

(2) Here,

$ S_{\rm{p/2p}} $ represents the spectral factor for either single-proton or two-proton radioactive systems;$ P $ denotes the proton's barrier penetration probability, while$ \nu $ is its collision frequency with the potential barrier.When deformation effects are considered, both the radius

$ R_{\rm{in}} $ and Coulomb potential$ V_{\rm{c}} $ of the square well change. Consequently, the total penetration probability is calculated by averaging over all directions:$ P=\frac{1}{2}\int_{0}^{\pi }P_{\theta }\sin \theta \,d\theta $

(3) where

$ \theta $ denotes the angle between the subnucleus symmetry axis and the radial vector. Under the classical WKB (Wentzel-Kramers-Brillouin) approximation, this directional penetration probability takes the form:$ P_{\theta }=\exp \left[ -\frac{2}{\hbar }\int_{R_{\rm{in}}(\theta )}^{R_{ \mathrm{out}}(\theta )}\sqrt{2\mu |V(r,\theta )-E_{k}|}\,dr\right] $

(4) where

$ R_{\rm{in}}(\theta ) $ and$ R_{\rm{out}}(\theta ) $ are the positions of the inner and outer barriers. The position$ R_{\rm{out}} $ of the outer barrier is derived from the equation$ V(R_{\rm{out}}(\theta ))=E_{k} $ .$ \mu =\frac{m_{\rm{p/2p}}m_{\rm{d}}}{m_{\rm{p/2p}}+m_{\rm{d}}}\approx 938.3\times A_{\rm{p/2p}}\times \frac{A_{\rm{d}}}{A} \text{ MeV/c}^{2} $ is the reduced mass, where$ m_{\rm{p/2p}} $ and$ m_{\rm{d}} $ are the masses of the emitted proton and the daughter nuclei, respectively.$ A_{\rm{p/2p}} $ ,$ A_{\rm{d}} $ , and$ A $ are the mass numbers of the emitted proton, the daughter nuclei, and proton emitter, respectively. In addition,$ E_{k}=Q_{\rm{p/2p}}(A-A_{\rm{p/2p}})/A $ denotes the kinetic energy of emitted proton. Incorporating electrostatic shielding modifies$ Q_{\rm{p/2p}} $ , which is given by:$ Q_{\rm{p/2p}}=\Delta M-(\Delta M_{\rm{d}}+\Delta M_{\rm{p/2p} })+k(Z^{\varepsilon }-Z_{\rm{d}}^{\varepsilon }) $

(5) where Z and

$ Z_{\rm{d}} $ are the number of protons in the parent and daughter nuclei, respectively.$ \Delta M $ ,$ \Delta M_{\rm{d}} $ , and$ \Delta M_{\rm{p/2p}} $ are the mass excesses of the parent nucleus, daughter nucleus, and the emitted proton, respectively. The term$ k(Z^{\varepsilon }-Z_{\rm{d}}^{\varepsilon }) $ denotes the charge shielding effect, where$ k=8.7$ eV,$ \varepsilon =2.517 $ for$ Z\geq 60 $ , and$ k=13.6$ eV,$ \varepsilon =2.408 $ for$ Z<60 $ [71, 72].Summing the daughter nucleus radius and emitted proton radius yields the internal barrier position

$ R_{\rm{in}}(\theta ) $ :$ R_{\rm{in}}(\theta )=R_{\rm{p/2p}}+R_{\rm{d}}(\theta ) $

(6) $ R_{\rm{p/2p}}=r_{0}A_{\rm{p/2p}}^{1/3} $ is the radius of the emitted proton, where$ A_{\rm{p/2p}} $ represents the mass number of the emitted proton.$ r_{0} $ is the effective nuclear radius constant and is the only adjustable parameter in this model. Considering the influence of the deformation of the daughter nucleus, the radius is expressed as:$ R_{\rm{d}}(\theta )=r_{0}A_{\rm{d}}^{1/3}\left[ 1+\sum\limits_{\lambda }\beta _{\lambda }Y_{\lambda 0}(\theta )\right] $

(7) where

$ \beta _{\lambda } $ is the deformation parameter of the daughter nucleus ($ \lambda =2,4,6 $ correspond to the quadrupole, hexadecapole, and hexacontatetrapole deformations) and$ \beta _{\lambda } $ values are taken from FRDM2012 [73].$ Y_{\lambda 0}(\theta ) $ is the spherical harmonics function.The total interaction potential

$ V(r,\theta ) $ between the daughter nucleus and the emitted proton can be expressed as:$ V(r,\theta )= \begin{cases} -V_{0}, & 0\leq r\leq R_{\rm{in}}, \\ V_{\rm{c}}(r,\theta )+V_{l}(r), & r>R_{\rm{in}} \end{cases} $

(8) where

$ V_{0} $ represents the depth of the inner square well,$ V_{0}=25A_{\rm{p/2p}}$ MeV [74].$ V_{\rm{c}} $ denotes the Coulomb interaction between the daughter nucleus and the emitted proton. Taking into account the impact of the deformation of the daughter nucleus on the Coulomb potential, the expression for the Coulomb potential is derived as follows:$ \begin{aligned}[b] V_{\rm{c}}(r,\theta ) =\;&\frac{Z_{\rm{d}}Z_{\rm{p/2p}}{\rm{e}}^{2}}{r}+ \frac{3Z_{\rm{d}}Z_{\rm{p/2p}}{\rm{e}}^{2}}{r}\sum\limits_{\lambda =2,4,6}\frac{ 1}{2\lambda +1} \\ & \times \lbrack \frac{R_{\rm{d}}(\theta )}{r}]^{\lambda }Y_{\lambda 0}(\theta )\beta _{\lambda }, \end{aligned} $

(9) where r is the distance between the daughter nucleus and the emitting proton. The centrifugal potential energy term is expressed as:

$ V_{l}(r)=\frac{\hbar ^{2}l(l+1)}{2\mu r^{2}}, $

(10) where l is the angular momentum carried by the emitted proton, determined by the spin parity conservation law. It can be expressed as [75]:

$ l= \begin{cases} \Delta _{j} & {\rm{for\ even}}\,\Delta _{j}\,{\rm{and}}\,\pi =\pi _{\rm{d}}, \\ \Delta _{j}+1 & {\rm{for\ even}}\,\Delta _{j}\,{\rm{and}}\,\pi \neq \pi _{\rm{d}}, \\ \Delta _{j} & {\rm{for\ odd}}\,\Delta _{j}\,{\rm{and}}\,\pi \neq \pi _{\rm{d }}, \\ \Delta _{j}+1 & {\rm{for\ odd}}\,\Delta _{j}\,{\rm{and}}\,\pi =\pi _{\rm{d} }, \end{cases} $

(11) where

$ \pi $ and$ \pi _{\rm{d}} $ are the parity of the parent and daughter nuclei, respectively.$ \Delta _{j}=|j-j_{\rm{d}}-j_{\rm{p}}^{\prime }| $ with$ j $ ,$ j_{\rm{d}} $ , and$ j_{\rm{p}}^{\prime } $ being the spins of the parent nucleon and the emitted proton (for proton$ j^{\pi }=(1/2)^{+} $ ), respectively. We show the distribution of barriers in Figure 1. In the first approximation, it is assumed to be given by the harmonic oscillator frequency in the Nilsson potential [76]:

Figure 1. (Color online) The relationship between the potential energy and the decay system's center of mass distance for 144Tm. The red and blue curves represent the Coulomb potential and the centrifugal potential, respectively.

$ h\nu =\hbar \omega \simeq \frac{41}{A^{1/3}}{\rm{MeV}}, $

(12) where

$ h $ ,$ \hbar $ ,$ \omega $ , and$ A $ represent the Planck constant, reduced Planck constant, angular frequency, and mass number of proton emitters, respectively. -

In the DGLM model, the half-life and decay constant of the proton radioactivity are related as

$ T_{1/2}=\frac{\ln 2}{\lambda _{\rm{p/2p}}}, $

(1) where the decay constant

$ \lambda _{\rm{p/2p}} $ is defined as$ \lambda _{\rm{p/2p}}=S_{\rm{p/2p}}\nu P. $

(2) where

$ S_{\rm{p/2p}} $ represents the spectroscopic factor for either single-proton or two-proton radioactive systems,$ P $ represents the barrier penetration probability of the proton, and$ \nu $ represents its collision frequency with the potential barrier.When deformation effects are considered, the radius

$ R_{\rm{in}} $ and Coulomb potential$ V_{\rm{c}} $ of the square well change. Consequently, the total penetration probability is calculated by averaging over all directions as$ P=\frac{1}{2}\int_{0}^{\pi }P_{\theta }\sin \theta \,{\rm d}\theta, $

(3) where

$ \theta $ represents the angle between the subnucleus symmetry axis and radial vector. Under the classical Wentzel-Kramers-Brillouin approximation, this directional penetration probability takes the form$ P_{\theta }=\exp \left[ -\frac{2}{\hbar }\int_{R_{\rm{in}}(\theta )}^{R_{ \mathrm{out}}(\theta )}\sqrt{2\mu |V(r,\theta )-E_{k}|}\,{\rm d}r\right], $

(4) where

$ R_{\rm{in}}(\theta ) $ and$ R_{\rm{out}}(\theta ) $ represent the positions of the inner and outer barriers, respectively. The position$ R_{\rm{out}} $ of the outer barrier is derived from the equation$ V(R_{\rm{out}}(\theta ))=E_{k} $ .$ \mu =\frac{m_{\rm{p/2p}}m_{\rm{d}}}{m_{\rm{p/2p}}+m_{\rm{d}}}\approx 938.3\times A_{\rm{p/2p}}\times \frac{A_{\rm{d}}}{A} \text{ MeV/c}^{2} $ represents the reduced mass, where$ m_{\rm{p/2p}} $ and$ m_{\rm{d}} $ represent the masses of the emitted proton and daughter nuclei, respectively. Further,$ A_{\rm{p/2p}} $ ,$ A_{\rm{d}} $ , and$ A $ represent the mass numbers of the emitted proton, daughter nuclei, and proton emitter, respectively. In addition,$ E_{k}= Q_{\rm{p/2p}}(A- A_{\rm{p/2p}})/A $ represents the kinetic energy of the emitted proton. Incorporating electrostatic screening modifies$ Q_{\rm{p/2p}} $ , which is given by$ Q_{\rm{p/2p}}=\Delta M-(\Delta M_{\rm{d}}+\Delta M_{\rm{p/2p} })+k(Z^{\varepsilon }-Z_{\rm{d}}^{\varepsilon }), $

(5) where Z and

$ Z_{\rm{d}} $ represent the number of protons in the parent and daughter nuclei, respectively.$ \Delta M $ ,$ \Delta M_{\rm{d}} $ , and$ \Delta M_{\rm{p/2p}} $ represent the mass excesses of the parent nucleus, daughter nucleus, and emitted proton, respectively. The term$ k(Z^{\varepsilon }-Z_{\rm{d}}^{\varepsilon }) $ represents the charge screening effect where$ k=8.7$ eV,$ \varepsilon =2.517 $ for$ Z\geq 60 $ and$ k=13.6$ eV,$ \varepsilon =2.408 $ for$ Z<60 $ [63, 64].Summing the daughter nucleus radius and emitted proton radius yields the internal barrier position

$ R_{\rm{in}}(\theta ) $ .$ R_{\rm{in}}(\theta )=R_{\rm{p/2p}}+R_{\rm{d}}(\theta ), $

(6) $ R_{\rm{p/2p}}=r_{0}A_{\rm{p/2p}}^{1/3} $ represents the radius of the emitted proton, where$ A_{\rm{p/2p}} $ represents the mass number of the emitted proton.$ r_{0} $ represents the effective nuclear radius constant and is the only adjustable parameter in this model. Considering the effect of the deformation of the daughter nucleus, the radius is expressed as$ R_{\rm{d}}(\theta )=r_{0}A_{\rm{d}}^{1/3}\left[ 1+\sum\limits_{\lambda }\beta _{\lambda }Y_{\lambda 0}(\theta )\right], $

(7) where

$ \beta _{\lambda } $ represents the deformation parameter of the daughter nucleus ($ \lambda =2,4,6 $ correspond to the quadrupole, hexadecapole, and hexacontatetrapole deformations) and$ \beta _{\lambda } $ values are taken from FRDM2012 [65].$ Y_{\lambda 0}(\theta ) $ represents the spherical harmonics function.The total interaction potential

$ V(r,\theta ) $ between the daughter nucleus and the emitted proton can be expressed as$ V(r,\theta )= \begin{cases} -V_{0}, & 0\leq r\leq R_{\rm{in}}, \\ V_{\rm{c}}(r,\theta )+V_{l}(r), & r>R_{\rm{in}} \end{cases} $

(8) where

$ V_{0} $ represents the depth of the inner square well,$ V_{0}=25A_{\rm{p/2p}}$ MeV [66].$ V_{\rm{c}} $ represents the Coulomb interaction between the daughter nucleus and the emitted proton. Considering the effect of the deformation of the daughter nucleus on the Coulomb potential, the expression for the Coulomb potential is derived as$ \begin{aligned}[b] V_{\rm{c}}(r,\theta ) =\;&\frac{Z_{\rm{d}}Z_{\rm{p/2p}}{\rm{e}}^{2}}{r}+ \frac{3Z_{\rm{d}}Z_{\rm{p/2p}}{\rm{e}}^{2}}{r}\sum\limits_{\lambda =2,4,6}\frac{ 1}{2\lambda +1} \\ & \times \lbrack \frac{R_{\rm{d}}(\theta )}{r}]^{\lambda }Y_{\lambda 0}(\theta )\beta _{\lambda }, \end{aligned} $

(9) where r represents the distance between the daughter nucleus and the emitting proton. The centrifugal potential energy term is expressed as

$ V_{l}(r)=\frac{\hbar ^{2}l(l+1)}{2\mu r^{2}}, $

(10) where l represents the angular momentum carried by the emitted proton and determined by the spin parity conservation law. It can be expressed as [67]

$ l= \begin{cases} \Delta _{j} & {\rm{for\ even}}\; \Delta _{j}\; {\rm{and}}\; \pi =\pi _{\rm{d}}, \\ \Delta _{j}+1 & {\rm{for\ even}}\; \Delta _{j}\; {\rm{and}}\;\pi \neq \pi _{\rm{d}}, \\ \Delta _{j} & {\rm{for\ odd}}\; \Delta _{j}\; {\rm{and}}\; \pi \neq \pi _{\rm{d }}, \\ \Delta _{j}+1 & {\rm{for\ odd}}\; \Delta _{j}\; {\rm{and}}\; \pi =\pi _{\rm{d} }, \end{cases} $

(11) where

$ \pi $ and$ \pi _{\rm{d}} $ represent the parity of the parent and daughter nuclei, respectively.$ \Delta _{j}=|j-j_{\rm{d}}-j_{\rm{p}}^{\prime }| $ with$ j $ ,$ j_{\rm{d}} $ , and$ j_{\rm{p}}^{\prime } $ being the spins of the parent nucleus and emitted proton (for proton$ j^{\pi }=(1/2)^{+} $ ), respectively. We show the distribution of barriers in Fig. 1. In the first approximation, it is assumed to be given by the harmonic oscillator frequency in the Nilsson potential [68].

Figure 1. (color online) Relationship between the potential energy and center of mass distance of the decay system for 144Tm. The red and blue curves represent the Coulomb potential and centrifugal potential, respectively.

$ h\nu =\hbar \omega \simeq \frac{41}{A^{1/3}}{\rm{MeV}}, $

(12) where

$ h $ ,$ \hbar $ ,$ \omega $ , and$ A $ represent the Planck constant, reduced Planck constant, angular frequency, and mass number of proton emitters, respectively. -

In the DGLM model, the half-life and decay constant of the proton radioactivity are related as

$ T_{1/2}=\frac{\ln 2}{\lambda _{\rm{p/2p}}}, $

(1) where the decay constant

$ \lambda _{\rm{p/2p}} $ is defined as$ \lambda _{\rm{p/2p}}=S_{\rm{p/2p}}\nu P. $

(2) where

$ S_{\rm{p/2p}} $ represents the spectroscopic factor for either single-proton or two-proton radioactive systems,$ P $ represents the barrier penetration probability of the proton, and$ \nu $ represents its collision frequency with the potential barrier.When deformation effects are considered, the radius

$ R_{\rm{in}} $ and Coulomb potential$ V_{\rm{c}} $ of the square well change. Consequently, the total penetration probability is calculated by averaging over all directions as$ P=\frac{1}{2}\int_{0}^{\pi }P_{\theta }\sin \theta \,{\rm d}\theta, $

(3) where

$ \theta $ represents the angle between the subnucleus symmetry axis and radial vector. Under the classical Wentzel-Kramers-Brillouin approximation, this directional penetration probability takes the form$ P_{\theta }=\exp \left[ -\frac{2}{\hbar }\int_{R_{\rm{in}}(\theta )}^{R_{ \mathrm{out}}(\theta )}\sqrt{2\mu |V(r,\theta )-E_{k}|}\,{\rm d}r\right], $

(4) where

$ R_{\rm{in}}(\theta ) $ and$ R_{\rm{out}}(\theta ) $ represent the positions of the inner and outer barriers, respectively. The position$ R_{\rm{out}} $ of the outer barrier is derived from the equation$ V(R_{\rm{out}}(\theta ))=E_{k} $ .$ \mu =\frac{m_{\rm{p/2p}}m_{\rm{d}}}{m_{\rm{p/2p}}+m_{\rm{d}}}\approx 938.3\times A_{\rm{p/2p}}\times \frac{A_{\rm{d}}}{A} \text{ MeV/c}^{2} $ represents the reduced mass, where$ m_{\rm{p/2p}} $ and$ m_{\rm{d}} $ represent the masses of the emitted proton and daughter nuclei, respectively. Further,$ A_{\rm{p/2p}} $ ,$ A_{\rm{d}} $ , and$ A $ represent the mass numbers of the emitted proton, daughter nuclei, and proton emitter, respectively. In addition,$ E_{k}= Q_{\rm{p/2p}}(A-A_{\rm{p/2p}})/A $ represents the kinetic energy of the emitted proton. Incorporating electrostatic screening modifies$ Q_{\rm{p/2p}} $ , which is given by$ Q_{\rm{p/2p}}=\Delta M-(\Delta M_{\rm{d}}+\Delta M_{\rm{p/2p} })+k(Z^{\varepsilon }-Z_{\rm{d}}^{\varepsilon }), $

