-

Detectable signals from mergers of compact stars, such as those involving black holes and neutron stars, provide insights into their internal composition and dynamic evolution, thereby opening a new avenue for astronomical outreach. Fortunately, the detection of binary neutron star (BNS) mergers by the LIGO-Virgo Collaboration and electromagnetic (EM) observer partners, GW170817 [1], has imposed new limitations on the maximum mass of neutron stars (NSs). In addition, it significantly influences our understanding of gravity, specifically the physics of dense matter above

$ \sim $ 1-2$ n_0 $ (being$ n_0 = 0.16 $ fm$ ^{-3} $ the nuclear saturation density). Therefore, accurately characterizing the equation of state (EOS) of dense matter is still challenging when attempting to infer the interior composition of neutron stars (NSs). Among the various proposed interior structures discussed in the literature, the quark star (QS), which comprises quark matter, has emerged as a potential candidate. Therefore, QSs in such environments offer a platform for investigating high-density matter beyond nuclear saturation.Theoretically, quark matter (QM) treated as the true ground state of dense matter was proposed by E. Witten in 1984 [2] (following Bodmer's important precursor [3]). The hypothesis concerning QM and particularly strange QM consisting of u, d, and s quarks, also called strange quark matter (SQM), posits that it represents the most energetically favourable state of matter. However, some research [4, 5] has explored the flavor-dependent effects of quark gas on the QCD vacuum, suggesting that

$ u, d $ quark matter ($ ud\mathrm{QM} $ ) is typically more stable than SQM. Notably, at sufficiently high baryon numbers,$ ud\mathrm{QM} $ can surpass the stability of ordinary nuclei and extend beyond the periodic table. This finding has led to an increase in recent experimental pursuits [6−8] and phenomenological research [9−14].Along these lines, the MIT bag model [15] has been widely employed by many authors to describe massive neutron stars (NSs), i.e., NSs with a quark matter core, which have been detected in the past decade [16−19]. A modified version of this model, incorporating vector interactions and drawing features from quantum hadrodynamics (QHD) [20], has also been proposed and applied to strange quark matter (SQM) and quark stars [21−24]. Building on these developments, Zhang et al [25] introduced an EoS for quark matter that incorporates perturbative QCD (pQCD) corrections and color superconductivity. This model has the notable advantage of producing massive quark stars with larger radii consistent with recent astrophysical constraints. An additional feature is that, through a single parameter, the EoS can be rescaled into a dimensionless form, thereby reducing the number of free parameters and characterizing the relative strength of strong interaction effects [26−28].

However, in the presence of enormous densities and pressures in the interiors of such stars, one can expect that the pressure could be anisotropic, with the radial pressure differing from that in the azimuthal directions. In addition to these nuclear interactions [30], viscosity effects [31], pion condensation [32], and some kinds of phase transitions [33] may contribute to the presence of pressure anisotropy. Considering local anisotropy, QSs or NSs have been studied to extract information regarding their internal structure and nuclear physics(see, e.g., [34−45]). These investigations suggest that pressure anisotropy has a significant impact on the mass-radius relationship and the internal properties of stars, including the maximum surface redshift and maximum compactness. It's also important to note that the presence of anisotropy influences the stability of the configuration by supporting outwardly increasing energy density within the star core [46].

The above discussion suggests that investigations of anisotropic systems are typically conducted within the framework of Einstein's theory of gravity. Here, we study the stability of anisotropic QSs in gravity's rainbow. Gravity's rainbow [47] has been treated as an extension of the principles of doubly special relativity (DSR) [48] to curved spacetimes. This theory suggests a modification of the spacetime metric by introducing energy-dependent rainbow functions,

$ \Xi(x) $ and$ \Sigma(x) $ , that are characterised by the dimensionless ratio of the total energy of the probe particle E to the Planck energy$ E_p $ . This approach helps alter the relativistic dispersion relations. It allows for a deeper understanding of the relation between quantum mechanics and general relativity at high energy scales, particularly near the Planck scale [49, 50]. By incorporating energy-dependent effects into curved spacetimes, gravity's rainbow attempts to address some of the conceptual issues, like black hole solutions and their properties [51−56], gravastar, and wormhole solutions [57, 58]. Another intriguing finding in this context is the dark star [59] and NSs [60], which also analyse their stability-related issues.In summary, this work thoroughly investigates the possible existence of QSs with pressure anisotropy, emphasizing the interaction between strongly interacting quark matter and gravity's rainbow, where strongly interacting quark matter is considered. Focusing on understanding how these concepts affect the stability and detectability of QSs, and building upon recent theoretical works, we aim to gain a collective understanding of their fundamental properties. Inside these stars, the EoS strongly influences maximum mass and drives their internal structure, and it is susceptible to the strong interactions of quark matter. Conversely, Gravity's Rainbow alters the gravitational field at high energies, leading to modifications in compactness and, therefore, in the observational properties of the QSs. The theory of gravity and high matter interactions is varied in an attempt to study their combined effects on mass-radius relations, pulsar emissions, and gravitational wave signatures. Furthermore, it contributes to the knowledge of these constructs in broad astrophysics. This helps us even if we do not know the correct model yet, since it has some ideas for testing quantum gravity models in extreme astrophysical environments. In this work, we investigate the properties of QSs with modified parameters and anisotropic pressures within Gravity's Rainbow, focusing on their internal structure and stability in response to perturbations. Although the study by Zhang and Mann [25] provides a unified EoS for isotropic interacting quark matter (IQM) and discusses the corresponding QS solutions within general relativity, our work presents an important extension in two directions: First, we consider pressure anisotropy in the stellar matter configuration, which is physically motivated in ultra-dense regimes due to strong interaction effects, viscosity, or phase transitions; second, we introduce gravity's rainbow formalism by modifying spacetime geometry via energy-dependent rainbow functions that can capture possible Lorentz-violating effects at high energies. With this combined framework, we investigate how anisotropic pressures and quantum gravity-inspired corrections jointly impact the mass-radius relation, compactness, and stability criteria of quark stars, extending the description beyond what conventional isotropic models can achieve.

This paper is structured in the following manner: In Sec. II, we provide a detailed description of the perturbative QCD-motivated EoS, and the derivation of the modified Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff (TOV) equations is also included. In Sec. III, we present the results of the numerical computation, illustrating the impact of the model parameters on the mass-radius relationships. Sec. IV comprehensively examines the static stability criterion, adiabatic index, and sound velocity. Finally, we discuss the results in Sec. V.

-

Detectable signals from mergers of compact stars, such as those involving black holes and neutron stars (NSs), provide insights into their internal composition and dynamic evolution, thereby opening a new avenue for astronomical outreach. Fortunately, the detection of binary NS (BNS) mergers by the LIGO-Virgo Collaboration and electromagnetic (EM) observer partners, such as GW170817 [1], has imposed new limitations on the maximum mass of NSs. In addition, it significantly influences our understanding of gravity, specifically, the physics of dense matter above

$ \sim $ 1-2$ n_0 $ ($ n_0 = 0.16 $ fm$ ^{-3} $ represents the nuclear saturation density). Therefore, accurately characterizing the equation of state (EOS) of dense matter is still challenging when attempting to infer the interior composition of NSs. Among the various proposed interior structures discussed in literature, the quark star (QS), which comprises quark matter, has emerged as a potential candidate. Therefore, QSs in such environments offer a platform for investigating high-density matter beyond nuclear saturation.Theoretically, quark matter (QM) treated as the true ground state of dense matter was proposed by E. Witten in 1984 [2] (following Bodmer's important precursor [3]). The hypothesis concerning QM and particularly strange QM consisting of u, d, and s quarks, also called strange quark matter (SQM), posits that it represents the most energetically favorable state of matter. However, some studies [4, 5] have explored the flavor-dependent effects of quark gas on the QCD vacuum, suggesting that

$ u, d $ quark matter ($ u{\rm d}\mathrm{QM} $ ) is typically more stable than SQM. Notably, at sufficiently high baryon numbers,$ u{\rm d}\mathrm{QM} $ can surpass the stability of ordinary nuclei and extend beyond the periodic table. This finding has led to an increase in recent experimental pursuits [6−8] and phenomenological research [9−14].Along these lines, the MIT bag model [15] has been widely employed by several authors to describe massive NSs, i.e., NSs with a quark matter core, which have been detected in the past decade [16−19]. A modified version of this model, incorporating vector interactions and drawing features from quantum hadrodynamics (QHD) [20], has also been proposed and applied to SQM and QSs [21−24]. Building on these developments, Zhang et al. [25] introduced an EoS for QM that incorporates perturbative quantum chromodynamics (QCD) (pQCD) corrections and color superconductivity. This model has the notable advantage of producing massive QSs with larger radii consistent with recent astrophysical constraints. An additional feature is that, through a single parameter, the EoS can be rescaled into a dimensionless form, thereby reducing the number of free parameters and characterizing the relative strength of strong interaction effects [26−28].

However, in the presence of enormous densities and pressures in the interiors of such stars, one can expect that the pressure could be anisotropic, with the radial pressure differing from that in the azimuthal directions. In addition to these nuclear interactions [29], viscosity effects [30], pion condensation [31], and some kinds of phase transitions [32] may contribute to the presence of pressure anisotropy. Considering local anisotropy, QSs or NSs have been studied to extract information regarding their internal structure and nuclear physics (see, e.g., [33−44]). These investigations suggest that pressure anisotropy has a significant influence on the mass-radius relationship and the internal properties of stars, including the maximum surface redshift and maximum compactness. Note that the presence of anisotropy influences the stability of the configuration by supporting outwardly increasing energy density within the star core [45].

The above discussion suggests that investigations of anisotropic systems are typically conducted within the framework of Einstein's theory of gravity. Here, we study the stability of anisotropic QSs in gravity's rainbow. Gravity's rainbow [46] has been treated as an extension of the principles of doubly special relativity (DSR) [47] to curved spacetimes. This theory suggests a modification of the spacetime metric by introducing energy-dependent rainbow functions,

$ \Xi(x) $ and$ \Sigma(x) $ , which are characterized by the dimensionless ratio of the total energy of the probe particle E to the Planck energy$ E_p $ . This approach helps alter the relativistic dispersion relations. It allows for a deeper understanding of the relation between quantum mechanics and general relativity at high energy scales, particularly near the Planck scale [48, 49]. By incorporating energy-dependent effects into curved spacetimes, gravity's rainbow attempts to address some of the conceptual issues, such as black hole solutions and their properties [50−55], gravastars, and wormhole solutions [56, 57]. Other intriguing findings in this context are the studies on dark star [58] and NSs [59], which also analyze their stability-related issues.In summary, this study thoroughly investigates the possible existence of QSs with pressure anisotropy, emphasizing the interaction between strongly interacting QM and gravity's rainbow, where strongly interacting QM is considered. Focusing on understanding how these concepts affect the stability and detectability of QSs, and building upon recent theoretical works, we aim to gain a collective understanding of their fundamental properties. Inside these stars, the EoS strongly influences maximum mass and drives their internal structure, and it is susceptible to the strong interactions of QM. Conversely, gravity's rainbow alters the gravitational field at high energies, leading to modifications in compactness and, therefore, in the observational properties of the QSs. The theory of gravity and high matter interactions is varied in an attempt to study their combined effects on mass-radius relations, pulsar emissions, and gravitational wave signatures. Furthermore, it contributes to the knowledge of these constructs in broad astrophysics. This helps us even if we do not know the correct model yet, as it has some ideas for testing quantum gravity models in extreme astrophysical environments. In this study, we investigate the properties of QSs with modified parameters and anisotropic pressures within gravity's rainbow, focusing on their internal structure and stability in response to perturbations. Although the study by Zhang and Mann [25] provides a unified EoS for isotropic interacting QM and discusses the corresponding QS solutions within general relativity, our study presents an important extension in two directions: First, we consider pressure anisotropy in the stellar matter configuration, which is physically motivated in ultra-dense regimes owing to strong interaction effects, viscosity, or phase transitions; second, we introduce the gravity's rainbow formalism by modifying spacetime geometry via energy-dependent rainbow functions that can capture possible Lorentz-violating effects at high energies. With this combined framework, we investigate how anisotropic pressures and quantum gravity-inspired corrections jointly influence the mass-radius relation, compactness, and stability criteria of QSs, extending the description beyond what conventional isotropic models can achieve.

The remainder of this paper is structured in the following manner. In Sec. II, we provide a detailed description of the perturbative QCD-motivated EoS, and the derivation of the modified Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff (TOV) equations is also included. In Sec. III, we present the results of the numerical computation, illustrating the influence of the model parameters on the mass-radius relationships. Sec. IV comprehensively examines the static stability criterion, adiabatic index, and sound velocity. Finally, we discuss the results in Sec. V.

-

Detectable signals from mergers of compact stars, such as those involving black holes and neutron stars (NSs), provide insights into their internal composition and dynamic evolution, thereby opening a new avenue for astronomical outreach. Fortunately, the detection of binary NS (BNS) mergers by the LIGO-Virgo Collaboration and electromagnetic (EM) observer partners, such as GW170817 [1], has imposed new limitations on the maximum mass of NSs. In addition, it significantly influences our understanding of gravity, specifically, the physics of dense matter above

$ \sim $ 1-2$ n_0 $ ($ n_0 = 0.16 $ fm$ ^{-3} $ represents the nuclear saturation density). Therefore, accurately characterizing the equation of state (EOS) of dense matter is still challenging when attempting to infer the interior composition of NSs. Among the various proposed interior structures discussed in literature, the quark star (QS), which comprises quark matter, has emerged as a potential candidate. Therefore, QSs in such environments offer a platform for investigating high-density matter beyond nuclear saturation.Theoretically, quark matter (QM) treated as the true ground state of dense matter was proposed by E. Witten in 1984 [2] (following Bodmer's important precursor [3]). The hypothesis concerning QM and particularly strange QM consisting of u, d, and s quarks, also called strange quark matter (SQM), posits that it represents the most energetically favorable state of matter. However, some studies [4, 5] have explored the flavor-dependent effects of quark gas on the QCD vacuum, suggesting that

$ u, d $ quark matter ($ u{\rm d}\mathrm{QM} $ ) is typically more stable than SQM. Notably, at sufficiently high baryon numbers,$ u{\rm d}\mathrm{QM} $ can surpass the stability of ordinary nuclei and extend beyond the periodic table. This finding has led to an increase in recent experimental pursuits [6−8] and phenomenological research [9−14].Along these lines, the MIT bag model [15] has been widely employed by several authors to describe massive NSs, i.e., NSs with a quark matter core, which have been detected in the past decade [16−19]. A modified version of this model, incorporating vector interactions and drawing features from quantum hadrodynamics (QHD) [20], has also been proposed and applied to SQM and QSs [21−24]. Building on these developments, Zhang et al. [25] introduced an EoS for QM that incorporates perturbative quantum chromodynamics (QCD) (pQCD) corrections and color superconductivity. This model has the notable advantage of producing massive QSs with larger radii consistent with recent astrophysical constraints. An additional feature is that, through a single parameter, the EoS can be rescaled into a dimensionless form, thereby reducing the number of free parameters and characterizing the relative strength of strong interaction effects [26−28].

However, in the presence of enormous densities and pressures in the interiors of such stars, one can expect that the pressure could be anisotropic, with the radial pressure differing from that in the azimuthal directions. In addition to these nuclear interactions [29], viscosity effects [30], pion condensation [31], and some kinds of phase transitions [32] may contribute to the presence of pressure anisotropy. Considering local anisotropy, QSs or NSs have been studied to extract information regarding their internal structure and nuclear physics (see, e.g., [33−44]). These investigations suggest that pressure anisotropy has a significant influence on the mass-radius relationship and the internal properties of stars, including the maximum surface redshift and maximum compactness. Note that the presence of anisotropy influences the stability of the configuration by supporting outwardly increasing energy density within the star core [45].

The above discussion suggests that investigations of anisotropic systems are typically conducted within the framework of Einstein's theory of gravity. Here, we study the stability of anisotropic QSs in gravity's rainbow. Gravity's rainbow [46] has been treated as an extension of the principles of doubly special relativity (DSR) [47] to curved spacetimes. This theory suggests a modification of the spacetime metric by introducing energy-dependent rainbow functions,

$ \Xi(x) $ and$ \Sigma(x) $ , which are characterized by the dimensionless ratio of the total energy of the probe particle E to the Planck energy$ E_p $ . This approach helps alter the relativistic dispersion relations. It allows for a deeper understanding of the relation between quantum mechanics and general relativity at high energy scales, particularly near the Planck scale [48, 49]. By incorporating energy-dependent effects into curved spacetimes, gravity's rainbow attempts to address some of the conceptual issues, such as black hole solutions and their properties [50−55], gravastars, and wormhole solutions [56, 57]. Other intriguing findings in this context are the studies on dark star [58] and NSs [59], which also analyze their stability-related issues.In summary, this study thoroughly investigates the possible existence of QSs with pressure anisotropy, emphasizing the interaction between strongly interacting QM and gravity's rainbow, where strongly interacting QM is considered. Focusing on understanding how these concepts affect the stability and detectability of QSs, and building upon recent theoretical works, we aim to gain a collective understanding of their fundamental properties. Inside these stars, the EoS strongly influences maximum mass and drives their internal structure, and it is susceptible to the strong interactions of QM. Conversely, gravity's rainbow alters the gravitational field at high energies, leading to modifications in compactness and, therefore, in the observational properties of the QSs. The theory of gravity and high matter interactions is varied in an attempt to study their combined effects on mass-radius relations, pulsar emissions, and gravitational wave signatures. Furthermore, it contributes to the knowledge of these constructs in broad astrophysics. This helps us even if we do not know the correct model yet, as it has some ideas for testing quantum gravity models in extreme astrophysical environments. In this study, we investigate the properties of QSs with modified parameters and anisotropic pressures within gravity's rainbow, focusing on their internal structure and stability in response to perturbations. Although the study by Zhang and Mann [25] provides a unified EoS for isotropic interacting QM and discusses the corresponding QS solutions within general relativity, our study presents an important extension in two directions: First, we consider pressure anisotropy in the stellar matter configuration, which is physically motivated in ultra-dense regimes owing to strong interaction effects, viscosity, or phase transitions; second, we introduce the gravity's rainbow formalism by modifying spacetime geometry via energy-dependent rainbow functions that can capture possible Lorentz-violating effects at high energies. With this combined framework, we investigate how anisotropic pressures and quantum gravity-inspired corrections jointly influence the mass-radius relation, compactness, and stability criteria of QSs, extending the description beyond what conventional isotropic models can achieve.