(5) where Z and

$ Z_{\rm{d}} $ represent the number of protons in the parent and daughter nuclei, respectively.$ \Delta M $ ,$ \Delta M_{\rm{d}} $ , and$ \Delta M_{\rm{p/2p}} $ represent the mass excesses of the parent nucleus, daughter nucleus, and emitted proton, respectively. The term$ k(Z^{\varepsilon }-Z_{\rm{d}}^{\varepsilon }) $ represents the charge screening effect where$ k=8.7$ eV,$ \varepsilon =2.517 $ for$ Z\geq 60 $ and$ k=13.6$ eV,$ \varepsilon =2.408 $ for$ Z<60 $ [63, 64].Summing the daughter nucleus radius and emitted proton radius yields the internal barrier position

$ R_{\rm{in}}(\theta ) $ .$ R_{\rm{in}}(\theta )=R_{\rm{p/2p}}+R_{\rm{d}}(\theta ), $

(6) $ R_{\rm{p/2p}}=r_{0}A_{\rm{p/2p}}^{1/3} $ represents the radius of the emitted proton, where$ A_{\rm{p/2p}} $ represents the mass number of the emitted proton.$ r_{0} $ represents the effective nuclear radius constant and is the only adjustable parameter in this model. Considering the effect of the deformation of the daughter nucleus, the radius is expressed as$ R_{\rm{d}}(\theta )=r_{0}A_{\rm{d}}^{1/3}\left[ 1+\sum\limits_{\lambda }\beta _{\lambda }Y_{\lambda 0}(\theta )\right], $

(7) where

$ \beta _{\lambda } $ represents the deformation parameter of the daughter nucleus ($ \lambda =2,4,6 $ correspond to the quadrupole, hexadecapole, and hexacontatetrapole deformations) and$ \beta _{\lambda } $ values are taken from FRDM2012 [65].$ Y_{\lambda 0}(\theta ) $ represents the spherical harmonics function.The total interaction potential

$ V(r,\theta ) $ between the daughter nucleus and the emitted proton can be expressed as$ V(r,\theta )= \begin{cases} -V_{0}, & 0\leq r\leq R_{\rm{in}}, \\ V_{\rm{c}}(r,\theta )+V_{l}(r), & r>R_{\rm{in}} \end{cases} $

(8) where

$ V_{0} $ represents the depth of the inner square well,$ V_{0}=25A_{\rm{p/2p}}$ MeV [66].$ V_{\rm{c}} $ represents the Coulomb interaction between the daughter nucleus and the emitted proton. Considering the effect of the deformation of the daughter nucleus on the Coulomb potential, the expression for the Coulomb potential is derived as$ \begin{aligned}[b] V_{\rm{c}}(r,\theta ) =\;&\frac{Z_{\rm{d}}Z_{\rm{p/2p}}{\rm{e}}^{2}}{r}+ \frac{3Z_{\rm{d}}Z_{\rm{p/2p}}{\rm{e}}^{2}}{r}\sum\limits_{\lambda =2,4,6}\frac{ 1}{2\lambda +1} \\ & \times \lbrack \frac{R_{\rm{d}}(\theta )}{r}]^{\lambda }Y_{\lambda 0}(\theta )\beta _{\lambda }, \end{aligned} $

(9) where r represents the distance between the daughter nucleus and the emitting proton. The centrifugal potential energy term is expressed as

$ V_{l}(r)=\frac{\hbar ^{2}l(l+1)}{2\mu r^{2}}, $

(10) where l represents the angular momentum carried by the emitted proton and determined by the spin parity conservation law. It can be expressed as [67]

$ l= \begin{cases} \Delta _{j} & {\rm{for\ even}}\; \Delta _{j}\; {\rm{and}}\; \pi =\pi _{\rm{d}}, \\ \Delta _{j}+1 & {\rm{for\ even}}\; \Delta _{j}\; {\rm{and}}\;\pi \neq \pi _{\rm{d}}, \\ \Delta _{j} & {\rm{for\ odd}}\; \Delta _{j}\; {\rm{and}}\; \pi \neq \pi _{\rm{d }}, \\ \Delta _{j}+1 & {\rm{for\ odd}}\; \Delta _{j}\; {\rm{and}}\; \pi =\pi _{\rm{d} }, \end{cases} $

(11) where

$ \pi $ and$ \pi _{\rm{d}} $ represent the parity of the parent and daughter nuclei, respectively.$ \Delta _{j}=|j-j_{\rm{d}}-j_{\rm{p}}^{\prime }| $ with$ j $ ,$ j_{\rm{d}} $ , and$ j_{\rm{p}}^{\prime } $ being the spins of the parent nucleus and emitted proton (for proton$ j^{\pi }=(1/2)^{+} $ ), respectively. We show the distribution of barriers in Fig. 1. In the first approximation, it is assumed to be given by the harmonic oscillator frequency in the Nilsson potential [68].

Figure 1. (color online) Relationship between the potential energy and center of mass distance of the decay system for 144Tm. The red and blue curves represent the Coulomb potential and centrifugal potential, respectively.

$ h\nu =\hbar \omega \simeq \frac{41}{A^{1/3}}{\rm{MeV}}, $

(12) where

$ h $ ,$ \hbar $ ,$ \omega $ , and$ A $ represent the Planck constant, reduced Planck constant, angular frequency, and mass number of proton emitters, respectively. -

In the DGLM model, the half-life and decay constant of the proton radioactivity are related as

$ T_{1/2}=\frac{\ln 2}{\lambda _{\rm{p/2p}}}, $

(1) where the decay constant

$ \lambda _{\rm{p/2p}} $ is defined as$ \lambda _{\rm{p/2p}}=S_{\rm{p/2p}}\nu P. $

(2) where

$ S_{\rm{p/2p}} $ represents the spectroscopic factor for either single-proton or two-proton radioactive systems,$ P $ represents the barrier penetration probability of the proton, and$ \nu $ represents its collision frequency with the potential barrier.When deformation effects are considered, the radius

$ R_{\rm{in}} $ and Coulomb potential$ V_{\rm{c}} $ of the square well change. Consequently, the total penetration probability is calculated by averaging over all directions as$ P=\frac{1}{2}\int_{0}^{\pi }P_{\theta }\sin \theta \,{\rm d}\theta, $

(3) where

$ \theta $ represents the angle between the subnucleus symmetry axis and radial vector. Under the classical Wentzel-Kramers-Brillouin approximation, this directional penetration probability takes the form$ P_{\theta }=\exp \left[ -\frac{2}{\hbar }\int_{R_{\rm{in}}(\theta )}^{R_{ \mathrm{out}}(\theta )}\sqrt{2\mu |V(r,\theta )-E_{k}|}\,{\rm d}r\right], $

(4) where

$ R_{\rm{in}}(\theta ) $ and$ R_{\rm{out}}(\theta ) $ represent the positions of the inner and outer barriers, respectively. The position$ R_{\rm{out}} $ of the outer barrier is derived from the equation$ V(R_{\rm{out}}(\theta ))=E_{k} $ .$ \mu =\frac{m_{\rm{p/2p}}m_{\rm{d}}}{m_{\rm{p/2p}}+m_{\rm{d}}}\approx 938.3\times A_{\rm{p/2p}}\times \frac{A_{\rm{d}}}{A} \text{ MeV/c}^{2} $ represents the reduced mass, where$ m_{\rm{p/2p}} $ and$ m_{\rm{d}} $ represent the masses of the emitted proton and daughter nuclei, respectively. Further,$ A_{\rm{p/2p}} $ ,$ A_{\rm{d}} $ , and$ A $ represent the mass numbers of the emitted proton, daughter nuclei, and proton emitter, respectively. In addition,$ E_{k}= Q_{\rm{p/2p}}(A-A_{\rm{p/2p}})/A $ represents the kinetic energy of the emitted proton. Incorporating electrostatic screening modifies$ Q_{\rm{p/2p}} $ , which is given by$ Q_{\rm{p/2p}}=\Delta M-(\Delta M_{\rm{d}}+\Delta M_{\rm{p/2p} })+k(Z^{\varepsilon }-Z_{\rm{d}}^{\varepsilon }), $

(5) where Z and

$ Z_{\rm{d}} $ represent the number of protons in the parent and daughter nuclei, respectively.$ \Delta M $ ,$ \Delta M_{\rm{d}} $ , and$ \Delta M_{\rm{p/2p}} $ represent the mass excesses of the parent nucleus, daughter nucleus, and emitted proton, respectively. The term$ k(Z^{\varepsilon }-Z_{\rm{d}}^{\varepsilon }) $ represents the charge screening effect where$ k=8.7$ eV,$ \varepsilon =2.517 $ for$ Z\geq 60 $ and$ k=13.6$ eV,$ \varepsilon =2.408 $ for$ Z<60 $ [63, 64].Summing the daughter nucleus radius and emitted proton radius yields the internal barrier position

$ R_{\rm{in}}(\theta ) $ .$ R_{\rm{in}}(\theta )=R_{\rm{p/2p}}+R_{\rm{d}}(\theta ), $

(6) $ R_{\rm{p/2p}}=r_{0}A_{\rm{p/2p}}^{1/3} $ represents the radius of the emitted proton, where$ A_{\rm{p/2p}} $ represents the mass number of the emitted proton.$ r_{0} $ represents the effective nuclear radius constant and is the only adjustable parameter in this model. Considering the effect of the deformation of the daughter nucleus, the radius is expressed as$ R_{\rm{d}}(\theta )=r_{0}A_{\rm{d}}^{1/3}\left[ 1+\sum\limits_{\lambda }\beta _{\lambda }Y_{\lambda 0}(\theta )\right], $

(7) where

$ \beta _{\lambda } $ represents the deformation parameter of the daughter nucleus ($ \lambda =2,4,6 $ correspond to the quadrupole, hexadecapole, and hexacontatetrapole deformations) and$ \beta _{\lambda } $ values are taken from FRDM2012 [65].$ Y_{\lambda 0}(\theta ) $ represents the spherical harmonics function.The total interaction potential

$ V(r,\theta ) $ between the daughter nucleus and the emitted proton can be expressed as$ V(r,\theta )= \begin{cases} -V_{0}, & 0\leq r\leq R_{\rm{in}}, \\ V_{\rm{c}}(r,\theta )+V_{l}(r), & r>R_{\rm{in}} \end{cases} $

(8) where

$ V_{0} $ represents the depth of the inner square well,$ V_{0}=25A_{\rm{p/2p}}$ MeV [66].$ V_{\rm{c}} $ represents the Coulomb interaction between the daughter nucleus and the emitted proton. Considering the effect of the deformation of the daughter nucleus on the Coulomb potential, the expression for the Coulomb potential is derived as$ \begin{aligned}[b] V_{\rm{c}}(r,\theta ) =\;&\frac{Z_{\rm{d}}Z_{\rm{p/2p}}{\rm{e}}^{2}}{r}+ \frac{3Z_{\rm{d}}Z_{\rm{p/2p}}{\rm{e}}^{2}}{r}\sum\limits_{\lambda =2,4,6}\frac{ 1}{2\lambda +1} \\ & \times \lbrack \frac{R_{\rm{d}}(\theta )}{r}]^{\lambda }Y_{\lambda 0}(\theta )\beta _{\lambda }, \end{aligned} $

(9) where r represents the distance between the daughter nucleus and the emitting proton. The centrifugal potential energy term is expressed as

$ V_{l}(r)=\frac{\hbar ^{2}l(l+1)}{2\mu r^{2}}, $

(10) where l represents the angular momentum carried by the emitted proton and determined by the spin parity conservation law. It can be expressed as [67]

$ l= \begin{cases} \Delta _{j} & {\rm{for\ even}}\; \Delta _{j}\; {\rm{and}}\; \pi =\pi _{\rm{d}}, \\ \Delta _{j}+1 & {\rm{for\ even}}\; \Delta _{j}\; {\rm{and}}\;\pi \neq \pi _{\rm{d}}, \\ \Delta _{j} & {\rm{for\ odd}}\; \Delta _{j}\; {\rm{and}}\; \pi \neq \pi _{\rm{d }}, \\ \Delta _{j}+1 & {\rm{for\ odd}}\; \Delta _{j}\; {\rm{and}}\; \pi =\pi _{\rm{d} }, \end{cases} $

(11) where

$ \pi $ and$ \pi _{\rm{d}} $ represent the parity of the parent and daughter nuclei, respectively.$ \Delta _{j}=|j-j_{\rm{d}}-j_{\rm{p}}^{\prime }| $ with$ j $ ,$ j_{\rm{d}} $ , and$ j_{\rm{p}}^{\prime } $ being the spins of the parent nucleus and emitted proton (for proton$ j^{\pi }=(1/2)^{+} $ ), respectively. We show the distribution of barriers in Fig. 1. In the first approximation, it is assumed to be given by the harmonic oscillator frequency in the Nilsson potential [68].

Figure 1. (color online) Relationship between the potential energy and center of mass distance of the decay system for 144Tm. The red and blue curves represent the Coulomb potential and centrifugal potential, respectively.

$ h\nu =\hbar \omega \simeq \frac{41}{A^{1/3}}{\rm{MeV}}, $

(12) where

$ h $ ,$ \hbar $ ,$ \omega $ , and$ A $ represent the Planck constant, reduced Planck constant, angular frequency, and mass number of proton emitters, respectively. -

In this study, we calculate the half-lives of two-proton radioactivity for nuclei with atomic numbers Z=4~36 based on the DGLM. In the two-proton (2p) radioactivity, the spectroscopic factor

$ S_{\rm 2p}=G^{2}[A/(A-2)]^{2n}\chi^{2} $ [51]. Here,$ G^{2}=(2n)!/[2^{2n}(n!)^{2}] $ [69], and n represents the average principal proton oscillator quantum number given by$ n\approx(3{Z})^{1/3}-1 $ [70]. In this study,$ \chi^{2} $ =0.0143 according to a previous study by Cui et al. [71]. For a comparative analysis, our calculated radioactivity half-lives were compared with the experimental data as well as predictions from the GLDM [71] and other empirical formulas. All results are compiled in Table 1. In Table 1, the first three columns list the 2p radioactive emitters, 2p radioactivity released energy, and experimental 2p radioactivity half-lives, respectively. The last three columns present the theoretical 2p radioactivity half-lives calculated using the DGLM, GLDM, and empirical formula of Sreeja.Nucleus $ {}^{A}Z $

Q2p /MeV $ \log_{10}T_{1/2}(s) $

Exp DGLM GLDM [71] Sreeja [57] 6Be 1.371 [15] −20.30 [15] −19.83 −19.37 −21.95 12O 1.638 [20] >−20.20 [20] −18.1 −19.71 −18.47 1.820 [7] −20.94 [7] −18.38 −19.46 −18.79 1.790 [18] −20.10 [18] −18.31 −19.43 −18.74 1.800 [19] −20.12 [19] −18.32 −19.44 −18.76 16Ne 1.330 [7] −20.64 [7] −16.28 −16.45 −15.94 1.400 [17] −20.38 [17] −16.48 −16.63 −16.16 19Mg 0.750 [13] −11.40 [13] −11.50 −11.79 −10.66 45Fe 1.100 [10] −2.40 [10] −2.11 −2.23 −1.25 1.140 [9] −2.07 [9] −2.60 −2.71 −1.66 1.154 [12] −2.55 [12] −2.75 −2.87 −1.80 1.210 [72] −2.42 [72] −3.38 −3.50 −2.34 48Ni 1.290 [73] −2.52 [73] −2.58 −2.62 −1.61 1.350 [12] −2.08 [12] −3.20 −3.24 −2.13 1.310 [74] −2.52 [74] −2.79 −2.83 −1.80 54Zn 1.280 [75] −2.79 [75] −0.95 −0.87 −0.10 1.480 [11] −2.43 [11] −3.01 −2.95 −1.83 67Kr 1.690 [14] −1.70 [14] −0.81 −1.25 0.31 Table 1. 2p proton radioactivity half-lives. The experimental 2p radioactivity half-lives and decay energies were obtained from the literatures.