The remainder of this paper is structured in the following manner. In Sec. II, we provide a detailed description of the perturbative QCD-motivated EoS, and the derivation of the modified Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff (TOV) equations is also included. In Sec. III, we present the results of the numerical computation, illustrating the influence of the model parameters on the mass-radius relationships. Sec. IV comprehensively examines the static stability criterion, adiabatic index, and sound velocity. Finally, we discuss the results in Sec. V.

-

Detectable signals from mergers of compact stars, such as those involving black holes and neutron stars (NSs), provide insights into their internal composition and dynamic evolution, thereby opening a new avenue for astronomical outreach. Fortunately, the detection of binary NS (BNS) mergers by the LIGO-Virgo Collaboration and electromagnetic (EM) observer partners, such as GW170817 [1], has imposed new limitations on the maximum mass of NSs. In addition, it significantly influences our understanding of gravity, specifically, the physics of dense matter above

$ \sim $ 1-2$ n_0 $ ($ n_0 = 0.16 $ fm$ ^{-3} $ represents the nuclear saturation density). Therefore, accurately characterizing the equation of state (EOS) of dense matter is still challenging when attempting to infer the interior composition of NSs. Among the various proposed interior structures discussed in literature, the quark star (QS), which comprises quark matter, has emerged as a potential candidate. Therefore, QSs in such environments offer a platform for investigating high-density matter beyond nuclear saturation.Theoretically, quark matter (QM) treated as the true ground state of dense matter was proposed by E. Witten in 1984 [2] (following Bodmer's important precursor [3]). The hypothesis concerning QM and particularly strange QM consisting of u, d, and s quarks, also called strange quark matter (SQM), posits that it represents the most energetically favorable state of matter. However, some studies [4, 5] have explored the flavor-dependent effects of quark gas on the QCD vacuum, suggesting that

$ u, d $ quark matter ($ u{\rm d}\mathrm{QM} $ ) is typically more stable than SQM. Notably, at sufficiently high baryon numbers,$ u{\rm d}\mathrm{QM} $ can surpass the stability of ordinary nuclei and extend beyond the periodic table. This finding has led to an increase in recent experimental pursuits [6−8] and phenomenological research [9−14].Along these lines, the MIT bag model [15] has been widely employed by several authors to describe massive NSs, i.e., NSs with a quark matter core, which have been detected in the past decade [16−19]. A modified version of this model, incorporating vector interactions and drawing features from quantum hadrodynamics (QHD) [20], has also been proposed and applied to SQM and QSs [21−24]. Building on these developments, Zhang et al. [25] introduced an EoS for QM that incorporates perturbative quantum chromodynamics (QCD) (pQCD) corrections and color superconductivity. This model has the notable advantage of producing massive QSs with larger radii consistent with recent astrophysical constraints. An additional feature is that, through a single parameter, the EoS can be rescaled into a dimensionless form, thereby reducing the number of free parameters and characterizing the relative strength of strong interaction effects [26−28].

However, in the presence of enormous densities and pressures in the interiors of such stars, one can expect that the pressure could be anisotropic, with the radial pressure differing from that in the azimuthal directions. In addition to these nuclear interactions [29], viscosity effects [30], pion condensation [31], and some kinds of phase transitions [32] may contribute to the presence of pressure anisotropy. Considering local anisotropy, QSs or NSs have been studied to extract information regarding their internal structure and nuclear physics (see, e.g., [33−44]). These investigations suggest that pressure anisotropy has a significant influence on the mass-radius relationship and the internal properties of stars, including the maximum surface redshift and maximum compactness. Note that the presence of anisotropy influences the stability of the configuration by supporting outwardly increasing energy density within the star core [45].

The above discussion suggests that investigations of anisotropic systems are typically conducted within the framework of Einstein's theory of gravity. Here, we study the stability of anisotropic QSs in gravity's rainbow. Gravity's rainbow [46] has been treated as an extension of the principles of doubly special relativity (DSR) [47] to curved spacetimes. This theory suggests a modification of the spacetime metric by introducing energy-dependent rainbow functions,

$ \Xi(x) $ and$ \Sigma(x) $ , which are characterized by the dimensionless ratio of the total energy of the probe particle E to the Planck energy$ E_p $ . This approach helps alter the relativistic dispersion relations. It allows for a deeper understanding of the relation between quantum mechanics and general relativity at high energy scales, particularly near the Planck scale [48, 49]. By incorporating energy-dependent effects into curved spacetimes, gravity's rainbow attempts to address some of the conceptual issues, such as black hole solutions and their properties [50−55], gravastars, and wormhole solutions [56, 57]. Other intriguing findings in this context are the studies on dark star [58] and NSs [59], which also analyze their stability-related issues.In summary, this study thoroughly investigates the possible existence of QSs with pressure anisotropy, emphasizing the interaction between strongly interacting QM and gravity's rainbow, where strongly interacting QM is considered. Focusing on understanding how these concepts affect the stability and detectability of QSs, and building upon recent theoretical works, we aim to gain a collective understanding of their fundamental properties. Inside these stars, the EoS strongly influences maximum mass and drives their internal structure, and it is susceptible to the strong interactions of QM. Conversely, gravity's rainbow alters the gravitational field at high energies, leading to modifications in compactness and, therefore, in the observational properties of the QSs. The theory of gravity and high matter interactions is varied in an attempt to study their combined effects on mass-radius relations, pulsar emissions, and gravitational wave signatures. Furthermore, it contributes to the knowledge of these constructs in broad astrophysics. This helps us even if we do not know the correct model yet, as it has some ideas for testing quantum gravity models in extreme astrophysical environments. In this study, we investigate the properties of QSs with modified parameters and anisotropic pressures within gravity's rainbow, focusing on their internal structure and stability in response to perturbations. Although the study by Zhang and Mann [25] provides a unified EoS for isotropic interacting QM and discusses the corresponding QS solutions within general relativity, our study presents an important extension in two directions: First, we consider pressure anisotropy in the stellar matter configuration, which is physically motivated in ultra-dense regimes owing to strong interaction effects, viscosity, or phase transitions; second, we introduce the gravity's rainbow formalism by modifying spacetime geometry via energy-dependent rainbow functions that can capture possible Lorentz-violating effects at high energies. With this combined framework, we investigate how anisotropic pressures and quantum gravity-inspired corrections jointly influence the mass-radius relation, compactness, and stability criteria of QSs, extending the description beyond what conventional isotropic models can achieve.

The remainder of this paper is structured in the following manner. In Sec. II, we provide a detailed description of the perturbative QCD-motivated EoS, and the derivation of the modified Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff (TOV) equations is also included. In Sec. III, we present the results of the numerical computation, illustrating the influence of the model parameters on the mass-radius relationships. Sec. IV comprehensively examines the static stability criterion, adiabatic index, and sound velocity. Finally, we discuss the results in Sec. V.

-

Current astronomical observations suggest that massive pulsars may have a core composed of QM rather than dense nuclear matter. Consequently, studying the internal properties of matter subjected to extreme conditions of density and temperature is an attractive area of research, along with identifying the associated EOS. This study uses the pQCD correction and color superconductivity to characterize the QM EoS, as outlined in Ref. [25]. The EoS can be rescaled into a dimensionless form, allowing it to depend on a single parameter. The rescaled procedure notably reduces the degrees of freedom, thereby enabling the relative size of strong interaction effects to be more accurately assessed. Thus, the EoS can be formulated as [25, 26]

$ P=\ \frac{1}{3}(\rho-4B_{{\rm{eff}}}) + \frac{4\lambda^2}{9\pi^2}\left[ -1+ {\rm sgn}(\lambda) \sqrt{1+3\pi^2 \frac{(\rho-B_{{\rm{eff}}})}{\lambda^2}} \right], $

(1) where ρ refers to the energy density associated with the homogeneously distributed QM, and P denotes the pressure variation along the radial direction. Here,

$ B_{{\rm{eff}}} $ is the effective bag constant, representing the non-perturbative contribution from the QCD vacuum; it acts as a confining pressure that stabilizes QM and, in general, may be flavor-dependent [25]. An additional significant quantity is$ {\rm sgn}(\lambda) $ , denoting the sign of λ,$ \lambda=\frac{\xi_{2a} \Delta^2-\xi_{2b} m_s^2}{\sqrt{\xi_4 a_4}}, $

(2) where

$ m_s $ denotes the mass of the strange quark, and Δ represents the gap parameter. Color superconductivity is a phase of cold, dense QM in which quarks form Cooper-like pairs owing to attractive strong interactions, analogous to electron pairing in conventional superconductors. This pairing modifies the EoS, enhancing the stiffness of QM and significantly influencing the macroscopic structure of QSs [60]. Moreover, the quartic coefficient$ a_4 $ can vary within the range$ a_4 \in (0,1) $ owing to pQCD contributions, whereas$ a_4 =1 $ denotes the case of noninteracting quarks. In this case,$ {\rm sgn}(\lambda) $ denotes the sign of λ with a positive value when$ \Delta^2/m_s^2>\xi_{2b}/\xi_{2a} $ . The constant coefficients in λ are$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} (\xi_4,\xi_{2a}, \xi_{2b}) =\\ \left\{ \begin{array} {ll} \Bigg(\Bigg( \left(\dfrac{1}{3}\right)^{\frac{4}{3}}+ \left(\dfrac{2}{3}\right)^{\frac{4}{3}}\Bigg)^{-3},1,0\Bigg), & \rm{2SC phase},\\ (3,1,3/4), & \rm{2SC+s phase},\\ (3,3,3/4),& \rm{CFL phase}. \end{array} \right. \end{array} $

In the present analysis, we restrict our attention to the positive λ space, which is favored by astrophysical models and observational findings [25, 61]. In this scenario, to eliminate the effective bag constant

$ B_{{\rm{eff}}} $ , we apply a dimensionless rescaling as proposed in [25],$ \bar{\lambda}=\frac{\lambda^2}{4B_{{\rm{eff}}}}= \frac{(\xi_{2a} \Delta^2-\xi_{2b} m_s^2)^2}{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}\xi_4 a_4}, $

(3) and

$ \bar{\rho} =\frac{\rho}{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}, \; \; \bar{P} =\frac{P}{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}, $

(4) thus introducing Eqs. (3) and (4) in Eq. (1), we have the following dimensionless form:

$ \bar{P} =\ \frac{1}{3}(\bar{\rho}-1) + \frac{4\bar{\lambda}}{9\pi^2} \left[-1+ \sqrt{1+ \frac{3\pi^2}{\bar{\lambda}} \left(\bar{\rho}-\frac{1}{4}\right)}\right] . $

(5) When examining the scenario where

$ \bar{\lambda} \to 0 $ , we can obtain the rescaled conventional noninteracting QM EoS represented by$ \bar{P}=\dfrac{1}{3}(\bar{\rho}-1) $ . In contrast, for extremely large positive values of$ \bar{\lambda} $ , the above expression has the following form:$ \bar{P}\vert_{\bar{\lambda}\to \infty}=\bar{\rho}-\frac{1}{2}. $

(6) or, equivalently,

$ P={\rho}-2B_{{\rm{eff}}} $ , using Eq. (4). According to Refs. [25, 26], positive increasing values of$ \bar{\lambda} $ result in a stiffer EoS, whereas$ \bar{\lambda} =0 $ represents noninteracting QM. The regularized$ 4D $ Einstein Gauss-Bonnet theory of gravity was also examined; for further information, see Refs. [28, 62]. -

Current astronomical observations suggest that massive pulsars may have a core composed of QM rather than dense nuclear matter. Consequently, studying the internal properties of matter subjected to extreme conditions of density and temperature is an attractive area of research, along with identifying the associated EOS. This study uses the pQCD correction and color superconductivity to characterize the QM EoS, as outlined in Ref. [25]. The EoS can be rescaled into a dimensionless form, allowing it to depend on a single parameter. The rescaled procedure notably reduces the degrees of freedom, thereby enabling the relative size of strong interaction effects to be more accurately assessed. Thus, the EoS can be formulated as [25, 26]

$ P=\ \frac{1}{3}(\rho-4B_{{\rm{eff}}}) + \frac{4\lambda^2}{9\pi^2}\left[ -1+ {\rm sgn}(\lambda) \sqrt{1+3\pi^2 \frac{(\rho-B_{{\rm{eff}}})}{\lambda^2}} \right], $

(1) where ρ refers to the energy density associated with the homogeneously distributed QM, and P denotes the pressure variation along the radial direction. Here,

$ B_{{\rm{eff}}} $ is the effective bag constant, representing the non-perturbative contribution from the QCD vacuum; it acts as a confining pressure that stabilizes QM and, in general, may be flavor-dependent [25]. An additional significant quantity is$ {\rm sgn}(\lambda) $ , denoting the sign of λ,$ \lambda=\frac{\xi_{2a} \Delta^2-\xi_{2b} m_s^2}{\sqrt{\xi_4 a_4}}, $

(2) where

$ m_s $ denotes the mass of the strange quark, and Δ represents the gap parameter. Color superconductivity is a phase of cold, dense QM in which quarks form Cooper-like pairs owing to attractive strong interactions, analogous to electron pairing in conventional superconductors. This pairing modifies the EoS, enhancing the stiffness of QM and significantly influencing the macroscopic structure of QSs [60]. Moreover, the quartic coefficient$ a_4 $ can vary within the range$ a_4 \in (0,1) $ owing to pQCD contributions, whereas$ a_4 =1 $ denotes the case of noninteracting quarks. In this case,$ {\rm sgn}(\lambda) $ denotes the sign of λ with a positive value when$ \Delta^2/m_s^2>\xi_{2b}/\xi_{2a} $ . The constant coefficients in λ are$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} (\xi_4,\xi_{2a}, \xi_{2b}) =\\ \left\{ \begin{array} {ll} \Bigg(\Bigg( \left(\dfrac{1}{3}\right)^{\frac{4}{3}}+ \left(\dfrac{2}{3}\right)^{\frac{4}{3}}\Bigg)^{-3},1,0\Bigg), & \rm{2SC phase},\\ (3,1,3/4), & \rm{2SC+s phase},\\ (3,3,3/4),& \rm{CFL phase}. \end{array} \right. \end{array} $

In the present analysis, we restrict our attention to the positive λ space, which is favored by astrophysical models and observational findings [25, 61]. In this scenario, to eliminate the effective bag constant

$ B_{{\rm{eff}}} $ , we apply a dimensionless rescaling as proposed in [25],$ \bar{\lambda}=\frac{\lambda^2}{4B_{{\rm{eff}}}}= \frac{(\xi_{2a} \Delta^2-\xi_{2b} m_s^2)^2}{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}\xi_4 a_4}, $

(3) and

$ \bar{\rho} =\frac{\rho}{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}, \; \; \bar{P} =\frac{P}{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}, $

(4) thus introducing Eqs. (3) and (4) in Eq. (1), we have the following dimensionless form:

$ \bar{P} =\ \frac{1}{3}(\bar{\rho}-1) + \frac{4\bar{\lambda}}{9\pi^2} \left[-1+ \sqrt{1+ \frac{3\pi^2}{\bar{\lambda}} \left(\bar{\rho}-\frac{1}{4}\right)}\right] . $

(5) When examining the scenario where

$ \bar{\lambda} \to 0 $ , we can obtain the rescaled conventional noninteracting QM EoS represented by$ \bar{P}=\dfrac{1}{3}(\bar{\rho}-1) $ . In contrast, for extremely large positive values of$ \bar{\lambda} $ , the above expression has the following form:$ \bar{P}\vert_{\bar{\lambda}\to \infty}=\bar{\rho}-\frac{1}{2}. $

(6) or, equivalently,

$ P={\rho}-2B_{{\rm{eff}}} $ , using Eq. (4). According to Refs. [25, 26], positive increasing values of$ \bar{\lambda} $ result in a stiffer EoS, whereas$ \bar{\lambda} =0 $ represents noninteracting QM. The regularized$ 4D $ Einstein Gauss-Bonnet theory of gravity was also examined; for further information, see Refs. [28, 62]. -

Current astronomical observations suggest that massive pulsars may have a core composed of QM rather than dense nuclear matter. Consequently, studying the internal properties of matter subjected to extreme conditions of density and temperature is an attractive area of research, along with identifying the associated EOS. This study uses the pQCD correction and color superconductivity to characterize the QM EoS, as outlined in Ref. [25]. The EoS can be rescaled into a dimensionless form, allowing it to depend on a single parameter. The rescaled procedure notably reduces the degrees of freedom, thereby enabling the relative size of strong interaction effects to be more accurately assessed. Thus, the EoS can be formulated as [25, 26]

$ P=\ \frac{1}{3}(\rho-4B_{{\rm{eff}}}) + \frac{4\lambda^2}{9\pi^2}\left[ -1+ {\rm sgn}(\lambda) \sqrt{1+3\pi^2 \frac{(\rho-B_{{\rm{eff}}})}{\lambda^2}} \right], $

(1) where ρ refers to the energy density associated with the homogeneously distributed QM, and P denotes the pressure variation along the radial direction. Here,

$ B_{{\rm{eff}}} $ is the effective bag constant, representing the non-perturbative contribution from the QCD vacuum; it acts as a confining pressure that stabilizes QM and, in general, may be flavor-dependent [25]. An additional significant quantity is$ {\rm sgn}(\lambda) $ , denoting the sign of λ,$ \lambda=\frac{\xi_{2a} \Delta^2-\xi_{2b} m_s^2}{\sqrt{\xi_4 a_4}}, $

(2) where

$ m_s $ denotes the mass of the strange quark, and Δ represents the gap parameter. Color superconductivity is a phase of cold, dense QM in which quarks form Cooper-like pairs owing to attractive strong interactions, analogous to electron pairing in conventional superconductors. This pairing modifies the EoS, enhancing the stiffness of QM and significantly influencing the macroscopic structure of QSs [60]. Moreover, the quartic coefficient$ a_4 $ can vary within the range$ a_4 \in (0,1) $ owing to pQCD contributions, whereas$ a_4 =1 $ denotes the case of noninteracting quarks. In this case,$ {\rm sgn}(\lambda) $ denotes the sign of λ with a positive value when$ \Delta^2/m_s^2>\xi_{2b}/\xi_{2a} $ . The constant coefficients in λ are$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} (\xi_4,\xi_{2a}, \xi_{2b}) =\\ \left\{ \begin{array} {ll} \Bigg(\Bigg( \left(\dfrac{1}{3}\right)^{\frac{4}{3}}+ \left(\dfrac{2}{3}\right)^{\frac{4}{3}}\Bigg)^{-3},1,0\Bigg), & \rm{2SC phase},\\ (3,1,3/4), & \rm{2SC+s phase},\\ (3,3,3/4),& \rm{CFL phase}. \end{array} \right. \end{array} $

In the present analysis, we restrict our attention to the positive λ space, which is favored by astrophysical models and observational findings [25, 61]. In this scenario, to eliminate the effective bag constant

$ B_{{\rm{eff}}} $ , we apply a dimensionless rescaling as proposed in [25],$ \bar{\lambda}=\frac{\lambda^2}{4B_{{\rm{eff}}}}= \frac{(\xi_{2a} \Delta^2-\xi_{2b} m_s^2)^2}{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}\xi_4 a_4}, $

(3) and

$ \bar{\rho} =\frac{\rho}{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}, \; \; \bar{P} =\frac{P}{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}, $

(4) thus introducing Eqs. (3) and (4) in Eq. (1), we have the following dimensionless form:

$ \bar{P} =\ \frac{1}{3}(\bar{\rho}-1) + \frac{4\bar{\lambda}}{9\pi^2} \left[-1+ \sqrt{1+ \frac{3\pi^2}{\bar{\lambda}} \left(\bar{\rho}-\frac{1}{4}\right)}\right] . $

(5) When examining the scenario where

$ \bar{\lambda} \to 0 $ , we can obtain the rescaled conventional noninteracting QM EoS represented by$ \bar{P}=\dfrac{1}{3}(\bar{\rho}-1) $ . In contrast, for extremely large positive values of$ \bar{\lambda} $ , the above expression has the following form:$ \bar{P}\vert_{\bar{\lambda}\to \infty}=\bar{\rho}-\frac{1}{2}. $

(6) or, equivalently,

$ P={\rho}-2B_{{\rm{eff}}} $ , using Eq. (4). According to Refs. [25, 26], positive increasing values of$ \bar{\lambda} $ result in a stiffer EoS, whereas$ \bar{\lambda} =0 $ represents noninteracting QM. The regularized$ 4D $ Einstein Gauss-Bonnet theory of gravity was also examined; for further information, see Refs. [28, 62]. -

Current astronomical observations suggest that massive pulsars may have a core composed of quark matter rather than dense nuclear matter. As a result, studying the internal properties of matter subjected to extreme conditions of density and temperature is an attractive area of research, along with identifying the associated EOS. This article will use the perturbative QCD (pQCD) correction and color superconductivity to characterise the QM EoS, as outlined in Ref. [25]. The EoS can be rescaled into a dimensionless form, allowing it to depend on a single parameter. The rescaled procedure notably reduces the degrees of freedom, thereby allowing for the relative size of strong interaction effects to be more accurately assessed. Taking this into account, the EoS can be formulated as [25, 26]:

$ P=\ \frac{1}{3}(\rho-4B_{{\rm{eff}}}) + \frac{4\lambda^2}{9\pi^2}\left[ -1+ {\rm sgn}(\lambda) \sqrt{1+3\pi^2 \frac{(\rho-B_{{\rm{eff}}})}{\lambda^2}} \right], $

(1) where ρ refers to the energy density associated with the homogeneously distributed QM, and P denotes the pressure variation along the radial direction. Here,

$ B_{{\rm{eff}}} $ is the effective bag constant, representing the non-perturbative contribution from the QCD vacuum; it acts as a confining pressure that stabilizes quark matter and, in general, may be flavor-dependent [25]. An additional significant quantity is the$ {\rm sgn}(\lambda) $ , denoting the sign of λ,$ \lambda=\frac{\xi_{2a} \Delta^2-\xi_{2b} m_s^2}{\sqrt{\xi_4 a_4}}, $

(2) where

$ m_s $ denotes the mass of the strange quark and Δ represents the gap parameter. Color superconductivity is a phase of cold, dense quark matter in which quarks form Cooper-like pairs due to attractive strong interactions, analogous to electron pairing in conventional superconductors. This pairing modifies the equation of state, enhancing the stiffness of quark matter and significantly influencing the macroscopic structure of quark stars [61]. Moreover, the quartic coefficient$ a_4 $ can change within the range$ a_4 \in (0,1) $ due to pQCD contributions, while$ a_4 =1 $ denotes the case of noninteracting quarks. In this case,$ {\rm sgn}(\lambda) $ denotes the sign of λ with a positive value when$ \Delta^2/m_s^2>\xi_{2b}/\xi_{2a} $ . The constant coefficients in λ are$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} (\xi_4,\xi_{2a}, \xi_{2b}) =\\ \left\{ \begin{array} {ll} \Bigg(\Bigg( \left(\dfrac{1}{3}\right)^{\frac{4}{3}}+ \left(\dfrac{2}{3}\right)^{\frac{4}{3}}\Bigg)^{-3},1,0\Bigg) & \rm{2SC phase}\\ (3,1,3/4) & \rm{2SC+s phase}\\ (3,3,3/4)& \rm{CFL phase} \end{array} \right. \end{array} $

In the present analysis, we restrict our attention to the positive λ space, which is favored by astrophysical models and observational findings [25, 62]. In this scenario, to eliminate the effective bag constant

$ B_{{\rm{eff}}} $ , we apply a dimensionless rescaling as proposed in [25],$ \bar{\lambda}=\frac{\lambda^2}{4B_{{\rm{eff}}}}= \frac{(\xi_{2a} \Delta^2-\xi_{2b} m_s^2)^2}{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}\xi_4 a_4}, $

(3) and

$ \bar{\rho} =\frac{\rho}{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}, \; \; \bar{P} =\frac{P}{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}, $

(4) thus introducing (3) and (4) in Eq. (1), we have the following dimensionless form:

$ \bar{P} =\ \frac{1}{3}(\bar{\rho}-1) + \frac{4\bar{\lambda}}{9\pi^2} \left[-1+ \sqrt{1+ \frac{3\pi^2}{\bar{\lambda}} \left(\bar{\rho}-\frac{1}{4}\right)}\right] . $

(5) When examining the scenario where

$ \bar{\lambda} \to 0 $ , we can obtain the rescaled conventional noninteracting QM EoS represented by$ \bar{P}=\dfrac{1}{3}(\bar{\rho}-1) $ . In contrast, for extremely large positive values of$ \bar{\lambda} $ , the above expression has the following form$ \bar{P}\vert_{\bar{\lambda}\to \infty}=\bar{\rho}-\frac{1}{2}. $

(6) or, equivalently,

$ P={\rho}-2B_{{\rm{eff}}} $ , using Eq. (4). According to Ref. [25, 26], it was noted that for positive increasing values of$ \bar{\lambda} $ result in stiffer EoS, while$ \bar{\lambda} =0 $ represents noninteracting QM. The regularized$ 4D $ Einstein Gauss-Bonnet theory of gravity was also examined; for further information, see Ref. [28, 29]. -

In this section, we derive the equations of hydrostatic equilibrium in rainbow gravity, assuming a static,

$ 4D $ spherically symmetric metric that is substituted with a rainbow metric represented as follows: [46],$ {\rm d}s^{2} = -\frac{{\rm e}^{2\Phi(r)}}{\Xi^{2}(x)}\, {\rm d}t^{2} + \frac{{\rm e}^{2\lambda(r)}}{\Sigma^{2}(x)}\, {\rm d}r^{2} + \frac{r^{2}}{\Sigma^{2}(x)}\, {\rm d}\Omega^{2}, $

(7) where

$ \Phi(r) $ and$ \lambda(r) $ are radial functions to be determined, and$ {\rm d}\Omega^{2} = {\rm d}\theta^{2} + \sin^{2}\theta\, {\rm d}\phi^{2} $ denotes the metric on the unit 2-sphere. The rainbow functions$ \Xi(x) $ and$ \Sigma(x) $ depend only on the dimensionless ratio$ x = E/E_{p} $ , with E denoting the total energy of the particle and$ E_{p} $ the Planck energy, defined as$ E_{p} = \sqrt{\hbar c^{5}/G} $ . They are independent of the spacetime coordinates$ (t,r,\theta,\phi) $ .Motivated by [63, 64], we explore the possible existence of a QS with anisotropic pressure in the context of rainbow gravity. Therefore, we define the fluid in the matter sector as locally anisotropic and express the energy-momentum tensor as follows:

$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} T_{\mu\nu}=(\rho+P_{\perp})u_\mu u_\nu+ P_{\perp} g_{\mu\nu}+\left(P-P_{\perp}\right)\chi_{\mu}\chi_{\nu}, \end{array} $

(8) where

$ u^\mu $ denotes the (timelike) 4-velocity of the fluid, and$ \chi_{\mu} $ represents a unit radial vector that fulfills$ \chi_{\mu} \chi^{\mu} = 1 $ . Indeed, P denotes the radial pressure, and$ P_{\perp} $ represents the transverse pressure. Furthermore, we express the generalized EoS for the tangential pressure as follows [63]:$ \begin{aligned}[b] P_{\perp}=\;& P_c +\dfrac{1}{3}\left(\rho-4B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp}\right) \\&+ \frac{4\lambda_{\perp}^2}{9\pi^2}\left[ -1+\sqrt{1+3\pi^2 \frac{(\rho-B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp})}{\lambda_{\perp}^2}} \right] \\ & -\dfrac{1}{3}\left(\rho_c-4B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp}\right) \\&- \frac{4\lambda_{\perp}^2}{9\pi^2}\left[ -1+\sqrt{1+3\pi^2 \frac{(\rho_c-B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp})}{\lambda_{\perp}^2}} \right], \end{aligned} $

(9) where

$ P_c $ and$ \rho_c $ in Eq. (9) represent the radial pressure (Eq. (5)) and energy density, respectively, at the center of the star. At the core of the star, specifically at$ r=0 $ , it is observed that the radial and tangential pressures are equivalent when the conditions$ B_{\rm{eff}} = B_{\rm{eff}}, \perp $ and$ \lambda=\lambda_{\perp} $ are satisfied. This condition indicates that the fluid attains isotropy at the center of the star. Additionally, the parameters$ B_{\rm{eff}}, \perp $ and$ \lambda_{\perp} $ contribute to the tangential pressure and are within the same value ranges as$ B_{{\rm{eff}}} $ and λ, respectively. Note that, in this setup, the parameters for the radial and tangential directions, written as λ and$ \lambda_\perp $ , respectively, are allowed to differ. This does not imply that the underlying microscopic physics changes with direction; rather, it provides a way to capture how strong interactions, possible phase transitions, or collective stresses might manifest as anisotropic behavior. At the stellar center, we impose$ \lambda=\lambda_\perp $ , thereby restoring isotropy, whereas controlled deviations arise only away from the center. In this sense, the construction is analogous in spirit to other anisotropy models considered in literature. Still, here it is cast in a more compact and microphysically motivated form, naturally embedded within the gravity’s rainbow framework. In contrast to the commonly used Bowers–Liang [65] or quasi-local models [45], which introduce anisotropy through externally prescribed stress profiles$ \Delta(r) $ , our formulation emerges as a direct extension of the interacting QM EoS. This approach naturally permits distinct couplings for radial and tangential pressures, while ensuring isotropy at the center, thereby providing a consistent way to incorporate strong-interaction corrections. Further, we remove the$ B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp} $ parameter by applying dimensionless rescaling as follows:$ \bar{P}_\perp =\frac{P_\perp}{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}, \; \bar{\lambda}_{\perp}=\frac{\lambda^2_{\perp}}{4B_{{\rm{eff}}}} \; \text{and}\; \bar{B} = \frac{B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp}}{B_{{\rm{eff}}}}, $

(10) and ultimately, we obtain the pressure in the transverse direction in the following dimensionless form:

$ \begin{aligned}[b] \bar{P}_{\perp} =\;& \bar{P}_{c} + \frac{1}{3}(\bar{\rho} - \bar{B}) \\&+ \frac{4\bar{\lambda}_{\perp}}{9\pi^2} \left[-1+ \sqrt{1+ \frac{3\pi^2}{\bar{\lambda}_{\perp}} \left(\bar{\rho}-\frac{\bar{B}}{4}\right)}\right] \\ & -\frac{1}{3}(\bar{\rho}_{c} - \bar{B}) - \frac{4\bar{\lambda}_{\perp}}{9\pi^2} \left[-1+ \sqrt{1+ \frac{3\pi^2}{\bar{\lambda}_{\perp}} \left(\bar{\rho}_{c}-\frac{\bar{B}}{4}\right)}\right]. \end{aligned} $

(11) Here, we rescale the mass and radius into a dimensionless form,

$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} \bar{m} = m \sqrt{{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}} \; ~{\rm and}~\; \bar{r} = r \sqrt{{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}}\; . \end{array} $

(12) Here, the parameters are rescaled with respect to the effective bag constant, which sets the natural energy scale of the QM system. This rescaling reduces the number of free parameters and allows the EoS to be cast in a compact dimensionless form. It also ensures that the formulation connects smoothly to the standard GR limit in the absence of rainbow corrections, while retaining the effects of strong interactions in a controlled manner. Finally, using Eqs. (7) and (8), the modified TOV equations are [46, 59] (we work with natural units

$ G = \hslash= c = 1 $ )$ M_{\rm{eff}}(r, x)= \int^{r}_{0} \frac{4 \pi r^2 \rho(r)}{\Sigma^{2}(x)} {\rm d}r \equiv \frac{m(r)}{\Sigma^{2}(x)}, $

(13) $ P' = -(\rho+P_{r})\Phi'+ \frac{2}{r}\left(P_{\bot}-P\right), $

(14) $ \Phi'(r)=\frac{M_{\rm{eff}}(r, x) \Sigma^{2}(x)+4\pi r^3 P}{r\left(r-2M_{\rm{eff}}(r, x) \right)\Sigma^{2}(x)}, $

(15) where the prime denotes the derivative with respect to the radial coordinate r. We can also transform it into a dimensionless form by substituting the non-barred symbols with their corresponding barred counterparts. Note that the normal relation

$ (M, R) $ can be recovered by introducing$ (M, R) $ =$ (\bar{M}/ \sqrt{{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}}, \bar{R}/ \sqrt{{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}}) $ , and we present$ M-R $ relations in normalized form. -

In this section, we derive the equations of hydrostatic equilibrium in rainbow gravity, assuming a static,

$ 4D $ spherically symmetric metric that is substituted with a rainbow metric represented as follows: [46],$ {\rm d}s^{2} = -\frac{{\rm e}^{2\Phi(r)}}{\Xi^{2}(x)}\, {\rm d}t^{2} + \frac{{\rm e}^{2\lambda(r)}}{\Sigma^{2}(x)}\, {\rm d}r^{2} + \frac{r^{2}}{\Sigma^{2}(x)}\, {\rm d}\Omega^{2}, $

(7) where

$ \Phi(r) $ and$ \lambda(r) $ are radial functions to be determined, and$ {\rm d}\Omega^{2} = {\rm d}\theta^{2} + \sin^{2}\theta\, {\rm d}\phi^{2} $ denotes the metric on the unit 2-sphere. The rainbow functions$ \Xi(x) $ and$ \Sigma(x) $ depend only on the dimensionless ratio$ x = E/E_{p} $ , with E denoting the total energy of the particle and$ E_{p} $ the Planck energy, defined as$ E_{p} = \sqrt{\hbar c^{5}/G} $ . They are independent of the spacetime coordinates$ (t,r,\theta,\phi) $ .Motivated by [63, 64], we explore the possible existence of a QS with anisotropic pressure in the context of rainbow gravity. Therefore, we define the fluid in the matter sector as locally anisotropic and express the energy-momentum tensor as follows:

$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} T_{\mu\nu}=(\rho+P_{\perp})u_\mu u_\nu+ P_{\perp} g_{\mu\nu}+\left(P-P_{\perp}\right)\chi_{\mu}\chi_{\nu}, \end{array} $

(8) where

$ u^\mu $ denotes the (timelike) 4-velocity of the fluid, and$ \chi_{\mu} $ represents a unit radial vector that fulfills$ \chi_{\mu} \chi^{\mu} = 1 $ . Indeed, P denotes the radial pressure, and$ P_{\perp} $ represents the transverse pressure. Furthermore, we express the generalized EoS for the tangential pressure as follows [63]:$ \begin{aligned}[b] P_{\perp}=\;& P_c +\dfrac{1}{3}\left(\rho-4B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp}\right) \\&+ \frac{4\lambda_{\perp}^2}{9\pi^2}\left[ -1+\sqrt{1+3\pi^2 \frac{(\rho-B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp})}{\lambda_{\perp}^2}} \right] \\ & -\dfrac{1}{3}\left(\rho_c-4B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp}\right) \\&- \frac{4\lambda_{\perp}^2}{9\pi^2}\left[ -1+\sqrt{1+3\pi^2 \frac{(\rho_c-B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp})}{\lambda_{\perp}^2}} \right], \end{aligned} $