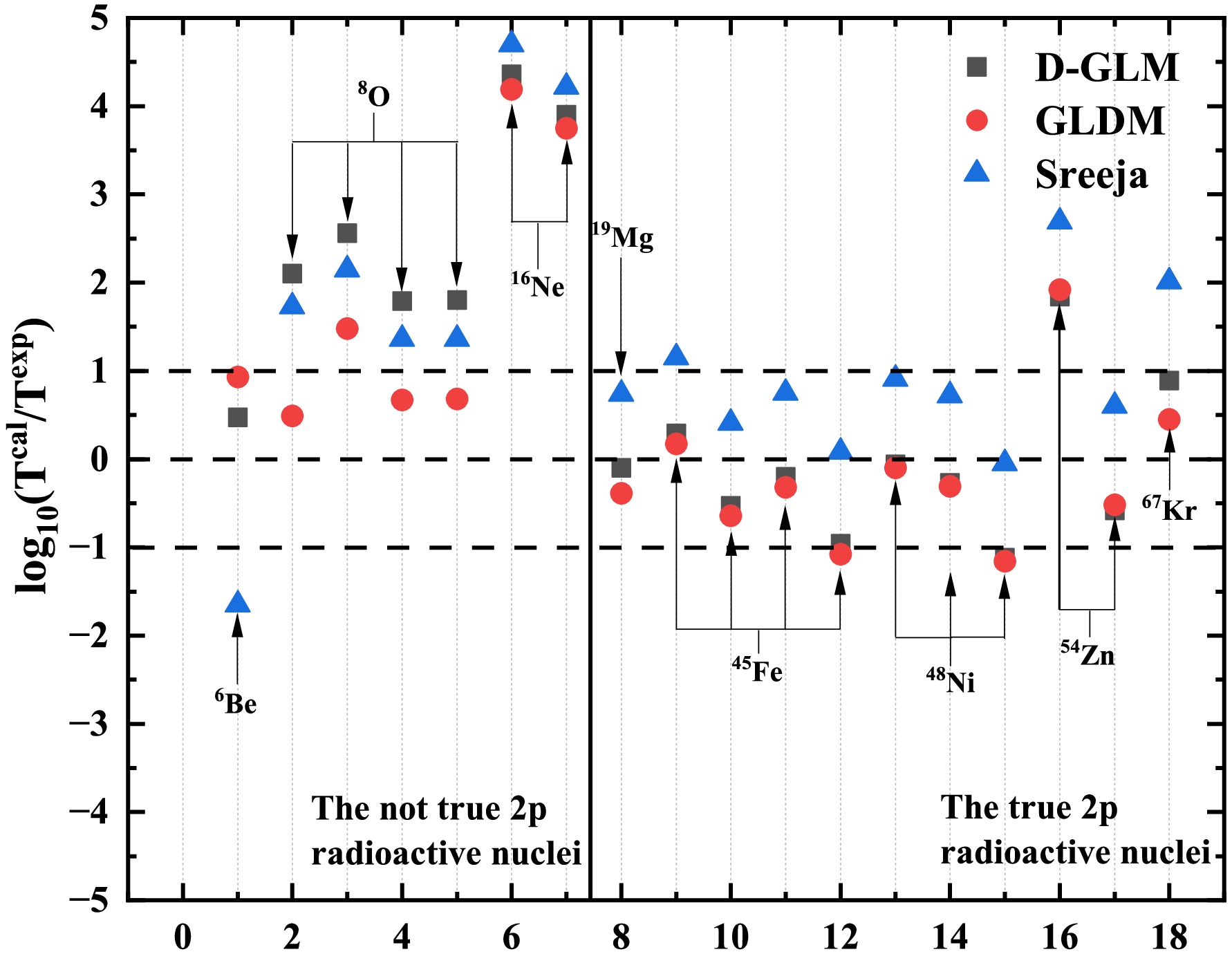

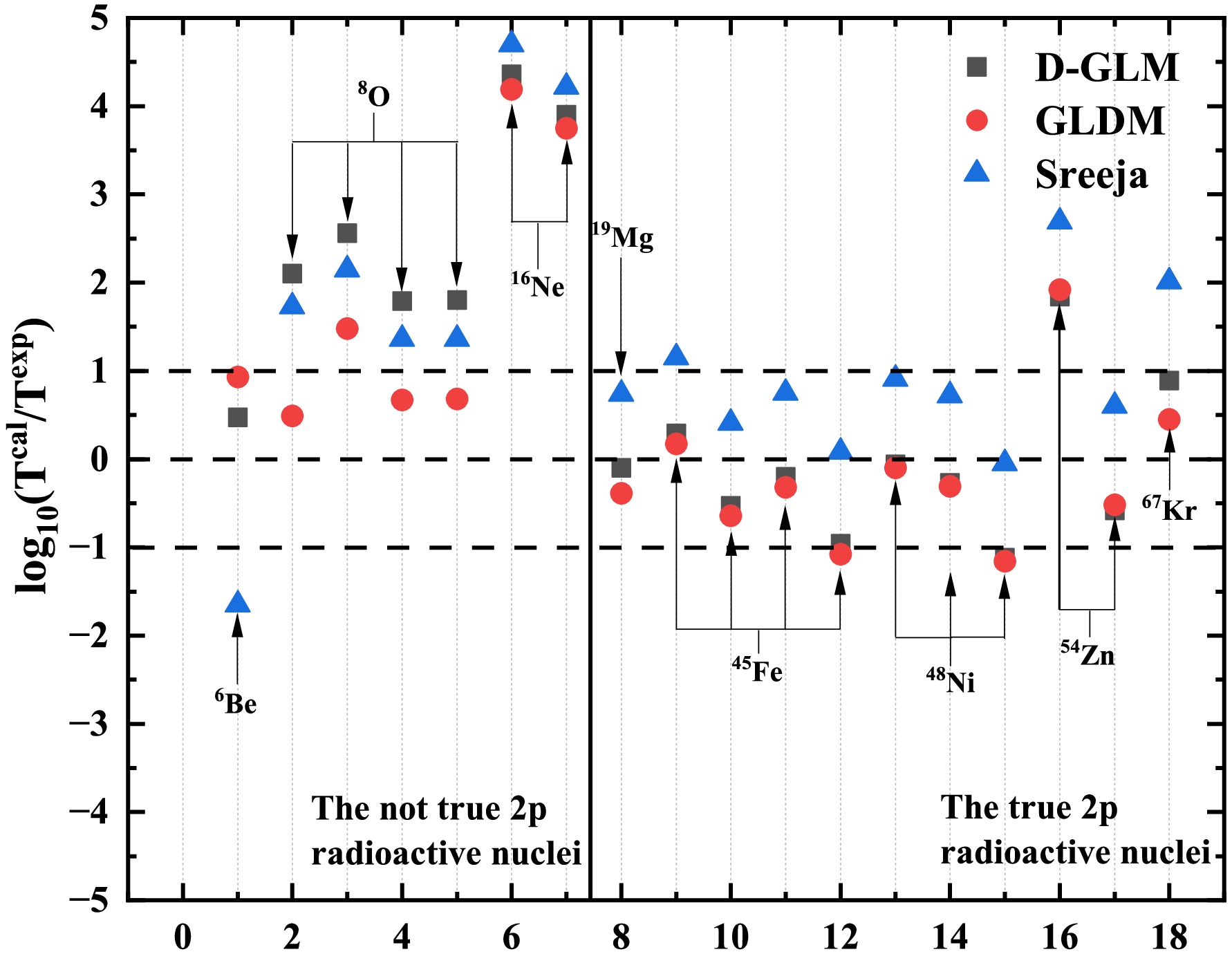

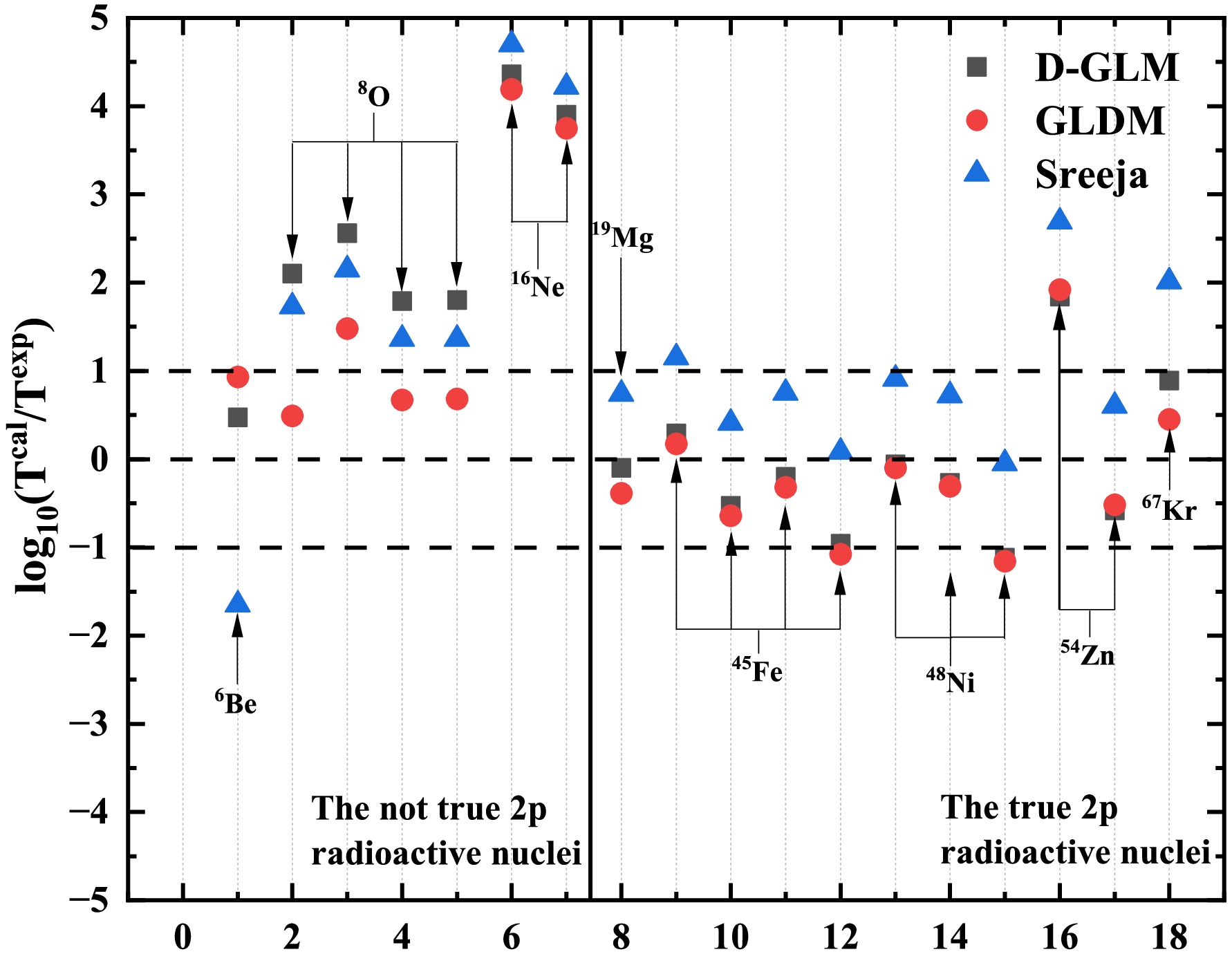

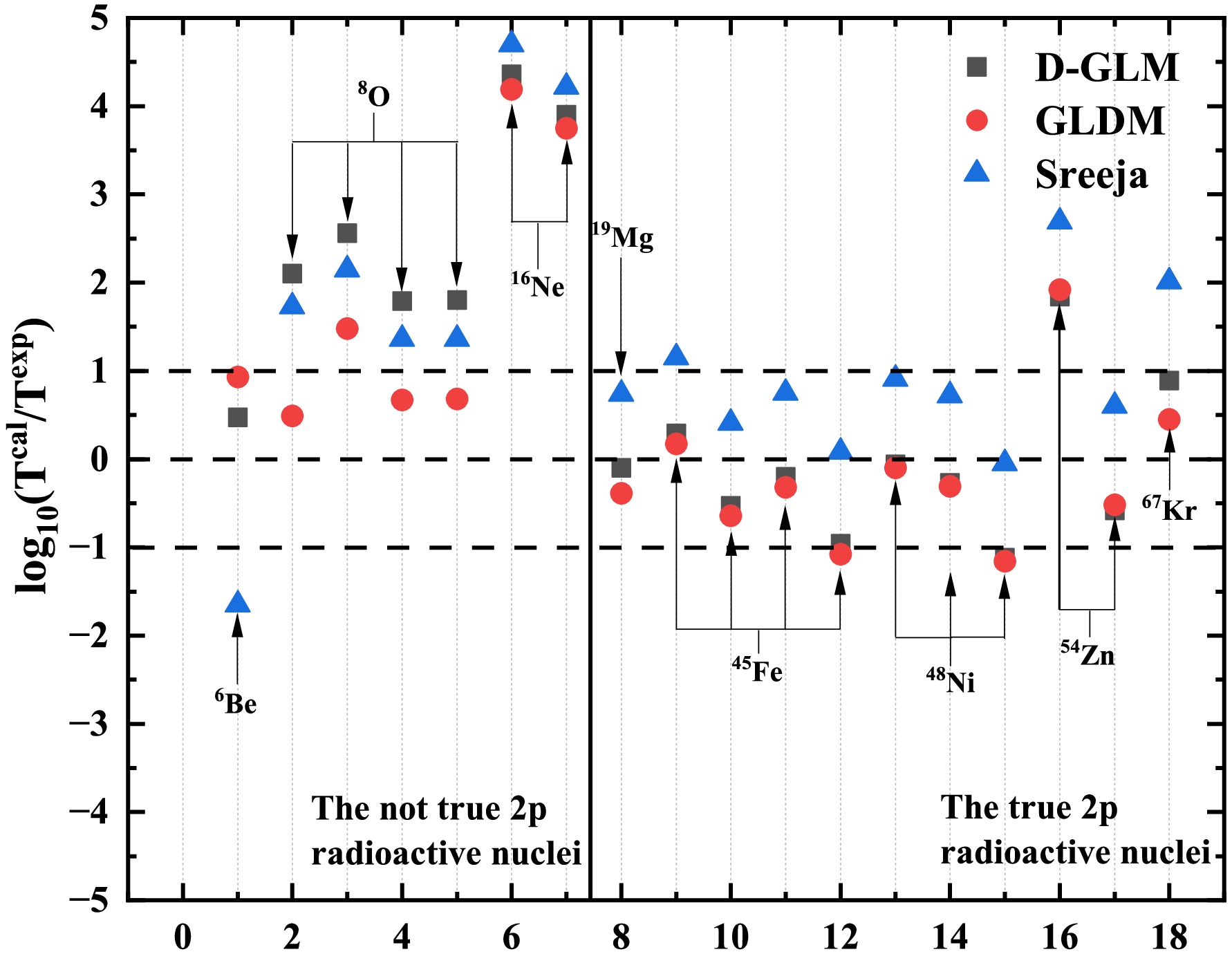

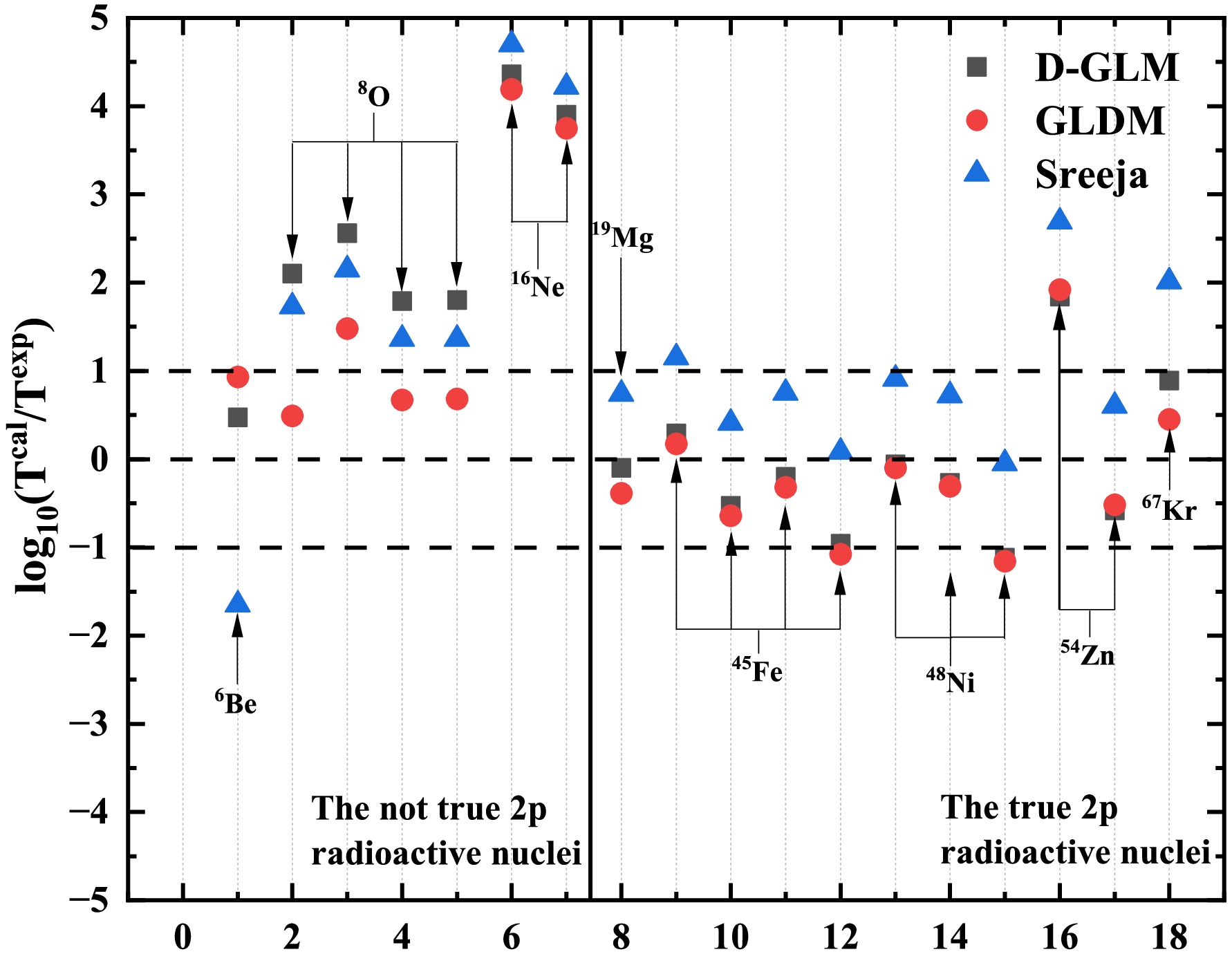

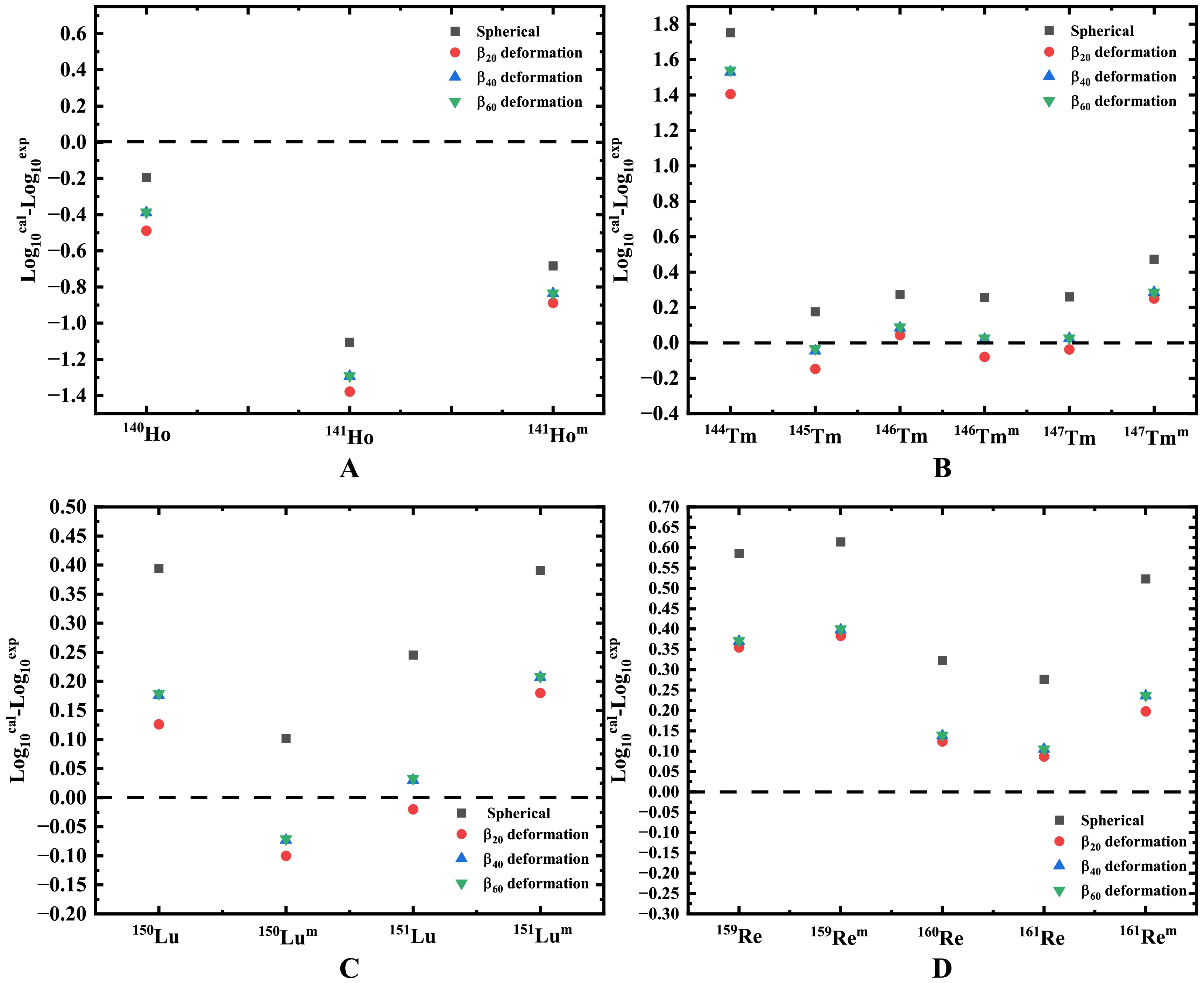

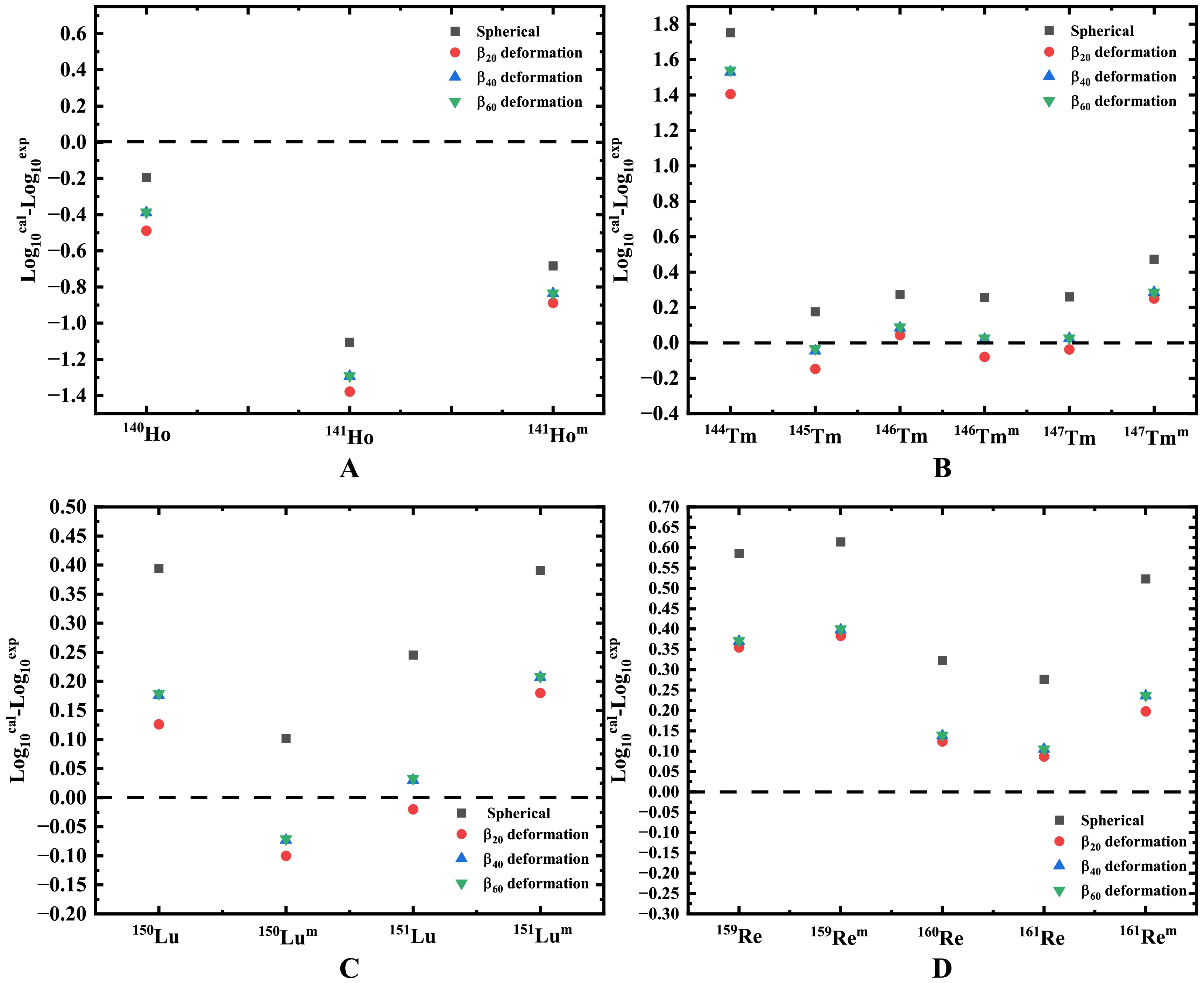

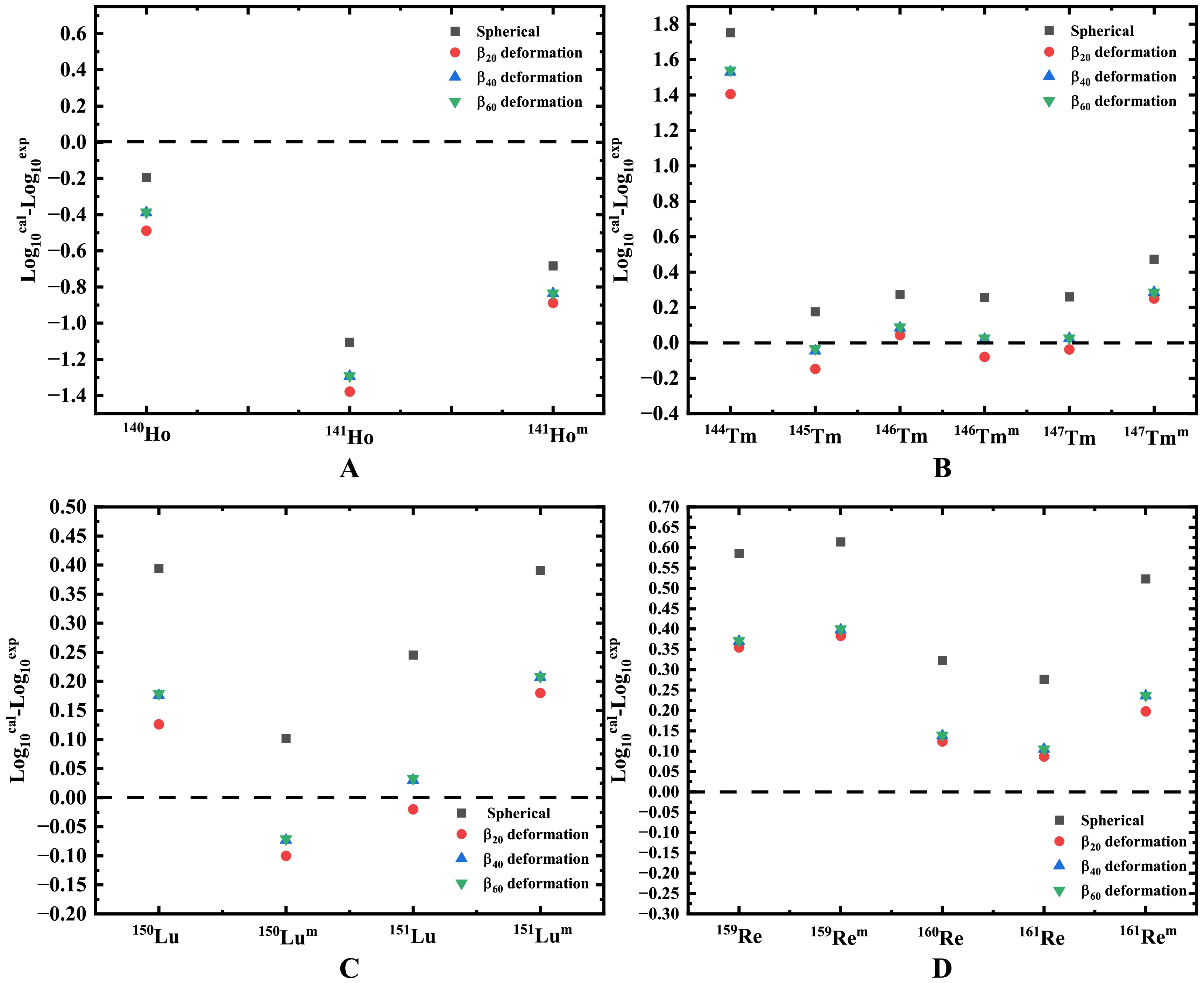

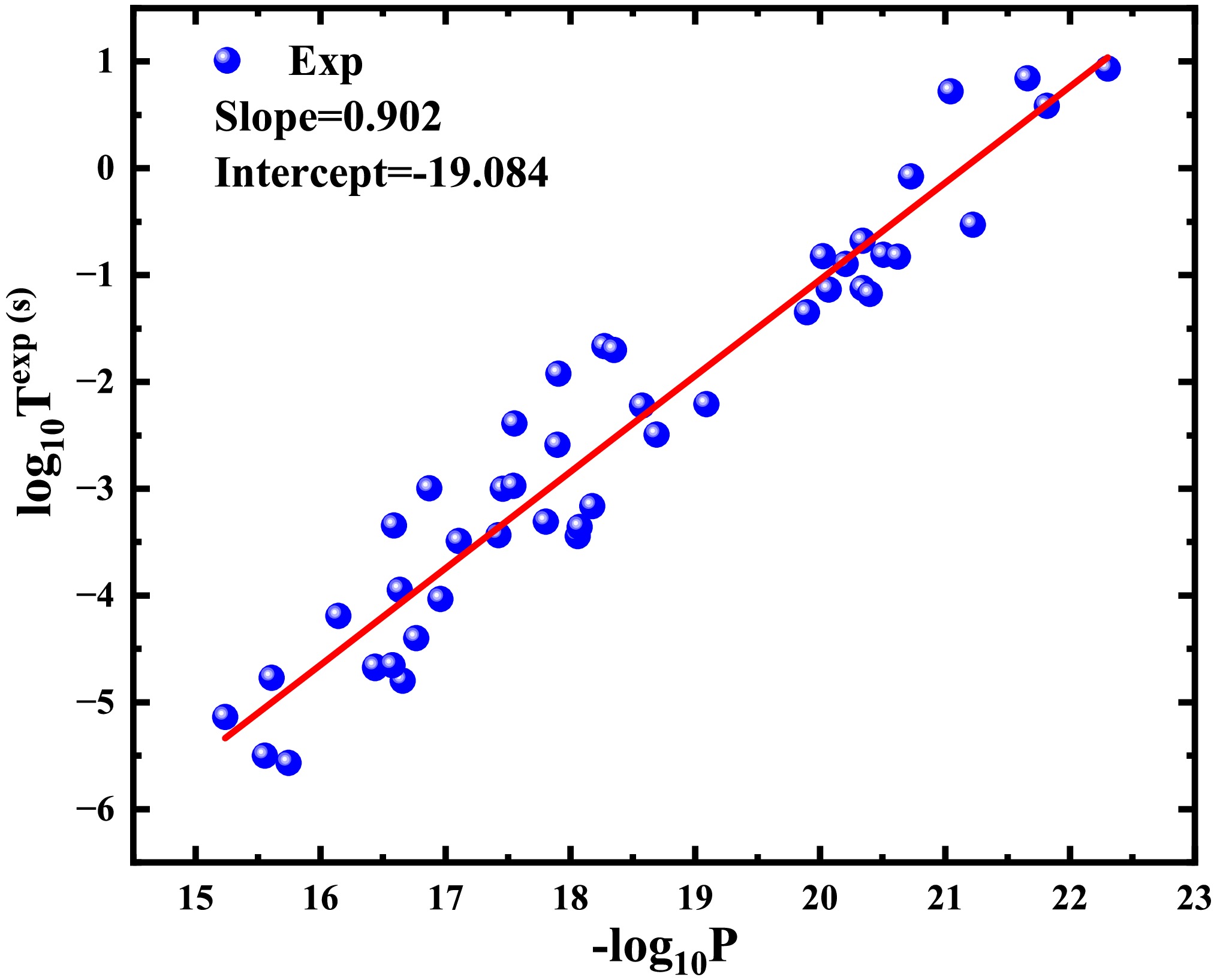

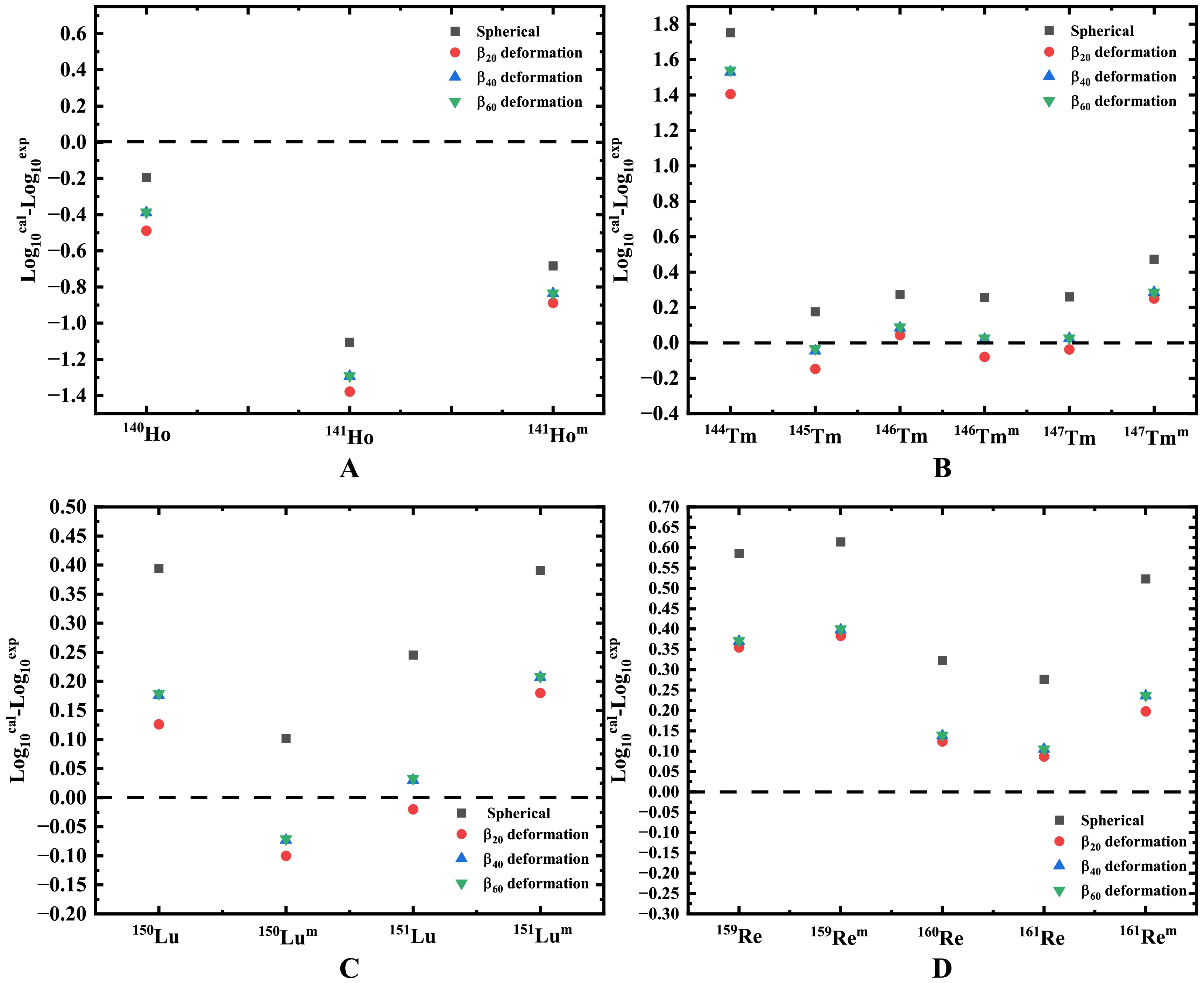

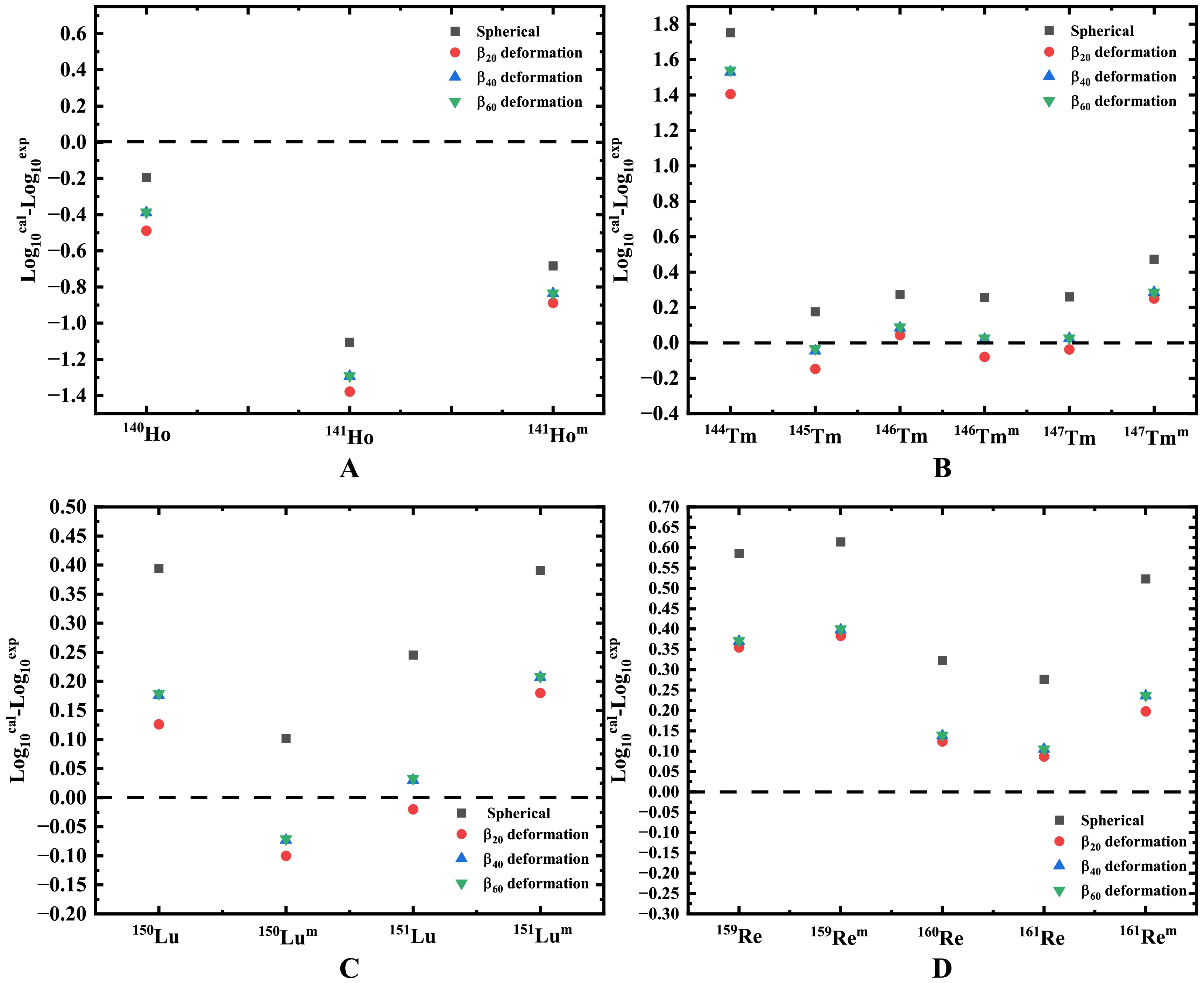

For a more intuitive comparison, logarithmic differences between the calculated and experimental radioactivity half-lives are presented in Fig. 2. As shown in the figure, the deviations between the calculated and experimental half-lives for true 2p radioactive nuclei fall within one order of magnitude. This indicates that the DGLM successfully reproduces the experimental 2p radioactive half-lives. The standard deviation (

$ \sigma $ ), as defined below, visually illustrates the discrepancy between the modeled half-lives and experimental results

Figure 2. (color online) Discrepancies between calculated and experimental 2p radioactivity half-lives. It encompasses both true 2p radioactivity nuclei and nuclei that do not exhibit true 2p radioactivity.