(9) where

$ P_c $ and$ \rho_c $ in Eq. (9) represent the radial pressure (Eq. (5)) and energy density, respectively, at the center of the star. At the core of the star, specifically at$ r=0 $ , it is observed that the radial and tangential pressures are equivalent when the conditions$ B_{\rm{eff}} = B_{\rm{eff}}, \perp $ and$ \lambda=\lambda_{\perp} $ are satisfied. This condition indicates that the fluid attains isotropy at the center of the star. Additionally, the parameters$ B_{\rm{eff}}, \perp $ and$ \lambda_{\perp} $ contribute to the tangential pressure and are within the same value ranges as$ B_{{\rm{eff}}} $ and λ, respectively. Note that, in this setup, the parameters for the radial and tangential directions, written as λ and$ \lambda_\perp $ , respectively, are allowed to differ. This does not imply that the underlying microscopic physics changes with direction; rather, it provides a way to capture how strong interactions, possible phase transitions, or collective stresses might manifest as anisotropic behavior. At the stellar center, we impose$ \lambda=\lambda_\perp $ , thereby restoring isotropy, whereas controlled deviations arise only away from the center. In this sense, the construction is analogous in spirit to other anisotropy models considered in literature. Still, here it is cast in a more compact and microphysically motivated form, naturally embedded within the gravity’s rainbow framework. In contrast to the commonly used Bowers–Liang [65] or quasi-local models [45], which introduce anisotropy through externally prescribed stress profiles$ \Delta(r) $ , our formulation emerges as a direct extension of the interacting QM EoS. This approach naturally permits distinct couplings for radial and tangential pressures, while ensuring isotropy at the center, thereby providing a consistent way to incorporate strong-interaction corrections. Further, we remove the$ B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp} $ parameter by applying dimensionless rescaling as follows:$ \bar{P}_\perp =\frac{P_\perp}{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}, \; \bar{\lambda}_{\perp}=\frac{\lambda^2_{\perp}}{4B_{{\rm{eff}}}} \; \text{and}\; \bar{B} = \frac{B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp}}{B_{{\rm{eff}}}}, $

(10) and ultimately, we obtain the pressure in the transverse direction in the following dimensionless form:

$ \begin{aligned}[b] \bar{P}_{\perp} =\;& \bar{P}_{c} + \frac{1}{3}(\bar{\rho} - \bar{B}) \\&+ \frac{4\bar{\lambda}_{\perp}}{9\pi^2} \left[-1+ \sqrt{1+ \frac{3\pi^2}{\bar{\lambda}_{\perp}} \left(\bar{\rho}-\frac{\bar{B}}{4}\right)}\right] \\ & -\frac{1}{3}(\bar{\rho}_{c} - \bar{B}) - \frac{4\bar{\lambda}_{\perp}}{9\pi^2} \left[-1+ \sqrt{1+ \frac{3\pi^2}{\bar{\lambda}_{\perp}} \left(\bar{\rho}_{c}-\frac{\bar{B}}{4}\right)}\right]. \end{aligned} $

(11) Here, we rescale the mass and radius into a dimensionless form,

$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} \bar{m} = m \sqrt{{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}} \; ~{\rm and}~\; \bar{r} = r \sqrt{{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}}\; . \end{array} $

(12) Here, the parameters are rescaled with respect to the effective bag constant, which sets the natural energy scale of the QM system. This rescaling reduces the number of free parameters and allows the EoS to be cast in a compact dimensionless form. It also ensures that the formulation connects smoothly to the standard GR limit in the absence of rainbow corrections, while retaining the effects of strong interactions in a controlled manner. Finally, using Eqs. (7) and (8), the modified TOV equations are [46, 59] (we work with natural units

$ G = \hslash= c = 1 $ )$ M_{\rm{eff}}(r, x)= \int^{r}_{0} \frac{4 \pi r^2 \rho(r)}{\Sigma^{2}(x)} {\rm d}r \equiv \frac{m(r)}{\Sigma^{2}(x)}, $

(13) $ P' = -(\rho+P_{r})\Phi'+ \frac{2}{r}\left(P_{\bot}-P\right), $

(14) $ \Phi'(r)=\frac{M_{\rm{eff}}(r, x) \Sigma^{2}(x)+4\pi r^3 P}{r\left(r-2M_{\rm{eff}}(r, x) \right)\Sigma^{2}(x)}, $

(15) where the prime denotes the derivative with respect to the radial coordinate r. We can also transform it into a dimensionless form by substituting the non-barred symbols with their corresponding barred counterparts. Note that the normal relation

$ (M, R) $ can be recovered by introducing$ (M, R) $ =$ (\bar{M}/ \sqrt{{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}}, \bar{R}/ \sqrt{{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}}) $ , and we present$ M-R $ relations in normalized form. -

In this section, we derive the equations of hydrostatic equilibrium in rainbow gravity, assuming a static,

$ 4D $ spherically symmetric metric that is substituted with a rainbow metric represented as follows: [46],$ {\rm d}s^{2} = -\frac{{\rm e}^{2\Phi(r)}}{\Xi^{2}(x)}\, {\rm d}t^{2} + \frac{{\rm e}^{2\lambda(r)}}{\Sigma^{2}(x)}\, {\rm d}r^{2} + \frac{r^{2}}{\Sigma^{2}(x)}\, {\rm d}\Omega^{2}, $

(7) where

$ \Phi(r) $ and$ \lambda(r) $ are radial functions to be determined, and$ {\rm d}\Omega^{2} = {\rm d}\theta^{2} + \sin^{2}\theta\, {\rm d}\phi^{2} $ denotes the metric on the unit 2-sphere. The rainbow functions$ \Xi(x) $ and$ \Sigma(x) $ depend only on the dimensionless ratio$ x = E/E_{p} $ , with E denoting the total energy of the particle and$ E_{p} $ the Planck energy, defined as$ E_{p} = \sqrt{\hbar c^{5}/G} $ . They are independent of the spacetime coordinates$ (t,r,\theta,\phi) $ .Motivated by [63, 64], we explore the possible existence of a QS with anisotropic pressure in the context of rainbow gravity. Therefore, we define the fluid in the matter sector as locally anisotropic and express the energy-momentum tensor as follows:

$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} T_{\mu\nu}=(\rho+P_{\perp})u_\mu u_\nu+ P_{\perp} g_{\mu\nu}+\left(P-P_{\perp}\right)\chi_{\mu}\chi_{\nu}, \end{array} $

(8) where

$ u^\mu $ denotes the (timelike) 4-velocity of the fluid, and$ \chi_{\mu} $ represents a unit radial vector that fulfills$ \chi_{\mu} \chi^{\mu} = 1 $ . Indeed, P denotes the radial pressure, and$ P_{\perp} $ represents the transverse pressure. Furthermore, we express the generalized EoS for the tangential pressure as follows [63]:$ \begin{aligned}[b] P_{\perp}=\;& P_c +\dfrac{1}{3}\left(\rho-4B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp}\right) \\&+ \frac{4\lambda_{\perp}^2}{9\pi^2}\left[ -1+\sqrt{1+3\pi^2 \frac{(\rho-B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp})}{\lambda_{\perp}^2}} \right] \\ & -\dfrac{1}{3}\left(\rho_c-4B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp}\right) \\&- \frac{4\lambda_{\perp}^2}{9\pi^2}\left[ -1+\sqrt{1+3\pi^2 \frac{(\rho_c-B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp})}{\lambda_{\perp}^2}} \right], \end{aligned} $

(9) where

$ P_c $ and$ \rho_c $ in Eq. (9) represent the radial pressure (Eq. (5)) and energy density, respectively, at the center of the star. At the core of the star, specifically at$ r=0 $ , it is observed that the radial and tangential pressures are equivalent when the conditions$ B_{\rm{eff}} = B_{\rm{eff}}, \perp $ and$ \lambda=\lambda_{\perp} $ are satisfied. This condition indicates that the fluid attains isotropy at the center of the star. Additionally, the parameters$ B_{\rm{eff}}, \perp $ and$ \lambda_{\perp} $ contribute to the tangential pressure and are within the same value ranges as$ B_{{\rm{eff}}} $ and λ, respectively. Note that, in this setup, the parameters for the radial and tangential directions, written as λ and$ \lambda_\perp $ , respectively, are allowed to differ. This does not imply that the underlying microscopic physics changes with direction; rather, it provides a way to capture how strong interactions, possible phase transitions, or collective stresses might manifest as anisotropic behavior. At the stellar center, we impose$ \lambda=\lambda_\perp $ , thereby restoring isotropy, whereas controlled deviations arise only away from the center. In this sense, the construction is analogous in spirit to other anisotropy models considered in literature. Still, here it is cast in a more compact and microphysically motivated form, naturally embedded within the gravity’s rainbow framework. In contrast to the commonly used Bowers–Liang [65] or quasi-local models [45], which introduce anisotropy through externally prescribed stress profiles$ \Delta(r) $ , our formulation emerges as a direct extension of the interacting QM EoS. This approach naturally permits distinct couplings for radial and tangential pressures, while ensuring isotropy at the center, thereby providing a consistent way to incorporate strong-interaction corrections. Further, we remove the$ B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp} $ parameter by applying dimensionless rescaling as follows:$ \bar{P}_\perp =\frac{P_\perp}{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}, \; \bar{\lambda}_{\perp}=\frac{\lambda^2_{\perp}}{4B_{{\rm{eff}}}} \; \text{and}\; \bar{B} = \frac{B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp}}{B_{{\rm{eff}}}}, $

(10) and ultimately, we obtain the pressure in the transverse direction in the following dimensionless form:

$ \begin{aligned}[b] \bar{P}_{\perp} =\;& \bar{P}_{c} + \frac{1}{3}(\bar{\rho} - \bar{B}) \\&+ \frac{4\bar{\lambda}_{\perp}}{9\pi^2} \left[-1+ \sqrt{1+ \frac{3\pi^2}{\bar{\lambda}_{\perp}} \left(\bar{\rho}-\frac{\bar{B}}{4}\right)}\right] \\ & -\frac{1}{3}(\bar{\rho}_{c} - \bar{B}) - \frac{4\bar{\lambda}_{\perp}}{9\pi^2} \left[-1+ \sqrt{1+ \frac{3\pi^2}{\bar{\lambda}_{\perp}} \left(\bar{\rho}_{c}-\frac{\bar{B}}{4}\right)}\right]. \end{aligned} $

(11) Here, we rescale the mass and radius into a dimensionless form,

$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} \bar{m} = m \sqrt{{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}} \; ~{\rm and}~\; \bar{r} = r \sqrt{{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}}\; . \end{array} $

(12) Here, the parameters are rescaled with respect to the effective bag constant, which sets the natural energy scale of the QM system. This rescaling reduces the number of free parameters and allows the EoS to be cast in a compact dimensionless form. It also ensures that the formulation connects smoothly to the standard GR limit in the absence of rainbow corrections, while retaining the effects of strong interactions in a controlled manner. Finally, using Eqs. (7) and (8), the modified TOV equations are [46, 59] (we work with natural units

$ G = \hslash= c = 1 $ )$ M_{\rm{eff}}(r, x)= \int^{r}_{0} \frac{4 \pi r^2 \rho(r)}{\Sigma^{2}(x)} {\rm d}r \equiv \frac{m(r)}{\Sigma^{2}(x)}, $

(13) $ P' = -(\rho+P_{r})\Phi'+ \frac{2}{r}\left(P_{\bot}-P\right), $

(14) $ \Phi'(r)=\frac{M_{\rm{eff}}(r, x) \Sigma^{2}(x)+4\pi r^3 P}{r\left(r-2M_{\rm{eff}}(r, x) \right)\Sigma^{2}(x)}, $

(15) where the prime denotes the derivative with respect to the radial coordinate r. We can also transform it into a dimensionless form by substituting the non-barred symbols with their corresponding barred counterparts. Note that the normal relation

$ (M, R) $ can be recovered by introducing$ (M, R) $ =$ (\bar{M}/ \sqrt{{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}}, \bar{R}/ \sqrt{{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}}) $ , and we present$ M-R $ relations in normalized form. -

In this section, we proceed to derive the equations of hydrostatic equilibrium in rainbow gravity, assuming a static,

$ 4D $ spherically symmetric metric that is substituted with a rainbow metric represented as follows [47],$ ds^{2} = -\frac{e^{2\Phi(r)}}{\Xi^{2}(x)}\, dt^{2} + \frac{e^{2\lambda(r)}}{\Sigma^{2}(x)}\, dr^{2} + \frac{r^{2}}{\Sigma^{2}(x)}\, d\Omega^{2}, $

(7) where

$ \Phi(r) $ and$ \lambda(r) $ are radial functions to be determined, and$ d\Omega^{2} = d\theta^{2} + \sin^{2}\theta\, d\phi^{2} $ denotes the metric on the unit 2-sphere. The rainbow functions$ \Xi(x) $ and$ \Sigma(x) $ depend only on the dimensionless ratio$ x = E/E_{p} $ , with E denoting the total energy of the particle and$ E_{p} $ the Planck energy, defined as$ E_{p} = \sqrt{\hbar c^{5}/G} $ . They are independent of the spacetime coordinates$ (t,r,\theta,\phi) $ .Motivated by [63, 65], we explore the possible existence of a quark star with anisotropic pressure in the context of rainbow gravity. Therefore, we define the fluid in the matter sector as locally anisotropic and express the energy-momentum tensor as follows:

$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} T_{\mu\nu}=(\rho+P_{\perp})u_\mu u_\nu+ P_{\perp} g_{\mu\nu}+\left(P-P_{\perp}\right)\chi_{\mu}\chi_{\nu}, \end{array} $

(8) where

$ u^\mu $ denotes the (timelike) 4-velocity of the fluid and$ \chi_{\mu} $ represents a unit radial vector that fulfills$ \chi_{\mu} \chi^{\mu} = 1 $ . Indeed, P denotes the radial pressure, while$ P_{\perp} $ represents the transverse pressure. Furthermore, we write down the generalized EoS for the tangential pressure [63]$ \begin{aligned}[b] P_{\perp}=\;& P_c +\dfrac{1}{3}\left(\rho-4B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp}\right) \\&+ \frac{4\lambda_{\perp}^2}{9\pi^2}\left[ -1+\sqrt{1+3\pi^2 \frac{(\rho-B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp})}{\lambda_{\perp}^2}} \right] \\ & -\dfrac{1}{3}\left(\rho_c-4B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp}\right) \\&- \frac{4\lambda_{\perp}^2}{9\pi^2}\left[ -1+\sqrt{1+3\pi^2 \frac{(\rho_c-B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp})}{\lambda_{\perp}^2}} \right], \end{aligned} $

(9) where

$ P_c $ and$ \rho_c $ of Eq. (9) represent the radial pressure (5) and energy density, respectively, at the center of the star. At the core of the star, specifically at$ r=0 $ , it is observed that the radial and tangential pressures are equivalent when the conditions$ B_{\rm{eff}} = B_{\rm{eff}}, \perp $ and$ \lambda=\lambda_{\perp} $ are satisfied. This condition indicates that the fluid attains isotropy at the center of the star. Additionally, it is noteworthy that the parameters$ B_{\rm{eff}}, \perp $ and$ \lambda_{\perp} $ contribute to the tangential pressure and are within the same value ranges as$ B_{{\rm{eff}}} $ and λ, respectively. {It is worth noting that in this setup the parameters for the radial and tangential directions, written as λ and$ \lambda_\perp $ , are allowed to differ. This does not imply that the underlying microscopic physics changes with direction; rather, it provides a way to capture how strong interactions, possible phase transitions, or collective stresses might manifest as anisotropic behavior. At the stellar center we impose$ \lambda=\lambda_\perp $ , thereby restoring isotropy, while controlled deviations arise only away from the center. In this sense, the construction is analogous in spirit to other anisotropy models considered in the literature. Still, here it is cast in a more compact and microphysically motivated form, naturally embedded within the gravity’s rainbow framework. In contrast to the commonly used Bowers–Liang [64] or quasi-local models [46], which introduce anisotropy through externally prescribed stress profiles$ \Delta(r) $ , our formulation emerges as a direct extension of the interacting quark matter EoS. This approach naturally permits distinct couplings for radial and tangential pressures, while still ensuring isotropy at the center, thereby providing a consistent way to incorporate strong-interaction corrections. Further, we remove the$ B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp} $ parameter by applying dimensionless rescaling as follows:$ \bar{P}_\perp =\frac{P_\perp}{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}, \; \bar{\lambda}_{\perp}=\frac{\lambda^2_{\perp}}{4B_{{\rm{eff}}}} \; \text{and}\; \bar{B} = \frac{B_{{\rm{eff}}, \perp}}{B_{{\rm{eff}}}}, $

(10) and ultimately, we obtain the pressure in the transverse direction in the following dimensionless form

$ \begin{aligned}[b] \bar{P}_{\perp} =\;& \bar{P}_{c} + \frac{1}{3}(\bar{\rho} - \bar{B}) \\&+ \frac{4\bar{\lambda}_{\perp}}{9\pi^2} \left[-1+ \sqrt{1+ \frac{3\pi^2}{\bar{\lambda}_{\perp}} \left(\bar{\rho}-\frac{\bar{B}}{4}\right)}\right] \\ & -\frac{1}{3}(\bar{\rho}_{c} - \bar{B}) - \frac{4\bar{\lambda}_{\perp}}{9\pi^2} \left[-1+ \sqrt{1+ \frac{3\pi^2}{\bar{\lambda}_{\perp}} \left(\bar{\rho}_{c}-\frac{\bar{B}}{4}\right)}\right]. \end{aligned} $

(11) Here, we proceed to rescale the mass and radius into a dimensionless form,

$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} \bar{m} = m \sqrt{{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}} \; {\rm and}\; \bar{r} = r \sqrt{{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}}. \end{array} $

(12) Here, the parameters are rescaled with respect to the effective bag constant, which sets the natural energy scale of the quark matter system. This rescaling reduces the number of free parameters and allows the EoS to be cast in a compact dimensionless form. It also ensures that the formulation connects smoothly to the standard GR limit in the absence of rainbow corrections, while retaining the effects of strong interactions in a controlled manner. Finally, using (7) and (8), the modified Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff (TOV) equations are [47, 60] (we work in natural units

$ G = \hslash= c = 1 $ )$ M_{\rm{eff}}(r, x)= \int^{r}_{0} \frac{4 \pi r^2 \rho(r)}{\Sigma^{2}(x)} dr \equiv \frac{m(r)}{\Sigma^{2}(x)}, $

(13) $ P' = -(\rho+P_{r})\Phi'+ \frac{2}{r}\left(P_{\bot}-P\right), $

(14) $ \Phi'(r)=\frac{M_{\rm{eff}}(r, x) \Sigma^{2}(x)+4\pi r^3 P}{r\left(r-2M_{\rm{eff}}(r, x) \right)\Sigma^{2}(x)}, $

(15) where prime denotes the derivative with respect to the radial coordinate r. We can also transform it into a dimensionless form by substituting the non-barred symbols with their corresponding barred counterparts. It should be noted that the normal relation

$ (M, R) $ can be recovered by introducing$ (M, R) $ =$ (\bar{M}/ \sqrt{{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}}, \bar{R}/ \sqrt{{4\,B_{{\rm{eff}}}}}) $ , and we present$ M-R $ relations in normalized form. -