$ \begin{eqnarray} \sigma = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\sum\limits_{i=1}^N \left(\log_{10}T_{\rm{cal}}^i - \log_{10}T_{\rm{exp}}^i\right)^2} \ .\end{eqnarray} $

(13) where

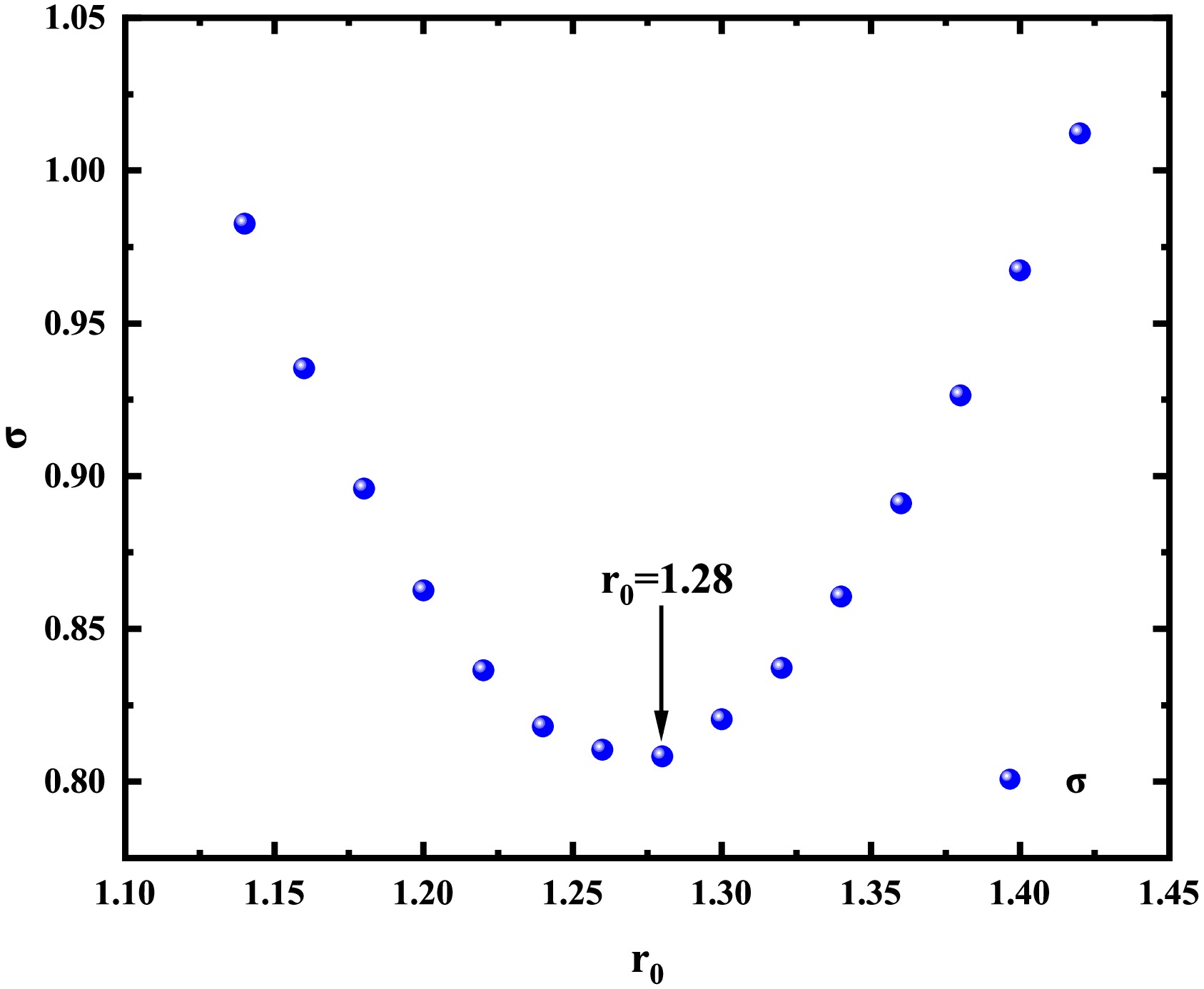

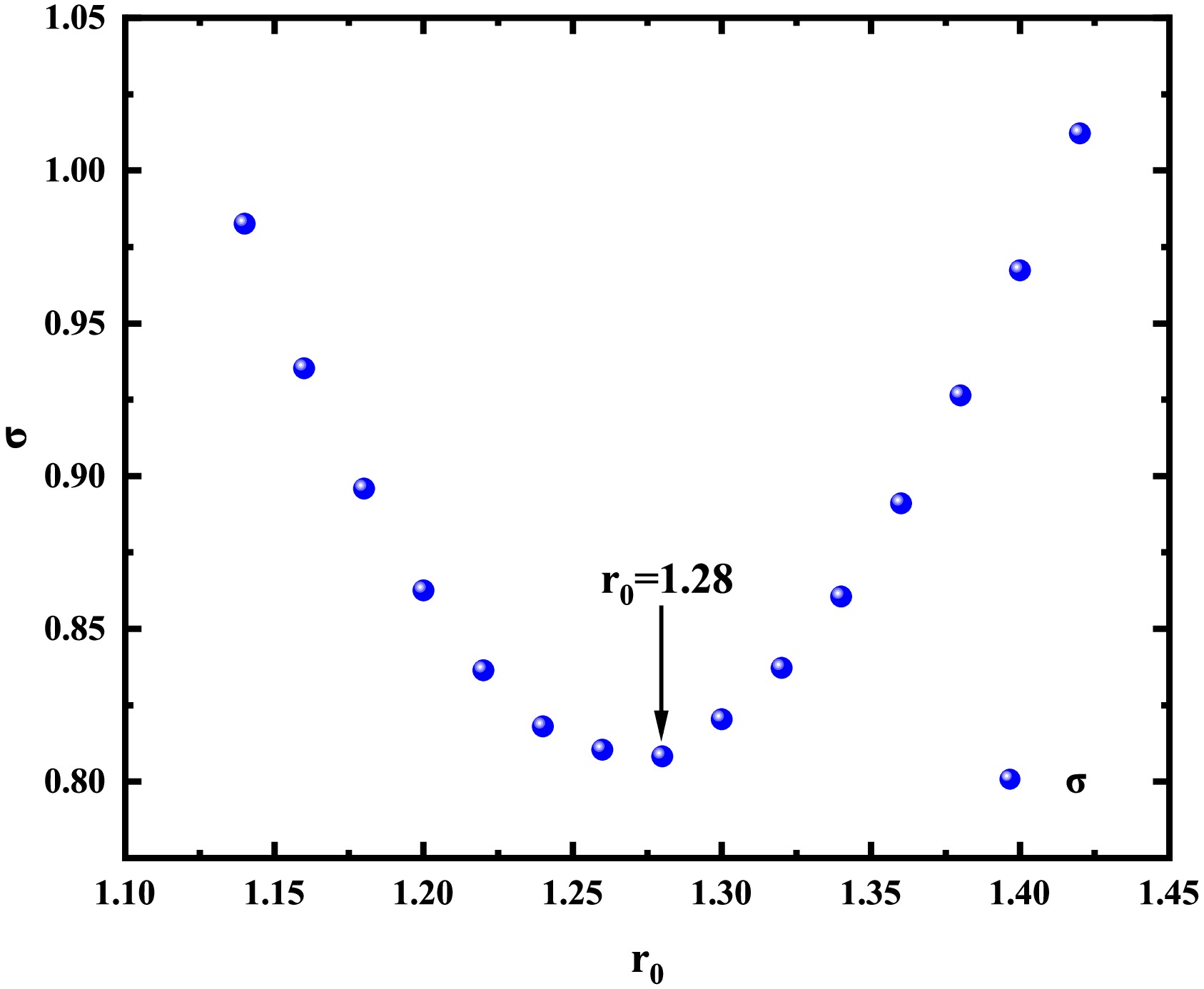

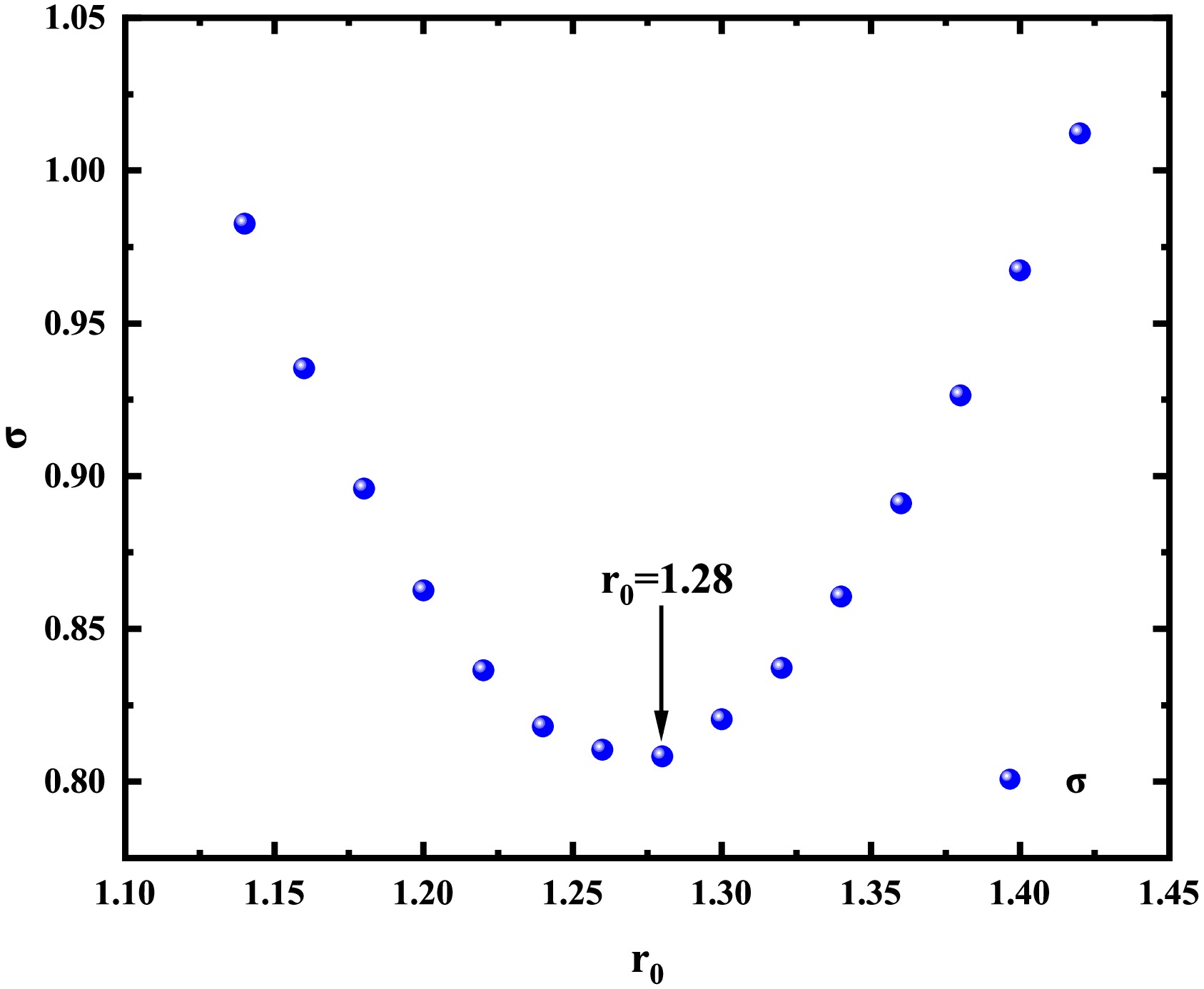

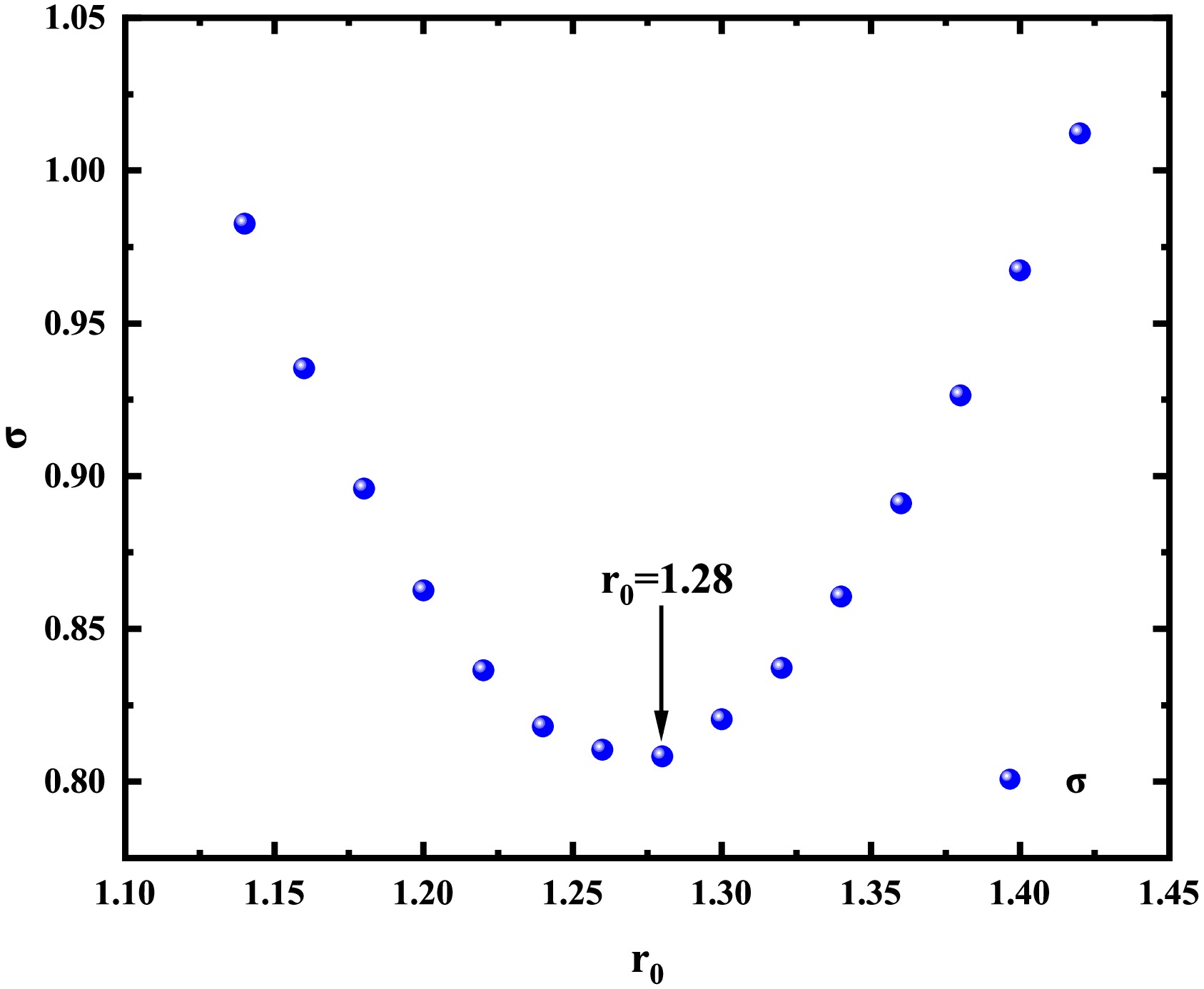

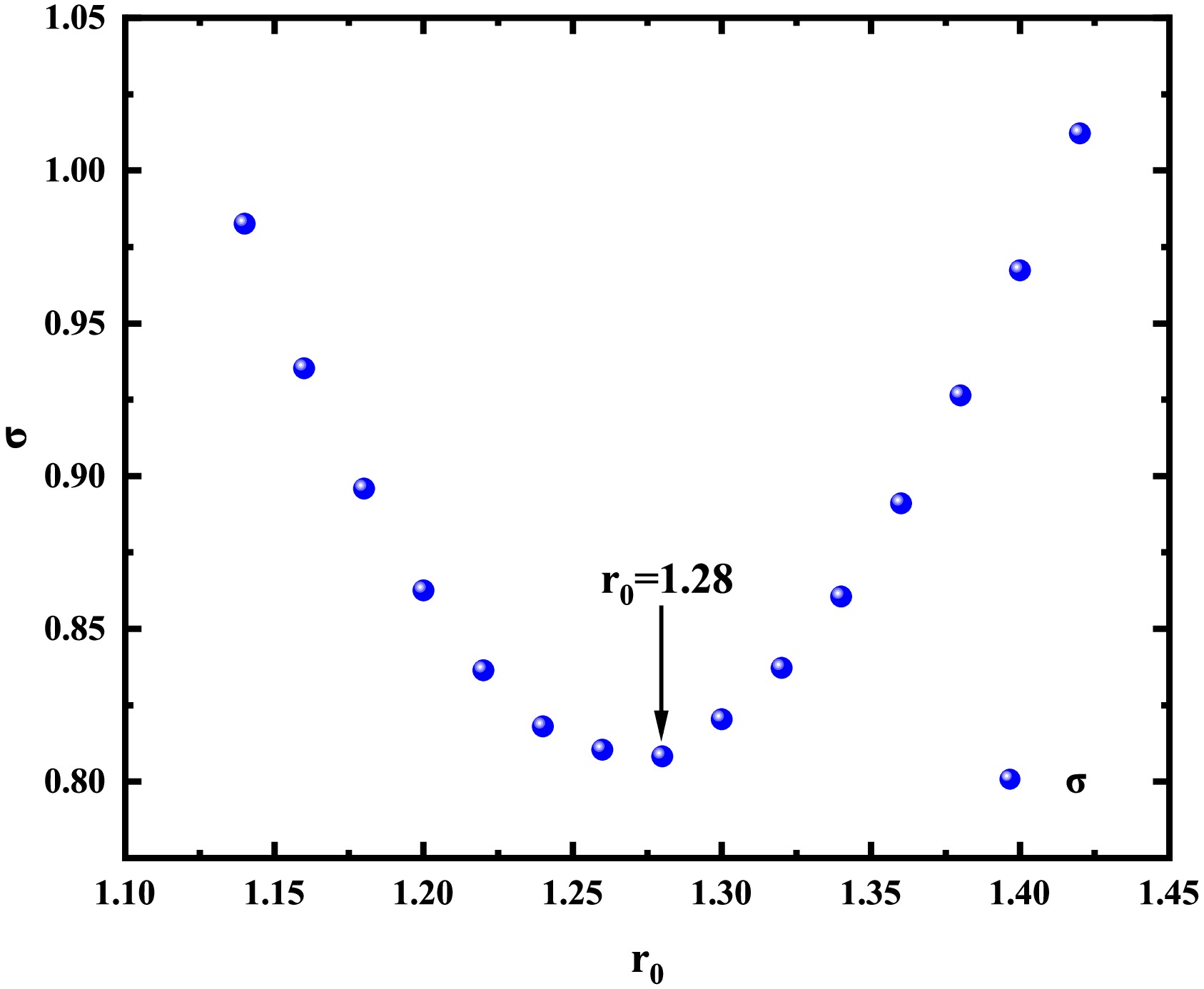

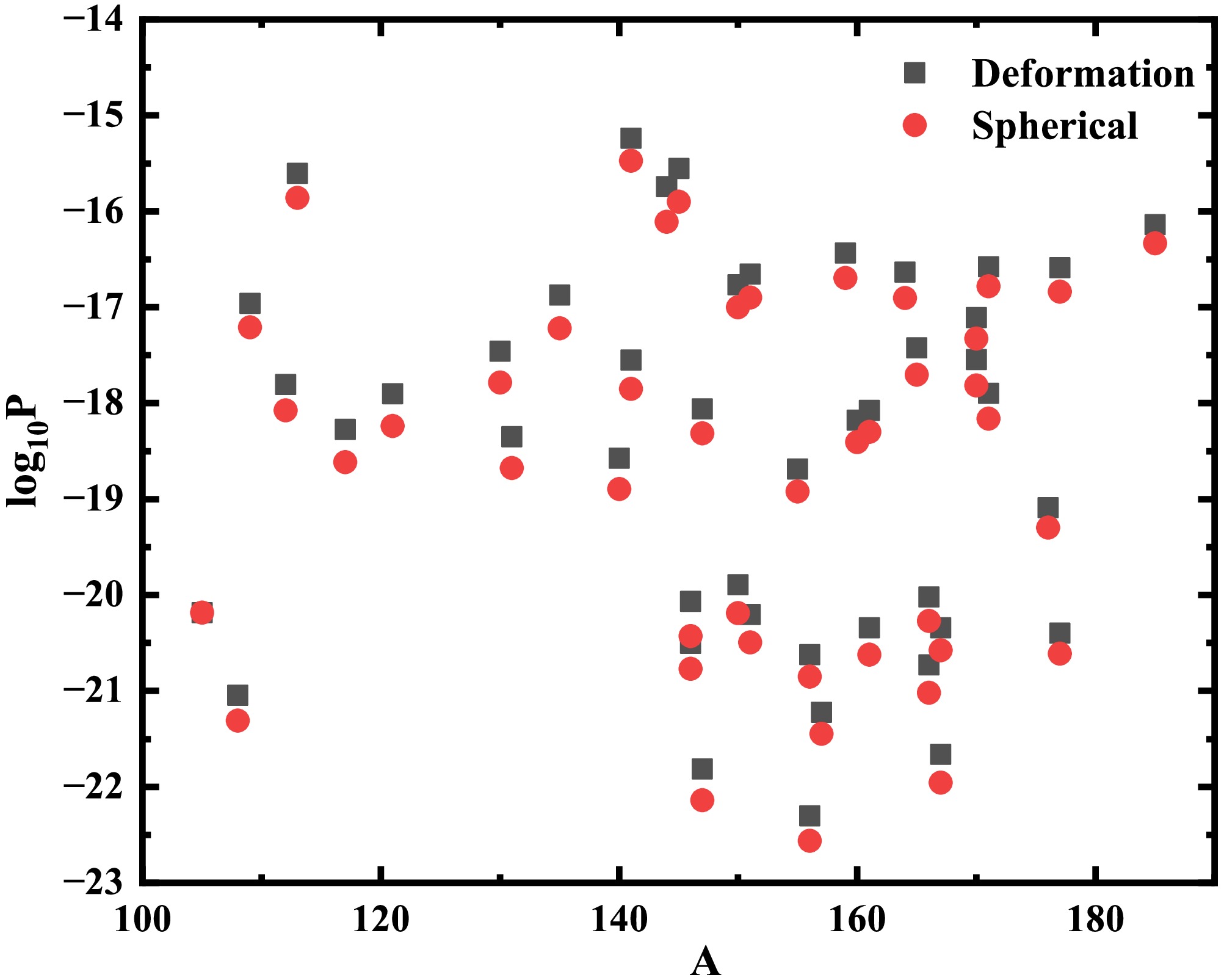

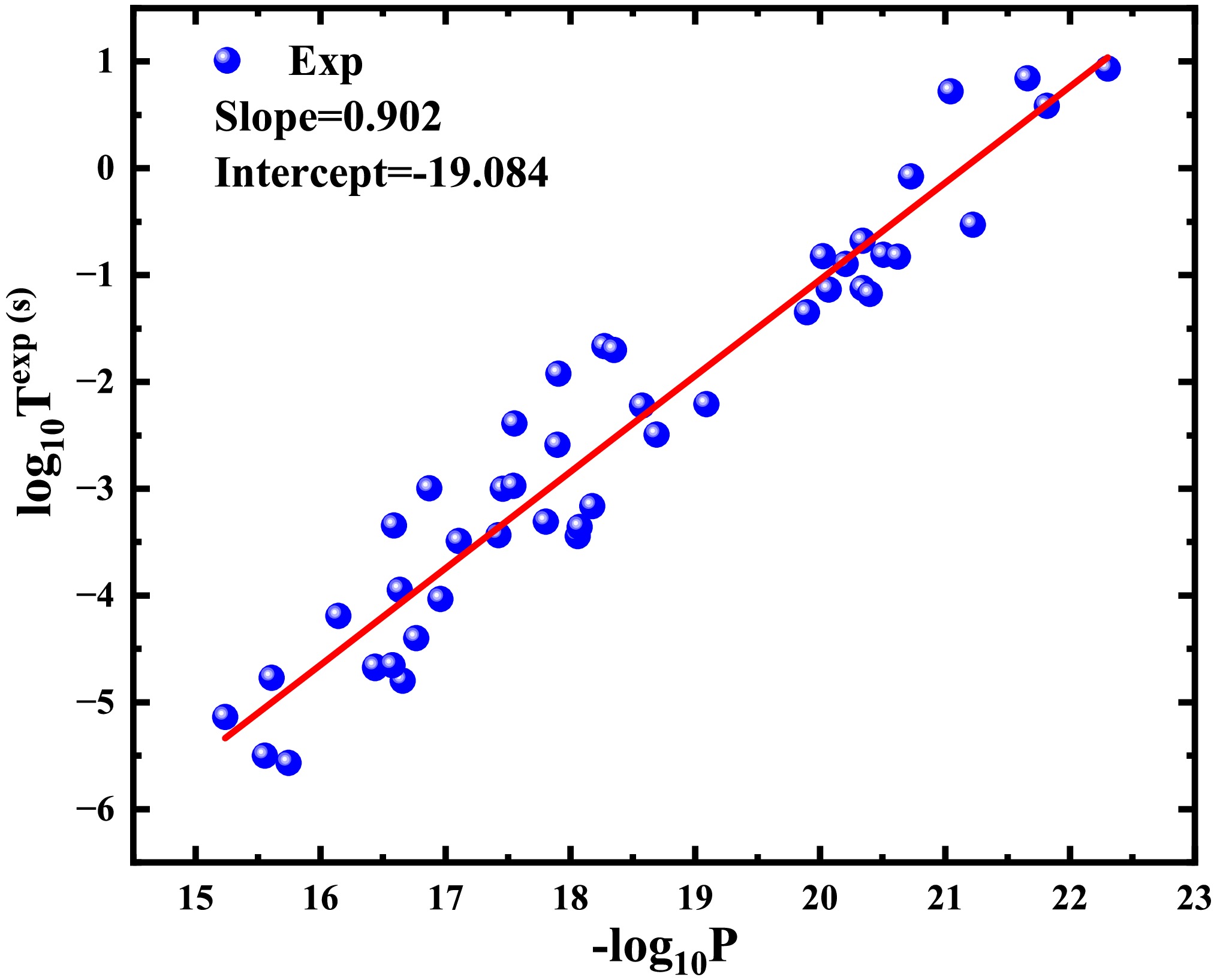

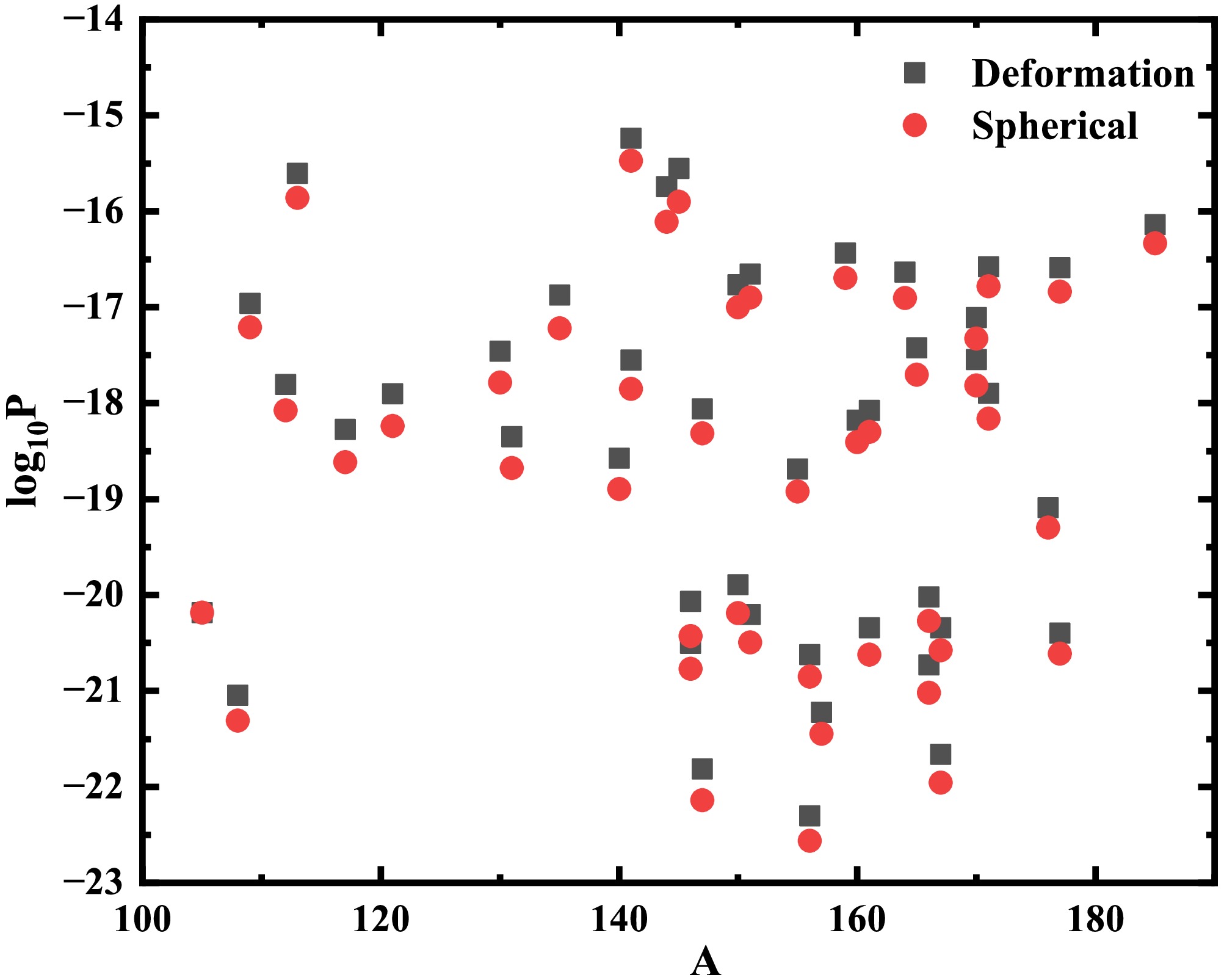

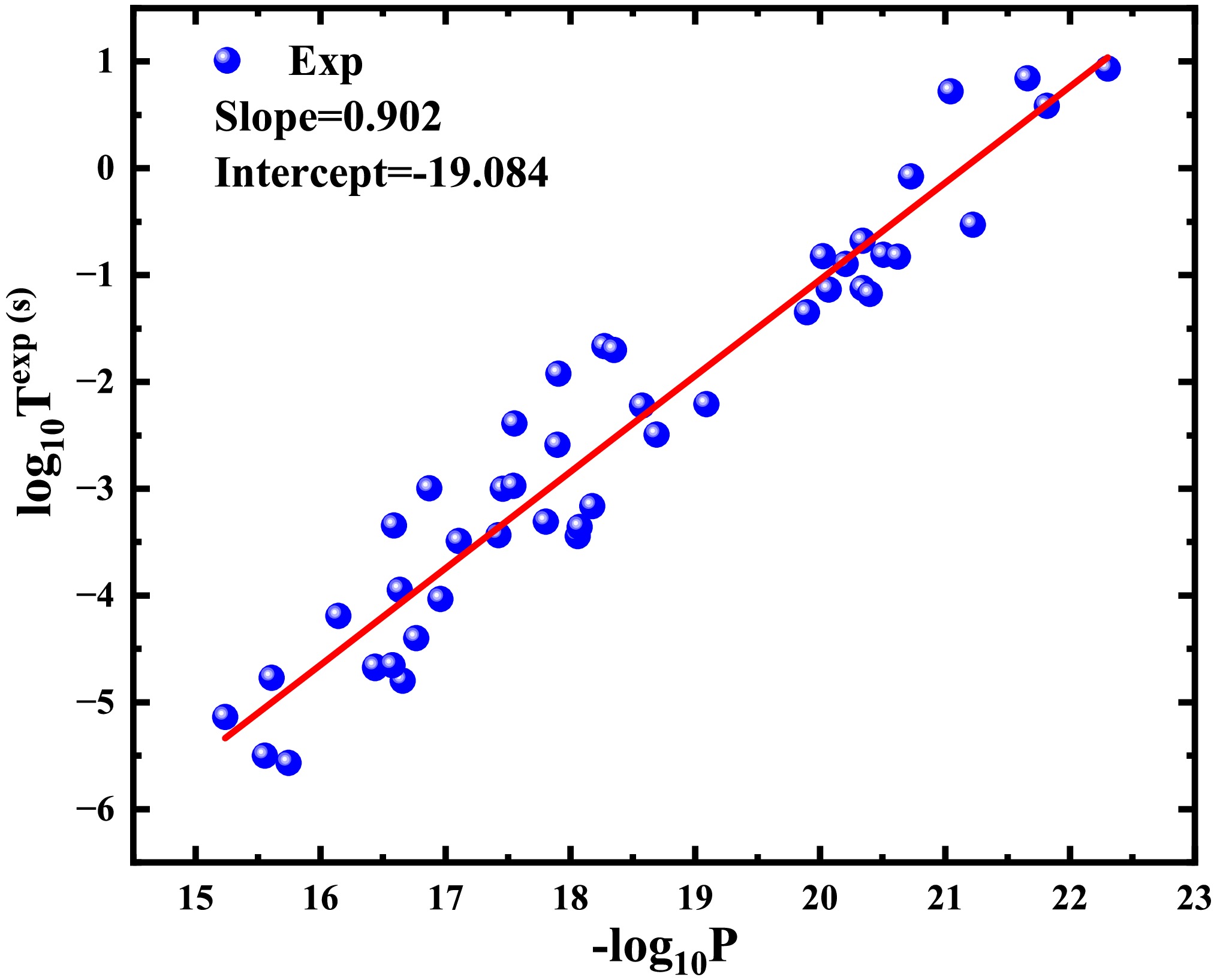

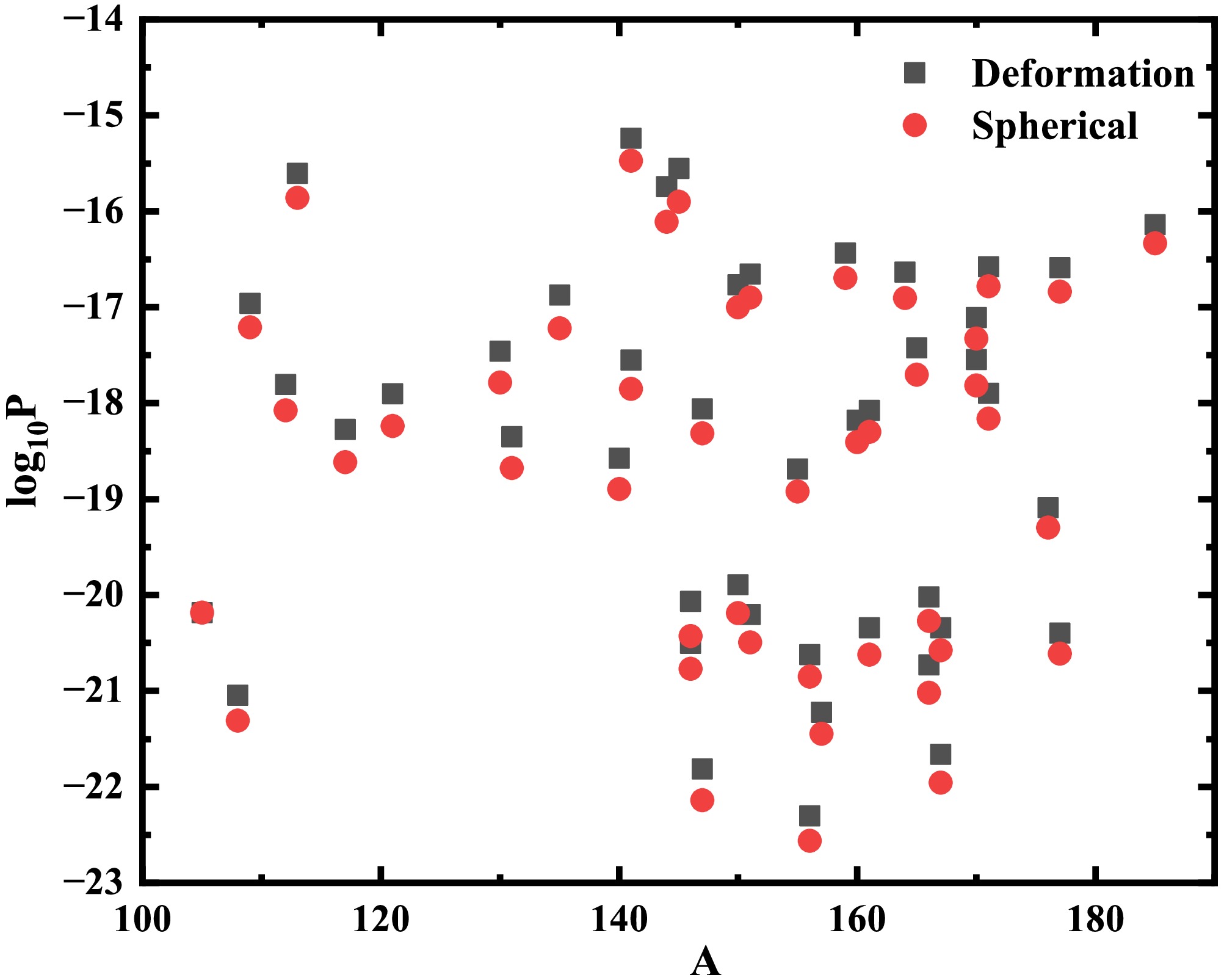

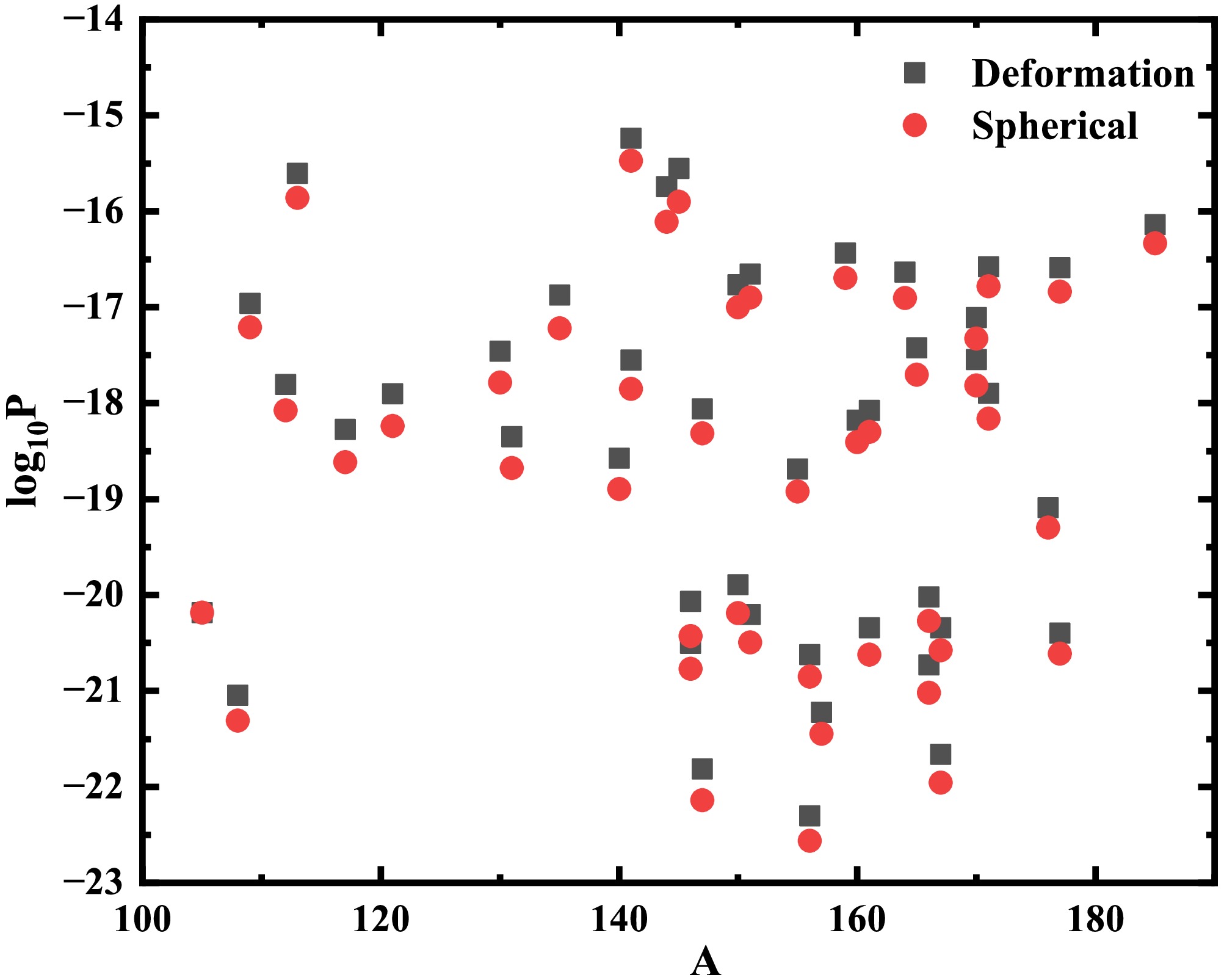

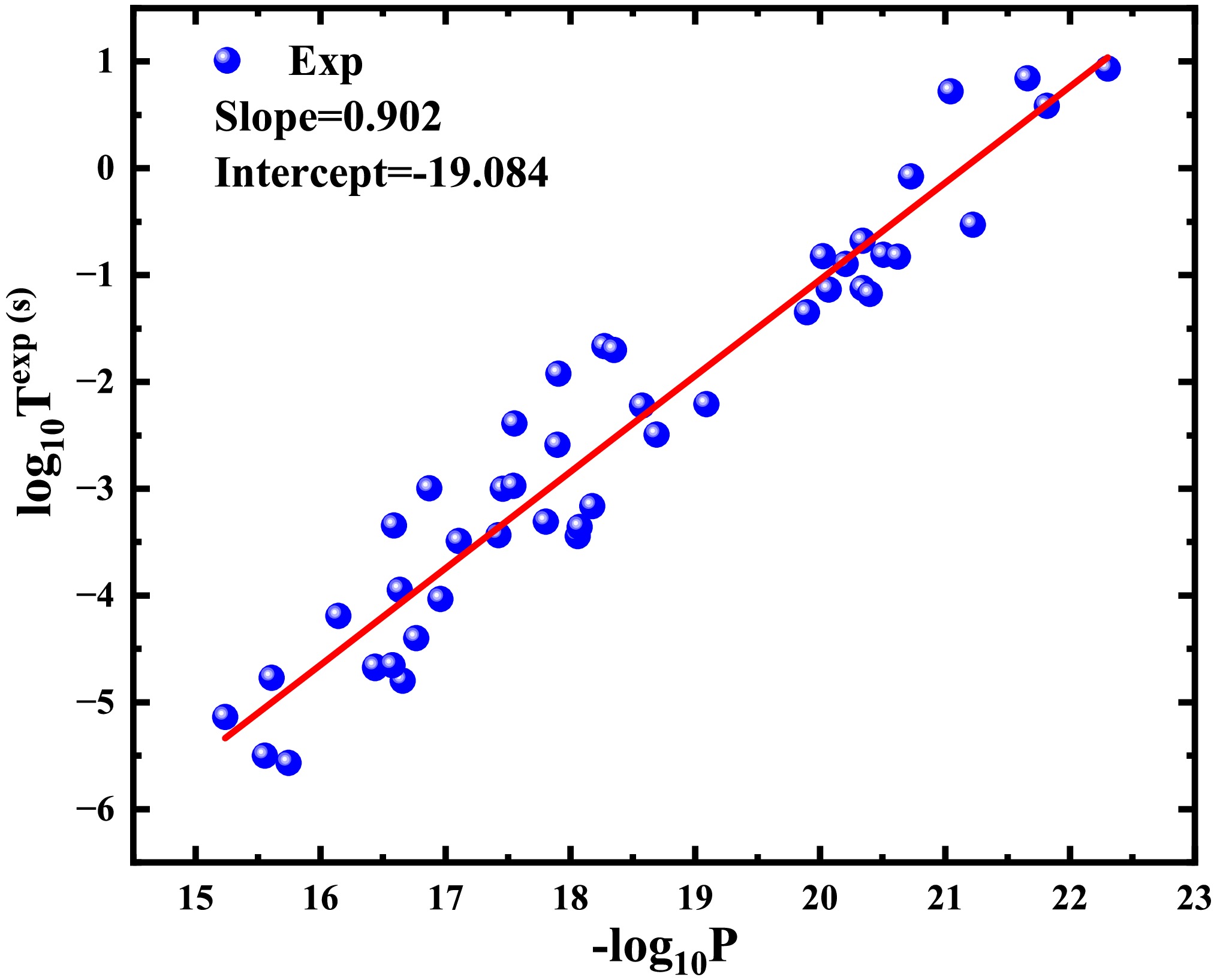