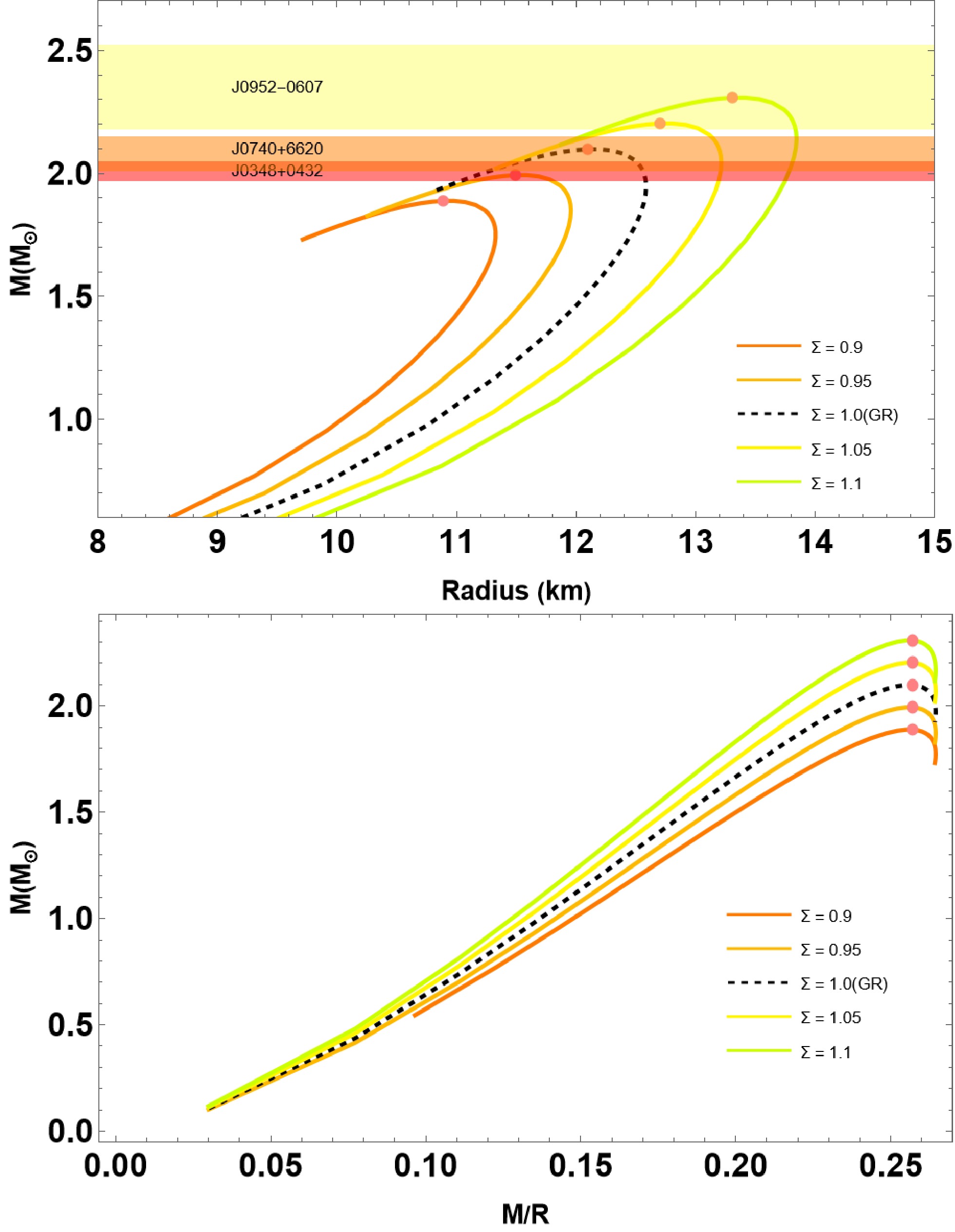

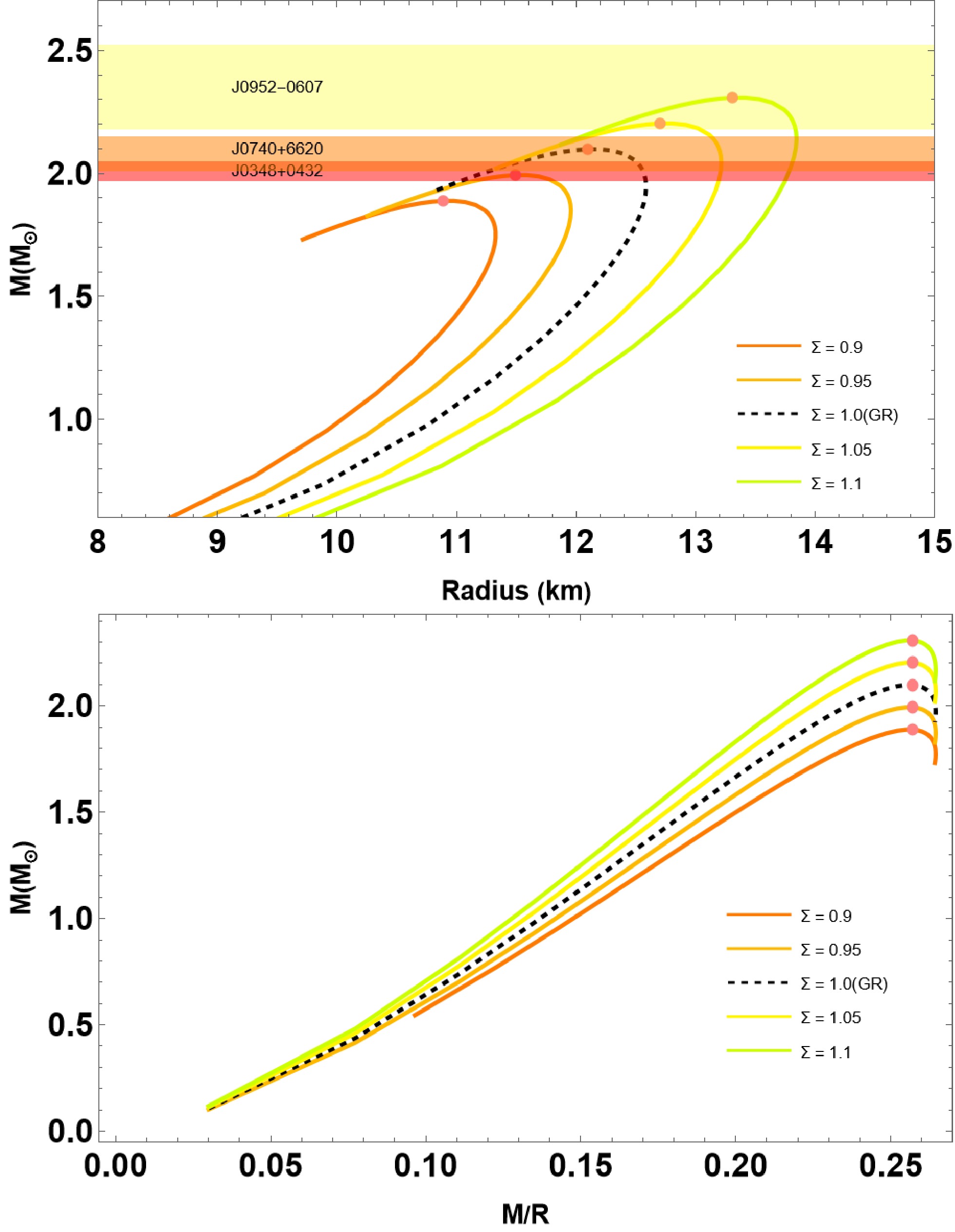

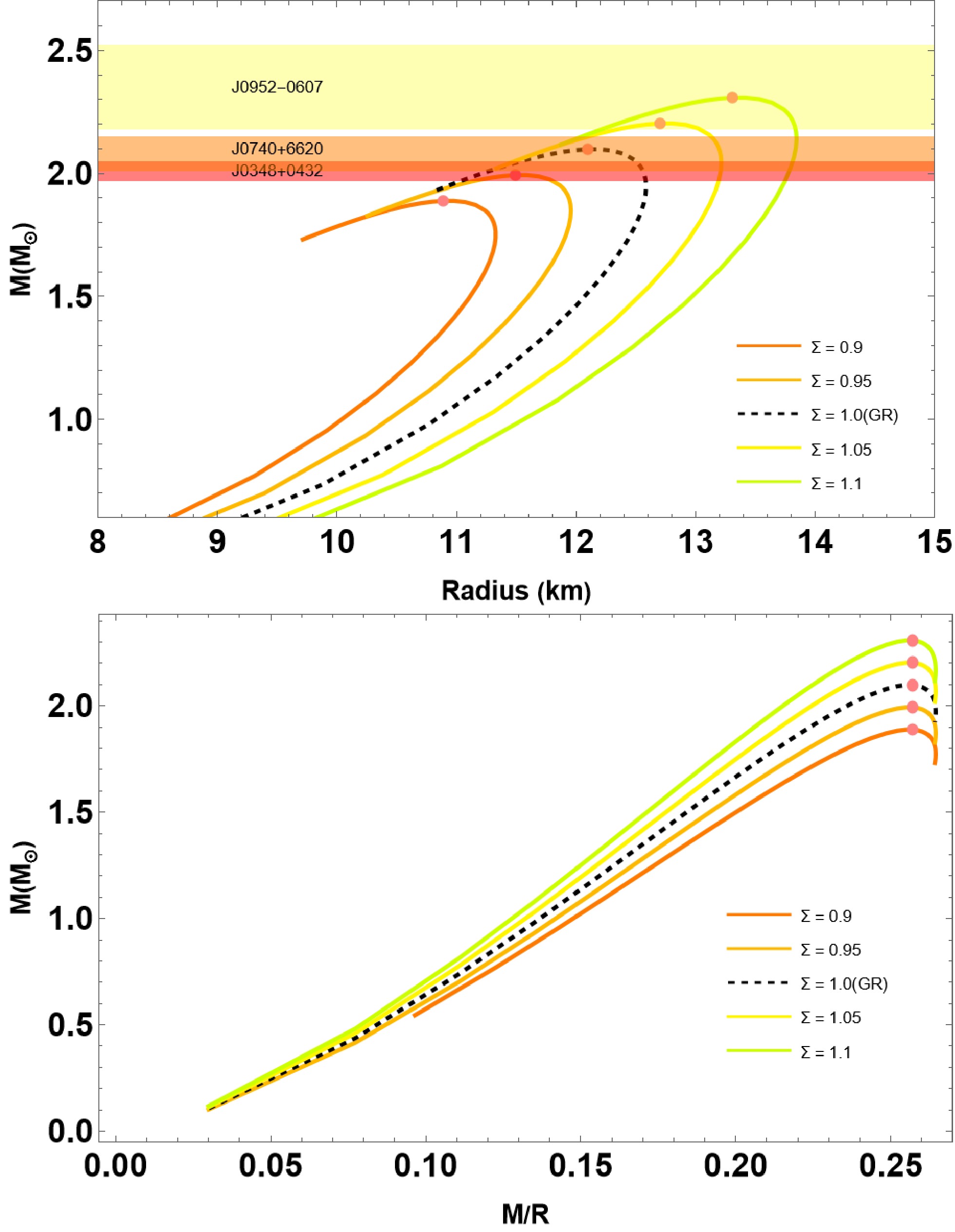

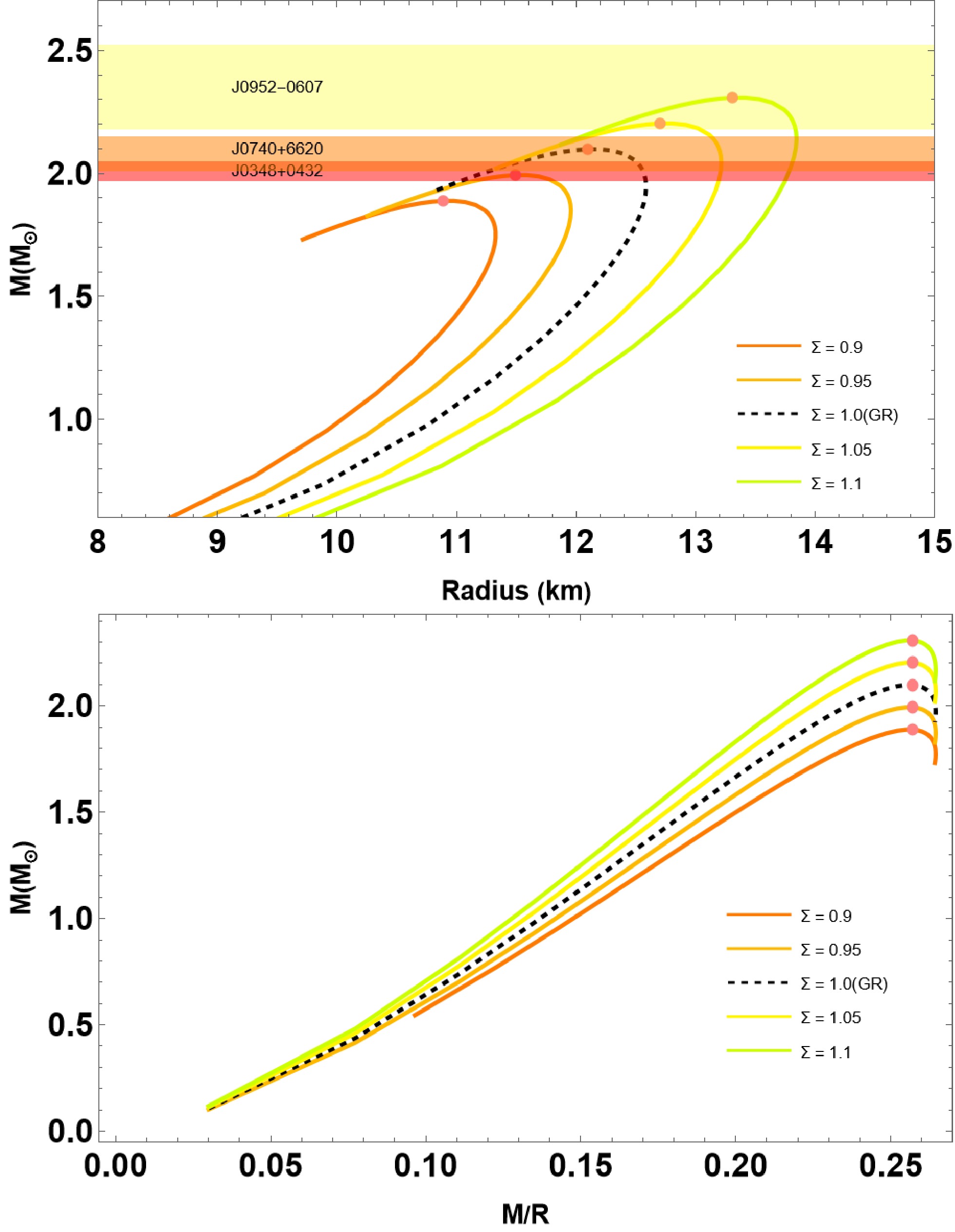

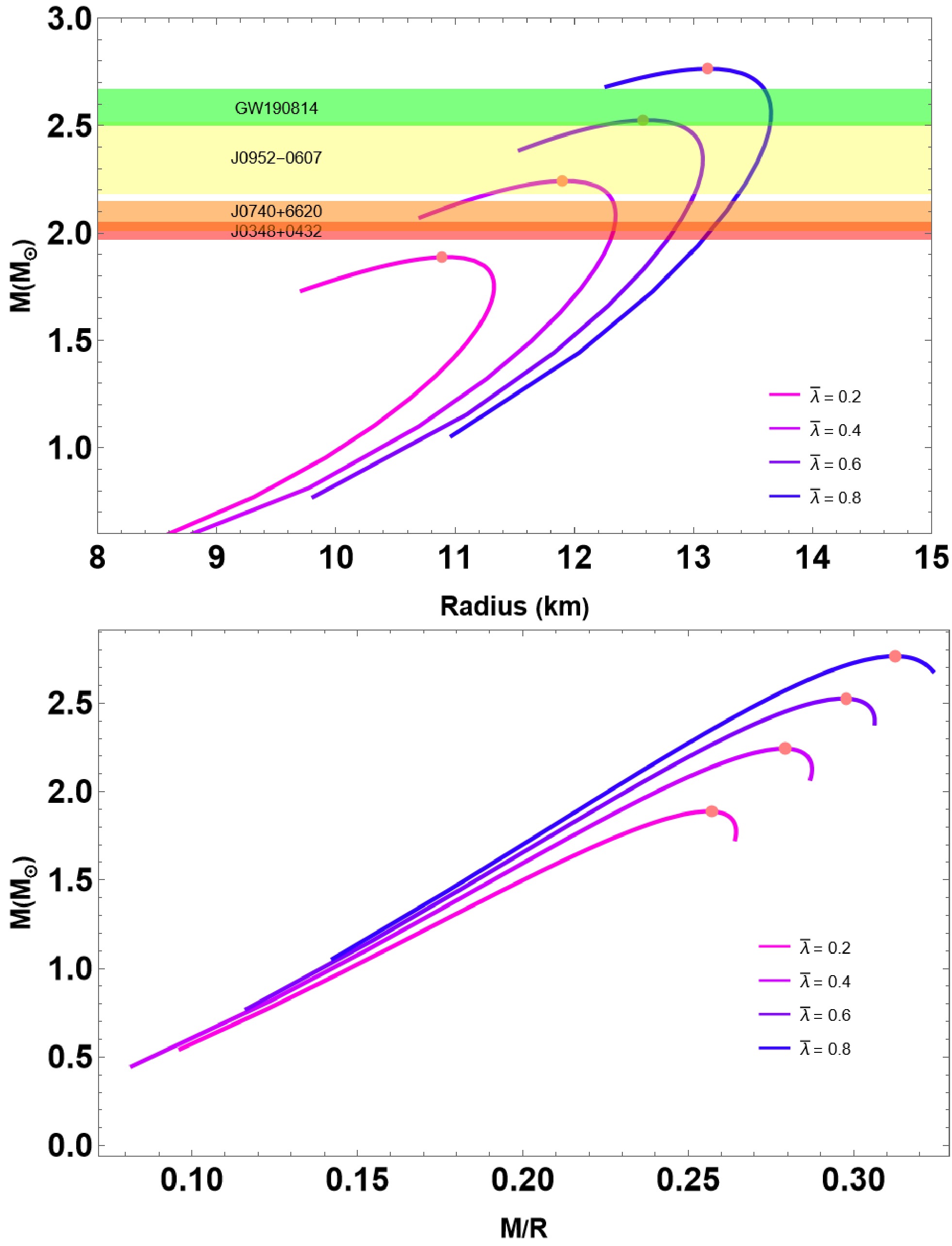

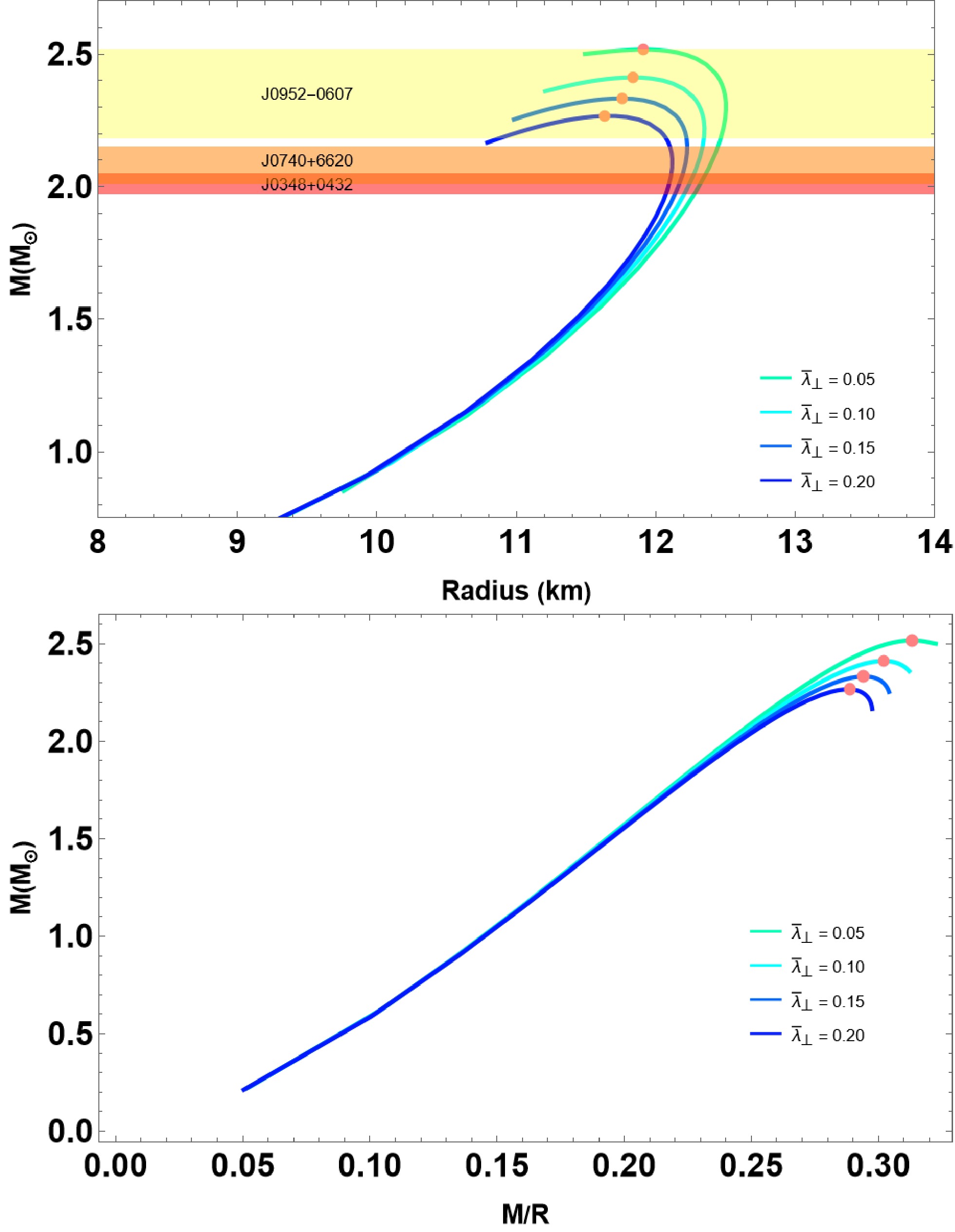

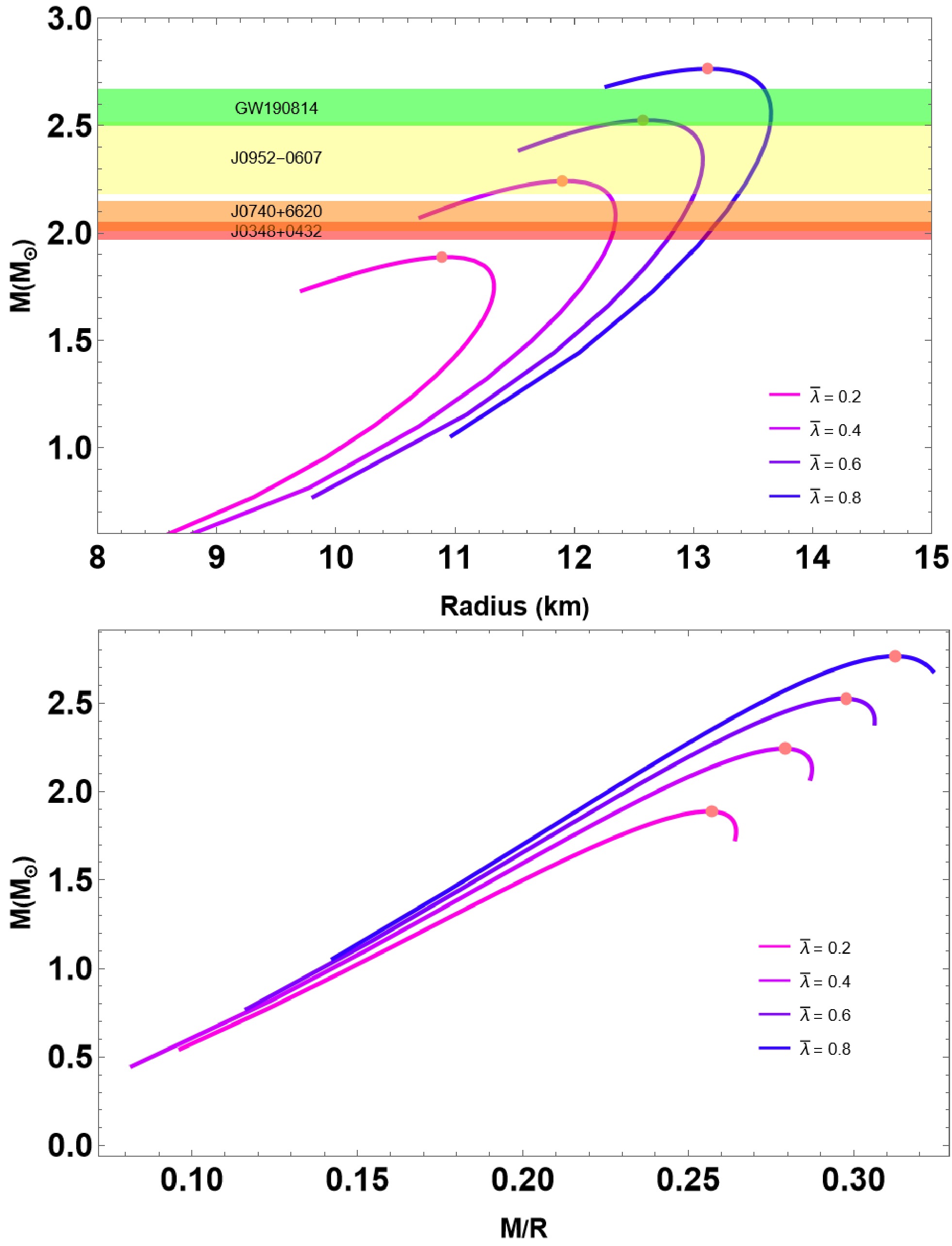

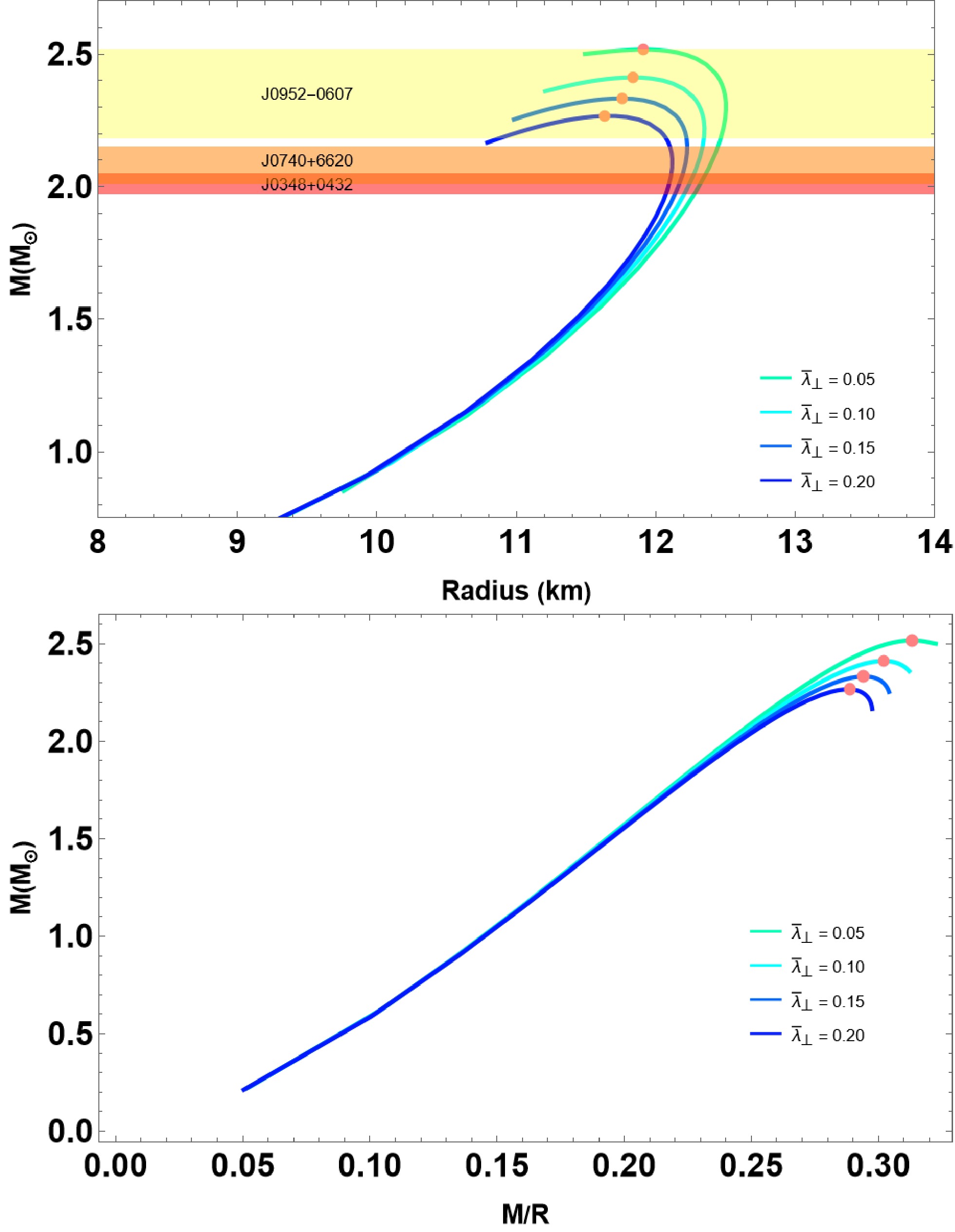

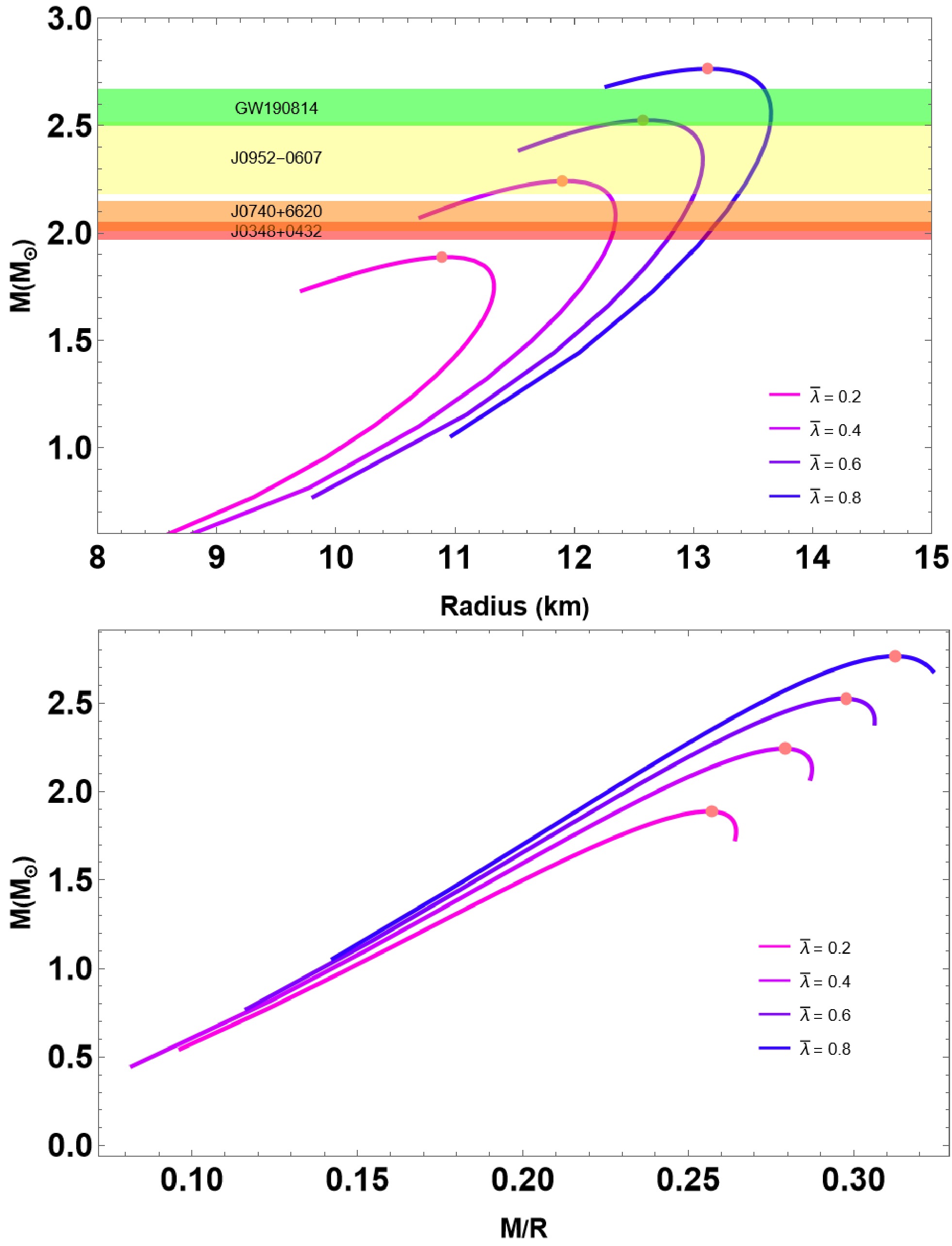

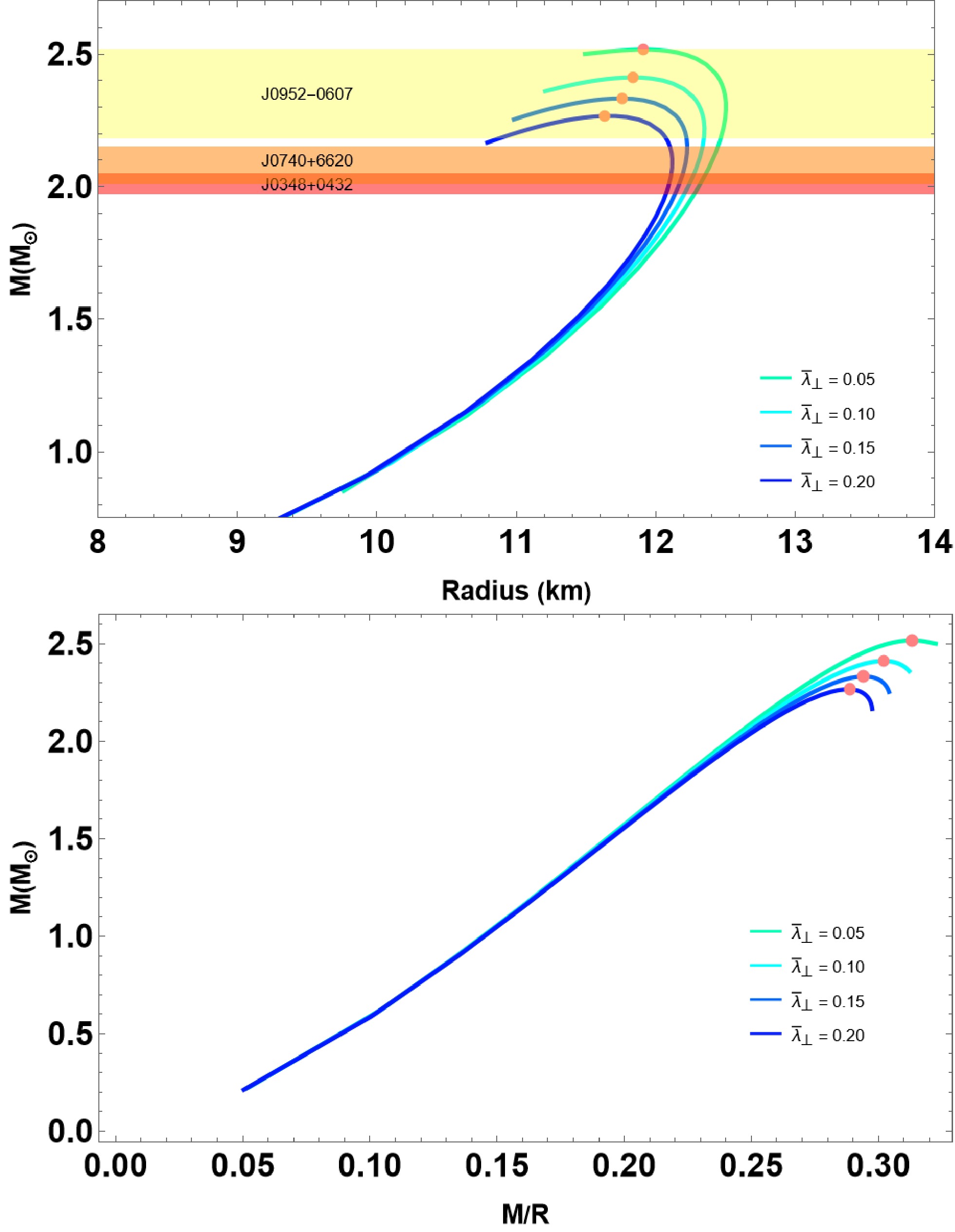

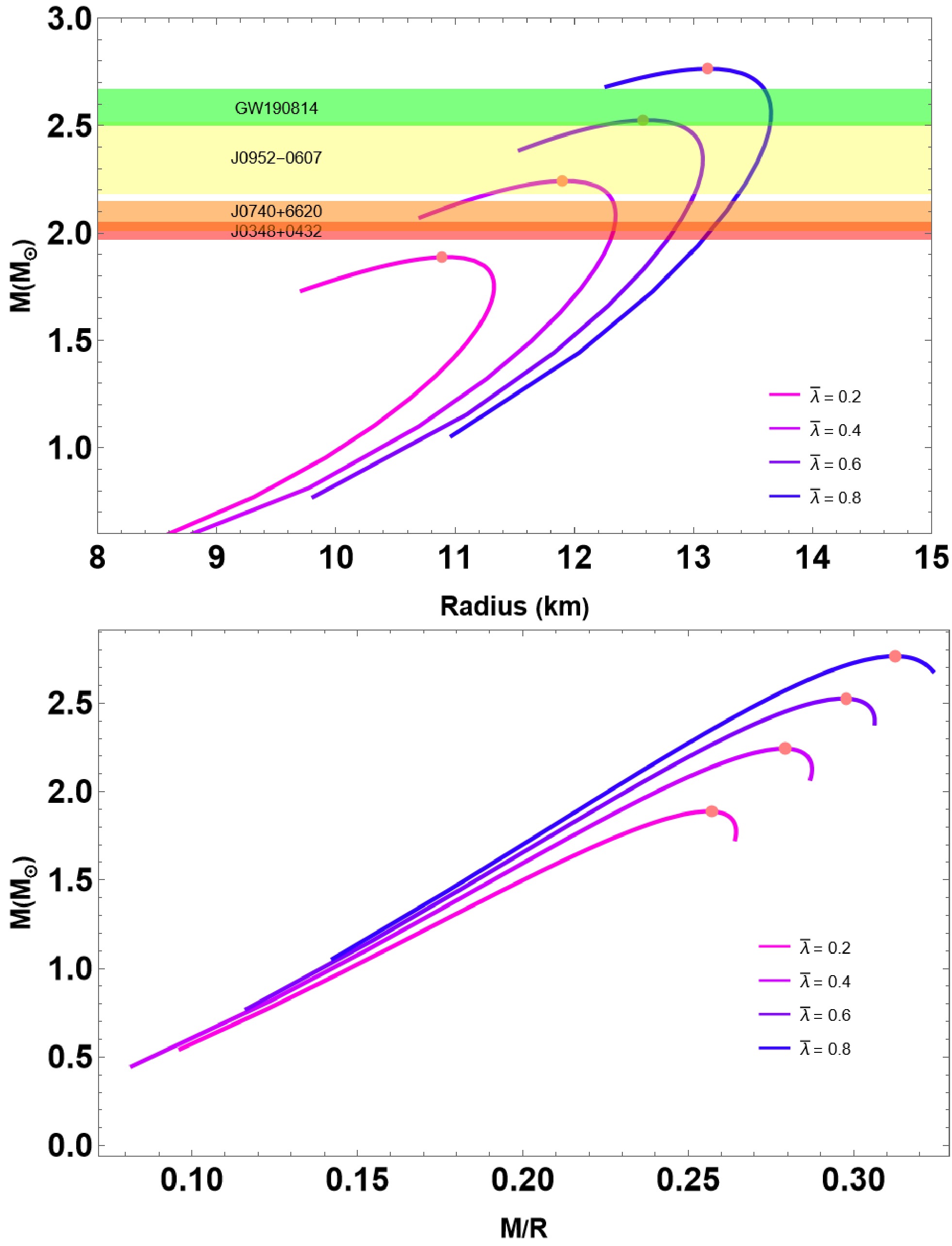

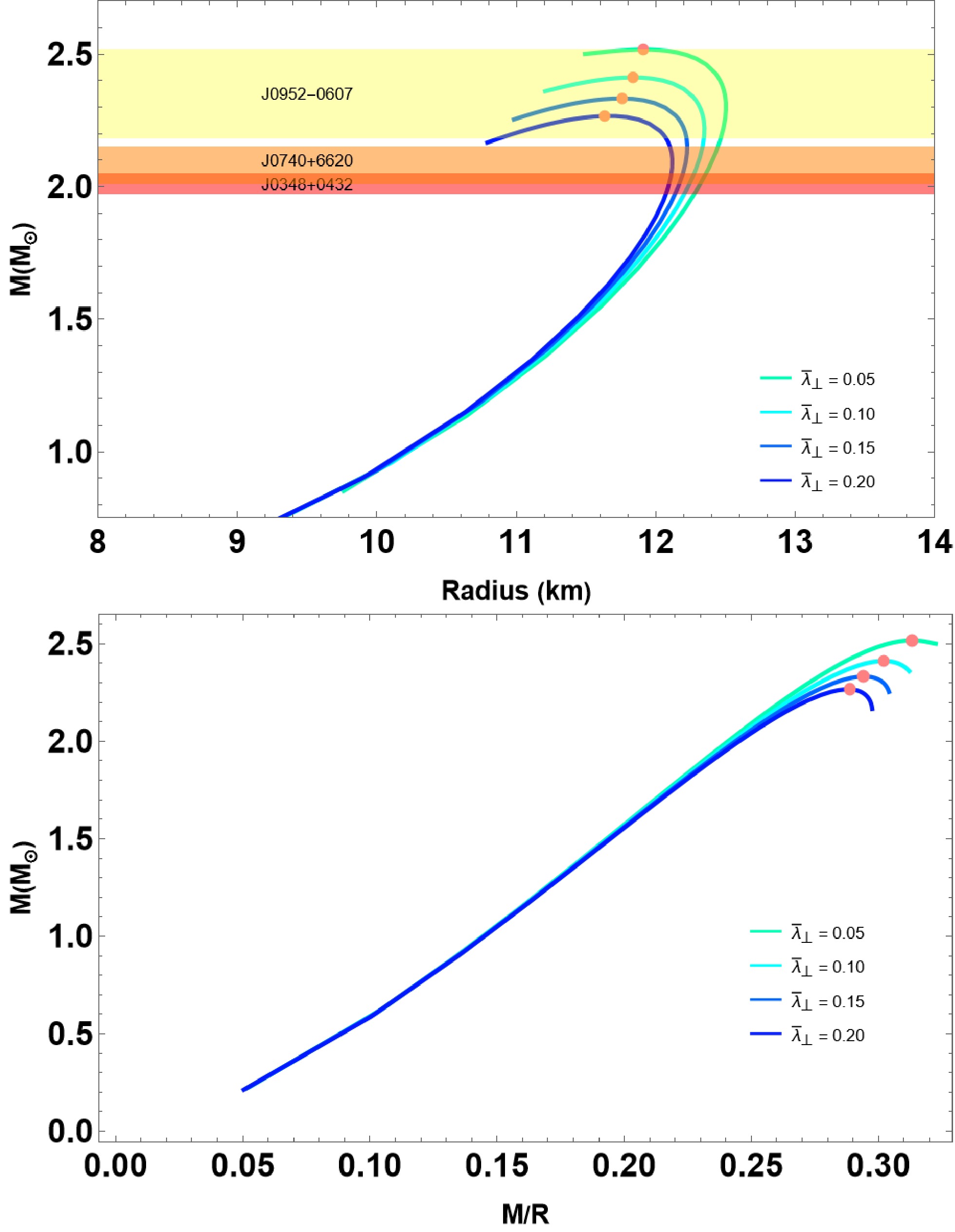

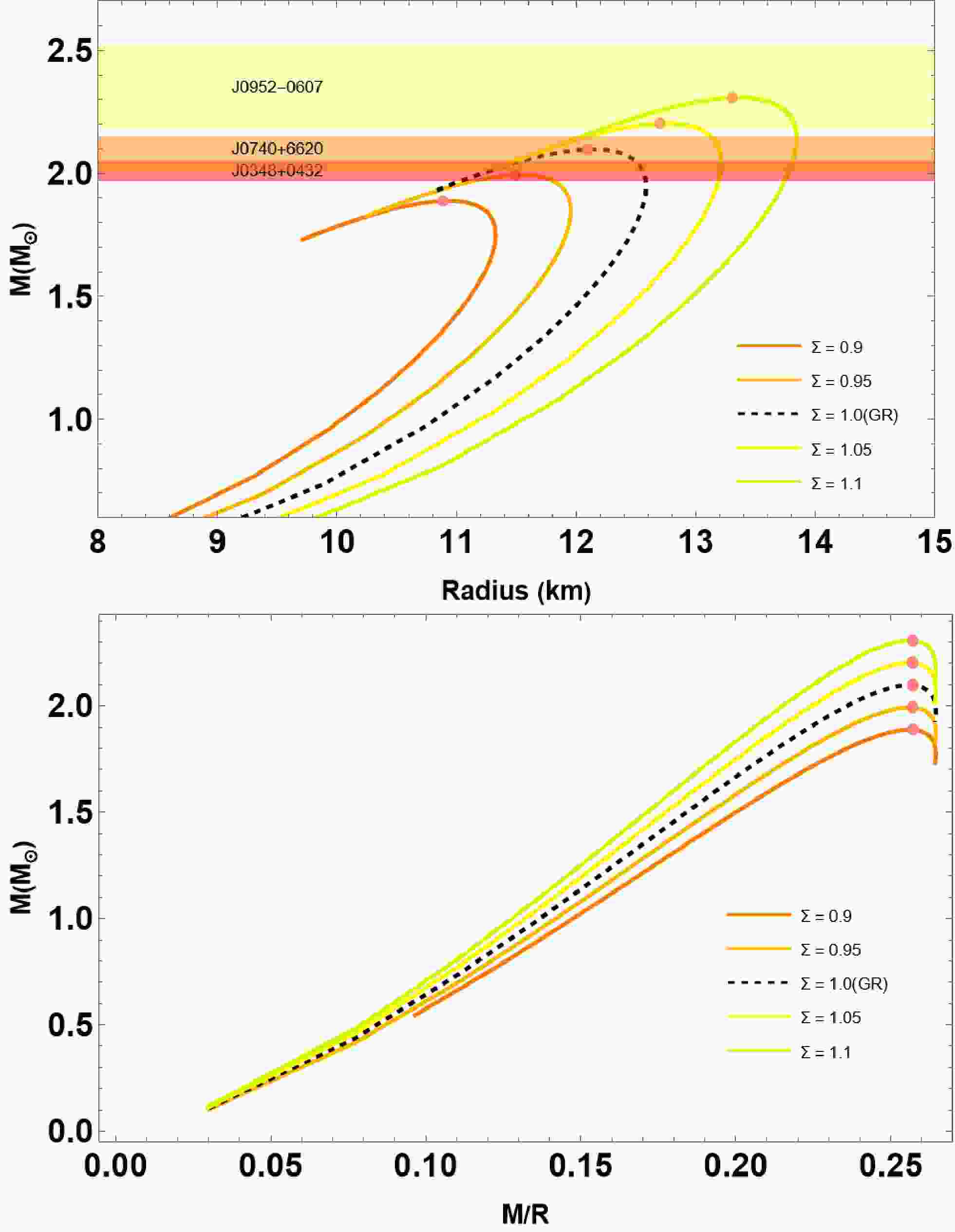

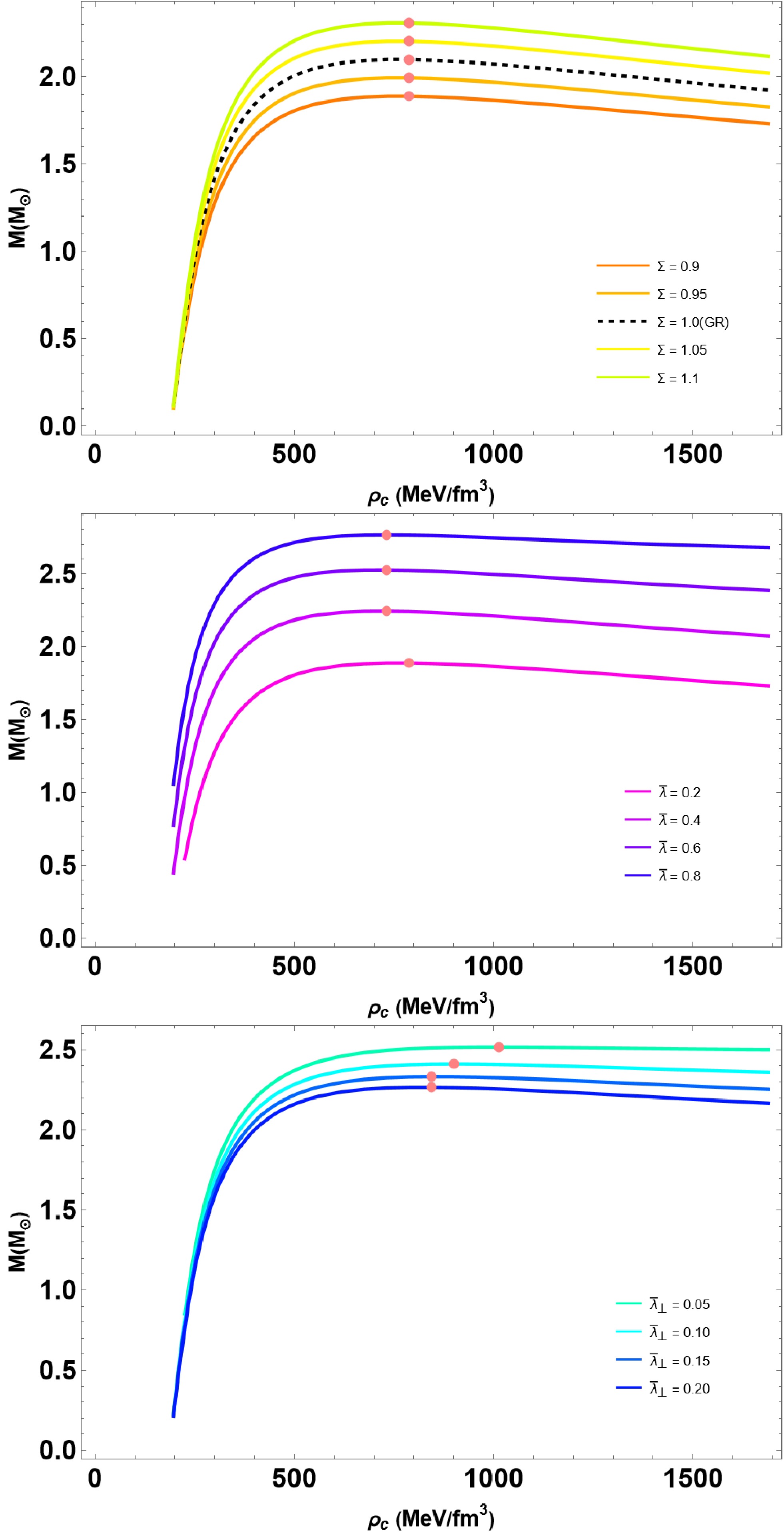

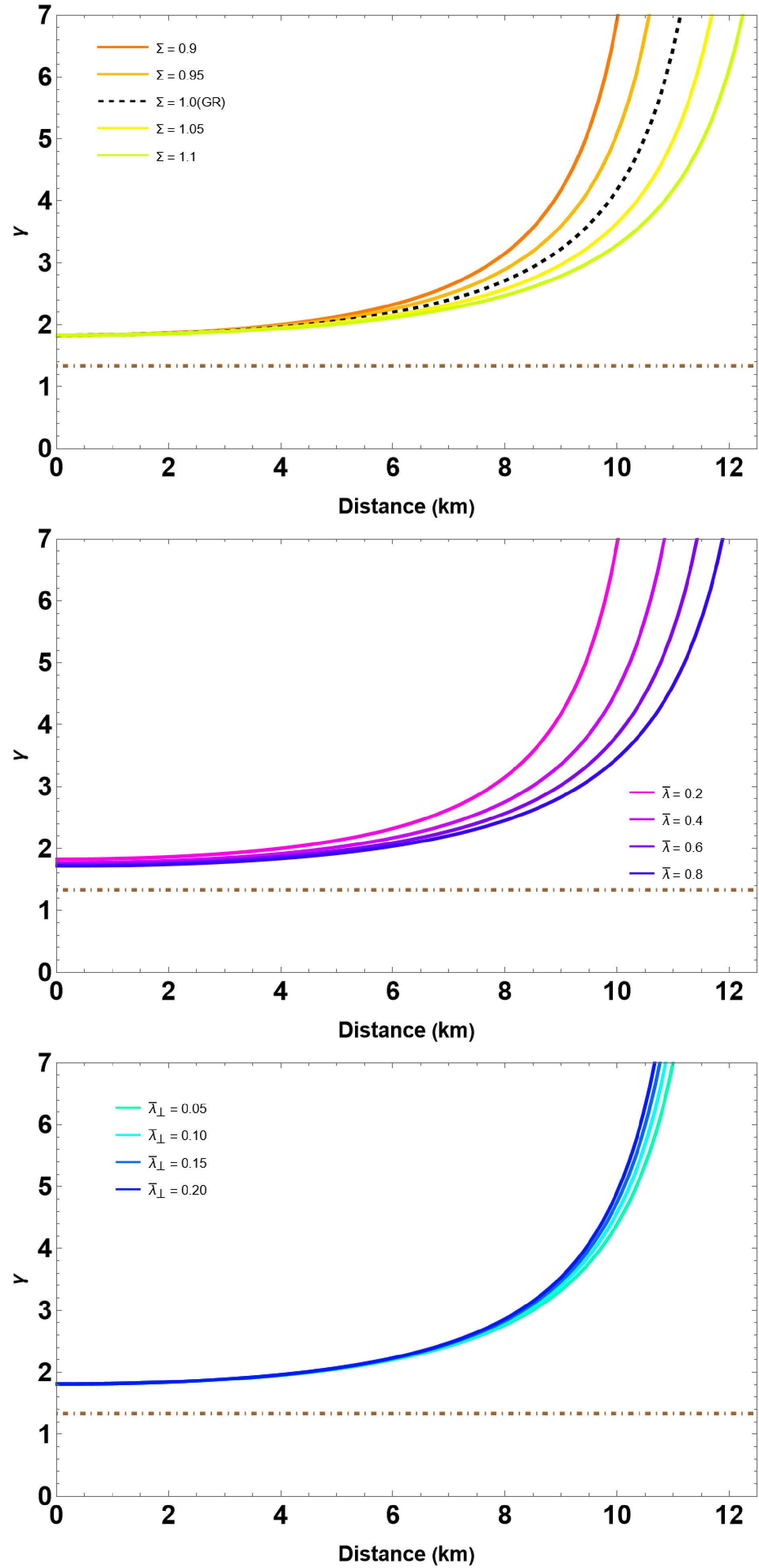

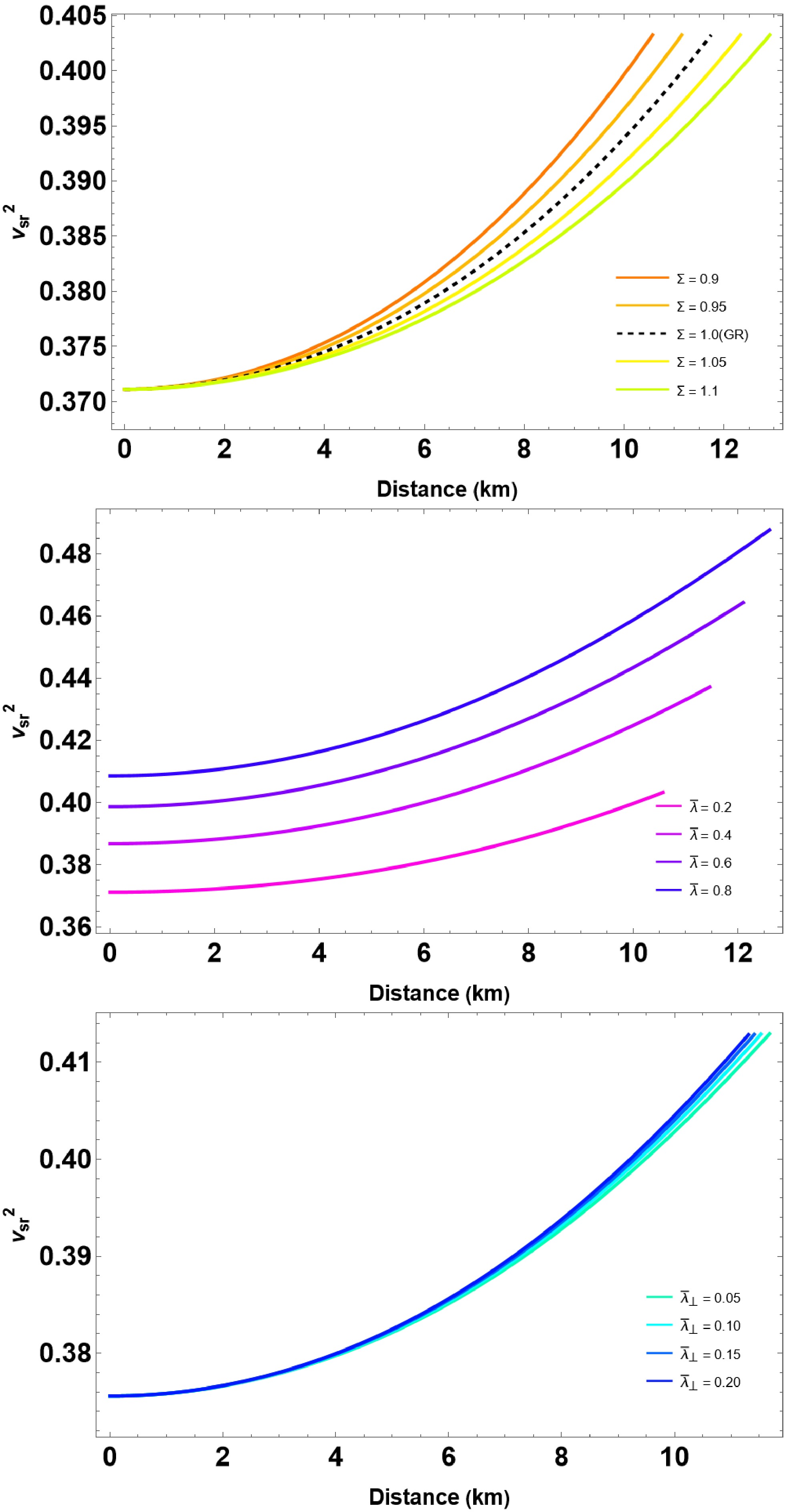

In this section, we outline methods for solving the differential Eqs. (13)−(15) using a fourth-order Runge-Kutta method with adaptive step size control, in conjunction with the specified EOSs (Eqs. (11) and (5)). To achieve this, we need to specify the appropriate boundary conditions and subsequently integrate them, starting at the star's center and extending to a specific radius where the radial pressure equals zero, i.e.,

$ P(R) = 0 $ . The initial conditions are given by$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} \rho(0) = \rho_c, & m(0) = 0, \end{array} $

(16) where

$ \rho_c $ represents the value of the central energy density. Additionally, we need an exterior Schwarzschild solution [66] to match this interior spacetime, given by$ {\rm e}^{2\Phi(R)} = 1-\frac{2M}{R}, $

(17) with

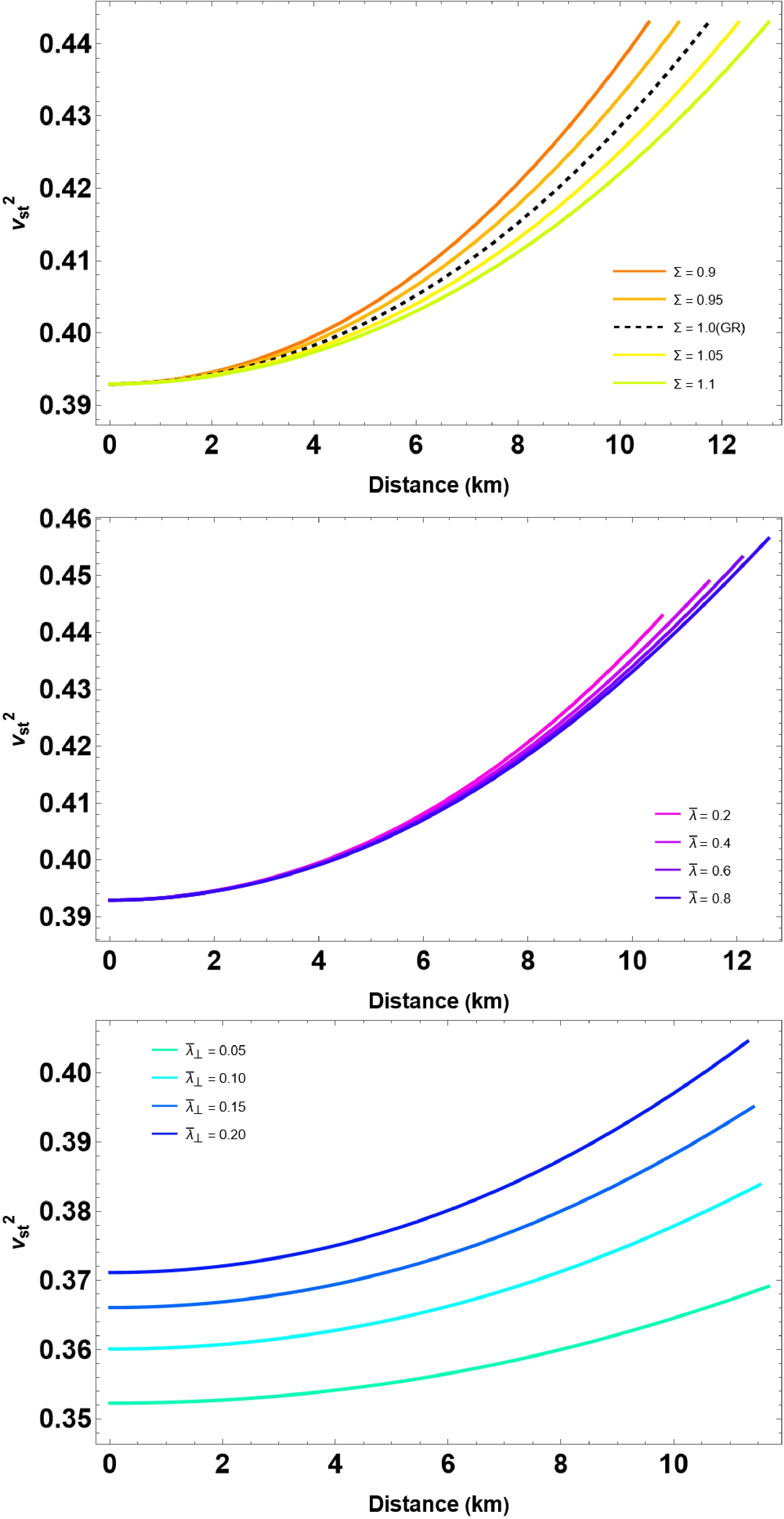

$ M = m(r=R) $ being the total mass of the star. In this study on QSs, we examine the influences of three parameters, specifically, Σ,$ \bar{\lambda} $ , and$ \bar{\lambda}_{\perp} $ . The parameter$ \bar{\lambda} $ characterizes the strength of strong interaction effects in radial pressure by color superconductivity and pQCD corrections. In contrast,$ \bar{\lambda}_\perp $ influences transverse pressure under an anisotropic environment. Both parameters are rescaled with respect to the effective bag constant to represent a dimensionless form of the EoS. The rainbow parameter Σ, which is derived from gravity's rainbow, encodes high-energy modifications to spacetime curvature, influencing the equilibrium structure of compact stars. We adopt a phenomenological choice for Σ within the narrow range$ 0.9 \leq \Sigma \leq 1.1 $ , following earlier studies of gravity's rainbow [59]. This range captures possible Planck-scale modifications to spatial geometry while ensuring smooth recovery of general relativity in the low-energy limit and permitting measurable corrections in the ultra-dense regime of compact stars. Here, we present the relations$ (M-R) $ by choosing the bag constant$ B = B_{\perp}= 70 $ MeV/fm3 and$ \bar{\lambda} $ ,$ \bar{\lambda}_{\perp} $ $ \in [0, 1] $ . Together, these parameters allow us to investigate how strong interactions, anisotropy, and quantum gravity-inspired corrections jointly affect the structure and stability of QSs. -

In this section, we outline methods for solving the differential Eqs. (13)-(15) are solved using a fourth-order Runge-Kutta method with adaptive step size control, in conjunction with the specified equations of state (11) and (5). To achieve this, we need to specify the appropriate boundary conditions and subsequently integrate them, starting at the star's center and extending to a specific radius where the radial pressure equals zero, i.e.,

$ P(R) = 0 $ . The initial conditions are given by$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} \rho(0) &= \rho_c, & m(0) &= 0, \end{array} $

(16) where

$ \rho_c $ represents the value of the central energy density. Additionally, we need an exterior Schwarzschild solution [66] to match this interior spacetime, given by$ e^{2\Phi(R)} = 1-\frac{2M}{R} $

(17) with