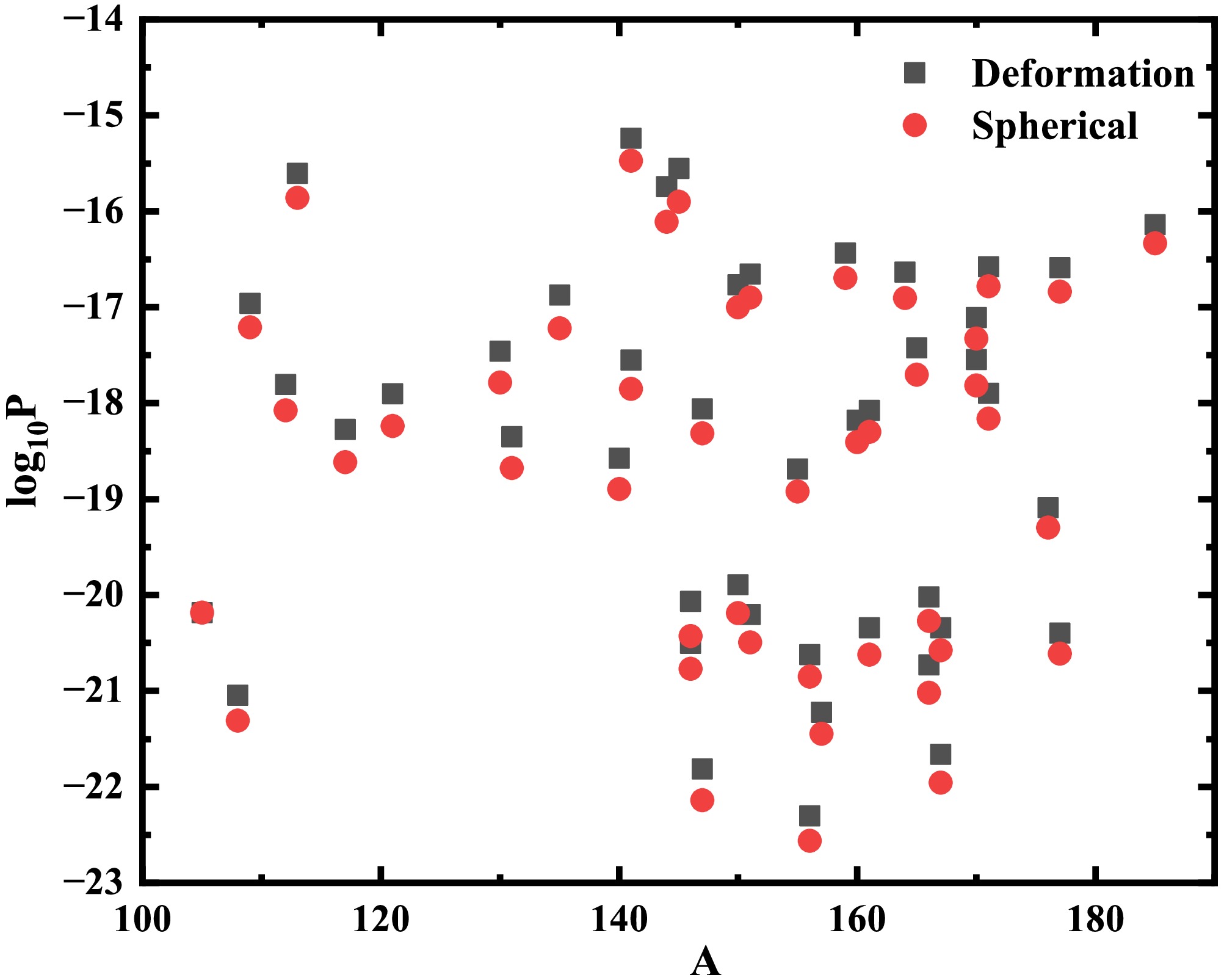

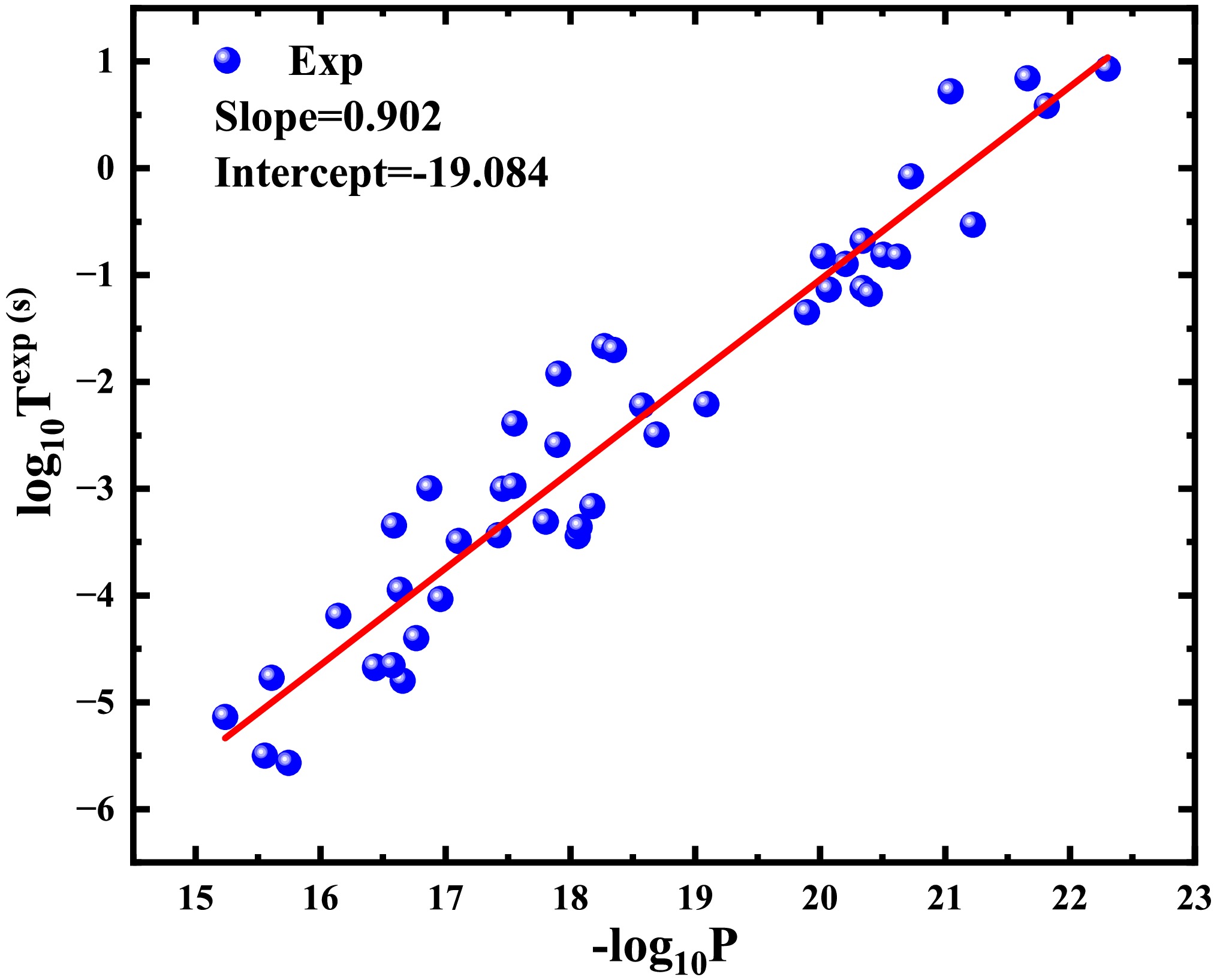

$\log_{10}T_{\rm{cal}}^i$ and$\log_{10}T_{\rm{exp}}^i$ represent the logarithmic values of the calculated and experimental half-lives of 2p radioactivity for the i-th nucleus, respectively. We adjusted the nuclear effective radius and found that when the nuclear effective radius$ r_{0} $ = 1.28 fm, the standard deviation between the experimental half-lives and calculated half-lives was minimized. The effect of the nuclear effective radius on proton radioactivity half-life is shown in Fig. 3, where a minimum point is reached at$ r_{0} $ = 1.28 fm. For true 2p radioactive nuclei, we calculated standard deviations between radioactivity half-lives obtained from the DGLM, GLDM, and Sreeja's empirical formula and the experimental data. The results are presented in Table 2. As show in the table, the standard deviation between the 2p radioactivity half-lives calculated using DGLM and those from experimental data is small. This indicates that the DGLM accurately reproduces the experimental radioactivity half-lives. For short-lived nuclei, the theoretical models fail to reliably reproduce the experimental radioactivity half-lives. This discrepancy may stem from limitations in early detection technologies and radioactive beam facilities, casting doubt on the accuracy of the data.