$ M = m(r=R) $ being the total mass of the star. In this work on QSs, we examine the impacts of three parameters, specifically, Σ,$ \bar{\lambda} $ , and$ \bar{\lambda}_{\perp} $ . Since, the parameter$ \bar{\lambda} $ characterizes the strength of strong interaction effects in radial pressure by colour superconductivity and pQCD corrections. In contrast,$ \bar{\lambda}_\perp $ is the parameter that influences transverse pressure under an anisotropic environment. Both parameters are rescaled with respect to the effective bag constant to represent a dimensionless form of the EoS. The rainbow parameter Σ, which is derived from gravity's rainbow, encodes high-energy modifications to spacetime curvature, influencing the equilibrium structure of compact stars. We adopt a phenomenological choice for Σ within the narrow range$ 0.9 \leq \Sigma \leq 1.1 $ , following earlier studies of gravity's rainbow [60]. This range captures possible Planck-scale modifications to spatial geometry while ensuring smooth recovery of general relativity in the low-energy limit and permitting measurable corrections in the ultra-dense regime of compact stars. Here, we present the relations$ (M-R) $ by choosing the bag constant$ B = B_{\perp}= 70 $ MeV/fm3 and$ \bar{\lambda} $ ,$ \bar{\lambda}_{\perp} $ $ \in [0, 1] $ . Together, these parameters allow us to investigate how strong interactions, anisotropy, and quantum gravity-inspired corrections jointly affect the structure and stability of QSs. -

In this section, we outline methods for solving the differential Eqs. (13)−(15) using a fourth-order Runge-Kutta method with adaptive step size control, in conjunction with the specified EOSs (Eqs. (11) and (5)). To achieve this, we need to specify the appropriate boundary conditions and subsequently integrate them, starting at the star's center and extending to a specific radius where the radial pressure equals zero, i.e.,

$ P(R) = 0 $ . The initial conditions are given by$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} \rho(0) = \rho_c, & m(0) = 0, \end{array} $

(16) where

$ \rho_c $ represents the value of the central energy density. Additionally, we need an exterior Schwarzschild solution [66] to match this interior spacetime, given by$ {\rm e}^{2\Phi(R)} = 1-\frac{2M}{R}, $

(17) with