Figure 3. (color online) Dependence of standard deviation between theoretical and experimental half-lives on the effective nuclear radius. Minimal standard deviation is achieved at

$ r_{0} $ = 1.28 fm.DGLM GLDM Sreeja $ \sigma $

0.808 0.824 1.191 Table 2. Standard deviations between the experimental half-lives of the true 2p radioactive nuclei and the calculated values using the DGLM, GLDM, and Sreeja's empirical formula, respectively.

Given the successful performance of DGLM in describing 2p radioactivity half-lives, we applied this model to predict the 2p radioactivity half-lives that are energetically permitted but remain unmeasured in NUBASE2020 [76]. For systematic comparison, these predictions were evaluated alongside the results from other theoretical approaches, including ELDM, GLDM, and empirical formula of Sreeja, with all comparative results comprehensively tabulated in Table 3. As shown in Table 3, the 2p radioactivity half-life predictions obtained through DGLM show order-of-magnitude consistency with other theoretical predictions. This consistency highlights the strong predictive capability of DGLM in nuclear decay studies.

Nucleus $ {}^{A}Z $

l $ \log_{10}T_{1/2}(s) $

DGLM ELDM Sreeja GLDM 22Si 0 −13.292 −13.32 −12.3 −13.3 26S 0 −13.989 −13.86 −12.71 −14.59 34Ca 0 −10.174 −9.91 −8.65 −10.71 38Ti 0 −11.426 −13.56 −11.93 −14.27 39Ti 0 −0.928 −0.81 −0.28 −1.34 42Cr 0 −2.675 −2.43 −1.78 −2.88 49Ni 0 14.559 14.64 12.78 14.46 58Ge 0 −12.352 −11.74 −9.53 −13.1 59Ge 0 −6.317 −5.71 −4.44 −6.97 60Ge 0 14.256 14.62 12.4 13.55 Table 3. Predicted half-lives of 2p proton radioactivity by different models. The spins and parity are obtained from Ref. [76].

-

In this study, we calculate the half-lives of two-proton radioactivity for nuclei with atomic numbers Z=4~36 based on the DGLM. In the two-proton (2p) radioactivity, the spectroscopic factor

$ S_{\rm 2p}=G^{2}[A/(A-2)]^{2n}\chi^{2} $ [51]. Here,$ G^{2}=(2n)!/[2^{2n}(n!)^{2}] $ [69], and n represents the average principal proton oscillator quantum number given by$ n\approx(3{Z})^{1/3}-1 $ [70]. In this study,$ \chi^{2} $ =0.0143 according to a previous study by Cui et al. [71]. For a comparative analysis, our calculated radioactivity half-lives were compared with the experimental data as well as predictions from the GLDM [71] and other empirical formulas. All results are compiled in Table 1. In Table 1, the first three columns list the 2p radioactive emitters, 2p radioactivity released energy, and experimental 2p radioactivity half-lives, respectively. The last three columns present the theoretical 2p radioactivity half-lives calculated using the DGLM, GLDM, and empirical formula of Sreeja.Nucleus $ {}^{A}Z $ Q2p /MeV $ \log_{10}T_{1/2}(s) $ Exp DGLM GLDM [71] Sreeja [57] 6Be 1.371 [15] −20.30 [15] −19.83 −19.37 −21.95 12O 1.638 [20] >−20.20 [20] −18.1 −19.71 −18.47 1.820 [7] −20.94 [7] −18.38 −19.46 −18.79 1.790 [18] −20.10 [18] −18.31 −19.43 −18.74 1.800 [19] −20.12 [19] −18.32 −19.44 −18.76 16Ne 1.330 [7] −20.64 [7] −16.28 −16.45 −15.94 1.400 [17] −20.38 [17] −16.48 −16.63 −16.16 19Mg 0.750 [13] −11.40 [13] −11.50 −11.79 −10.66 45Fe 1.100 [10] −2.40 [10] −2.11 −2.23 −1.25 1.140 [9] −2.07 [9] −2.60 −2.71 −1.66 1.154 [12] −2.55 [12] −2.75 −2.87 −1.80 1.210 [72] −2.42 [72] −3.38 −3.50 −2.34 48Ni 1.290 [73] −2.52 [73] −2.58 −2.62 −1.61 1.350 [12] −2.08 [12] −3.20 −3.24 −2.13 1.310 [74] −2.52 [74] −2.79 −2.83 −1.80 54Zn 1.280 [75] −2.79 [75] −0.95 −0.87 −0.10 1.480 [11] −2.43 [11] −3.01 −2.95 −1.83 67Kr 1.690 [14] −1.70 [14] −0.81 −1.25 0.31 Table 1. 2p proton radioactivity half-lives. The experimental 2p radioactivity half-lives and decay energies were obtained from the literatures.

For a more intuitive comparison, logarithmic differences between the calculated and experimental radioactivity half-lives are presented in Fig. 2. As shown in the figure, the deviations between the calculated and experimental half-lives for true 2p radioactive nuclei fall within one order of magnitude. This indicates that the DGLM successfully reproduces the experimental 2p radioactive half-lives. The standard deviation (

$ \sigma $ ), as defined below, visually illustrates the discrepancy between the modeled half-lives and experimental results

Figure 2. (color online) Discrepancies between calculated and experimental 2p radioactivity half-lives. It encompasses both true 2p radioactivity nuclei and nuclei that do not exhibit true 2p radioactivity.

$ \begin{eqnarray} \sigma = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\sum\limits_{i=1}^N \left(\log_{10}T_{\rm{cal}}^i - \log_{10}T_{\rm{exp}}^i\right)^2} \ .\end{eqnarray} $

(13) where

$\log_{10}T_{\rm{cal}}^i$ and$\log_{10}T_{\rm{exp}}^i$ represent the logarithmic values of the calculated and experimental half-lives of 2p radioactivity for the i-th nucleus, respectively. We adjusted the nuclear effective radius and found that when the nuclear effective radius$ r_{0} $ = 1.28 fm, the standard deviation between the experimental half-lives and calculated half-lives was minimized. The effect of the nuclear effective radius on proton radioactivity half-life is shown in Fig. 3, where a minimum point is reached at$ r_{0} $ = 1.28 fm. For true 2p radioactive nuclei, we calculated standard deviations between radioactivity half-lives obtained from the DGLM, GLDM, and Sreeja's empirical formula and the experimental data. The results are presented in Table 2. As show in the table, the standard deviation between the 2p radioactivity half-lives calculated using DGLM and those from experimental data is small. This indicates that the DGLM accurately reproduces the experimental radioactivity half-lives. For short-lived nuclei, the theoretical models fail to reliably reproduce the experimental radioactivity half-lives. This discrepancy may stem from limitations in early detection technologies and radioactive beam facilities, casting doubt on the accuracy of the data.

Figure 3. (color online) Dependence of standard deviation between theoretical and experimental half-lives on the effective nuclear radius. Minimal standard deviation is achieved at

$ r_{0} $ = 1.28 fm.DGLM GLDM Sreeja $ \sigma $ 0.808 0.824 1.191 Table 2. Standard deviations between the experimental half-lives of the true 2p radioactive nuclei and the calculated values using the DGLM, GLDM, and Sreeja's empirical formula, respectively.

Given the successful performance of DGLM in describing 2p radioactivity half-lives, we applied this model to predict the 2p radioactivity half-lives that are energetically permitted but remain unmeasured in NUBASE2020 [76]. For systematic comparison, these predictions were evaluated alongside the results from other theoretical approaches, including ELDM, GLDM, and empirical formula of Sreeja, with all comparative results comprehensively tabulated in Table 3. As shown in Table 3, the 2p radioactivity half-life predictions obtained through DGLM show order-of-magnitude consistency with other theoretical predictions. This consistency highlights the strong predictive capability of DGLM in nuclear decay studies.

Nucleus $ {}^{A}Z $ l $ \log_{10}T_{1/2}(s) $ DGLM ELDM Sreeja GLDM 22Si 0 −13.292 −13.32 −12.3 −13.3 26S 0 −13.989 −13.86 −12.71 −14.59 34Ca 0 −10.174 −9.91 −8.65 −10.71 38Ti 0 −11.426 −13.56 −11.93 −14.27 39Ti 0 −0.928 −0.81 −0.28 −1.34 42Cr 0 −2.675 −2.43 −1.78 −2.88 49Ni 0 14.559 14.64 12.78 14.46 58Ge 0 −12.352 −11.74 −9.53 −13.1 59Ge 0 −6.317 −5.71 −4.44 −6.97 60Ge 0 14.256 14.62 12.4 13.55 Table 3. Predicted half-lives of 2p proton radioactivity by different models. The spins and parity are obtained from Ref. [76].

-

In this work, we calculate half-lives of two-proton radioactivity for nuclei with atomic numbers Z=4~36 based on the DGLM. In the two-proton (2p) radioactivity, the spectroscopic factor

$ S_{\rm 2p}=G^{2}[A/(A-2)]^{2n}\chi^{2} $ [51]. Here$ G^{2}=(2n)!/[2^{2n}(n!)^{2}] $ [77], and n is the average principal proton oscillator quantum number given by$ n\approx(3{Z})^{1/3}-1 $ [78]. In this study,$ \chi^{2} $ =0.0143, according to a previous study by Cui et al. [79]. For comparative analysis, our calculated radioactivity half-lives were compared with the experimental data as well as predictions from the generalized liquid drop model(GLDM) [79] and other empirical formulas. All results are compiled in Table 1. In Table 1, the first three columns list the 2p radioactive emitters, the 2p radioactivity released energy, and the experimental 2p radioactivity half-lives, respectively. The last three columns present the theoretical 2p radioactivity half-lives calculated using the DGLM, the GLDM, and empirical formula of Sreeja.Nucleus $ {}^{A}Z $

Q2p MeV $ \log_{10}T_{1/2}(s) $

Exp DGLM GLDM [79] Sreeja [57] 6Be 1.371 [15] −20.30 [15] −19.83 −19.37 −21.95 12O 1.638 [20] >−20.20 [20] −18.1 −19.71 −18.47 1.820 [7] −20.94 [7] −18.38 −19.46 −18.79 1.790 [18] −20.10 [18] −18.31 −19.43 −18.74 1.800 [19] −20.12 [19] −18.32 −19.44 −18.76 16Ne 1.330 [7] −20.64 [7] −16.28 −16.45 −15.94 1.400 [17] −20.38 [17] −16.48 −16.63 −16.16 19Mg 0.750 [13] −11.40 [13] −11.50 −11.79 −10.66 45Fe 1.100 [10] −2.40 [10] −2.11 −2.23 −1.25 1.140 [9] −2.07 [9] −2.60 −2.71 −1.66 1.154 [12] −2.55 [12] −2.75 −2.87 −1.80 1.210 [80] −2.42 [80] −3.38 −3.50 −2.34 48Ni 1.290 [81] −2.52 [81] −2.58 −2.62 −1.61 1.350 [12] −2.08 [12] −3.20 −3.24 −2.13 1.310 [82] −2.52 [82] −2.79 −2.83 −1.80 54Zn 1.280 [83] −2.79 [83] −0.95 −0.87 −0.10 1.480 [11] −2.43 [11] −3.01 −2.95 −1.83 67Kr 1.690 [14] −1.70 [14] −0.81 −1.25 0.31 Table 1. The 2p proton radioactivity half-lives. The experimental 2p radioactivity half-lives and decay energies were obtained from the literatures.

For a more intuitive comparison, the logarithmic differences between the calculated and experimental radioactivity half-lives are presented in Figure 2. As shown in the figure, the deviations between the calculated and experimental half-lives for true 2p radioactive nuclei fall within one order of magnitude. This indicates that the DGLM successfully reproduces the experimental 2p radioactive half-lives. The standard deviation (

$ \sigma $ ), as defined below, visually illustrates the discrepancy between modeled half-lives and experimental results

Figure 2. (Color online) Discrepancies between calculated and experimental 2p radioactivity half-lives. It encompasses both true 2p radioactivity nuclei and nuclei that do not exhibit true 2p radioactivity.

$ \begin{eqnarray} \sigma = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\sum\limits_{i=1}^N \left(\log_{10}T_{\rm{cal}}^i - \log_{10}T_{\rm{exp}}^i\right)^2} \end{eqnarray} $

(13) Here,

$\log_{10}T_{\rm{cal}}^i$ and$\log_{10}T_{\rm{exp}}^i$ represent the logarithmic values of the calculated and experimental half-lives of 2p radioactivity for the i-th nucleus, respectively. We adjusted the nuclear effective radius and found that when the nuclear effective radius$ r_{0} $ = 1.28 fm, the standard deviation between the experimental half-lives and calculated half-lives is minimized. The influence of the nuclear effective radius on proton radioactivity half-life is shown in Figure 3, where a minimum point is reached at$ r_{0} $ = 1.28 fm. For true 2p radioactive nuclei, we calculated the standard deviations between the radioactivity half-lives obtained from the DGLM, GLDM, and Sreeja's empirical formula, and the experimental data. The results are presented in Table 2. As show in the table, the standard deviation between the 2p radioactivity half-lives calculated using DGLM and those from experimental data is small. This indicate that the DGLM accurately reproduces the experimental radioactivity half-lives. It is noteworthy that for short-lived nuclei, the theoretical models fail to reliably reproduce the experimental radioactivity half-lives. This discrepancy may stem from limitations in early detection technologies and radioactive beam facilities, casting doubt on the accuracy of the data.

Figure 3. (Color online) Dependence of the standard deviation between theoretical and experimental half-lives on the effective nuclear radius. Minimal standard deviation is achieved at

$ r_{0} $ =1.28fm.DGLM GLDM Sreeja $ \sigma $

0.808 0.824 1.191 Table 2. Standard deviations between the experimental half-lives of the true 2p radioactive nuclei and the calculated values using the DGLM, GLDM, and Sreeja, respectively.

Given the DGLM's successful performance in describing 2p radioactivity half-lives, we applied this model to predict the 2p radioactivity half-lives that are energetically permitted but remain unmeasured in NUBASE2020 [86]. For systematic comparison, these predictions were evaluated alongside result form other theoretical approaches, including the ELDM, GLDM, and empirical formula of Sreeja, with all comparative results comprehensively tabulated in Table 3. As shown in Table 3, the 2p radioactivity half-life predictions obtained through DGLM show order-of-magnitude consistency with other theoretical predictions. This consistency highlights the strong predictive capability of DGLM in nuclear decay studies.

Nucleus $ {}^{A}Z $

l $ \log_{10}T_{1/2}(s) $

DGLM ELDM Sreeja GLDM 22Si 0 −13.292 −13.32 −12.3 −13.3 26S 0 −13.989 −13.86 −12.71 −14.59 34Ca 0 −10.174 −9.91 −8.65 −10.71 38Ti 0 −11.426 −13.56 −11.93 −14.27 39Ti 0 −0.928 −0.81 −0.28 −1.34 42Cr 0 −2.675 −2.43 −1.78 −2.88 49Ni 0 14.559 14.64 12.78 14.46 58Ge 0 −12.352 −11.74 −9.53 −13.1 59Ge 0 −6.317 −5.71 −4.44 −6.97 60Ge 0 14.256 14.62 12.4 13.55 Table 3. The predicted half-lives of 2p proton radioactivity by different models. The spins and parity are obtained from Ref. [86].

-

In this study, we calculate the half-lives of two-proton radioactivity for nuclei with atomic numbers Z=4~36 based on the DGLM. In the two-proton (2p) radioactivity, the spectroscopic factor

$ S_{\rm 2p}=G^{2}[A/(A-2)]^{2n}\chi^{2} $ [51]. Here,$ G^{2}=(2n)!/[2^{2n}(n!)^{2}] $ [69], and n represents the average principal proton oscillator quantum number given by$ n\approx(3{Z})^{1/3}-1 $ [70]. In this study,$ \chi^{2} $ =0.0143 according to a previous study by Cui et al. [71]. For a comparative analysis, our calculated radioactivity half-lives were compared with the experimental data as well as predictions from the GLDM [71] and other empirical formulas. All results are compiled in Table 1. In Table 1, the first three columns list the 2p radioactive emitters, 2p radioactivity released energy, and experimental 2p radioactivity half-lives, respectively. The last three columns present the theoretical 2p radioactivity half-lives calculated using the DGLM, GLDM, and empirical formula of Sreeja.Nucleus $ {}^{A}Z $ Q2p /MeV $ \log_{10}T_{1/2}(s) $ Exp DGLM GLDM [71] Sreeja [57] 6Be 1.371 [15] −20.30 [15] −19.83 −19.37 −21.95 12O 1.638 [20] >−20.20 [20] −18.1 −19.71 −18.47 1.820 [7] −20.94 [7] −18.38 −19.46 −18.79 1.790 [18] −20.10 [18] −18.31 −19.43 −18.74 1.800 [19] −20.12 [19] −18.32 −19.44 −18.76 16Ne 1.330 [7] −20.64 [7] −16.28 −16.45 −15.94 1.400 [17] −20.38 [17] −16.48 −16.63 −16.16 19Mg 0.750 [13] −11.40 [13] −11.50 −11.79 −10.66 45Fe 1.100 [10] −2.40 [10] −2.11 −2.23 −1.25 1.140 [9] −2.07 [9] −2.60 −2.71 −1.66 1.154 [12] −2.55 [12] −2.75 −2.87 −1.80 1.210 [72] −2.42 [72] −3.38 −3.50 −2.34 48Ni 1.290 [73] −2.52 [73] −2.58 −2.62 −1.61 1.350 [12] −2.08 [12] −3.20 −3.24 −2.13 1.310 [74] −2.52 [74] −2.79 −2.83 −1.80 54Zn 1.280 [75] −2.79 [75] −0.95 −0.87 −0.10 1.480 [11] −2.43 [11] −3.01 −2.95 −1.83 67Kr 1.690 [14] −1.70 [14] −0.81 −1.25 0.31 Table 1. 2p proton radioactivity half-lives. The experimental 2p radioactivity half-lives and decay energies were obtained from the literatures.

For a more intuitive comparison, logarithmic differences between the calculated and experimental radioactivity half-lives are presented in Fig. 2. As shown in the figure, the deviations between the calculated and experimental half-lives for true 2p radioactive nuclei fall within one order of magnitude. This indicates that the DGLM successfully reproduces the experimental 2p radioactive half-lives. The standard deviation (

$ \sigma $ ), as defined below, visually illustrates the discrepancy between the modeled half-lives and experimental results

Figure 2. (color online) Discrepancies between calculated and experimental 2p radioactivity half-lives. It encompasses both true 2p radioactivity nuclei and nuclei that do not exhibit true 2p radioactivity.

$ \begin{eqnarray} \sigma = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\sum\limits_{i=1}^N \left(\log_{10}T_{\rm{cal}}^i - \log_{10}T_{\rm{exp}}^i\right)^2} \ .\end{eqnarray} $

(13) where